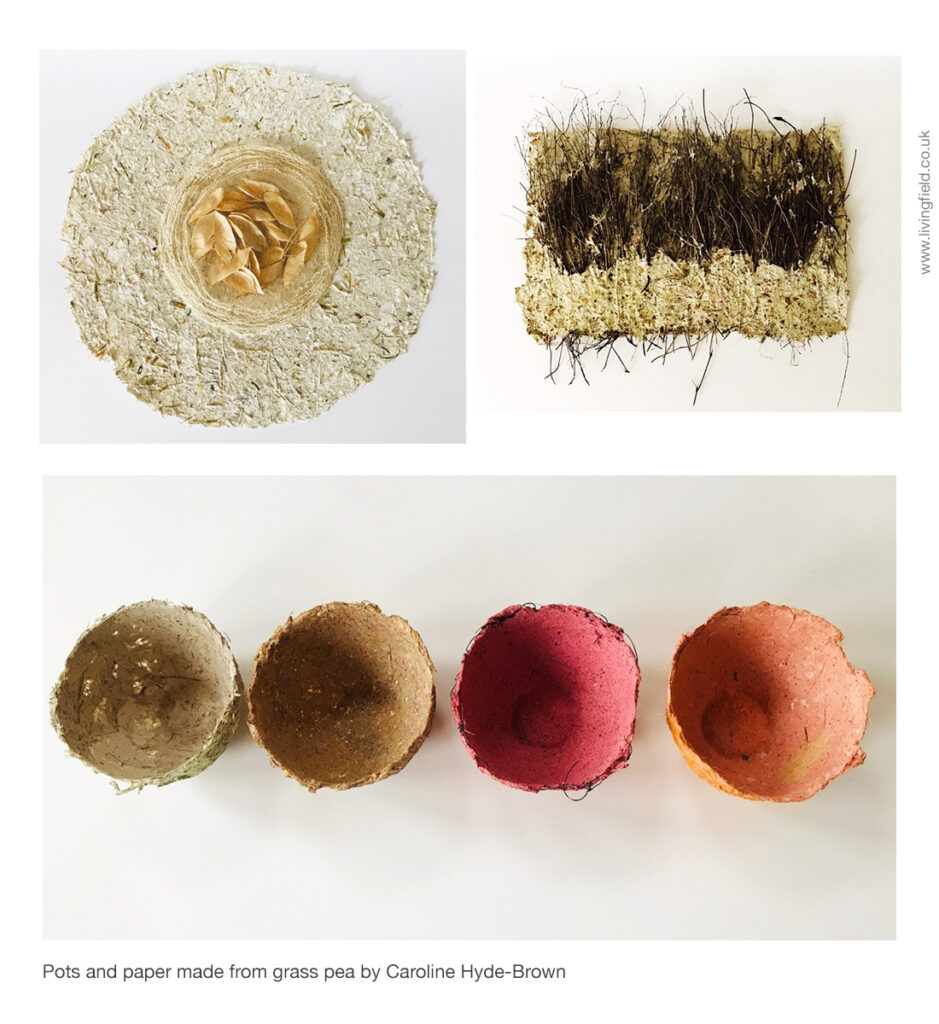

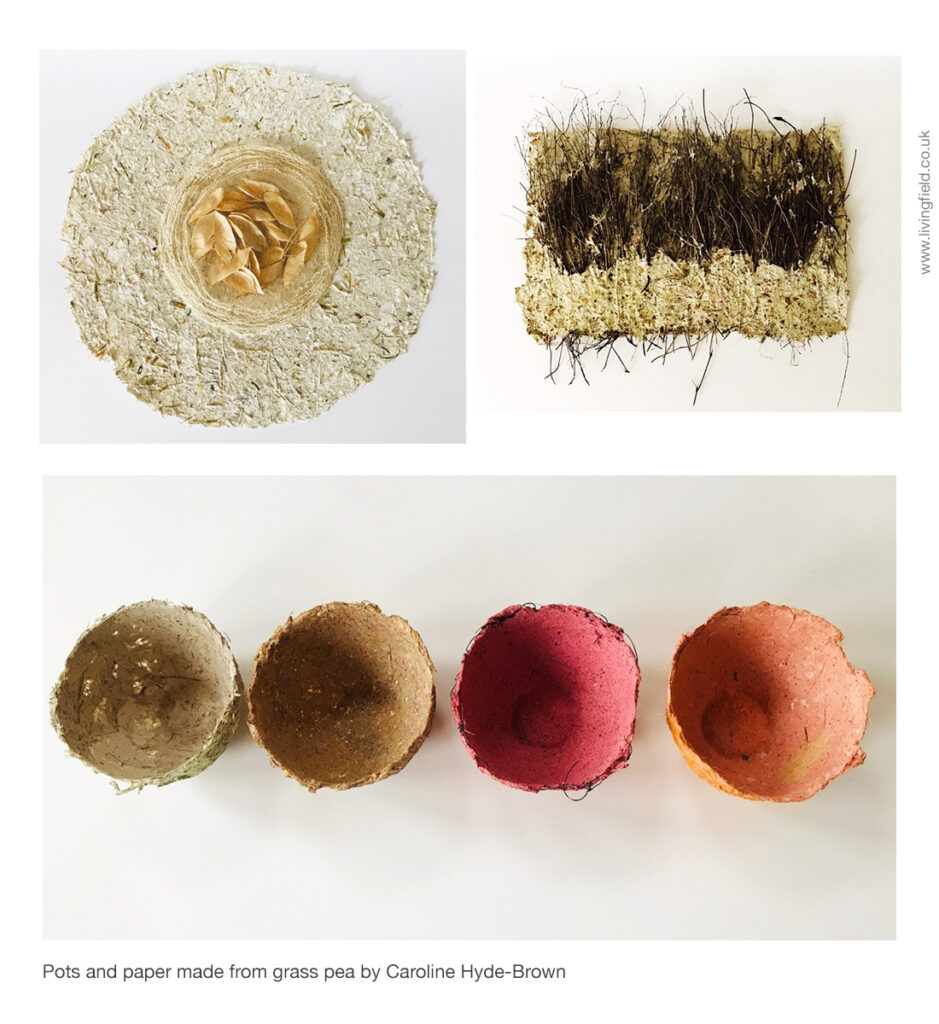

Caroline Hyde-Brown www.theartofembroidery.co.uk sent the Living Field these images of pots coloured with natural dyes and crafted paper, all made from the legume Grass Pea. More to follow ….

sustainable croplands

Caroline Hyde-Brown www.theartofembroidery.co.uk sent the Living Field these images of pots coloured with natural dyes and crafted paper, all made from the legume Grass Pea. More to follow ….

Following the Nourish Scotland conference in November 2019, the Living Field began thinking about how it might best support those working towards a sustainable future for food and agriculture [1]. Then early in 2020 the pandemic hit, raising searching questions as to whether the food system could cope.

In March 2020, Pete Ritchie from Nourish Scotland, wrote a blog [2] putting the case that once the initial panic has receded, the international food system would adapt, the empty shelves would be re-stocked and no one in this country ought to go hungry. Nourish, through their blogs, web sites and conferences are at pains to point out that no one should go hungry in the UK because of shortage of food. Where they are hungry or malnourished, it would be due to other factors, such as social inequality, not the amount of food available.

Nourish were correct, but they were not giving the thumbs up to the current state. The blog writes that the food system – “ … generates massive environmental damage, monumental food waste, exploitative work practices and a disastrous mismatch between what we need to eat for health and what we are being sold.”

Dysfunction and mismatch are not simply other people’s problems. The blog continues – “ …..it would be good if Scotland were to produce more of what it eats, and eat more of what it produces.”

The argument raises the greater issue of the choices that can be made – whether to create a more equitable food system or stay with the current dysfunctional mix of hunger and plenty. Analysis by the Food Foundation [3] indicates the pandemic is driving more people into malnutrition and hunger: the food is there, but unaffordable or out of reach.

