By Russ Clare

Being the first part of an article by singer and musician Russ Clare on a song about grain crops and their importance in the folk tradition.

History of a song

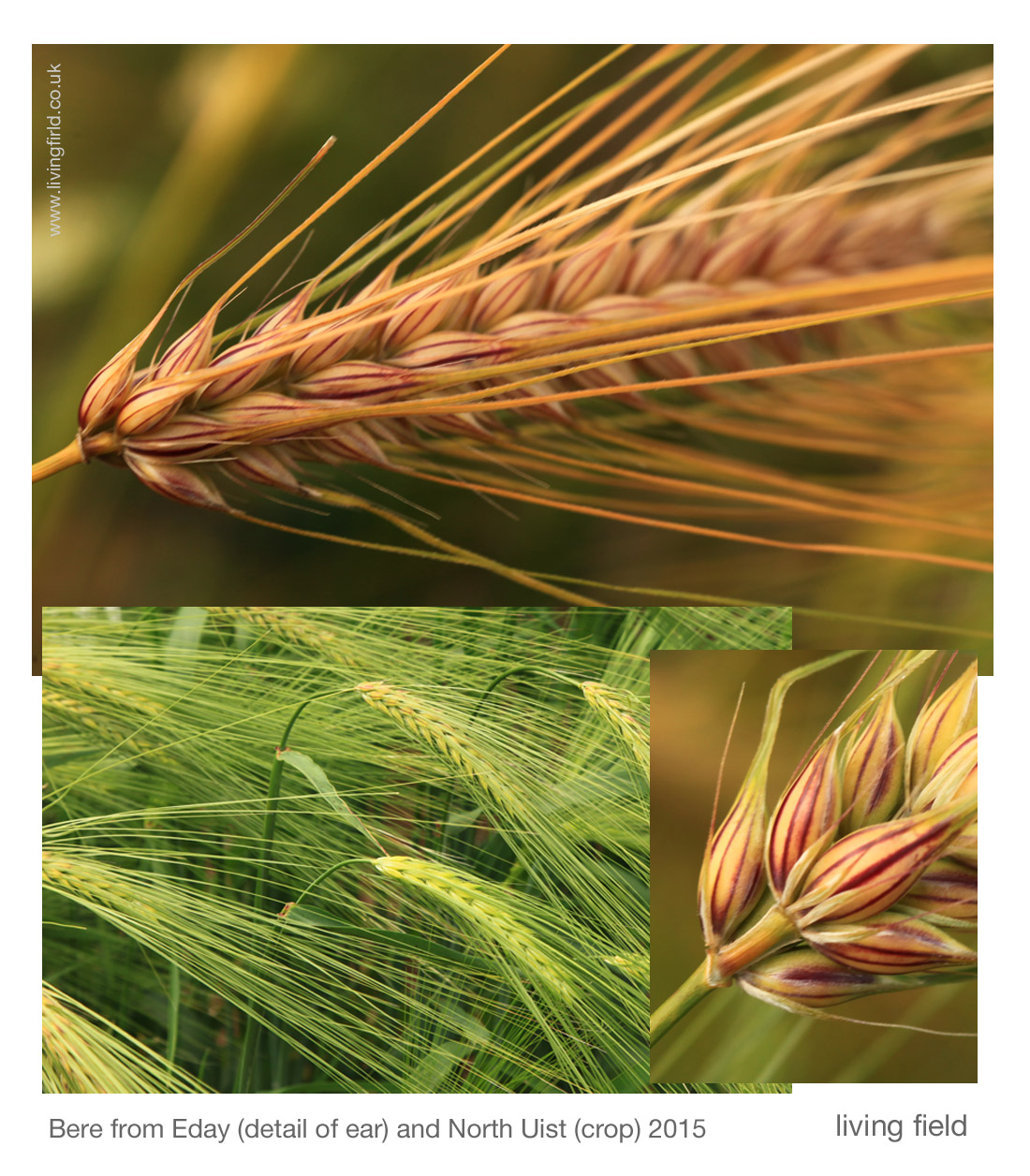

The corpus of rural England’s traditional balladry is admired for its engaging stories from the past still relevant today, and beautiful melodies often with a quirkiness towards time signature and modality. It’s a treasure-trove for singers. One such that I love to sing is All among the barley, also commonly known as The Ripe and Bearded Barley:

Come out, it's now September, the Hunters' moon's begun And through the wheaten stubble is heard the frequent gun The leaves are turning yellow, and fading into red While the ripe and bearded barley is hanging down his head Chorus: All among the barley, who would not be blythe? When the ripe and bearded barley is smiling on the scythe The wheat is like a rich man, he's sleek and well-to-do The oats are like the young girls, they're thin and dancing too The rye is like a miser, all sulky, lean and small While the ripe and bearded barley is the monarch of them all The Spring is like a fair maid that does not know her mind The Summer is a tyrant of most ungrateful kind But the Autumn is an old friend who pleases all she can Brings the ripe and bearded barley to gladden the hearts of man

