Length of day and solar income around the winter solstice. The significance of Maeshowe on Orkney. Importance of the annual temperature lag for farming. The Turning of the Year in the singing tradition.

From the earliest settlements on these islands, the Winter Solstice has been marked and celebrated as the Turning of the Year. Days will now get longer and the sun rise higher in the sky.

A previous Living Field article on the Winter Solstice gave some explanation of the yearly cycle, the changes in sunrise, sunset, and the various twilights’ at this time of year [1]. The shortest day, usually 21 December, does not coincide with the earliest sunset or latest sunrise. The earliest sunset was about a week ago, but the latest sunrise will not happen for another week. Once that’s passed, the days will lengthen more quickly.

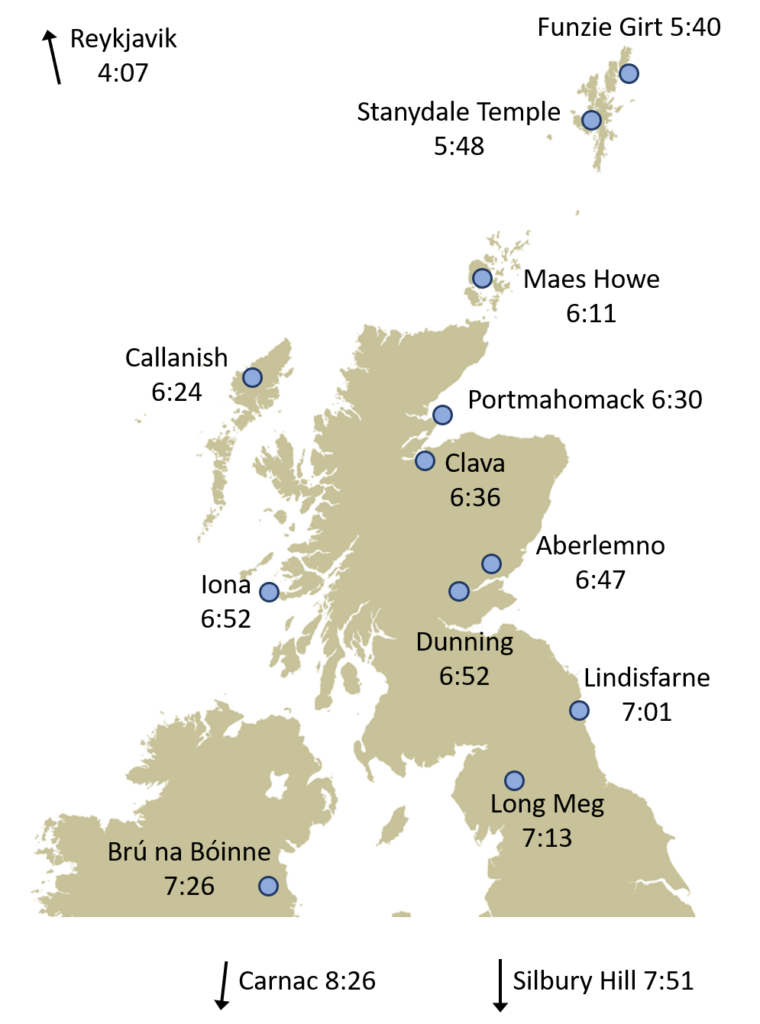

Fig. 1 Daylength at the winter solstice, 21 December, at a range of archaeological and historical sites. Hours:minutes shown are from sunrise and sunset tables for 2020, excluding twilight. First published at Through the solstice on 28 December 2020.

The map of daylength at the solstice (Fig. 1) shows the great decrease from south to north that early farmers had to reckon with when building their cairns, stone circles and alignments. Daylength is eight and a half hours at Carnac, near the Golfe du Morbihan in Brittany, but only five and three-quarter hours in the north of Shetland.

There was compensation in summer when daylength in the north was much longer than in the south. Provided they could get through the winter, our neolithic ancestors had much more time in summer to tend their crops and livestock.