Yet on the continuity of supply during the pandemic, the food system has adapted. Would the same be true following any global emergency?

The food system supplying Scotland and the UK was able to recover because of particular features of this pandemic. Farming and food stocks in most parts of the world have been little affected so far. With some exceptions, channels for imported food have remained open. It is too soon to say whether more will be restricted if lockdown and social distancing continue, but the chances are they will not be. However, other global crises could have far greater consequences.

Imagine if imports had been shut off. The Food Atlas [4] produced by Nourish Scotland in 2018 shows the country’s reliance on imports. While some food supply chains can be satisfied by local produce, those supplying the staple carbohydrates, plant protein and vegetables are particularly vulnerable.

If imports had been closed down, the country would be in trouble. Could this happen? There are two main possible causes: the food is there but imports are stopped, for example, by blockade due to international hostilities; or the food is not there to buy, because the countries producing it keep it themselves or have suffered a catastrophe in their producing regions (e.g. ash from volcanic eruption). Both have happened in the past. They will happen again.

After the food insecurities the 1940s, a post-war Agricultural Expansion Programme was initiated to raise production and shift the balance more towards grain than grass. The programme worked, aided by technological advances in machinery, agronomy and crop yield potential. Yet within a few decades, the country came to export much of its agricultural production and was again dependent on imports for food.

In an uncertain world, a country needs to keep its borders open for trade, both ways. But it also needs to ensure it can feed itself if it has to. The balance needs to be redrawn: local production raised, more food grown than feedstocks for alcohol and livestock, with a shift in emphasis to ‘building’ rather than degrading the agro-ecosystem. All this is possible.

