What a name! A practical guide to ‘grass’ seed mixtures and other fodder crops in various editions in the 1800s by the Lawsons, Edinburgh seed merchants. Examples of complex grass mixtures, where ‘grass’ included legumes and other broadleaf species. Legumes typically 25% by weight of seed. Sometimes sown with a corn, such as barley, to protect the grass in the first year. Guidance on fodder crops such as sainfoin and whin (gorse). High sown diversity, now mostly gone, but recorded. Latest in the Living Field’s series on crop diversification.

The Living Field’s exploration of crop diversification or re-diversification – growing more things and more different things on the same piece of land – found that some complex species mixtures used in the 1800s and early 1900s had reformed in the Garden’s meadow and surrounding grass [1]. Some species were sown but others just moved in, presumably enticed by the low-nutrient status of the soil and some friendly neighbours.

A century or more ago, grass seed mixtures were varied to suit the intended use. So, for example, those for one crop of hay had fewer species than others for permanent pasture. Yet what is clear from Agrostographia [2] and later works [3] is that quality ‘grass’ seed in the 1700s and 1800s consisted of complex mixtures of grass, legumes and other broadleaf (dicot) plants. On many farms, the forage legumes probably contributed more of the overall nitrogen input by biological fixation than crops such as beans and peas. The legumes also had a higher and different protein content to that of the grass species.

Given present interest in re-diversification, we here explore this practical guide and definitive study of complex ‘grass’ seed mixtures and other fodder crops.

The Lawsons’ Agrostographia

The 1800s was a time of great invention and experimentation. The Improvements of the 1700s had shifted agriculture to a higher trajectory, but there was still a need to improve the ‘grass’ that cows and sheep grazed and were fed. The process of nitrogen fixation by legumes was not scientifically understood, but the experimenters knew that legumes like clovers enriched the soil and gave better yields of livestock when they were present as part of the ‘grass’.

Among the foremost experimenters of the time, from the early 1800s, were the Lawsons, a seed company based in Edinburgh. In addition to their major efforts in trialling and documenting all the arable and horticultural plants that were and could be grown in Scotland [4], they were active in experimenting on ‘grass’ seed mixtures for different purposes.

They worked on trials first in the early 1800s, published their recommendations in 1833, refined them in their 1836 Agriculturalist’s Manual [4], and continued to update them in editions of the treatise named Agrostographia [2], the 6th edition of 1877 being used here. The treatise contains an introduction to grass mixtures, then tables which advise the species and weights of seed that should be sown for different purposes, such as long-term grazing, pasture under orchard trees, conversion of wet land and stabilising soil against coastal erosion.

The refinement and complexity of these seed mixtures was a way forward – a way out of the stagnation of unimproved grazing land.

