The Living Field has supported local crop landraces and traditional varieties. We have grown them, saved their seed, used their products to make food, promoted them on open days and shared them with growers and gardeners.

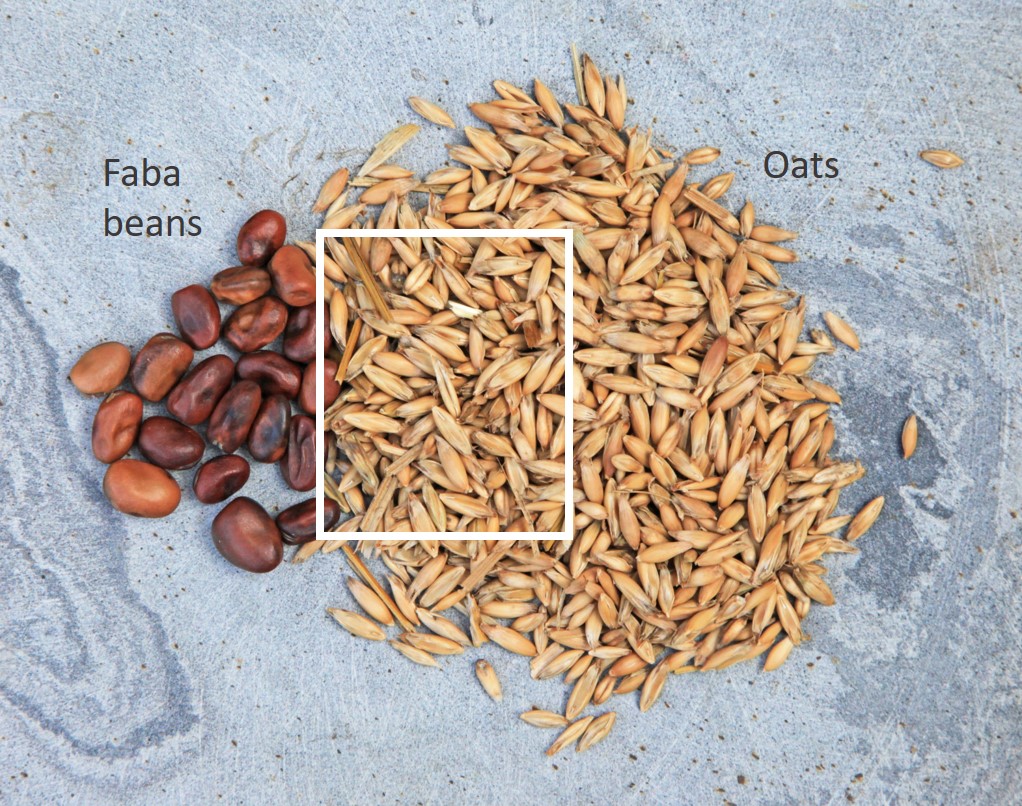

Grains are the staple diet of any settled population. Neolithic ancestors brought them to these islands thousands of years ago. People have sustained themselves on locally grown grain crops such as oats, wheat and barley and di so in Scotland through the 1800s.

Today, most grain grown in Scotland is used for livestock feed and malting (alcohol). Apart from oats, which occupies a small area of arable land, and a few fields of special barley and wheat, the cereals people eat are grown elsewhere and imported as products of wheat, pasta, rice and maize. Of these, the UK as a whole is close to sufficiency in wheat – for bread, biscuits, cakes, and similar – but the once-close links between growing and eating grain have been severed. [Ed: this paragraph revised 4 April 2022].

So it is specially good to hear the continued and growing interest in projects like Common Grains [1] and Seed Sovereignty [2]. They operate outside the conventional channels of crop varietal breeding and depend on local and often unfunded commitment for their success. Here we pass on some recent news and upcoming events from both projects – with images of the Living Field‘s cereal landraces and some old methods of grinding and milling grain.

Common grains

With emphasis on both growing and baking, Common Grains is showing that short food chains work. It aims to reduce the physical and commercial distance between seed, crop, harvest, (saved seed), processing, baking and eating. As a result, the eater will likely appreciate the growing and have an vested interest in soil health and biodiversity .

Common Grains is developing ambitious annual and five-year plans, where again the joint emphasis is on growing grains and supplying nutritious food. Several farmers are experimenting with crop mixtures as a means to reduce inputs and improve the agricultural environment.

A summary of their conference in late 2019 is given on the We Knead Nature web site [1]. Long term plans include a hub for growers, customers and businesses, a Seed Bank of local saved-seed grain crops, and greater community engagement through formal education and kitchen skills. Contacts through Facebook and Instagram [1].

Seed Sovereignty UK and Ireland Programme

The Programme’s web site explains its aims and purpose: “The Seed Sovereignty Programme of the UK & Ireland aims to support the development of a biodiverse and ecologically sustainable seed system here on home soil. Working closely with farmers, seed producers and partners across the seed sector, together we want more agro-ecological seed produced by trained growers, to conserve threatened varieties and to breed more varieties for future resilience.”

One of the main aims of the project is to establish regional and national hubs, networks and collaborations. Contact details of regional coordinators are given on the web site’s About page [2]. Activities include raising the main issues and current difficulties around saved seed, encouraging networks and support hubs, training, databasing, field trialling and participatory plant breeding.

There’s an upcoming Seed Week. Sinéad Fortune, Programme Manager, writes “From 18th – 22nd January Gaia will run our fourth Seed Week, which aims to raise awareness of local, open pollinated, agroecological seed being grown and sold in the UK and Ireland. The timing coincides with growers shopping for seeds for the coming season, and we hope to raise general awareness of the importance of agroecological and locally-grown seed with a wider audience.”

There’s ample opportunity to get involved and if you use social media then here is the tag #SeedWeek.

Sources / contacts

[1] Common Grains is on Facebook and Instagram. A note on the Common Grains Conference Scotland in 2019 is published on the We Knead Nature web site. Thanks to Rosie Gray for recent updates.

[2] Seed Sovereignty contacts and information. Sinéad Fortune, Programme Manager, Seed Sovereignty UK and Ireland Programme sinead@gaianet.org. Web sites: http://www.seedsovereignty.info/ and http://www.gaiafoundation.org/. For previous Living Field contact, see Maria Scholten’s article Boosting small-scale seed production .

[3] Landrace is the term usually given to a crop that is maintained from year to year through saved seed. For more on this site: What are landraces?, Landrace 1 Bere and Ancient grains at the Living Field.