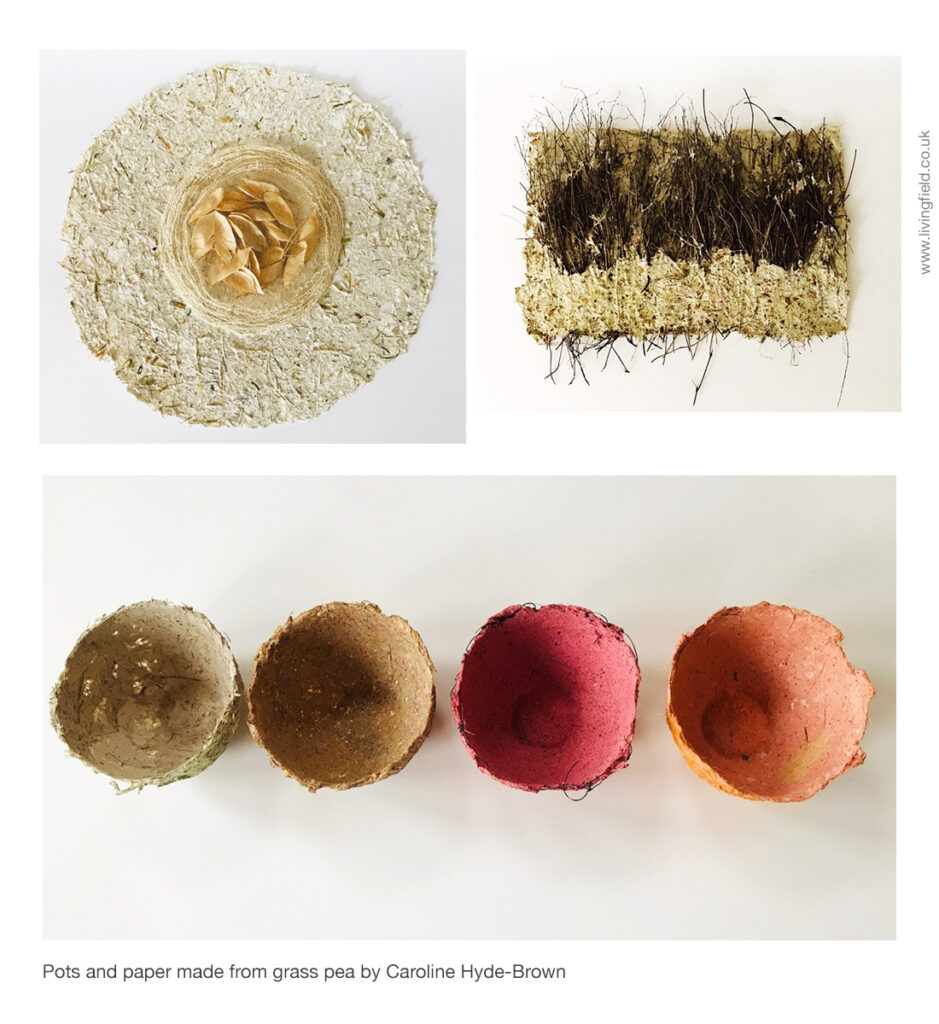

Caroline Hyde-Brown, at Norwich University of the Arts, gave the Living Field this account of her work with the legume, grass pea. Here are some examples of her craft.

Read on to see how it is done.

Introduction to the grass pea

The grass pea Lathyrus sativus is a member of the legume family (Fabaceae) and commonly grown for human consumption and livestock feed in Asia and East Africa (Caroline writes). It is a hardy yet under-utilised crop and able to withstand extreme environments from drought to flooding. The grass pea fixes nitrogen from the air which helps maintain a healthy and well fertilised topsoil [1].

However, the grass pea contains a potent neurotoxin called B-ODAP which increases if the plant is exposed to conditions of severe water stress. Historically the grass pea is known to produce adverse side effects with excessive human consumption which exacerbates the risk of a neurological disorder known as lathyrism which can cause permanent paralysis below the knees both in adults and children.

