Natural dyes in history; wild harvesting; growing plant dyes as crops; tinctoria and officinalis; the absence today of dyes as crops; prospects for natural dyes in craft-scale production.

[Latest update – 25 February 2022]

The past – history of plant dyes

Throughout the history of useful plants, there had never been an absolute distinction between harvesting plants from the wild and sowing seeds in tilled fields as crops. Many useful plants would have been conserved or encouraged where they grew naturally. Many dye plants are of this type.

Sometimes, nurturing useful plants needed nothing more than clearing away other vegetation or disturbing soil to allow seed to germinate. Seed or vegetative parts would also have been carried around and planted as people moved from place to place. Even after settled agriculture arrived here, harvesting of wild plants continued.

Of the plants extracted for dyes here, most have been harvested from the wild. Other than woad and weld, also madder in the south of Britain, few have ever been managed in the croplands’ fields.

Dye plants as crops

Perhaps the most widely known of the dye plants that can grow in our climate are woad, weld and madder, yielding blue, yellow and red colourings. The centres for production of all three in Britain were in the Midlands or south of England. The Edinburgh seed merchants Lawson and Son wrote in 1852 that there were few dye plant species other than these grown commercially in Britain at that time.

There is little in the archaeological or historical records on whether dye plants were grown as crops. Weld was present in Medieval Aberdeen, Perth and Elgin, while woad was imported for centuries and grown here in the 1800s (Dickson & Dickson).

The history of the growing, import and use of these and other more exotic dyes shows time and again that early agriculturists and manufacturers were well connected by trade with many other countries. Thirsk describes the remarkable story of the attempts since medieval times to make commercial field crops from these plants.

The later 1900s, and the 2000s so far, are devoid of dyes as crops.

Woad

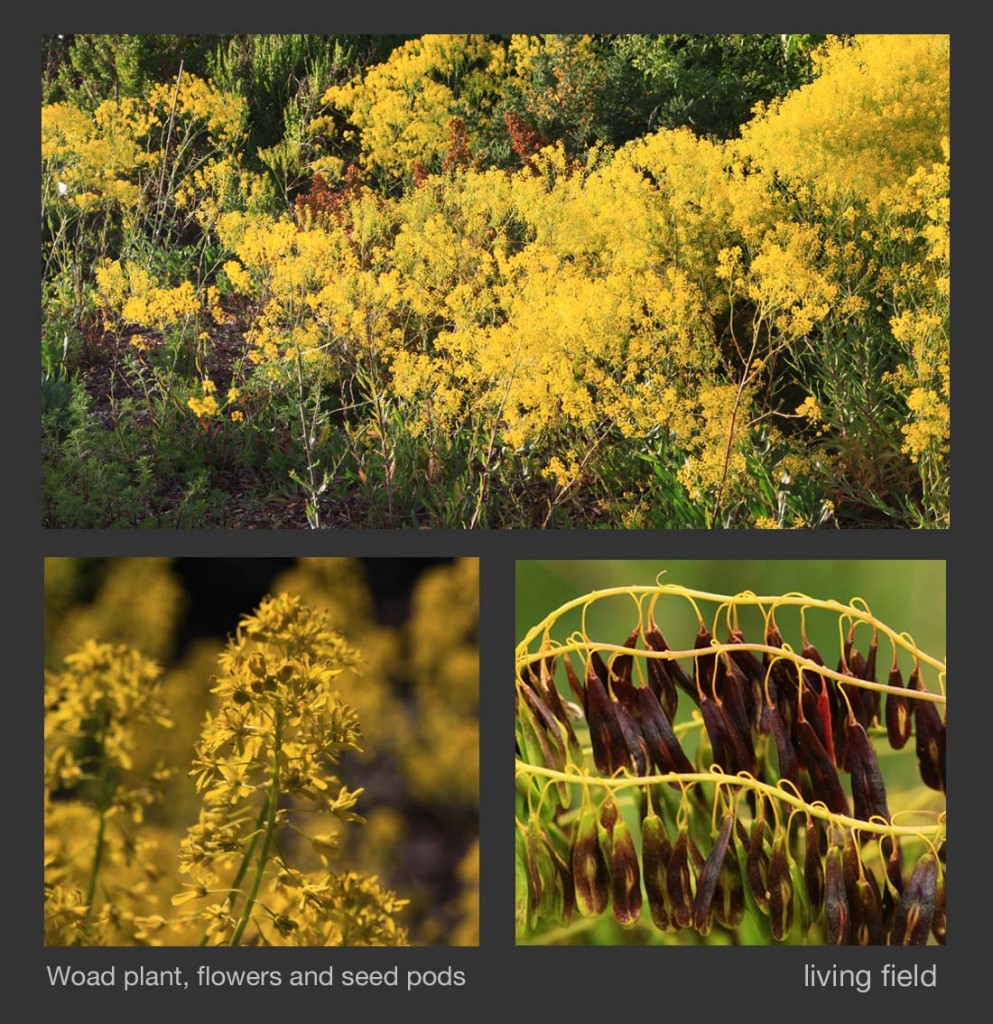

The blue dye from woad Isatis tinctoria is taken from the leaves at the base of the plant. Sown in August, the basal leaves are harvested the next year, then allowed to grow and and are re-harvested several times.

