A note to the Living Field’s exploration of The Year. The Labours in Medieval art and craft. Labours in the remaining Easby church murals, Yorkshire, ca 1250. Adam and Eve in the tradition: delving and spanning. The reformer John Ball. Modern Labours and the Crow.

The ‘Labours of the months’ was an artistic theme that recurred in cathedrals and churches across Europe in the middle ages, typically 1200-1400 AD or 800-600 years ago [1]. The Labours, depicting rural activities through the year, were sometimes paired with the signs of the zodiac. They were crafted in stone, wood and stained glass and occasionally in wall paintings (murals). The great cathedrals of France and Italy display many fine examples.

The Labours had a role in reinforcing power and privilege. In the Très Riches Heures for example [2] the paintings show well turned out peasants about their seasonal activities, but overlooked and dominated by great palaces and castles. And not all the Labours were about the agricultural year: hunting with hawk and dog would also have been the preserve of the wealthy.

So now to Yorkshire …

The Easby Murals

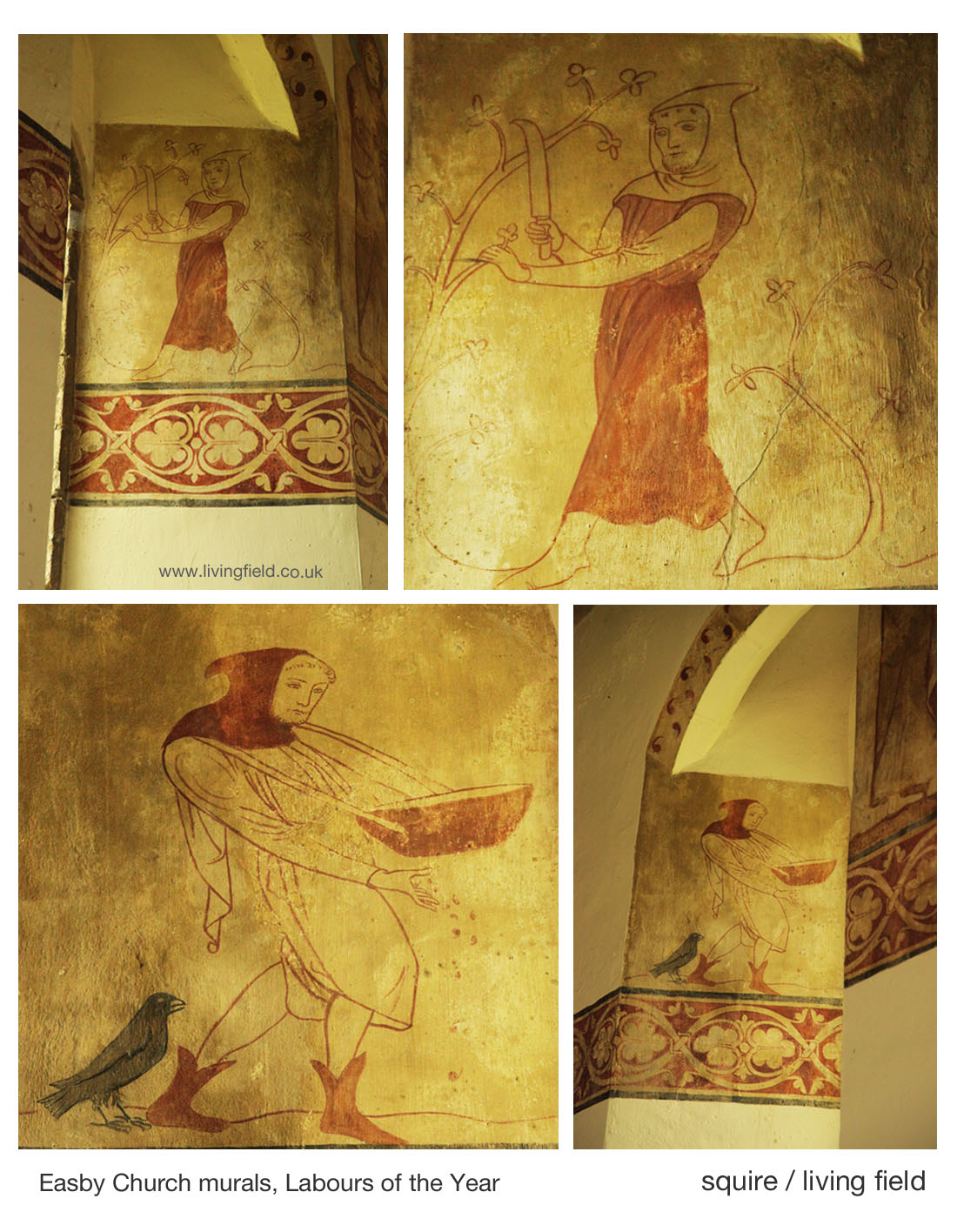

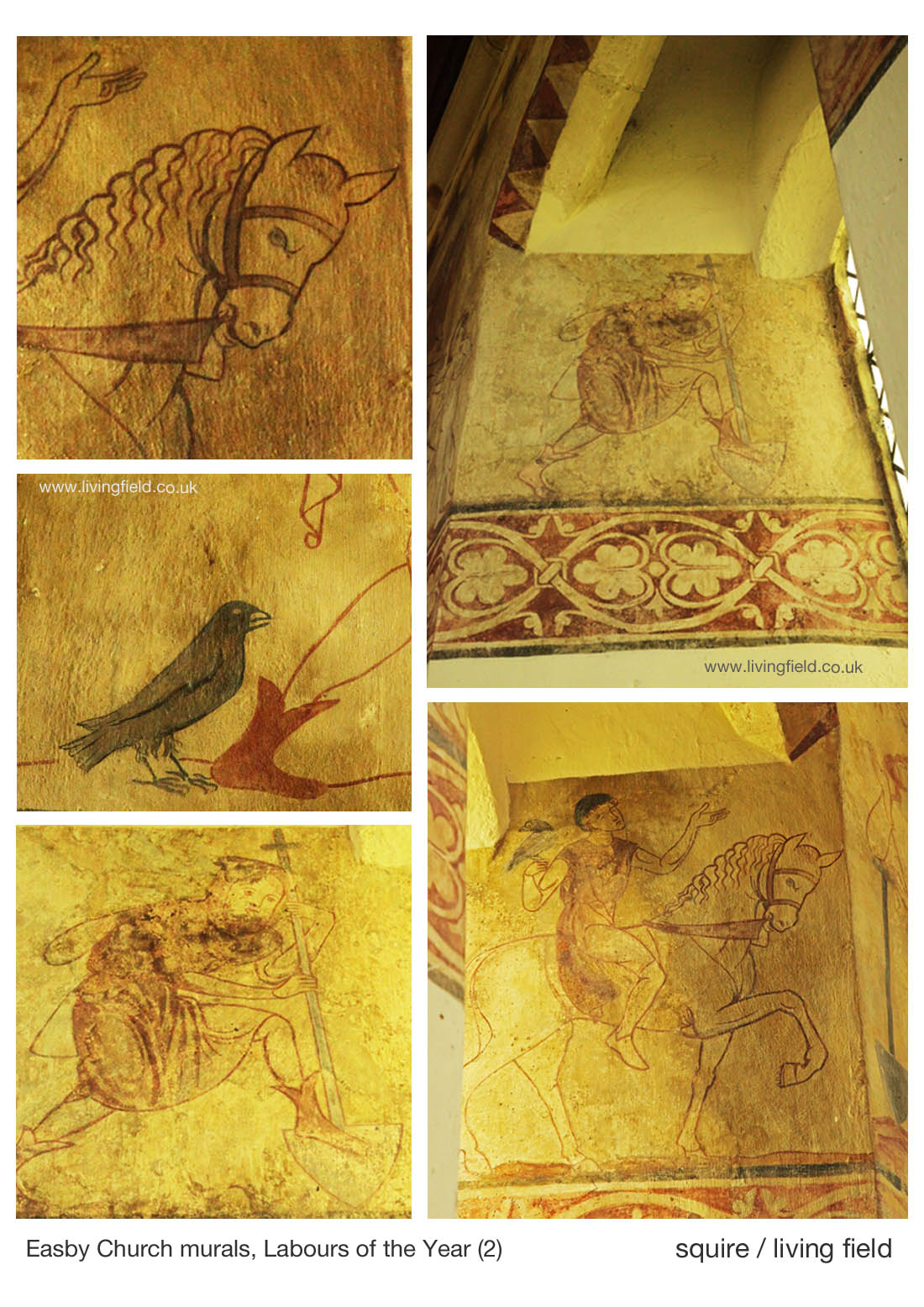