I came across this little folk song gem in 1974 while browsing a poetry anthology in a Nottingham school library. My attention was captured by its portrayal of the changing seasons, setting the scene for a playful imagination of cereal crops and with special praise for barley, the brewers and distillers source of alcohol. I fondly imagined the song to have had a life in the past among the country people of rural Leicestershire, where I was living at the time. A likely favourite at harvest homes, those end of harvest celebrations of feasting, drinking, and singing. While All among the barley deserved a place in my growing repertoire for singing in folk song clubs, in this case no tune was given, merely a credit to Folk Songs of the Upper Thames. I had been unaware of the collection, and in those pre-internet times further enquiry soon came to a halt. So the hunt was on for a suitable melody.

The search ended with a dance tune, The Tip Top Polka, a personal ‘ear worm’ from listening to the brass band accompaniment for the Britannia Coconut Dancers on their Easter Saturday procession around Bacup, their home town in Lancashire. My mind attached All among the barley‘s words to the melody. It seemed a near perfect fit, and I have stuck with it ever-since, giving the song an airing each Autumn. Listen to a recording here.

All Among the Barley – a novel by Melissa Harrison

It’s likely I had the song in mind when, in September 2018, I noticed an intriguing newspaper review of All Among the Barley, a novel by Melissa Harrison. It is set in Suffolk in the 1930s, where local fourteen year old Edie meets Constance, a London writer on a mission (ostensibly) to chronicle the traditions of an isolated rural community challenged by modernity.

Harrison has garnered much critical acclaim for her evocation of a way of life in decline – the closeness and beauty of nature, more bountiful and diverse than now; age-old patterns of work driven by the seasons; the tension created from clinging to the familiar while recognising the need to embrace innovation. In a closing scene, following the story’s tragic conclusion, Edie’s grandfather sings to her. She is comforted by his songs, recognising the continuity they represent in the history of her family and home; songs passed down the generations.

In fiction, Edie heard her grandfather sing All Among the Barley. But the song has a real-life story of its own, about its origin and popularity, and its telling needs first a consideration of the nature of traditional folk song.

The song collectors

We will be forever in debt to Victorian and Edwardian song collectors for their rescue of so much of our traditional folk heritage, seemingly heading for extinction as singers aged and their art succumbed to rural depopulation, urbanisation and popular entertainment in the music halls. Between 1890 and 1920, Cecil Sharp, Lucy Broadwood, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Frank Kidson, and Percy Grainger, notable among others, wrote down thousands of song lyrics and tunes from country people, travelling widely, often by bicycle, in their search for singers. Sharp, in particular, was driven by an ideological attempt to use folk song as a resource to establish a National music with an identifiable English style; Vaughan Williams, though less ideological was arguably more successful in that pursuit.

In his essay, English Folk Song: Some Conclusions (1907), Sharp promoted the idea of anonymous community authorship of songs and their subsequent adaptation as they were passed around and down generations in a purely oral manner. It is unlikely, however, an oral tradition can survive exclusively alongside written communication – a degree of coexistence is more likely.

A community’s songs must be either composed from within, learned by listening to other singers or obtained from printed sources: the relative importance of these routes is keenly debated. Songs on commercially produced broadsides and chapbooks – written by artisan scribes or purloined from other sources – were commonly sold on the street from the 16th century. They were very popular, for it is a myth, although a popular notion, that illiteracy among the rural working class was widespread before 1700 and beyond. The work of folk song scholar, Steve Gardham, does support the idea that many songs, if not most, entered the tradition from these written sources. His analysis of 705 songs found in oral tradition in England between 1840 and 1940 showed 88% had their earliest extant version in some form of urban commercial production (Traditional Song Forum online address September 2020, from 47:50). It is, however, widely accepted, as Sharp first suggested, an oral process that turns a song from whatever source into a traditional folk song. Shared in a community by listening and learning, songs have been adapted and shaped by singers’ inherent creative talent and passed on to succeeding generations, thus accounting for the rich lyrical and musical variation found by collectors.

Origins of a song

So what of the origins and traditional status of All Among the Barley?

The earliest record of it is a composition by Elizabeth Stirling, published in 1851 as a four part (SATB) choral arrangement in Novello’s Part Song Book. Stirling (1819 – 1895), a career church organist and composer who studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London, enigmatically credits the lyrics to A T who has never been identified. Speculation among music scholars that it might be Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809 – 1892) is not backed by hard evidence, but they were contemporaries and both living in London in the 1840s, so a song writing partnership is not inconceivable. Moreover, in the opening verses of the The Lady of Shalott (1832), there is some resonance with All Among the Barley‘s lyrics:

On either side the river lie Long fields of barley and of rye... ....... Underneath the bearded barley, The reaper, reaping late and early....

An indication of a common author, or mere coincidence?