An extended version of this article is published at Food security in the pandemic. More on the food system is available online [7, 8].

[1] Nourish Conference 2019 – Lessons for the Living Field.

[2] Nourish Scotland. Making the food supply chain work for everyone. By Pete Ritchie, 24 March 2020.

[3] The Food Foundation published some recent statistics on 22 May 2020: Food insecurity and debt are the new reality under lockdown.

[4] Nourish Scotland’s Food Atlas: http://www.nourishscotland.org/resources/food-atlas/

[5] To find out more about local food systems, search these organisations:

[6] Examples of relevant articles on the Living Field web site: City University’s food systems diagram: Five spheres around the food chain. Ten crops from three continents make this simple meal: Beans on Toast revisited. Barley, oats and wheat: Three-grain resilience in Atlantic zone agriculture.

Author/contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com

Where next for the Living field! Here we look at Nourish Scotland’s Conference and Food Atlas for inspiration. We conclude that the Living Field should remain within its core areas of environment, community and healthy eating, while working towards better integration of these core activities to link agriculture and the human food chain.

The Living Field project began 19 years ago. The name and concept were proposed by Geoff Squire in 2001. The garden and its habitats were designed by Gladys Wright, built by science and farm staff and opened to the public in 2004. It’s time to assess where we are and what might come next. We therefore examine some local and international initiatives in the food chain to help judge where the Living Field stands.

Of the many organisations we have worked with over the years, Nourish Scotland [1] offers the most comprehensive set of practical aims based on improving the food chain as a system, as a set of connected and interdependent parts that need to evolve as a whole.

Here we look at one of Nourish’s achievements – the Conference held earlier in November 2019. Their Food Atlas of 2018 will be featured later. In each case, Nourish defined those parts of the system that need to be in good shape for the whole to work effectively.

The Nourish system goes well beyond the biophysical properties of soil, agronomy and climate to include human health and wellbeing, the end of malnutrition and hunger in Scotland and the cultural and political will to make this happen. As a further step in our own evolution, we consider those topics from the Conference in which the Living Field already operates and those it might need to move in to.

The Conference held in Edinburgh 21-22 November 2019 aimed to devise a Game Plan for a Good Food Nation. Its basic premise is that the food system is broken and needs radical change. It brought together people with a very wide range of interests and expertise. (Nourish will publish a full report in due course.)

People attending were divided into groups of about 8, each group to consider where things stand and what can be done to bring about major change. A diagram, designed by the Centre for Food Policy, City University [2], helped to guide discussion: the food chain lies in the centre, surrounding by five ‘domains’ or ‘spheres’ that affect and are affected by the food chain – environment, society, economy, politics and health (Fig. 1). Each person indicated their expertise by placing paper dots on the diagram. The domains were all well covered.

The Food Chain in the centre is made up of of 8 topics [3]. The five surrounding ‘spheres of sustainability’ go farther than the widely used three (environment, economics and society) or four (those plus politics) to include health. Each sphere consisted of 6 essential topics [listed at 3].

Fig. 1 Food chain diagram (top left) used at the Nourish Conference reinterpreted to show main activity in the Living Field project: the bigger the letters, the greater the activity in the Living Field. Full list of topics at [3]. The food chain diagram was created by the Center for Food Policy, City University [2], used with thanks.

The diagram is shown upper left in Fig. 1, but to examine our activities more closely, the spheres are reproduced as boxes drawn in the same colours as in the original. Each box lists those sub-topics that the Living Field has been active in over the past 15 or more years. We have a strong base in many topics of the Food Chain from production to eating, but have done little in processing, retail and waste.

Of the surrounding spheres, most activity has been in three – Environment, Health and Society – where we combine practical knowledge in the garden and farm with online activity in this web site.

Looking at the possibilities, it would be difficult for us, with a base in the Garden, to move far into economics and politics. Rather, the scope for expansion lies through improving the connections and overall integration among topics that we already cover, with some additions such as waste.

For those readers with long-term interest in the Living Field and its future, we summarise below our work on the Food Chain and in the spheres of Environment, Society and Health, providing links in each case to articles on this web site. Finally, we look to the future.

Fig. 2 Schoolchildren visiting fields at the James Hutton Institute, looking at crops and the bugs (invertebrates) that live in them – hosted by the Living Field.

The Living Field has been active in four of the main topics in the Food Chain [3]. Agricultural production and Farm inputs have been core activities, both in the garden and the surrounding farm. A range of cereals, legumes and tubers, some bred at the Institute, have been grown in most years. We have interpreted many aspects of Research and Technology and their practical application on the Hutton Farms for our audience of schools and the public. Eating has concentrated on the use of home-grown grains, pulses and vegetables.