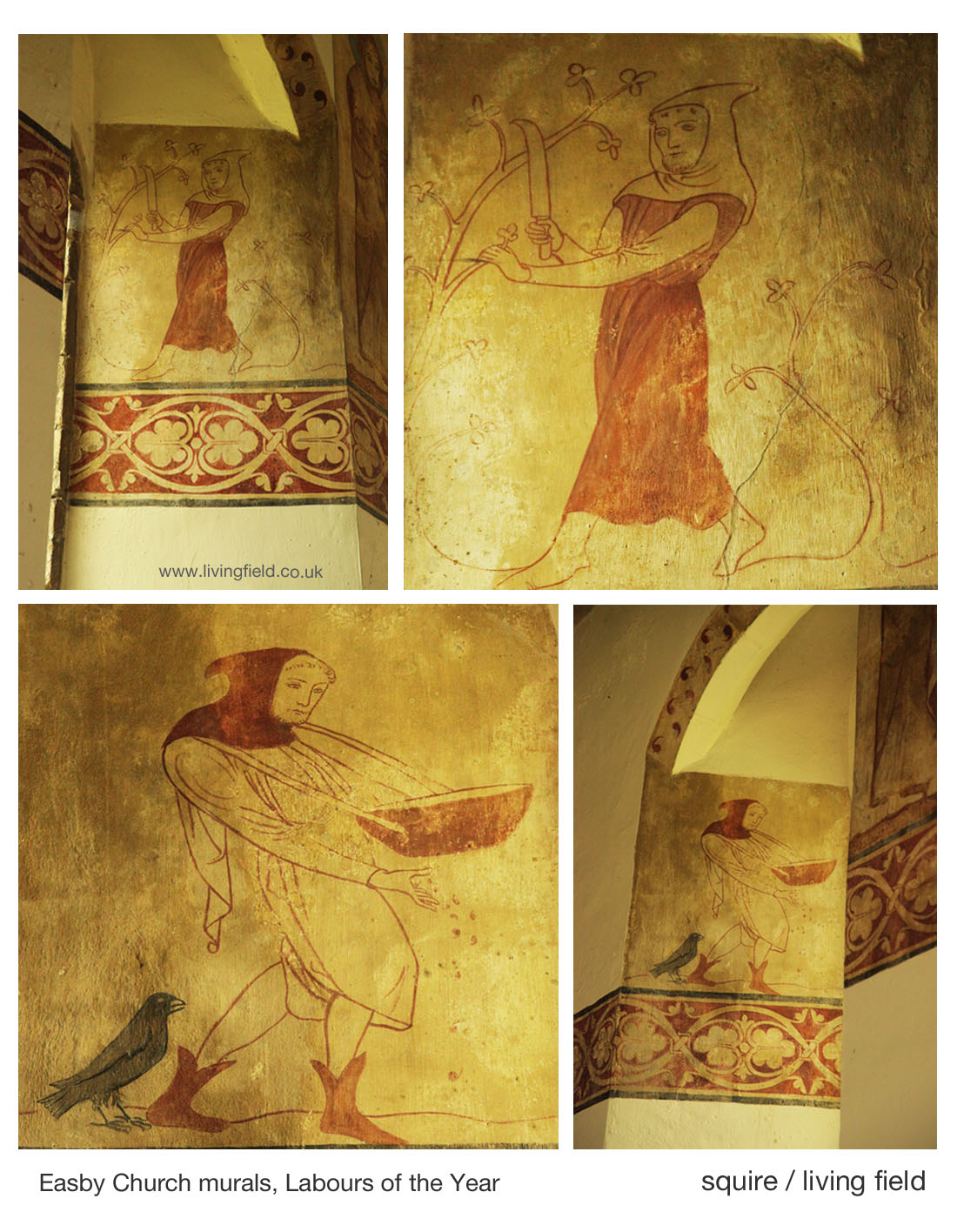

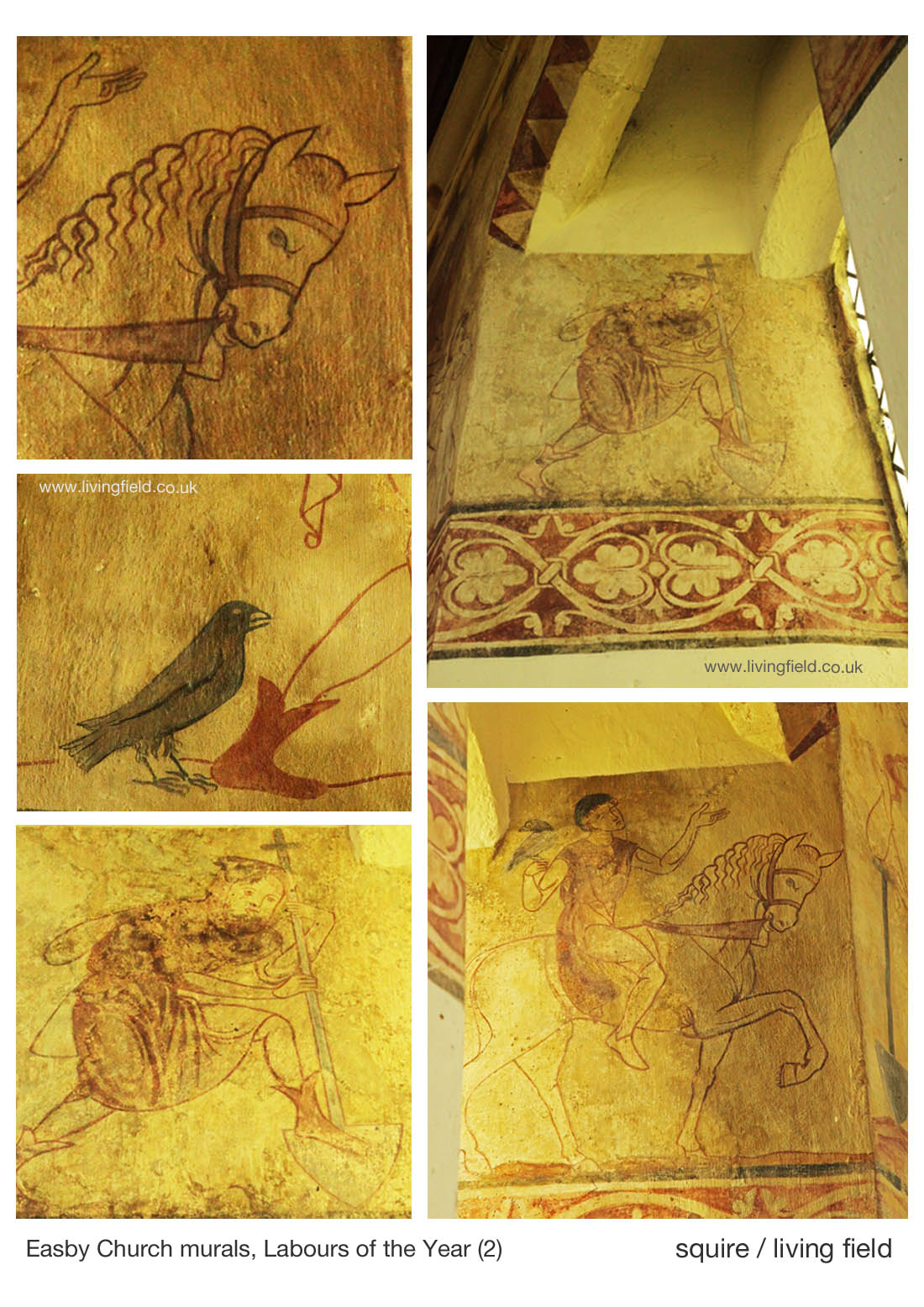

In the church of St Agatha at Easby [3] Yorkshire, four of what are thought to have been 12 murals remain of these Labours of the Months, dated to around 1250 along with several murals depicting scenes from the Bible. There are apparently very few other wall paintings of ‘The Labours’ from medieval Britain, and none to compare with these.

These murals were originally painted on dry plaster, but found covered with lime wash, presumably to prevent them being seen and defaced during Henry VIII’s purges of the monasteries in the mid-1500s. They were uncovered in Victorian times and restored again in 1994 [4]. The remaining 8 have not survived.

A notice in the church states that two of the remaining Labours are from spring, sowing and pruning, and the others, digging and hunting, from winter. Those of sowing and pruning are the best preserved.

The church at that time was next to a monastery, Easby Abbey, now a well kept ruin [5], and the resemblance of monks’ hair styles (tonsures) in the labourers depicted suggests that the painter’s models were working canons from the Abbey rather than common people.