Maeshowe Orkney

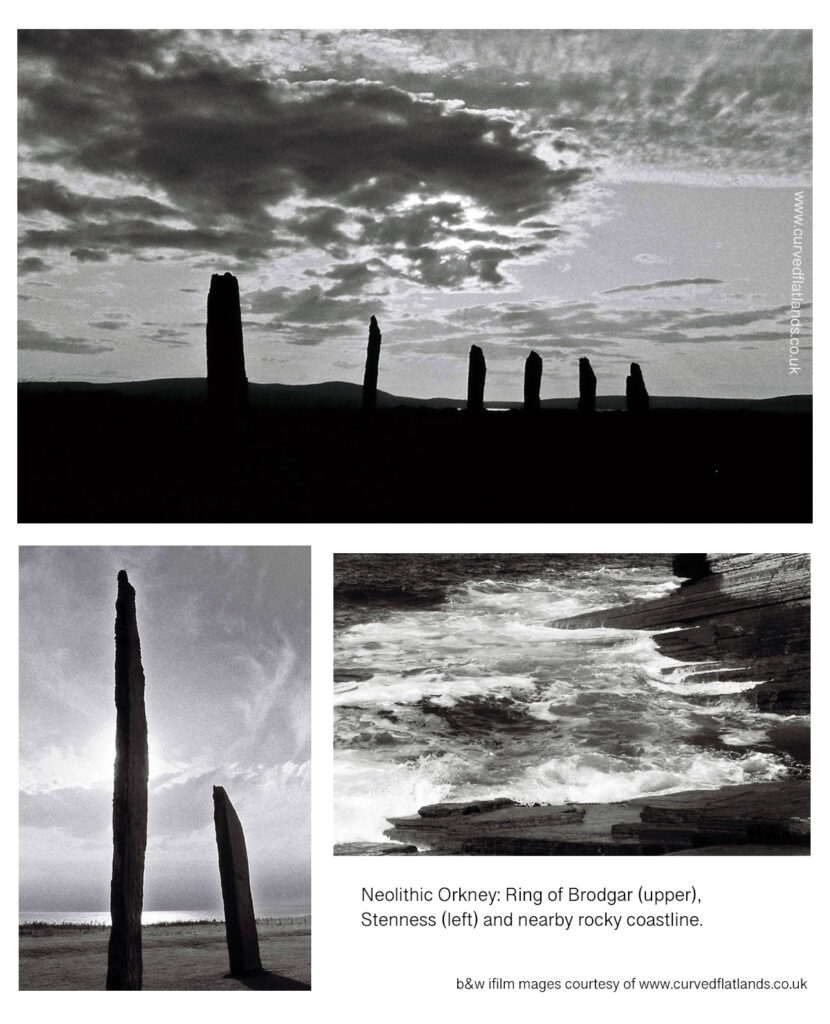

The Maeshowe mound or chambered cairn, built on Orkney 5000 or so years ago, is one of the neolithic monuments aligned with the solar cycle. For several days either side the solstice the setting sun shines down the passage and on to the back wall. Maeshowe is part of the magnificent set of standing stones and settlements at the heart of Neolithic Orkney, close to the Ring of Brodgar and Stenness.

On the afternoon of Winter Solstice 2021, Historic Environment Scotland broadcast a short film about Maeshowe, introduced by ranger Susan Miller and including people describing its construction and purpose, the runes incised on the stone much later, local folk tales and poems in Orkney dialect. Much of the film was recorded inside the chamber. It can be viewed via the HES web site [2].