A song spreads far and wide

A judging panel of Novella’s collection awarded 2nd prize to All Among the Barley, and, among Stirling’s various organ compositions and song arrangements, it was, and remains Stirling’s most popular work, for which the sheet music is still available. It soon became a frequent choice for amateur choirs, as in the inaugural concert of Weymouth Choral Society on February 26th, 1862, and a concert given by Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam) Glee and Madrigal Club on 17 March 1879.

Writing in English Dance and Song magazine in 1967, Tony Wales cites several sources indicating the song’s popularity in schools well into the 20th Century. All Among the Barley soon found its way to publishers of songbooks such as The Fashionable Songbook (Routledge, 1865) and of broadsides across the country, including J Harkness of Preston in (1874) among many.

Stirling’s song also became popular in the USA; the Library of Congress records an arrangement in three parts for women’s voices (Lee & Walker, Philadelphia, 1871), and a version with a message from the Women’s Temperance Society in Living Waters—A Collection of Popular Temperance Songs, Choruses, Quartets (Peters, J. L., New York, 1874):

All among the Barley, wander you and I Tho' we love the smiling Barley, we shun the dreadful Rye Tho' we love the happy Barley, we shun the dreadful Rye

It was also included in resources for schools, as in The Golden Robin (W.O. Perkins, Boston 1863).

A popular song in print, then, and the work of a musician and, perhaps, a lyricist too, who were some steps removed from its bucolic setting. Instances of the song in oral tradition are surprisingly sparse, however. Among a plethora of printed sources, Steve Roud’s eponymous Folk Song Index cites All Among the Barley for nine singers, eight with records made between 1914 and 1974 (a ninth is undated). So, an enduring circulation among country singers in 20th Century England is suggested, and all evidence is consistent with All Among the Barley entering the tradition from written sources traceable to Sterling’s original score.

One song collector and one singer deserve more attention

Alfred Williams (1877 – 1930) collected folk songs from the Upper Thames Valley in Gloucestershire, Wiltshire and Oxfordshire. In contrast to Sharp and other materially comfortable, middle class collectors, Williams was born into working class poverty – in the village of South Marston, near Swindon. He was a half-time farmhand at eight, full-time by eleven, and a Swindon railway factory worker for 23 years. Williams was, nevertheless, an effective autodidact. Rising early to work before a factory shift and resuming late into the night, he published several volumes of poetry and social history, drawing on a love for his native Wiltshire countryside, and a commitment to recording the local people’s way of life. Along the way he found time to learn several languages, including French, Latin, Greek and Sanskrit. His most enduring work, Life in a Railway Factory documented the drudgery that led to his health break down and reliance on writing for a living.

Between 1914 and 1916, Williams cycled thousands of miles collecting the words of nearly 800 songs; a selection of some 200 were published as Folk Songs of the Upper Thames in 1923 “The greater part of the work of collecting the songs must be done at night, and winter is the best time, as the men are then free from their labours after tea.” On one such cold, night time journey Williams collected The Ripe and Bearded Barley from Henry Sirman, a farm hand of Stanton Harcourt. Williams lacked the skills to note down tunes, but the songs’musicality was not his prime concern; he was more interested in the significance of the songs in the lives of his informants. His own life was tragically short, worn down by poverty and a punishing work schedule.

To its considerable surprise and delight, the folk music scene of the 1970s discovered a traditional singer living, and hiding in plain sight, in Norfolk. Walter Pardon (1914 – 1996), a carpenter, passed his entire life, apart from four years war service at Aldershot, in the village of Knapton. He had a repertoire of around 150 songs, mainly learned by listening to family members. As a younger man there were few opportunities for social singing or public performance so he sang for his own entertainment, continuing in the isolation of the family cottage long after both parents had died.

Walter’s cousin Roger Dixon, a history teacher, aware of the interest Walter’s singing would arouse, recorded 20 songs and passed the tape to professional folk singer, Peter Bellmay. A late flowering singing career followed for Walter, who performed at clubs and festivals, recorded several CD albums, and sang in Washington at the USA’s 1976 bi-centennial celebrations, before retirement at 75 in 1989. His repertoire is notable for having several exclusive or rarely collected songs, including All Among the Barley. Sung to an approximation of Stirling’s tune, it can be found on Walter’s CD Put a bit of Powder on it, Father and in The British Library Sound Archive.

All Among the Barley has retained its appeal. In the 1980s Cheltenham singers, Mike and Jackie Gabriel, had the lyrics but no tune so composed their own. Robust, invitingly singable, and very much in an English traditional style, it has become, almost, the exclusive melody of choice for today’s singers. Several interpretations can be found on Youtube and variation in words and music shows the ‘folk process’ still at work.

The second part of Russ Clare’s article Social and environmental changes during the life of a song will be published later on this web site.

Contact: http://www.russclare.com/

Ed: many thanks to Russ for this contribution on the enduring presence of grain crops in folk traditions.