Grigson and Dickson & Dickson point to the lack of evidence for the use of woad in ancient times, even by the Celts in Iron Age Britain and the Picts more recently. It had been imported as a cloth dye for centuries before it began to be developed as an industrial crop from the 1600s, until (as Grigson says) ‘the nineteen-thirties, when the two remaining woad-mills in Lincolnshire – the only two left in the world – were closed.’ Competition from the imported indigo was the cause.

In the 1800s, Lawson & Son stated that ‘woad was formerly cultivated to a pretty considerable extent in Scotland’. Attempts to revive woad as a crop have continued up to the present but without lasting success. Woad is yet another of that most useful group of plants, the cabbage family (Brassicaceae, formerly Cruciferae). It appears occasionally as a feral plant, but very rarely so in the north.

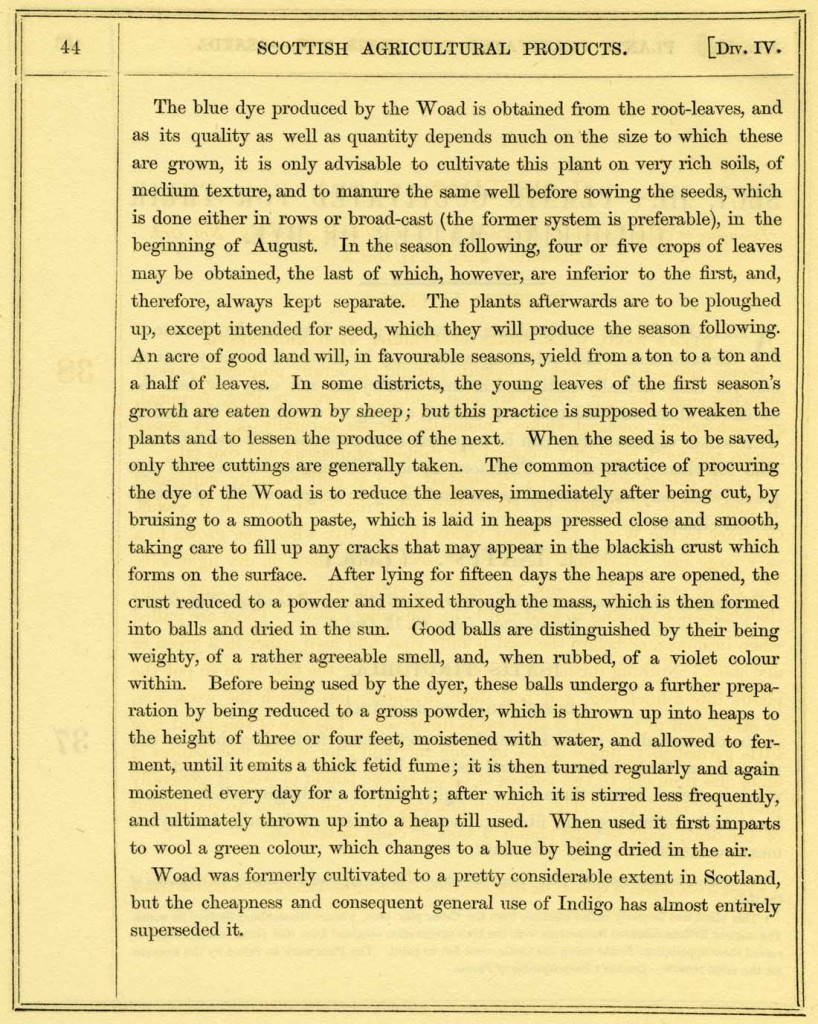

The procedure of preparing woad leaves was lengthy and complicated, as described in the scan above of a page on woad from Lawson and Son (1852) . The words can be read under higher magnification.

Weld

Weld Reseda luteola, a native plant, is the only one of the three to grow wild locally. Its foliage is harvested to give a yellow dye. It has been found in Stone Age sites, though not in Britain.

It was grown as a crop, mostly in the south and east of England, and sometimes sown with barley and oats, to be harvested the year after and the seed kept for the next crop (Grigson, Thirsk). Likewise, ‘the usual practice is to sown the seeds in spring along with a corn crop; the plants not running to seed until the following season’ (Lawson).