Yet the presence of this ‘Labours’, so close to central Christian themes, and in a humble church, shows the importance of the year’s cycle to the people and the beliefs at that time. As in the great cathedrals, hunting on horseback with a hawk features in one of the four (lower right in the images above). The hawk itself looks more like a crow and not too different from the crow observing the sower.

Who was then the gentleman …?

Another of the murals, not part of the ‘Labours’, but one of a set on early Christian themes, shows Adam digging and Eve sat on a rock or tree stump spinning, symbolic mundane tasks that they would have to do for eternity after their ejection from the Garden in the book of Genesis.

These symbols of husbandry and craft have resonated throughout recent history, not least when the preacher for social justice and equality, John Ball [6] wrote in the 1300s not long after the Easby murals were painted:

These symbols of husbandry and craft have resonated throughout recent history, not least when the preacher for social justice and equality, John Ball [6] wrote in the 1300s not long after the Easby murals were painted:

“When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman.”

He was querying why privilege and power should still so dominate and make miserable the lives of working people in what was purportedly a Christian country. That power was uncomfortable with the idea of social justice and John Ball came to a violent end, being cut into pieces and displayed in different parts of the country.

John Ball’s memory has also been kept in writings and songs, notably that by Sydney Carter [6].

In the mural at St Agatha’s, Adam is fully clothed, and Eve not quite, but in the folk tradition they can be without. In the song “Old Adam” – which has a delving and spanning refrain – is the line “he never paid his tailor’s bills because he wore no clothes” [7].

Modern labours

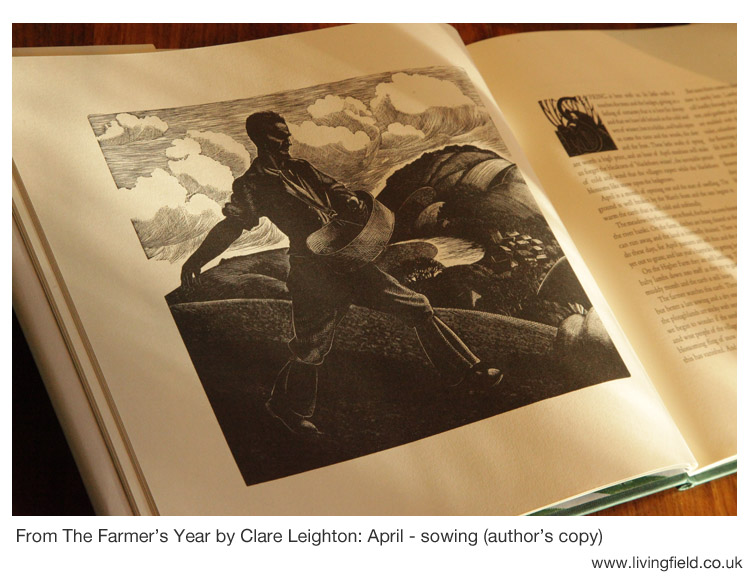

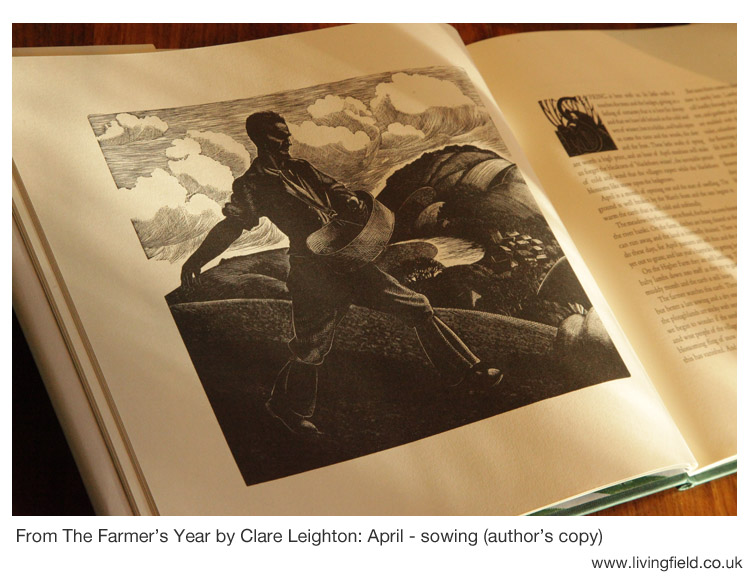

The Labours of the months was given a new treatment by the writer and artist Clare Leighton in her ‘The Farmers Year’ published in the 1930s [8]. She begins with the Labours of Lambing, Lopping and Threshing, then in the month of April, Sowing; and the time of the engraving is more than 500 years after Easby, yet the farmer is broadcasting by hand, carrying the grain in a basket slung in front of him.