Growing the plants

In September 2019 I initiated a collaboration with John Innes Research Centre in Norwich to investigate whether this ancient legume could be utilised to create a biomaterial with a sustainability strategy of raising its residual value. With a mixed methodology of qualitative research, critical inquiry, and home-based experimentation, I explored the inherent qualities of the natural raw plant residue with Anne Edwards and Abhimanyu Sarkar [2]. I used a framework known as the ‘whole systems’ approach adding freshly collected rainwater and solar heat [3].

I experimented with different types of potting containers to observe growth patterns and plant behaviour. Shallow containers produced spindly and weak plants compared to the much stronger and higher yielding plants grown in deep ‘rose’ containers or in a glasshouse.

My assistance with the harvest at John Innes yielded positive results during January 2020. I began with behavioural growth studies in agar flasks, which provided a fascinating insight into the delicate root structure as the roots are normally below ground. Unexpected discoveries about how the grass pea behaved under certain conditions helped the iterative design process.

During lockdown last year I had time to observe the plants on my windowsill and how they used the agar provided by John Innes. I didn’t need to water them, and it was fascinating to see how the plant easily grew, the perfect house plant!

I also planted some grass pea in different types of container with various depths to see which environment the crop preferred. The black container (photographs above, lower left) provided the wonderful patterned shapes shown lower right.

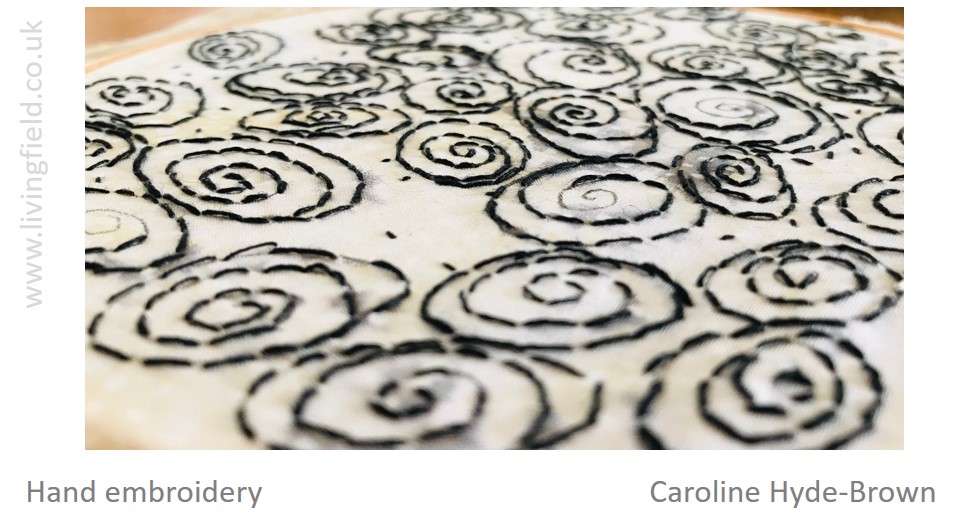

Embroidery with roots and tendrils

Perfectly formed tendrils from the harvested residue of grass pea inspired me to do some hand embroidery. I used Kantha stitching on cotton to reflect the Indian traditional embroidery technique of simple straight stitch.