There has been some integration of these topics. Our ‘grain to plate’ – or more graphically ‘seed to sewer’ promotions – have looked at links along important segments of the food chain. And we have explained that, while most of our food is imported and relatively little produced locally, there is scope to raise home grown production.

Examples of Living Field web articles on these topics Crop diversification. Ancient grains at the Living Field – 10 years on. Energy and light – no life without the sun. The Year. The barley timeline. The Brassica complex. Beans on toast – a liquid lunch. Three grain resilience. Effect on corn yields of the 2016 winter flood. Seed to sewer – the water footprint. Resilience to the 2018 drought. Food production from the first crops to the present day. Great quantities of aquavitae. Crop-weeds.

Fig. 3 Diversity of crops: panel of photographs to show the range of crops and other useful plants grown in the Living Field garden (original images by GS).

Of the 6 topics in the sphere of Environment [3], the Living Field has been active in Biodiversity, particularly as it affects ecological functioning, and Land use and Soil. The need to study and display diversity among managed and wild plants of the croplands was one of the main reasons for constructing the micro-habitats in the garden.

In Water, we have looked at both the water cycle as it affects agriculture and to a lesser degree the use of water in processing. Less emphasis has been given to Climate and Air, other than through having to respond to weather, as do all gardeners and farmers, and writing articles on climatic patterns and shifts.

Examples Pollinator plants. The meadow. Hedge and tree. Pond and ditch. Crop diversity. The late autumns floods of 2012. Resilience to the 2018 drought. Winter flood. Dust bowl ballads. The beauty of roots. Booting small scale seed production. Kidney vetch and the small blue.

Fig. 4 Biodiversity in the Garden – collage of images taken in the Living Field garden arranged to show the micro-habitats with their plants and invertebrates, all interconnected. Original images by Stuart Malecki / Living Field.

The Living Field has placed Education centrally from the beginning, offering visits from schools and the public and working with formal education to produce teaching aids, notably the Living Field CD which was distributed to all schools in Scotland and had been widely requested from overseas (though is no longer updated). Working within the wider Community has exposed many people to the issues being discussed here, for example through various open events including Open Farm Sunday and public road shows.

In Culture, we have promoted the existence of our traditional crop landraces, notable bere barley, and explained the transitions in farming that have led to the present state. Several artists and writers have worked with us to extend the Garden’s activities to new appreciative audiences.

Examples: Jean Duncan Artist. Open Farm Sunday 2019. The garden at Open Farm Sunday 2017. What are landraces. Bere line (rhymes with hairline). Tina Scopa – Edaphic Plant Art. The Crunch at Dundee Science Centre. Transition Turriefield. Shetland’s horizontal water mills. On the edge (rigs on Lewis). More than landscape. Dundee Astro. Anniversary designs and sketches.

Fig. 5 Living Field roadshow at a Biodiversity Day, Dundee Science Centre, showing: top right c’wise, people at the event, learning how to make bread, two types of edible insect, bread made from insect flour, gluten and a sheaf of emmer wheat, with (centre) cereal grain.

The project has promoted the benefits of healthy eating, mainly through growing and locally processing pulses, vegetables and grains. A major living exhibit in 2017 emphasised the nutritional content of different types of vegetable. The wider community has shown how to prepare and cook healthy plant products. Our work touches on food safety and general wellbeing, but much less so if at all on other topics in this category [3].

Examples Vegetables in the garden. The Garden’s vegetable bounty. Can we grown more vegetables. The vegetable map of Scotland. Legumes in the garden. Peasemeal, beremeal, oatmeal. Feel the pulse. Scofu – the indigenous Scottish tofu. 2Veg2 pellagra. Vegetables markets of the world: Little India, Inle, Bangkok.

Fig. 6 Vegetables grown in the garden, sectioned: cauliflower, carrot, onion and beet (images by Living Field)

The Living Field project has had little activity in spheres of Politics and Economics. The web site has touched on issues in rural policy, such as CAP Greening, and value-generation, for example through new legume products, and web articles have pointed to our reliance for food security on international trade in commodities. Yet in general we have kept out of Politics and Economics.

How far then should the Living Field enter into Politics? There is scope for more activity in topics around tax and subsidy but little option, given our status as part of a research institute, to enter into debates on party politics, power relations and governance structures. We have not been a campaigning organisation. Rather, we contribute basic knowledge and experience which we hope will be useful to others.

Similarly, how far into the Economy? There is certainly scope to raise our contribution to generating value in agricultural products, mainly through public outreach in food technology as developed within the Institute. There is perhaps more scope in comparing the economics of various crops and forms of agriculture, and the associated trade in these products, but to do that would need closer involvement from those with the right skills.