Her sower strikes a similar pose to that in the Easby murals, but with right arm back after flinging the seed. Her sower is more rugged, of the earth, not with smock and tonsure but with weathered face and trousers tied below the knee and having a wife waiting for him at the farm.

Though she admits most sowing and other field work was then done with machinery, Clare Leighton chooses to engrave this sower, and writes ” ….. but here and there a farmer remains who still feels some warmth come up to him from the earth as he strides his fields, and to whom the land is a matter of emotion as well of economics.”

The crow?

The presence of the crow, following the Easby sower, recurs throughout the tradition. Crows observe the human condition, taking advantage where they can. In traditional song, two crows find a ready meal in a new-slain knight, deserted by his dog, his hawk and his lady. The crows are thinking aloud about which of them will feast on the eyes.

Of contemporary artists, Alan Stones has a special eye for crows and ravens [9]. In his lithograph – Brother Sun – a crow observes a man, a shepherd, coiling barbed wire. Another crow flies away low over the field. In a charcoal drawing, two crows peck before a gnarled hawthorn tree. His series ‘Divided self’ show crow-type birds standing on sheep and the series ‘Raven’ brings out the unearthly power of the great black birds.

The murals at St Agatha’s, Easby, are part of a European heritage and a continuing tradition [including colouring-in if that’s your fancy 10].

Contact / author: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk, visited St Agatha’s on 9 July 2017.

Sources, references, links

[1] Labours of the months: for general background and examples, see the Wikipedia page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labours_of_the_Months; and The Paradoxplace web site shows Labours and Zodiac in stained glass at Chartres, France c1217

[2] The illuminated manuscript, Très Riches Heures can be viewed at Public Domain Review: https://publicdomainreview.org/collections/labors-of-the-months-from-the-tres-riches-heures/.

[3] Easby Parish Church – a brief guide. Bargate Publications, Richmond, North Yorkshire, www.bargatepublications.co.uk. A notice on one of the walls states that the murals were originally painted on dry plaster and pre-date the Florentine Giotto (c. 1267-1337) and the Sienese Duccio (active 1278-1319). The church contains a replica of the Easby Cross, of sculpted stone, now in the V&A London. The photographer and historian Stiffleaf has a bank of images at http://www.ipernity.com/tag/stiffleaf/keyword/28360/@/page:69:18

[4] The Easby Church guide states: ‘…. they were uncovered during the Victorian restoration and restored again in 1994 by Perry Lithgow (a company specialising in architectural restoration)  assisted by a grant from English Heritage.’ More photographs of the murals can be viewed at Wasleys.org.uk.

assisted by a grant from English Heritage.’ More photographs of the murals can be viewed at Wasleys.org.uk.

[5] Easby Abbey was founded in the 1150s for the Premonstratensian Order, itself founded in about 1121 in Prémontré, in France. The Abbey was destroyed in the 1540s in Henry VIII campaigns. Information at English Heritage http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/easby-abbey/

[6] John Ball: the Wikipedia entry gives general background. Sydney Carter wrote the song ‘John Ball’ for the 600th anniversary of the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381. Perceptive commentary at ‘Songs that grow like trees: an appreciation of Sydney Carter (1915-2004)’ on the web site Early Music Muse – musings on medieval, renaissance and traditional music by Ian Pittaway. Chris Wood sings ‘John Ball’ on his album Trespasser: ChrisWoodMusic.

[7] The traditional song “Old Adam” is performed (2016) by Fay Hield and the Hurricane Party on the CD album Old Adam, 2016, Soundpost Records, www.fayhield.com.

[8] Clare Leighton, 1898-1989, writer, artist and engraver. For examples of works, see clairleighton.com. Source: Leighton, C. 1933. The Farmer’s Year – a calendar of English husbandry. Little Toller Books, Dorset.

[9] Alan Stones at www.alanstones.co.uk. ‘Brother Sun’ and other early lithographs can be viewed at Lithographs – Farming (1984-1992); crows and ravens at Lithographs (1996-1999).