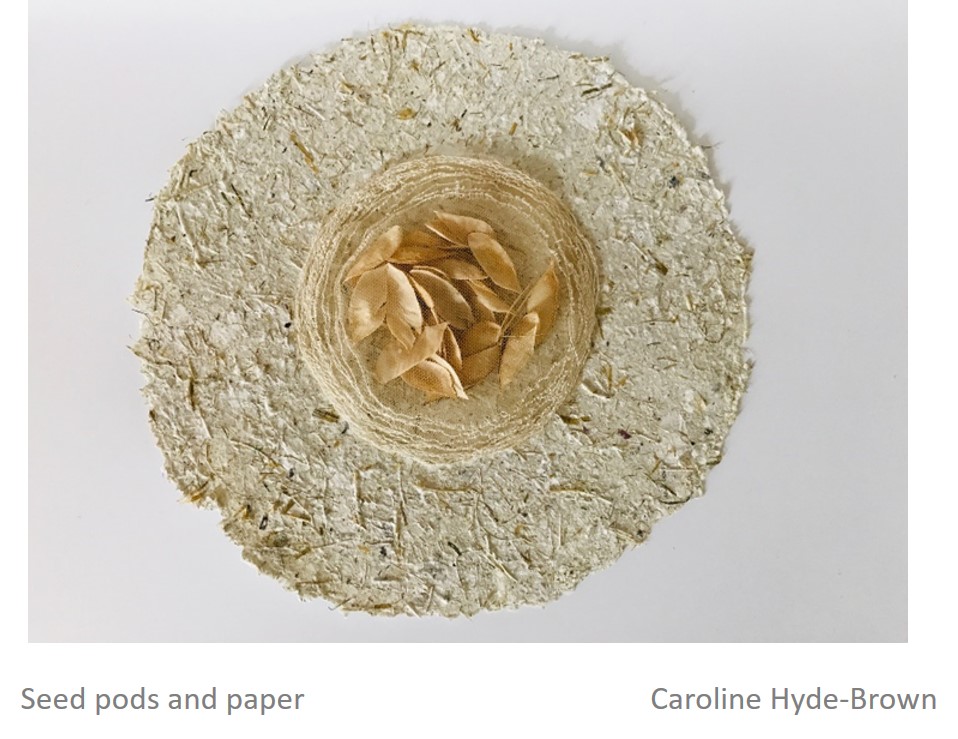

My overall aim was to see whether the grass pea residue could be recreated into a cloth of some kind. Cutting up the paper samplers and using other threads and vintage lace slowly transformed the paper into a fabric, but the harvested residue was extremely dry and brittle.

I was unable to spin a thread out of the stalks. However, I believe, with the right biotechnology, cellulose could be extracted from the grass pea to make clothing, paper, shoes and lighting. Recent advances prove that using agricultural waste is an extremely profitable and sustainable operation with companies such as Agraloop [4], already spinning innovative and unique fibres.