Complexity for purpose

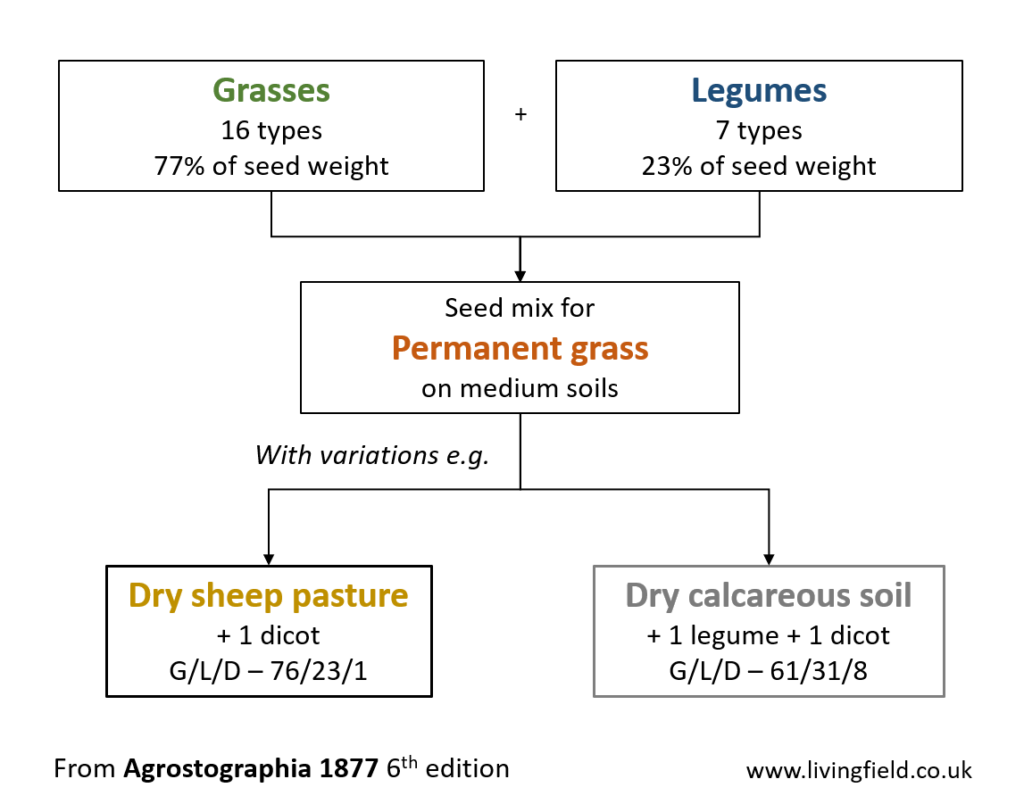

Where the aim was for one to three years hay or pasture, Agrostographia recommends mixtures of 6 – 9 species of grasses and legume, usually those able to form cover quickly. Mixtures for permanent pasture were more complex, selected from 16 types of grass and 7 types of legume (Fig. 1), where ‘types’ were mostly different species but occasionally different varieties of a species. The mixtures were varied slightly to suit three grades of heaviness of the soil and depending on whether the grass seed mixture was sown along with a corn crop, such as barley in spring, to ‘nurse’ the grass mix until it established. The corn was then usually cut along with the grass for a first hay.

Fig. 1 Composition of grass seed derived from 16 grass and 7 legume types (mostly different species) for permanent pasture, the % seed weight in the top two boxes for medium soils with a ‘nurse’ corn crop sown at the same time. Variations below show the grass/legume/dicot (G/L/D) proportions after additional seed was included for specific purposes. From Table III for permanent pasture mix No. 2 in Agrostographia 1877.

Legumes typically made up 20-25% of the standard seed weight in permanent pasture mixes. The proportion of legumes rose to more than 30% both in grass intended for one to three years duration and for permanent pasture in some conditions such as dry calcareous soil, where sainfoin was recommended along with standard legumes (Fig. 1).

The mixes present a marked contrast with most grass fields today, which contain no legumes or at best a sprinkling of white clover.

Species and varieties

Across their various mixtures, the Lawsons tested and gathered seed for about 50 species of grasses, legumes and other dicot plants. They treated each one like a separate crop, whose traits were identified, and which should contribute specific properties to a mix. The mixes achieved a spread of flowering and maturity times and a balance of architecture and feeding quality in the sward [3].