[10] Institute for Medieval Studies University of Leeds

Downloadable page for colouring, Labours of the Months, January to March https://www.leeds.ac.uk/arts/download/2753/labours_of_the_months

[Edited 17 September 2017]

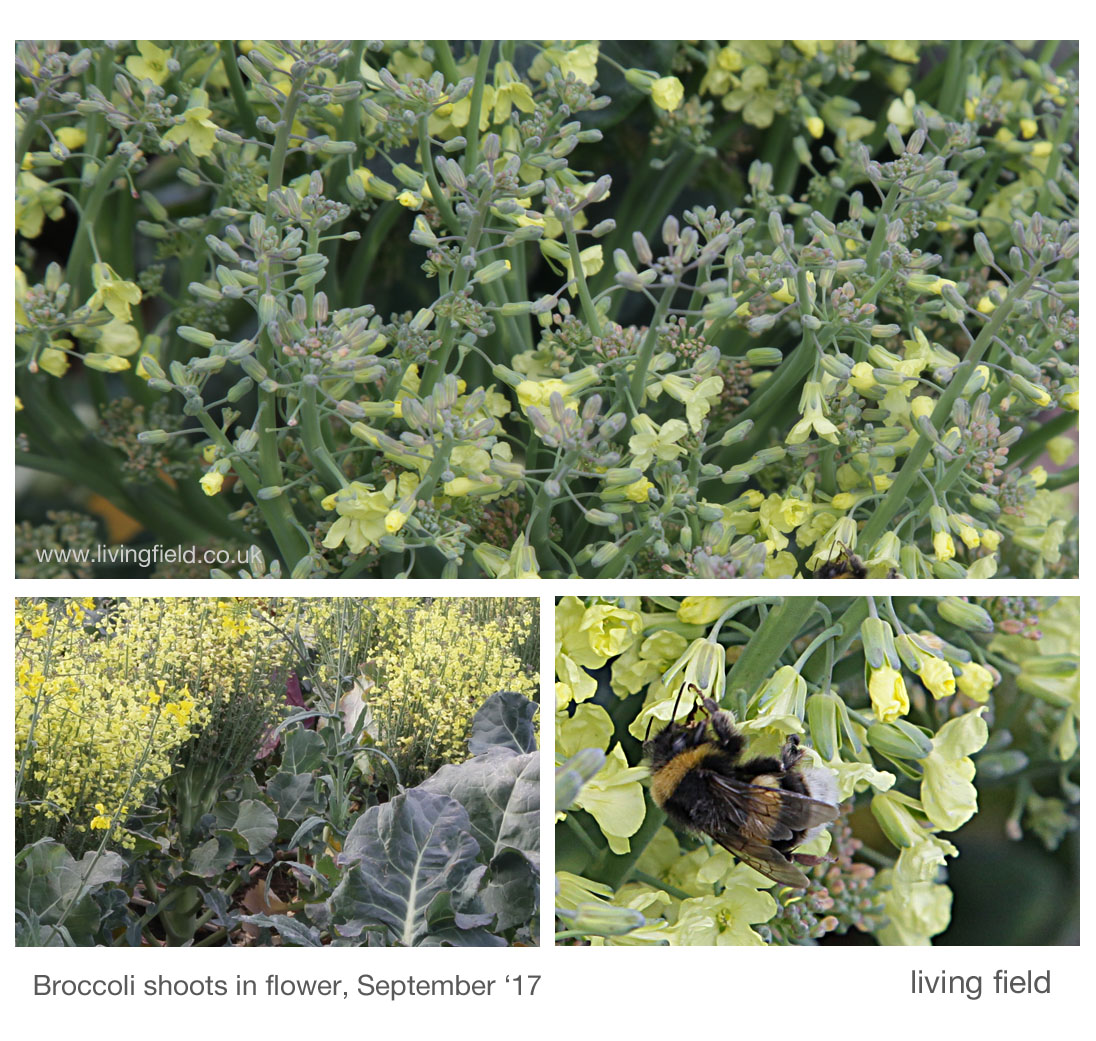

The photographs above show a field of broccoli in east Perthshire, flowering in mid-September after most heads had been harvested. The cultivated plants have the same pale yellow flower colour as their wild relative. In this field, some rows took to flowering more than others, perhaps indicating the planting of different varieties.

The photographs above show a field of broccoli in east Perthshire, flowering in mid-September after most heads had been harvested. The cultivated plants have the same pale yellow flower colour as their wild relative. In this field, some rows took to flowering more than others, perhaps indicating the planting of different varieties.