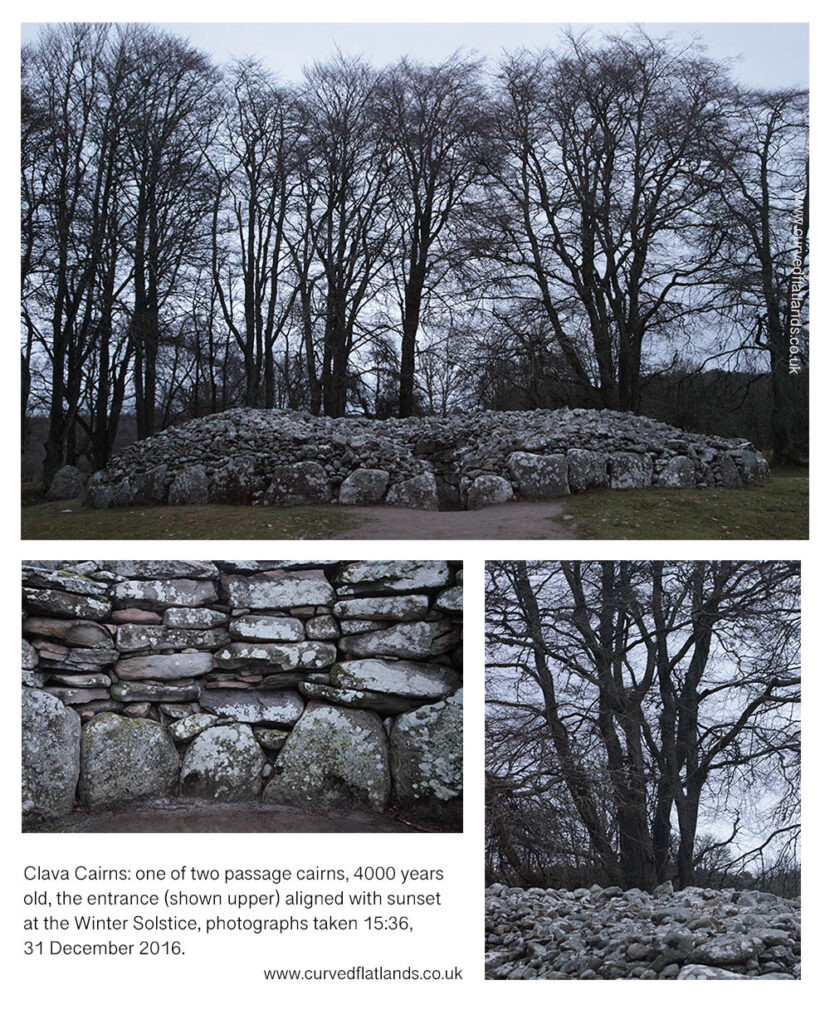

Several other neolithic sites are aligned with sunrise or sunset at the winter solstice. Newgrange at Bru na Boinne in Ireland is one of the most famous [3]. At sunrise, light shines through a ‘roof-box’ above the main entrance stones. The cairns at Balnuaran of Clava near Inverness are also aligned with the winter solstice but at sunset rather than sunrise.

Solar income and the temperature lag

The increasing daylength and twilight may give more time for people to travel and work outside without artificial light, but the plants on which people and their livestock depend are waiting for change in two climatic factors – a rise in temperature enough to encourage seed germination and leaf expansion, and a rise in solar income that the new leaf can use to take in carbon dioxide from the air and grow. The trouble is that the rise in temperature happens one to two months after the rise in solar and that can cause big problems for farming.