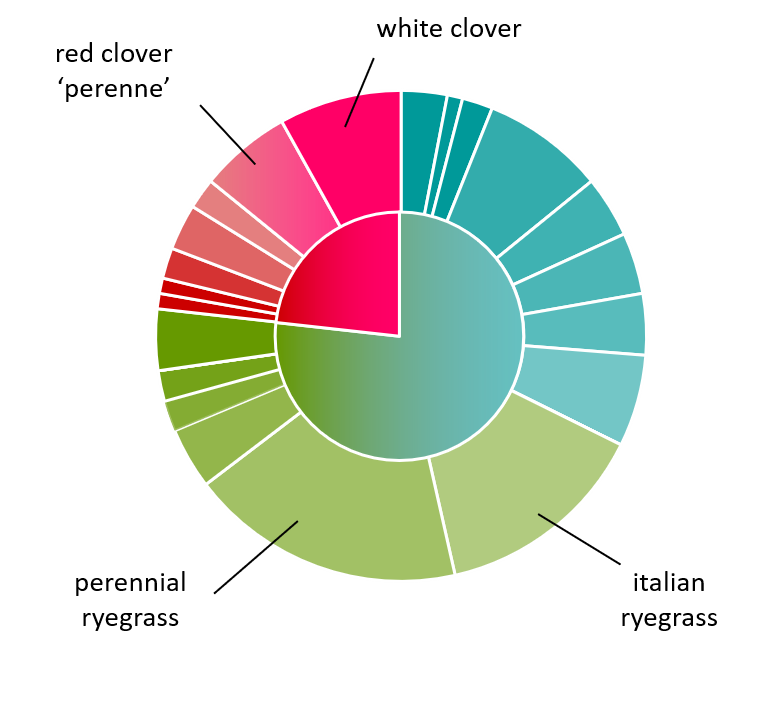

The most abundant grass species in pasture mixes were perennial and italian ryegrass, but others included cock’s-foot, timothy, foxtail and several species each of fescues and meadow grasses. The most abundant legumes were white clover and red clover, the latter often in its perennial form, while others included bird’s-foot trefoils, medics and occasionally sainfoin.

The annular diagram (Fig. 2) shows for a specific mix the proportion of each species or variety in the outer circle in the order given in the manual. Colours and shades of grass from blue to green and legumes from red to pink are to help differentiate the types. The lesser species were each present at between 2% and 6% of the total weight.

Fig. 2 Proportions of species or varieties of grass (blue, green) and legumes (red, pink) in a seed mixture for permanent grass on medium soils assuming sown with a corn crop. From Table III for permanent pasture mix No. 2 in Agrostographia 1877 .

Judging by the many editions and reprints, the Lawsons’ Agrostographia must have influenced many progressive farmers in their attempts to improve hay and grazing. Its contribution was recognised by agriculturalists like Preston, writing in 1887 [5].

‘Artificial’ grasses

The authors distinguish members of the grass family by grouping all legumes and other broadleaf or dicot plants as ‘artificial’ grasses. Among these artificials were typical forage legumes such as lucerne, sainfoin and various tares (e.g. Vicia sativa), which were sometimes grown as a single-species crop, and also plantains, burnets, and yarrow.

Sainfoin and lucerne were at that time commonly grown in the south of Britain, much less in the north. The authors state that the climate of Scotland is too cold for lucerne but sainfoin can be grown in ‘dry’ soils with help in the first year from a nurse corn.

Whin or gorse was another nitrogen-fixing legume recommended as a crop to be cut and pulped for cattle or eaten directly by sheep in the first year or two of growth. Today large areas of rough grazing land are covered by whin, which appears to be rarely eaten by livestock, but Agrostographia recommends growing it from seed in a field as a fodder crop.

How diverse and native were Agrostographia’s mixes

Scotland and indeed much of the UK got all its major crops from other parts of the world. The main cereals came from east of the Mediterranean, potato from across the Atlantic and forest plantation trees, such as sitka spruce, from north America. Even many of our weeds were imported or found their way here.

The position is more complicated for grassland. Traditional, species-rich hay meadows are very rare, around 3% now remaining of those present in Britain before the post-war phase of agricultural expansion. The latest issue of Plant Life magazine points to the botanical richness of the Muker meadows in Yorkshire, for example [6].

Where then do Agrostographia‘s seed mixtures lie on a scale of diversity between such traditional hay meadows and today’s fertilised ryegrass? The combination of more than 20 species takes them far ahead in terms of botanical diversity than nearly all commercial grass fields today. That botanical diversity would have stimulated microbial and invertebrate diversity and hence food for birds and mammals.

