The equinox in autumn usually occurs during the day of 21 September. Hours of light and dark are equal but the dark period will now increase quickly as the year moves towards the sun’s low point, the winter solstice in December. It is the time of harvested fields and autumn fruit in the hedges.

Images around the autumn equinox

1 Ripe elderberries, some already taken by birds (LFG). 2 The weight of harvest – five-high straw bales on soil. 3 A field sown late with game cover, mostly borage and Phacelia, flower shown of the latter, Glen Clova.

4 Flower of marsh mallow, with insect visitor, one of the slowest plants to develop in the year and the latest to flower (LFG). 5 Bright red hips of the wild rose. 6 Part of an ‘ear’ of a wheat landrace (Red Standard), the latest of the garden’s cereals to mature in 2014 (LFG).

7 Isolated trees in post-harvest landscape, south Angus. 8 Apples from a tree in the Carse of Gowrie. 9 Straw bales from cereal harvest, waiting for collection.

LFG – grown and photographed in the Living Field Garden.

Solar energy and earth’s temperature

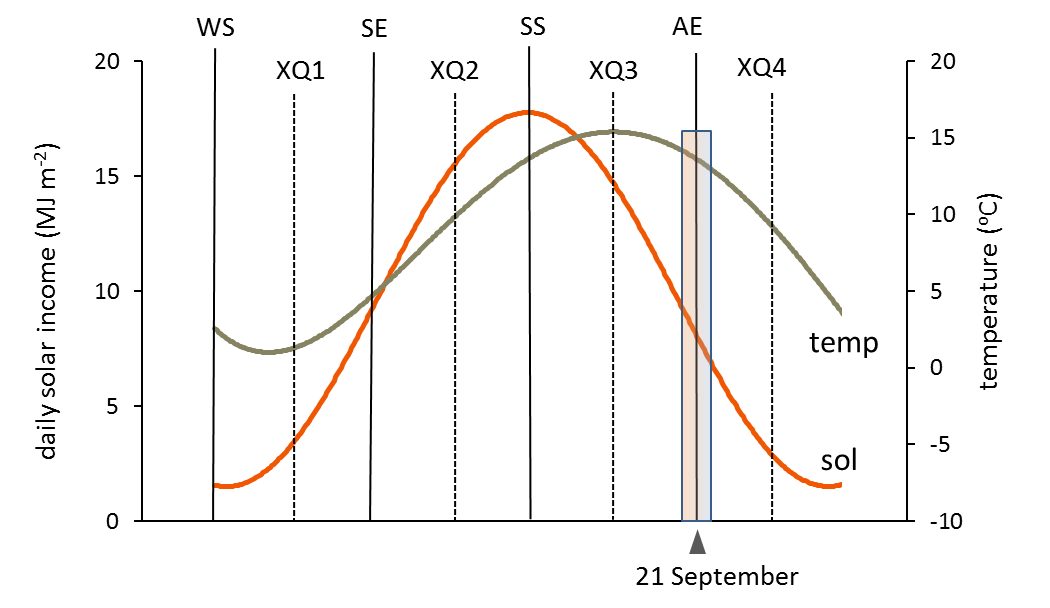

The solar income at XQ3 is just below half what it was in late June, yet the climate still offers good growing conditions, temperature still close to the annual maximum .

Solar will now fall quickly day by day, while temperature lags increasingly and it can still be warm. Other conditions at this time, particularly wetness, determine whether the ground can be prepared in time for autumn sowing.

[Source graphs at The Year explain how the sol-temp graph was derived and examples of the day to day variation.]

The crops

The equinox is the scene of the big trade-off, and caution usually wins, but not always. The weather is still warm and the solar income, though declining, still high enough for bulking crops with some speed. Yet autumn approaches and with it the threat of weeks of wet, which if continuous without respite is a wet that will cause grain to germinate on the plant and hay and straw to lie mouldy. So the imperative, despite the lure of sunny days to come, is to get the harvest home, as early as late August for winter barley and winter oilseed rape and throughout September for winter wheat and spring barley.

Some fields are ploughed soon after harvest. About a tenth of those are sown almost straight away with winter oilseed rape. For crops such as this, every week’s delay brings a loss of yield next year: in the next two months they need to grow a fine strong leaf to withstand the winter cold and wet and to soak up the solar next spring. The corn crops – winter wheat and barley – can go in later, but not much later. The timing of operations and sowing in autumn is crucial.

It’s also a time when soils can be compacted and, if it happens year on year, ultimately ruined. Those neat ‘tramlines’ may be forgotten at harvest, when machines rove over fields, baling and collecting bales; and sometimes bales are piled on bales to compress the essential living medium of soil beneath them.

So this equinox is warm and bright, but farming is working to end the harvest and is turning to next year’s crop.