Fig. 6 Each year the garden grows a wide selection of useful plants in addition to the food crops. Here are some from 2019: top left c’wise, flowering stems of dyer’s weld, flower of dyer’s coreopsis, great mullein, dyer’s greenweed with wild carrot heads emerging, chicory flowers, and (centre) painted lady on knapweed (www.livingfield.co.uk).

The Centre for Food Policy’s concept of five spheres around the Food Chain is a challenge. The Living Field has worked in two of the spheres from the beginning – Environment and Society – and has increased its activity in a third – Health – for example through diet and nutrition. The other two spheres, Politics and Economy have been left to other organisations adept in these areas.

Talking to people both at the conference and elsewhere, it looks like the greatest value offered by the Living Field is to continue concentrating on its core areas. Very few small projects can grow and display year on year around 200 plant species that are or have been useful to people as food, medicinals, fibres and dyes.

In looking to the future, the work needs to be more directed. Progress since 2001 has been a fairly random walk through plants and their cultivation since the neolithic. The speed and direction of this walk have been determined mainly by external events and the interests of the community – the scientists, artists and practical people who have contributed their time, effort and knowledge to the project.

There is scope therefore for the Living Field to take on the Food Chain more holistically by integrating Environment, Society and Health with an awareness of Economics and a nod to Politics. This more purposeful approach should show the progression of products along the food chain, developing several case studies from the cereals, pulses and vegetables.

An example of how the project might operate in the future might learn from the Vegetable Map of Scotland [5]. Gladys Wright had the idea of constructing the Vegetable Map as a living entity in the Garden. The idea came from earlier web-work with Nourish in which we constructed a digital map of the country showing where the various legume and vegetable crops were grown. But when the map was made real, growing in the Living Field Garden (shown right) the wider interest was immediate – here’s the land, here are the vegetables now grown – and here’s what could be grown if the food chain was operating for the benefit of all.

We have already begun this to a degree in association with the Hutton’s lead in the EU TRUE project on legumes in the food chain [4]. Taking Scotland’s pulses, peas and beans, as an example, the Living Field has describe their history of cultivation, shown how to grow them, their agronomy and environmental benefits including nitrogen fixation, and explored the potential for new uses and higher value in products such as Scofu. Yes, the Scottish tofu!

And we could extend the line of thought and practice: here are the benefits for environment and health … and this is what it would take in the form of support to farming to achieve these benefits ….. and perhaps most important of all, here is the public buy-in and political will needed to make it happen.

There’s much to think about …. and not least where the money comes from for the next phase.

[1] Nourish Scotland: information on the conference at Game Plan for a Good Food Nation.

[2] Conference Food Chain diagram: Centre for Food Policy, City University of London http://www.city.ac.uk/foodpolicy. The diagram was published in the following brief: Parsons K, Hawkes C, Wells R. 2019. Brief 2: What is the food system? A Food Policy perspective. In: Rethinking Food Policy: a fresh approach to policy and practice. London: Centre for Food Policy. Available through this link.

[3] The Food Chain comprises: Farm inputs, Agricultural production, Research and technology, Processing, Distribution/transport/trade, Food retail/service, Waste/disposal and Eating. The sphere of Environment comprises: Land/sea, Soil, Water, Air, Climate and Biodiversity. That of Society: Education, Livelihoods, Gender, Media and advertising, Culture and Community. Of Health: Wellbeing, Food safety, Environmental health, Diet and nutrition, Antibiotic use and Workplace safety. Of Economy: Trade, Jobs, Skills, Competitiveness, Value generation, Allocation of resources. Of Politics: Legislation, Policy, Power relations, Tax/subsidies, Governance structures and Political parties

[4] EU TRUE Transition Paths to Sustainable legume based systems in Europe. TRUE Project home: https://www.true-project.eu/

[5] Current and potential vegetable production in Scotland was explored in an article titled Can we grow more vegetables? from which arose the living structure in the Vegetable map made real.

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk.

[Online 5/12/2019, minor edits and new links 17/12/2019 and28/12/2019]