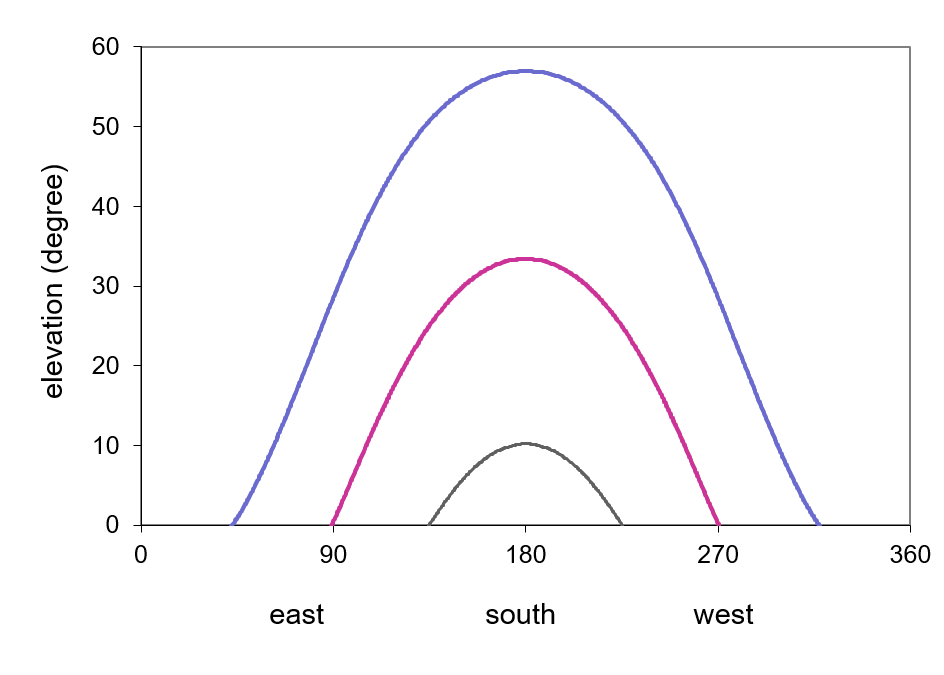

The diagram in Fig. 2 shows the compass direction of sunrise and sunset (the points where each curve rises from and falls to the horizontal axis) and the daily rise and fall of solar elevation in between. The elevation defines the maximum intensity of solar radiation as the sun rises and falls, so the area under a curve represents the total solar income received on a clear day. That received at the winter solstice is also reduced in most years because of cloud.

Fig. 2 Diagram to show the changes through the year in the rising and setting of the sun and its elevation or altitude at latitude 56N (between Aberlemno and Dunning on Fig. 1). The horizontal axis shows the direction of the sun (at 180 degrees it would shine from the exact south), the vertical axis the elevation or altitude of the sun (90 degrees would be directly overhead). The lower curve is for the winter solstice, the upper for the the summer solstice and the middle for the equinoxes. First published at Through the solstice on 28 December 2020.

By the spring equinox on 21 March (the middle curve in Fig, 2) the solar curve has greatly increased: for instance, the elevation at midday is more than half that to come at the summer solstice. There is plenty of solar radiation at this time to support the growth of plants. But look at the agricultural calendar – and spring crops are just being sown, winter crops have hardly recovered from the preceding cold and much livestock farming still relies on last year’s grass, hay and silage. There is little new growth because the temperature is still too low. In consequence, most of the solar income between winter solstice and spring equinox is ‘wasted’ as far agriculture is concerned.

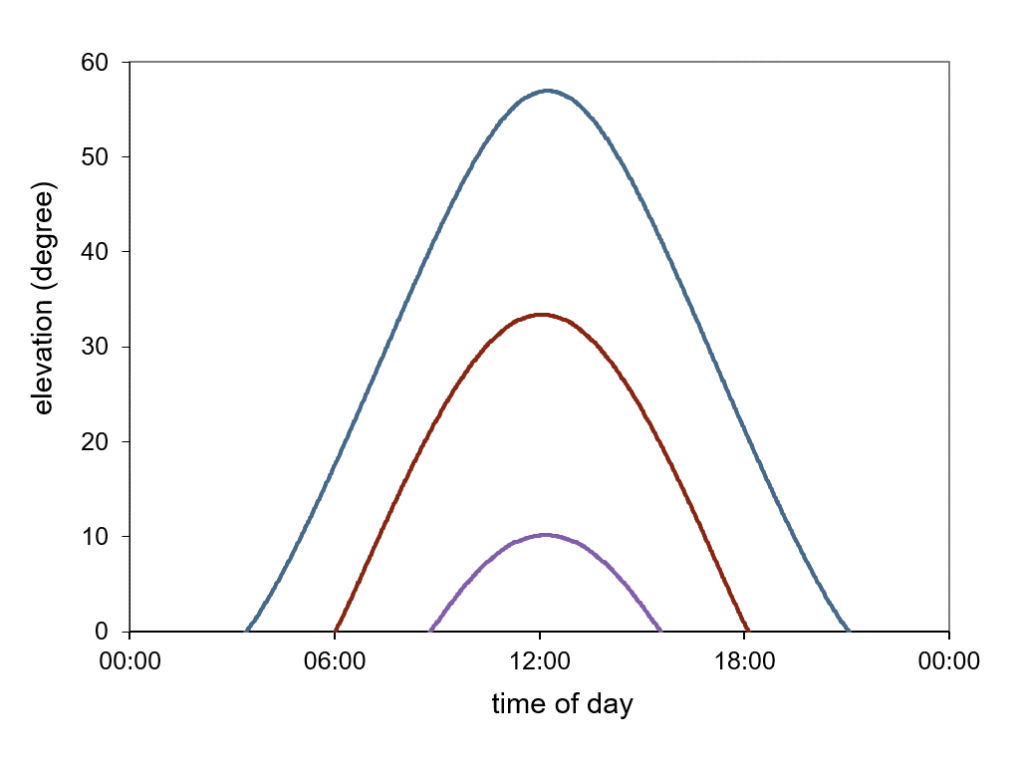

Fig. 3 Annual curves of daily incoming solar radiation (solid line) and daily average air temperature (dashed line) at latitude 56N, showing the curve for temperature lagging behind that of solar by about six weeks [4].