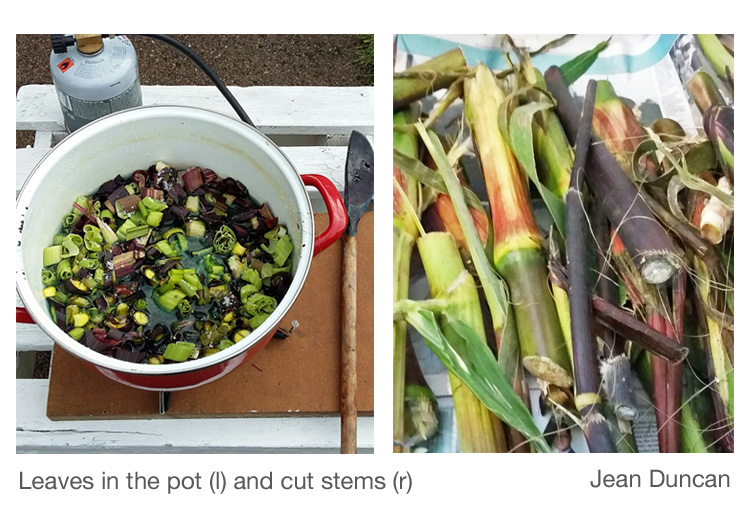

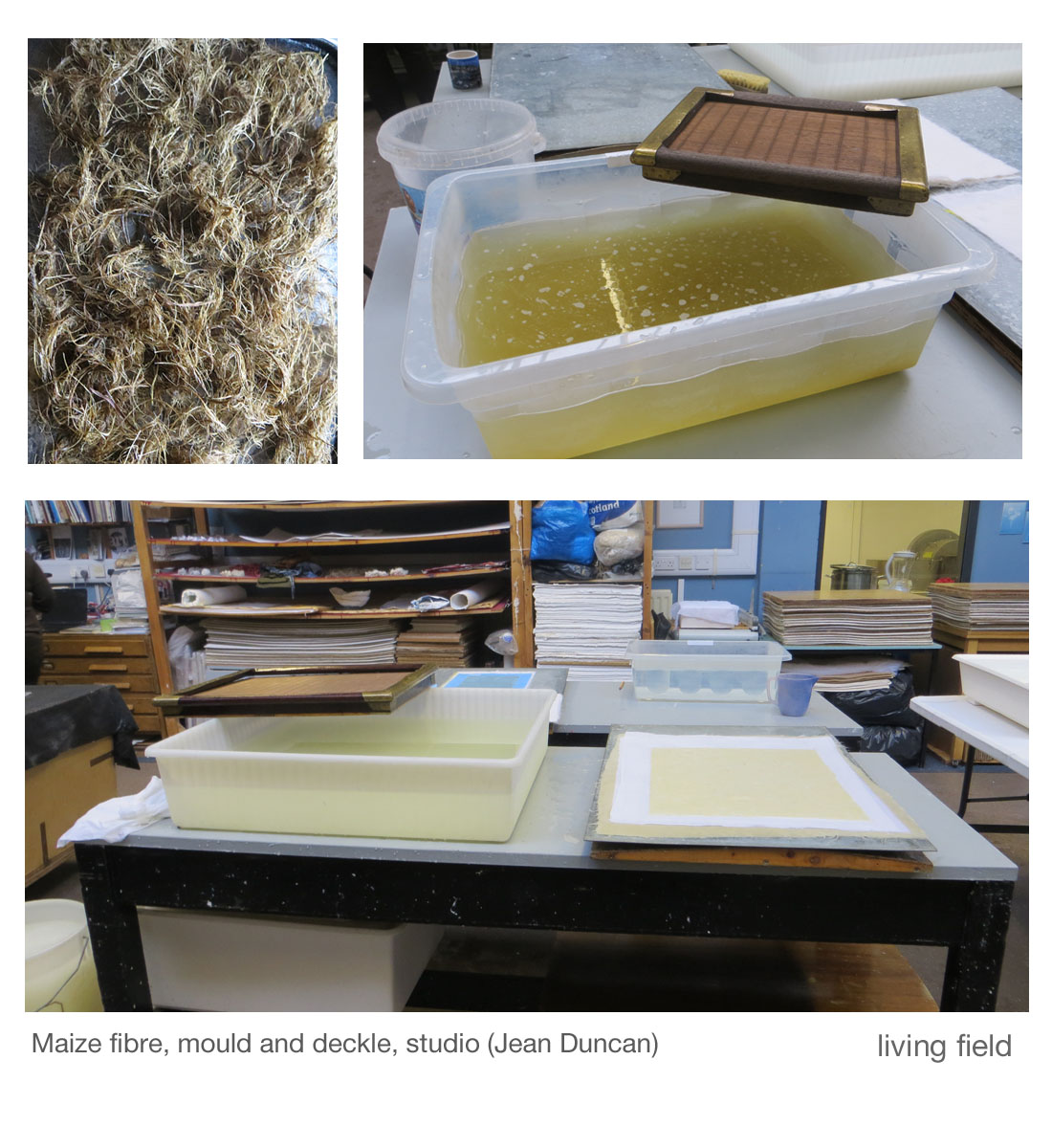

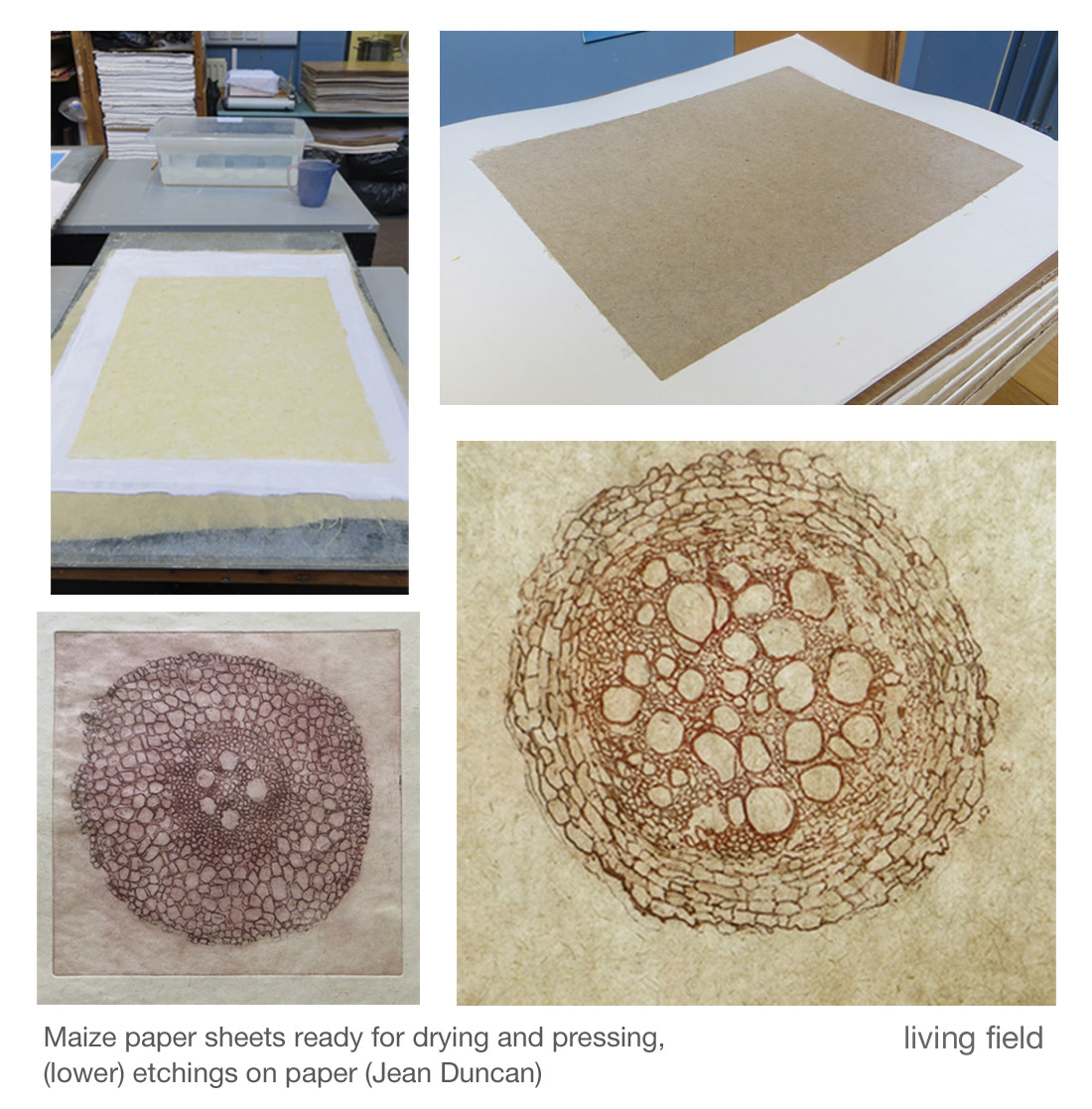

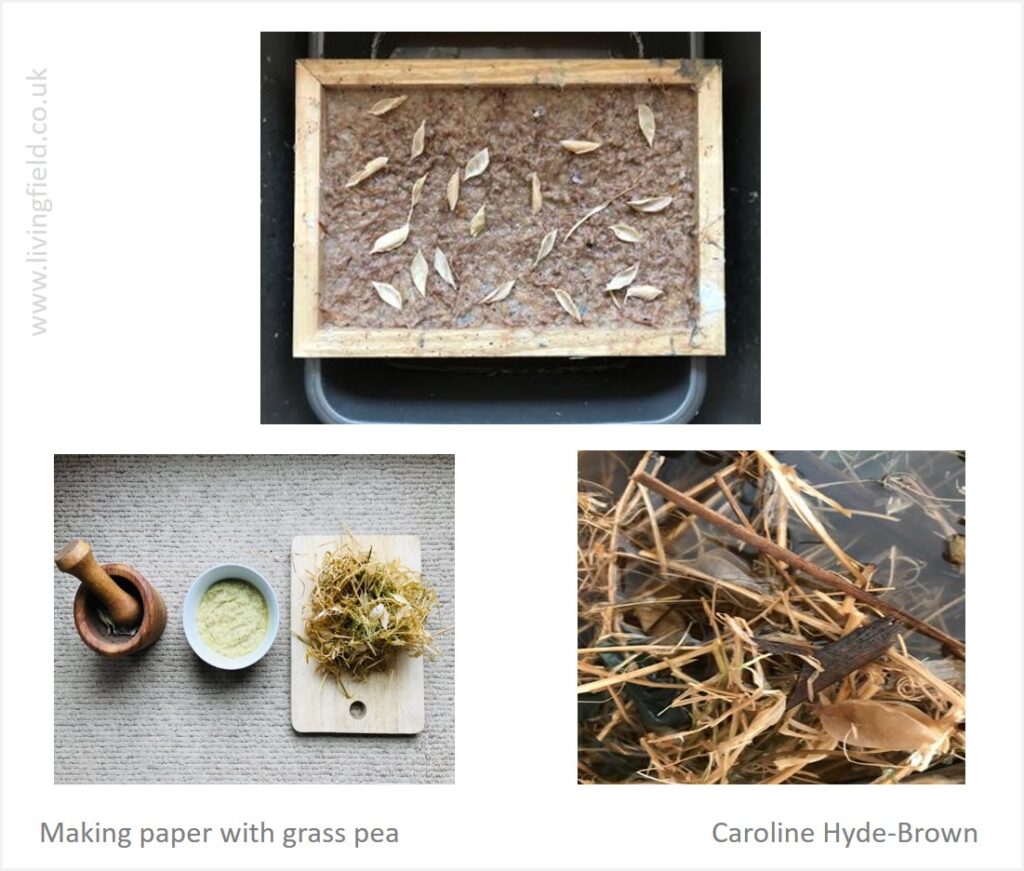

Papermaking

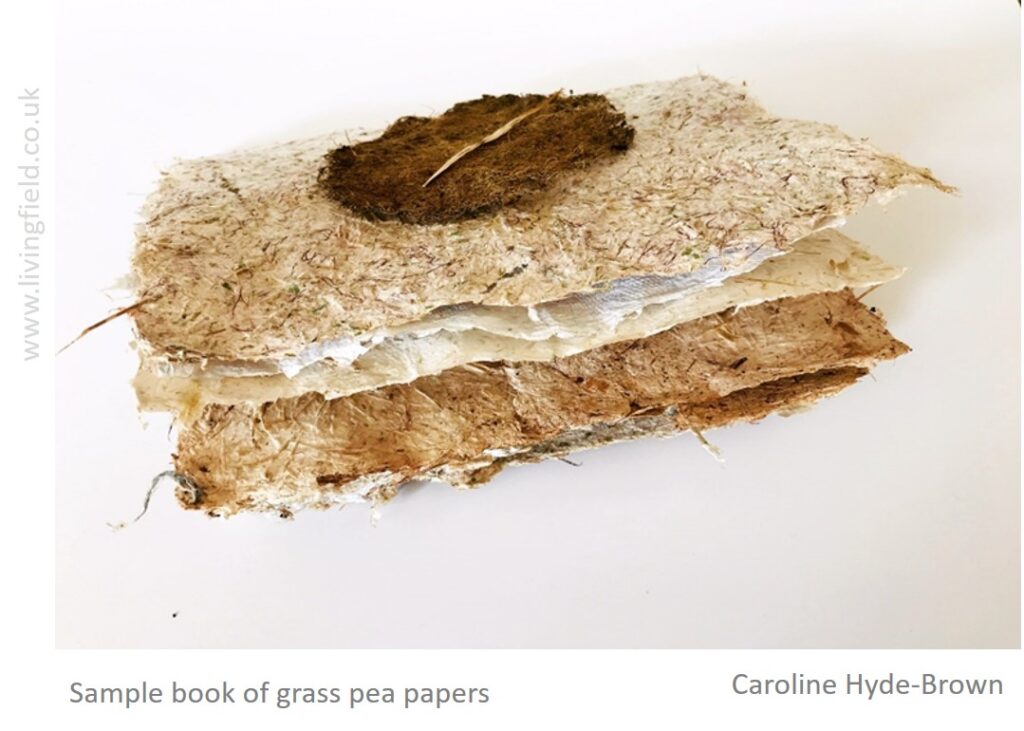

Initially my papermaking explorations were unsatisfactory. The handmade paper felt stiff, broke easily and resembled cardboard. After boiling the residue and retting it in a bucket for a week however, it softened to produce a softer slurry or pulp.

Although I was unable to provide precise samples of artisanal stationery, each piece of handmade paper had its own individual character. I began to realise that imperfections can help create an authentic narrative and felt more confident in exploring other possibilities with ingredients.

A series of handmade papers were constructed from localised resources. I wanted to see if the grass pea could hold other grasses and petals within multiple layers of slurry. I took advantage of the warm weather and dried them in the garden. By adding spices from the kitchen, combined with grass clippings and petals taken from hedgerows and heathers they took on a lovely range of colours.