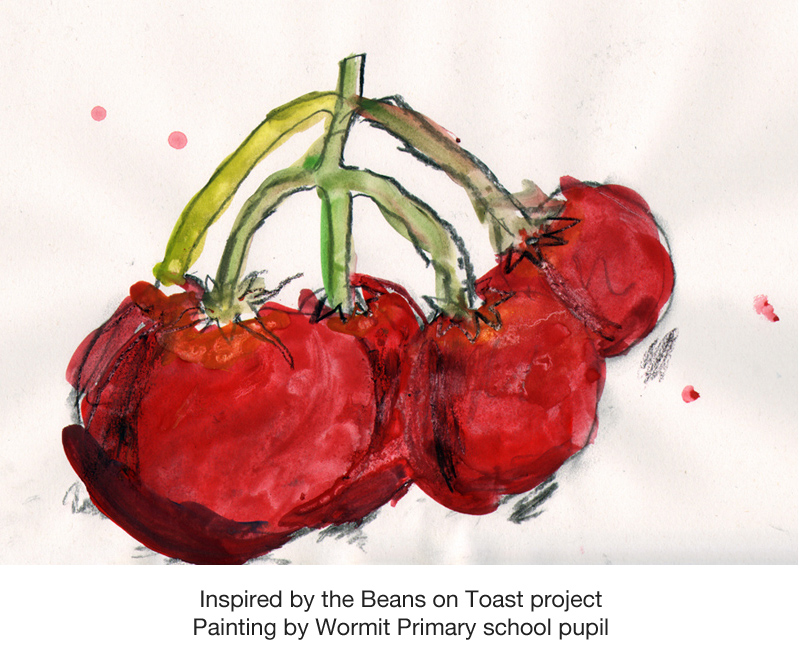

The famous Beans on Toast Project was started 7 years ago by student Sarah Doherty and artist Jean Duncan with Geoff Squire and other members of the Living Field team [1]. The project looked at the origins of this seemingly simple meal.

Not so simple in fact – 10 crops, grown in four continents and using masses of water and other precious resources – the product of a highly complex supply chain leading to a tin, a packet and a tub.

This example of the worldwide growing and sourcing of products that go into the food we eat has been used many times by the Living Field, most recently at a Citizen’s Jury event at the Scottish Parliament in March.

Sarah’s been reflecting on the project. She writes –

“Seven years on, I look back at the ‘water footprint’ for the Beans on Toast project as an eye-opening experience!

It was a reminder that there is a story behind everything. Almost everything we eat has travelled a long way to get on our plates. For so much water to go into the humble beans on toast – it baffles me how much more water and effort goes into producing other things.

I recently took up sewing and have been struck at how expensive it is to buy material for making home-made clothes. When mass- produced for high street stores, clothes may seem easy and cheap. However, making material is an energy and water intensive process too often involving crops for fibres such as cotton and linen.

I’m certainly more mindful of this now which is why I’m learning to cut my wardrobe down to what I really use and like the most!

Geoff was asked to attend a Citizen’s Jury as a specialist assisting the Jurors with background information on the topic being considered.

He used the Beans on Toast example [2] to show, first, that much of the food we eat is not grown here but imported, and second, that most of our pre-prepared food is made from mixing the products of many different crops grown using the resources of other countries.

Beans on Toast relies on haricot bean, tomato, oil palm, soybean, wheat, maize, sugar cane, paprika, onion, and oilseed rape ….. and that’s just the main ingredients. And the food on one plate of it needs several bathfulls of water.

Beans on Toast is an excellent example to show that we need to use less of other countries’ resources and more of our own.

What’s known as the legume gap or protein gap – the difference between home grown and imports – is massive. We grow just a few percent of the plant protein needed for feeding people and farm animals.

We have been adding to the information on sourcing food and estimating how much water and nutrients it takes to grow and process food like this [3]. Beans on Toast lives ….

To see the original pages –

[1] Sarah was studying at Durham University when she worked at the James Hutton Institute for about a year in 2012 . She has kept in touch. She last visited in summer 2018. Jean Duncan, who worked with Sarah on educational projects with local schools, still works with the Living Field.

[2] The Citizens Jury event was held at the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, 29-31 March 2019. Information at the curvedflatlands web page Citizens Jury at the Scottish Parliament.

[3] The EU TRUE project runs currently, coordinated at the James Hutton Institute. Among its aims is to study the global food and feed supply chains, to cut waste and and to raise local production. It’s full title is Transition Paths to Sustainable Legume-based systems in Europe https://www.true-project.eu

Contact for this page: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

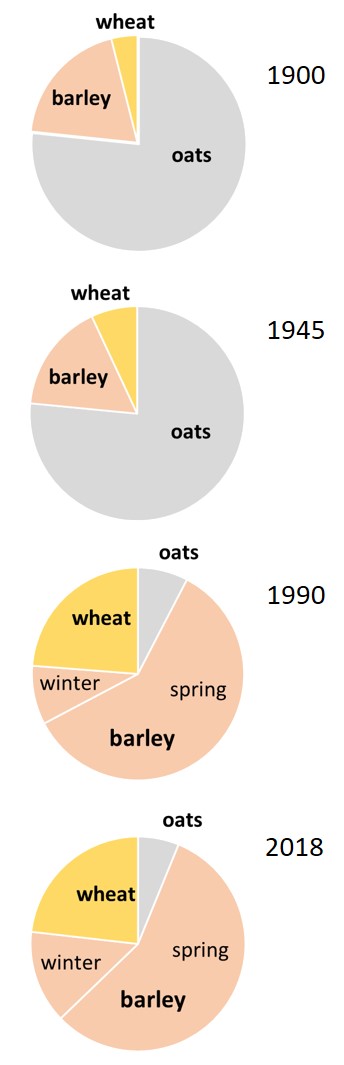

The north-east Atlantic seaboard has grown three main grain crops – oat, barley and wheat. All originated in the east Mediterranean or west Asia, but all find the climate here good for their growth. Most years that is.