The lag in the annual cycle of temperature, illustrated by the curves in Fig. 3, is typically between one and two months, but is highly unpredictable. Although the rise in solar drives the rise in temperature, the two are only partly coupled, because at any point in the solar curve, change in weather patterns across the north Atlantic can bring in colder, warmer, drier or wetter air.

If the curves for solar radiation and temperature behave themselves, then good management can achieve very high yields of crops and grass. But if the year or the farming gets it wrong, there can be crop failure, and in the past, hunger and sometimes famine. The two to three months after the winter solstice are crucial therefore. This is one reason why so much of the singing Tradition deals with The Turning.

Winter song

Solstice time meant a lot to those who relied on the land and the weather. A couple of hours after the broadcast from Maeshowe [2] on 21 December, the Yorkshire-based Melrose Quartet performed their seasonal songs and tunes online via Live to Your Living Room [5]. They included some of the traditional folk carols are still sung in Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire (and other places). Some originated hundreds of years ago. Their popularity hasn’t died. The tradition is thriving.

Many performances of traditional carols are available online [5]. They Melrose Quartet also sang songs that were crafted more recently and in ways so close to the spirit of tradition that they have become part of it. Here’s an extract from the Sheffield Wassail by Pete Smith: “God bless the old and weary | whose time is nearly run | and all the unsung careers | who are paid a paltry sum’.

The ‘Turning of the Year’ is celebrated in tradition and song throughout Britain [5, 6]. The Living Field’s Winter solstice page in The Year gives some examples and links. The compendium of song named Midwinter – A celebration off the folk music and traditions of Christmas and the Turning of the Year – with text by Nigel Schofield and produced by Free Reed, remains one of the most comprehensive surveys of midwinter traditions in the British Isles.

And finally, a reminder that the season meant death and life to those that tilled the land. Snow Falls by John Tams begins: ‘Cruel winter cuts through like the reaper | The old year lies withered and slain | Like barleycorn who rose from the grave | The new year will rise up again. Then the chorus: And the snow falls | And the wind calls | And the year turns round again.”

So here’s to Christmas and all the Midwinter celebrations, astronomical, vocal, whatever.

Sources | links

[1] The article Through the solstice, containing a description of change in daylength, twilight and solar income was published on this site on 28 December 2020 and gives methods and sources of data used in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

[2] Maeshowe on Solstice day 2021: Historic Environment Scotland’s New online film celebrating the winter solstice on Orkney. See also the entries for Maeshowe at Orkneyjar and Canmore.

[3] Newgrange, Bru na Boinne. For the history of excavation and some early photographs: (a) newgrange.com; (b) the Fr. Michael O’Flanagan History and Heritage Centre; (c) The stones of time by Martin Brennan (1994, Inner Traditions).

[4] The curves in Fig. 3 are central to understanding the effect of weather and climate on agriculture here, and need to be accounted for when predicting the effects of change in climate. The original curves are presented in a recent James Hutton Institute research paper in the journal Plants published 2021.

[5] Folk carols and other winter songs: search Yorkshire / Sheffield / Derbyshire carols for various live videos. For records and books: (a) Broadcast live on solstice day 21 December 2021 via Live to your Living Room, a gig by the folk group Melrose Quartet, based in Sheffield: their CD containing carols and songs, The Rudolf Variations, can be bought at their online store. (b) The Mainly Norfolk web site lists a range of carol albums, e.g. A People’s Carol, On this delightful Morn, Hark, Hark! What news, and many others, mainly from Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. (c) The web site Village Carols gives Links to carol traditions in various parts of the UK and under the Publications tab lists books and recordings, including The Sheffield Book of Village Carols by Ian Russell (2008, Elphinstone Institute Aberdeen University). Also Winter Solstice at the Year on this site.

[6] Scotland has its share of winter traditions. Local is best! Newburgh, a village in Fife, holds its unique Oddfellows Parade on 31 December, cancelled this year (but see photosbyzoe) and is acclaimed for its Wonky Christmas Lights (BBC news item). See also Stonehaven Fireballs at midnight on 31 December and the Up Helly Aa in Shetland later in January.