The plants are pulled in flower and used green or dried. Leaves and stems are put in a linen bag and boiled in water ‘into which the wool, silk or other stuff to be dyed is afterwards immersed’.

Docklands, old industrial sites, airport runways and wasteland provide a refuge for weld today. The panel below shows its habitat in the cobbled walkways at Dundee docks, and middle right the dried stems, and lower right wool dyed with weld.

Madder

The madder most widely used as a dye is not the field madder Sherardia arvensis or the wild madder Rubia peregrina, which itself yields a pinkish dye, but the perennial Rubia tinctorum from central Asia. It is a relative of the weed cleavers Galium aparine and lady’s bedstraw, itself yielding a dye.

Madder, also known as Turkey Red, is extracted from its roots, which when lifted in the third season are kiln dried, chopped and ground. Several web-links in Sources … tell the industrial story of the much sought and much valued Turkey Red.

Madder seems to have been first grown more for medicinal use – noted in Norfolk in 1274 – than as a dye, but its development as an industrial crop from the 1600s had a turbulent history, as Thisk relates, until the crop receded following artificial manufacture of the dye in 1869. Lawson & Son (1852) related that ‘its cultivation in this country has been almost if not entirely abandoned’.

Spontaneous combustion!

A short note in a periodical named the Belfast Monthly Magazine (Vol 10, number 55, Feb 28 1813, p. 127):

‘The frequent accidents by fire in manufactories, have excited the attention of scientific men …. (and) …. a multitude of substances are capable of spontaneous inflammation… ‘.

Among the list of offending materials are candle-wick of hemp-yarn, accidentally impregnated with oil; cotton goods on which linseed-oil has been spilled; wet hay, corn and madder; sail-cloth smeared with oil and ochre; vegetables boiled in oil or fat and left to themselves after being pressed; paint made of Derbyshire woad. Dangerous stuff, these dyes and fibres!

Tinctoria and officinalis

Many of the dye plants have the botanical name ‘tinctoria’ or ‘tinctorum’ (from tinctor, a dyer in Latin). Others share the specific ‘officinalis’ with herbs and medicinals. Stern (1966) writes that ‘officinalis’ is derived from the Latin for ‘workshop or shop, later a monastic storeroom, then a herb-store, pharmacy or drug-shop.’ Some plants were used both for medicines and dyes.

Dye plants in the garden

While few dye plants were grown as crops, they nevertheless found a quiet, cultivated haven in the monastery garden, the small allotment and the vegetable patch.

Rhubarb, for example, is not only one of the most delicious and uncomplicated ‘fruit’ puddings but its rooty material, when boiled, yields a strong yellow-orange colour. Tansy Tanacetum vulgare is both a wild plant and garden plant whose flowers give a yellow colour.

Dyer’s chamomile and dyer’s coreopsis Coreopsis tinctoria are mostly garden plants in the north and give various oranges and yellows (images above).

Most of the wild or free growing dye plants used in Britain can be cultivated in the garden.. The wild plants shown below have, except for white water lily, been grown in the Living Field garden for many years.

Present use and prospects for dye plants

As for fibres, there is now no commercial growing of dye plants as farm crops. We can only imagine a field of corn – barley and oats – grown along with weld which will be left in the ground until the next season when it would be harvested. Or a field of woad, sown late in the year, to overwinter and be harvested next year – how did it look among the fields or rigs of corn and turnips?

That is not to say the interest in natural dyes has disappeared. The knowledge and expertise of wild dye plants is kept alive in craft work, especially where the dyes are used to colour wool from native or rare breeds of sheep.

Links are given in Sources … to workshops and web sites that supply seed and demonstrate how to extract and use plant dyes.

Dye plants are found in a range of habitats where they contribute to the storage of carbon and nutrients and the movement of these elements through food webs. That the plants contain dyestuffs has usually little relevance for their ecological function, unless they have been sustainably (or unsustainably) nurtured or harvested at a scale that affects the habitat.

The legumes figure here, just as they do in the tropics. Gorse or whin Ulex europaeus and the brooms, notably dyer’s greenweed Genista tinctoria, usually grow in resource-poor soils, where they fix atmospheric nitrogen into root nodules, first for their own growth, and in time, for the plants around them. While gorse is common and widespread, the greenweed is now rare in the north.

Among the dyes (and fibres), the stinging nettle Urtica dioica is the most common and widespread, inhabiting woods, field margins and waste places almost everywhere except high ground.

Boggy land has its share of dye plants, yellow iris and bog ashphodel among them, while whin, lady’s bedstraw and tansy go for dry or stony grassland. Dulse and other seaweeds occupy the intertidal while the many lichen dyes live on rocks and trees. Dye plants everywhere!

Back to …… main Dyes page, Sources references links contacts.