The fall in output of the main staple grain crops in 2018, and before that in 2012, due to unusually bad weather, raised many questions as to how food and alcohol production would be affected if the climate continued to vary between wet and dry. The crop in 2012 suffered from cloudy skies causing slow plant growth, and then very wet soil that made harvest difficult. That in 2018 suffered from lack of water mid-May, at just the point when the crops were starting their main phase of growth.

Yet in neither year did production collapse. Total grain output from wheat, barley and oats fell by little more than a tenth of the average. Perhaps the varied needs of the three grains give cereal production here its ability to withstand years of bad weather. Historical change in this combination of grains may tell much about how agriculture can cope with the future.

Here, we look back over 150 years to see that the balance of the three grains and other crops has undergone major change, most of it not due to the weather, and ask whether the three grains give production some resilience – a capacity to withstand shocks, to adapt and continue.

In and around 1900, and for many decades before that, oats was by far the most widely grown grain crop in the northern part of Britain. In the crop census for Scotland [1], oats occupied more than three-quarters of the cereal area, and barley most of the rest. Wheat was minor. Few other cereals were grown – a little rye and some ‘mixed grain’ usually consisting of oats and barley.

It was a time of great change, most of it considered negative for home production. The area sown with cereals decreased as did that of the ‘root’ crops (turnips and swede) and also the grain legumes (peas and beans). They all gave way to grass, to feed cattle and sheep, with the result that the country was far from self-sufficient in grain at the time of WWI.

The areas grown with cereals and other arable crops kept on falling until the start of WWII when the need for home-grown food and feed caused some of the grass to be re-ploughed and sown with arable. The proportional areas of the three cereals remained the same, except for a little more wheat.

Yield per unit area had not changed much from 1900. Something had to happen. The privations of the war years and reliance on imports to feed the country spurred government into action. Plans were laid to raise farming output, but it was well over 10 years before there was any improvement in yield.

The phase of ‘intensification’ really began in the 1960s – machines could plough deeper, mineral fertiliser was readily available and new crop varieties were introduced able to allocate more of their mass to grain rather than straw. By the 1980s, yields had more than doubled. This result of intensification was a major achievement, reproduced in many parts of the world (The Green Revolution).

The largest single change here during that time was a shift from oats to barley and wheat. They were more profitable than oats and could now be grown to higher yield and over large areas with the fertiliser and pesticides that became readily available. Most of the wheat and about 20% of the barley were autumn-sown winter crops. They were able to survive the cold of winter and be ready to bulk up on the sun’s energy as early as May, and so were higher yielding than the traditional spring varieties.

By the 1970s, the country could have fed itself from home production, but then a rise in global trade meant that cereal food could be imported on the cheap. Home production became almost irrelevant to peoples’ consumption of cereal products except oats.

The seemingly unstoppable rise in grain yield slowed in the late 1980s. The brakes were on – for various reasons (which will be looked at another time). Yields per field and total grain output from the country have hardly changed since. They go up, as in the favourable weather of 2014, and down as in 2012 and 2018, but their present trajectory is level.

It’s the same for grain output in much of Europe, and crops farther afield, such as oil palm, also suffer: years of expansion and rise in output are followed by a levelling.

The levelling presents a major problem for science and crop management. 2014 gave the highest average yields ever in the region expressed as grain mass per unit field area. There is still potential for increase. The maximum on-farm yields are much higher than the average. Possibly modern varieties, able to yield well in good years, are over-sensitive to bad years.

The great swing in the mid-1900s from mostly oats to mostly barley was caused by markets and new opportunities for trade. Science and technology provided the means but the markets drove the change. Government strategy was to gain self-sufficiency in food, but that sufficiency ultimately came from outside.

There was no real strategic plan for home -grown production and there does not seem to be one now. That farming can switch between the three grains (and between grain and grass) should make agriculture less at risk of future catastrophe, whether due to climate. volcanic eruption or blockade. But the country should not wait to see what happens.

The resilience afforded by oats, barley and wheat should now be planned into the future of farming here. The Common Agricultural Policy did little to challenge current markets and the dominance of the few major influences. Post-CAP there is an opportunity to set targets for home-grown cereal food as distinct from cereals as substrates for animal feed and alcohol. Tinkering round the edges will do little. Major structural change in land use is needed.