I also wanted to test some of the bio-resins from my collection of azeleas to see whether it added another material dimension. I looked at adding colour and referenced the pantone colour range for 2020 to provide inspiration for a moodboard of handmade paper.

Bio pots and other functional products

Interpreting scientific knowledge and merging it with my own craft-oriented methods is a lengthy and complicated process. The bio pots initially started out as a conversation when I decided to see whether the knowledge I had gained through papermaking over the summer could result in something more tangible like a functional product.

I looked at whether the grass pea pots could be dyed to provide colour, starting with kitchen spices such as paprika and herbal tea bags with raspberry, blueberry, tea, and coffee. These were quite successful samples and ongoing observations are being made into the waterproofing and durability. Further growth studies will commence this year with a view to creating something that may offer a sustainable alternative for the tree planting initiatives overseas.

… and some final remarks

Research into the use of natural resources to provide extra sources of income has proven potential. It shows how the bridging of traditional artisan work with modern design can provide sustainable solutions. An essential part of the process includes rigorous testing of raw materials to demonstrate that the process is both restorative and circular from the beginning of the supply chain to the end product.

As an inter-disciplinary artist, I seek to implement new ideas through forming partnerships which help shape and question my own practice. I feel fortunate that we could build a strong professional network to bridge knowledge gaps. It was a collaborative process that reinforced our objective of helping to improve rural livelihoods in India.

I conclude that the grass pea supply chain could be disrupted from field to biomaterial and repurposed to provide vital ingredients for economic change.

Sources | Links

[1] Caroline writes: “When all other crops fail, grass pea will often be the last one left standing. It is easy to cultivate and is tasty and high in nutritious protein, which makes it a popular crop. The Consultative Group on International Agriculture Research (CGIAR) states that at least 100,000 people in developing countries are believed to suffer from paralysis caused by the neurotoxin. More at the Crop Wild Relatives Project: The curious case of the grasspea.

[2] From the John Innes Centre web site, 27 May 2020: Paper making with grass pea.

[3] The “whole systems approach” was devised by a group of Product Design Students at the Iceland Academy of Arts in 2015 during a project using willow. They designed a unique range of products including paper, glue and string adding just heat and water.

[4] Agraloop: transforming low-value waste to high-value fibre.

[5] The Journal of Sustainability Education describes how collaborations beyond the comfort zone of specialist areas possibly hold the key to making unusual discoveries. Journal web site: http://www.journalofsustainabilityeducation.org/

Contact Caroline Hyde-Brown

email: artistcaz@aol.com

web site: https://www.theartofembroidery.co.uk/

The editor writes: Many thanks Caroline from the Living Field for sharing your experiences and experiments on grass pea. We hope you can continue to develop the technology and craft work and help to generate new income streams for growers.

For other occasional Living Field articles on the use of legumes, see Feel the pulse and Scofu: the quest for an indigenous Scottish tofu.