They are however less diverse than ancient hay meadows. The mixtures were intended as a crop, a means to increase production measured in the the growth in weight of sheep and cattle per unit area of land. It was before mineral fertiliser was widely used; hence the essential presence of legumes. The capacity of ryegrass for high yield was appreciated. It’s as if the move to ryegrass species, including imported forms, began at this time, well before they came to dominate managed grazing land after the 1950s when mineral fertiliser was routinely applied.

Moreover, Agrostographia’s seed mixes did not consist of just native or local species and varieties. More productive forms of local species were imported and trialled. In describing red clover Trifolium pratense, the authors refer to a common type named English Red Clover, but are aware of a range of other forms named German, Dutch, Flemish, French, American and Normandy. Which of these were use in the various seed mixtures is unclear. Similarly, some improved types of the major grasses were imported from north America.

Agrostographia’s seed mixes are perhaps best viewed as a crop, but one bringing very high in-field biodiversity compared to almost anything else grown at that time.

Lessons for re-diversification

The seed mixes recommended in Agrostographia [2] and related works [3] from the 1800s and early 1900s are a lesson on what can be done to achieve higher production by combining plants having different functional properties. Compared to today’s low-diversity grass they would produce low greenhouse gas emissions, conserve and build soil, and support a rich and active food web.

They could be guides or templates for re-diversification. The mixes could be adapted for different soils and were clearly successful, being used for a large part of the 1800s and later [5]. Several questions remain about them. They probably consisted of imported and native forms. And it is not known whether any of permanent pasture sown in the 1800s remains today – there have been no surveys, and it is even unclear how many fields of permanent grass today contain even one legume. Managed grass is perhaps the most under-surveyed form of agricultural vegetation in Scotland.

The single most valuable lesson from these pioneering works on grassland [2, 3] is that the soils and climate of the country can support complex grass seed mixtures. There is nothing to prevent their revival. Things have changed in the past century but not enough to invalidate their mixtures as starters for trials and experimentation.

Crucial to their adoption in the present time is how they are to be assessed. Rather than being judged on just one output – mass of livestock per unit area – grassland should be judged on a range of other vital criteria including GHG emissions, soil building and support of the food web. If that were the case then complex grass-legume mixtures would win.

Sources, links

[1] For previous Living Field posts on diversification of crops and grass: Diverse grass mixtures in the Living Field meadow and Crop diversification; on a related site, see Grass mix diversity a century past.

[2] Agrostographia; a treatise on the cultivated grasses and other herbage and forage plants. Authors: The Lawson Seed and Nursery Company. Successors to Peter Lawson and Son. Date: 1877 (6th Edition, by David Syme, Manager). Publisher: William Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh and London. Online through sources such as the Biodiversity Heritage Library. [Agrostographia as a title is of much older origin, being that of a major compendium on grasses written in Latin, by or edited by, Johannes Scheuchzer (1684-1738), published 1719, edition of 1775 viewed. Did the Lawsons borrow the name ?]

[3] Other examples of seed mixtures used in the 1800s and early 1900s are given books and manuals by authors H Stephens (1841), RH Elliott (1898, 1908), and WM Findlay 1925. Full details and links on the curvedflatlands site at Grass mix diversity a century past.

[4] Peter Lawson and Son’s main other works are the Agriculturist’s Manual (1836) and the more comprehensive Synopsis of the Vegetable Products of Scotland (1852), available online for download, details and links on this site at Bere in Lawson’s synopsis.

[5] Preston, Samuel P. 1887. Pasture grasses and forage plants, and their seeds, weeds and parasites. Publisher: TC Jack, Ludgate Hill, London. Available online for download.

[6] McCarthy, M. 2020. Fields of gold. Plant Life 86, 28-29 (Spring 2020) – on the Muker meadows in Yorkshire.

[Last edited: 28 April 2020 with minor amendments]