Some previous posts on this web site have looked at the effects on crops of unusual weather in the past decade [2]. Future articles and notes will look at how farming used the three grains to the lessen the damage caused by the 2018 drought. We’ll also be starting a major series of articles on the options for future sustainability, with reference of course to lessons from the past 5000 years.

[1] A longer version of this article is available as on the curvedflatlands web site: Resilience in a three-grain production system, where full reference is given to the government statistical records from the late 1800s to the present and commentaries on trends in areas and yields of the three grains.

[2] Related topics on the Living Field web site: Winter flood on the water-field pages and The late autumn floods of 2012. For our general educational work on grains, see Ancient grains at the Living Field – 10 years on.

Author contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk, geoff.squire@outlook.com

[Last update: 16 March 2019, with several textual corrections! GS}

Sponsored by Dunkeld and Birnam Historical Society and the Dunkeld and Birnam Community Growing Group (The Field) at Birnam Arts, 23 November 2015, 7.30

A survey of crops and croplands – from domestication 10,000 years ago, through the arrival here of settled agriculture in the late stone age; through the developments of bronze and iron to the ill years of the 1600s; through the major improvements in the 1700s that gave hope; through the technology of the 1900s that eventually removed the threat of famine; to the subsequent choice between sustainability and exploitation, and society choosing the latter; to the present state of soil degradation and reliance on imports for food security; and to a sustainable future, perhaps … with some tales along the way of life and farming when horse was the quickest way along the A9.

More …

Settled agriculture is a recent experiment in human history. Domestication of crops from wild plants, as recently as 10,000 years ago, produced the wheat, barley, maize and rice that we know and eat today. Maize and potato were domesticated in the Americas and could not cross the Atlantic at that time and rice was too far away in Asia, but wheat, barley and oat came by land and sea across Europe to the north Atlantic seaboard where around 5000 years ago, they found a welcoming soil and a mild climate.

The grain crops enabled a settled society. In good years, there was food to last the winter, giving time to think and make things. Stability allowed people to learn the skill and enterprise to trade in the new technologies of bronze and iron that came across Europe centuries later. Waves of migration, Celts and Romans included, caused no great change to the basic type of grain and stock-farming of the region. A neolithic farmer, teleported here for the day, would recognise our crops and farm animals (except neeps and tatties which weren’t here in their day).

Yet time, ignorance and oppression took their toll: centuries of misuse, the principles of soil fertility unappreciated or ignored. Soils exhausted and yields dropping to subsistence levels. Agriculture unable to cope with the run of poor weather in the late 1600s? Starvation and famine.

Then came the age of improvement after 1700 – lime, fertiliser, turnips and other tuber crops, the levelling of the rigs, removal of stones, drainage, new machines for cultivation, sowing and harvest, the global search for guano, the coordinated management of crop and stock – benefits that allowed outputs to rise in the 1700s, but not yet to the point where famine was memory. That came later. It was not until the technological developments of the 1900s – industrially made and mined fertiliser, pesticides and advanced genetic types – that the threat of hunger was finally dispelled from north-west Europe.

But these same technologies opened the way for excess and instability. They encouraged the breaking of two established links that had held cropped agriculture since it began here.

The first was that grain and other crops no longer relied on grazing land or grass crops for manure. Grain could be grown more frequently, on more area and with more inputs – eventually encouraging a phase of intensification after 1950 that increased yield but in many places to the detriment of soil and the wider environment, and now with a diminishing return from inputs.

The second was that local production became separated from local consumption. The increasing wealth and global trade of the 1900s – the legacy of the industrial revolution – meant that people no longer relied for their subsistence on what was grown in local fields. This second decoupling became so great that by the 1990s, all cereal carbohydrate eaten in Scotland, except oat, was grown elsewhere and imported.

There are some big questions therefore. Will intensification continue to degrade soils and even start to drive down output? And is our food supply now too vulnerable to external influence – disruption by global terrorism, variation in world cereal harvests, future phosphate wars and volcanic eruption?

So what of the future! Yields are still high. Agriculture is diverse and diversifying in its margins. But threats to soil and food security will increase and need to be tackled. Technology alone will not solve the problems.

Geoff Squire

James Hutton Institute, Dundee UK

The speaker illustrated his talk with some ancient cereals and a bag of grain, all grown in the Living Field garden.

The quotations from Andrew Wight’s journals from his travels by horse are now available free online:

Wight, A. 1778-1784. Present State of Husbandry in Scotland. Extracted from Reports made to the Commissioners of the Annexed Estates, and published by their authority. Edinburgh: William Creesh. Vol I, Vol II, Vol III Part I, Vol III Part II, Vol IV part II, Volume IV Part II. All available online via Google Books.

His notes on bere, oat and flax in the region of Dunkeld and Birnam will appear in a later article on this web site. Any further enquiries: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk