By Gill Banks

The Edible Fungi Club (EFC) was formed in March 2022 by Gill Banks “who has a keen interest in mycology, be it recording fungi in the Tayside and Fife area through forays with the Tayside and Fife Fungi Group (TAFFG) or growing edible varieties”.

Gill writes: “I asked some people within agroecology if they would join such a group and was encouraged to see that people were interested. Because of this, senior management at the James Hutton Institute were approached and asked if it was possible to hold meetings for a club in the Living Field polytunnel, which at that time was unused. After consultation with various people at the Institute such as Hutton’s Health and Safety and Plant Health officer, and some form filling, the club had an area in which to meet.”

Edible | Exotic | Gourmet

The aim of the EFC is to provide “edible exotic and gourmet mushrooms” to people who may not have access to them (such as Lion’s mane which is a red listed protected species in the UK) and to encourage people to recycle some waste products such as cardboard and coffee grounds. The club also wishes to explore other uses of fungi such as making clothes, packaging, myco-remediation and eventually medicinal aspects.

The Institute’s Social Club kindly donated £100 to help start up, the farm staff gave bales of straw and an Aberdeenshire farmer donated 75 kg of spring barley that is used to produce grain spawn (see below).

The club charges £2 a session to cover costs of items such as wood pellets, mushroom bags, and liquid cultures, syringes, needles and so on that are required to successfully grow predominantly straw- and wood-loving mushrooms such as: Pink Oyster, Yellow Oyster, Summer Oyster, Blue/grey Oyster, King Oyster, Lions Mane, Black Pearl (a blue/grey Oyster and King Oyster hybrid) amongst others. The club can produce liquid mycelium, grain spawn (see photos below) and provide mushroom kits/substrates at a much-reduced price if members want to grow mushrooms in their home.

Grain spawn

Grain spawn is easy to use and an inexpensive method to bulk up mycelium. The process begins in a petri dish or liquid culture and can take several weeks to months depending upon the mushroom that is being grown.

In the photographs below, from left to right, we can see a petri dish with king oyster mycelium, liquid culture, and grain spawn.

The mycelium is the root-like, vegetative body of a mushroom that can be obtained in several ways, including from tissue culture, liquid culture, or spores. Liquid culture is a nutrient-rich solution that contains the mycelium and is used as a medium for growing and propagating mushroom cultures.

The mycelium when suspended in a nutrient solution, will grow, and is then used to inoculate substrate (in this case barley grain) to provide grain spawn. which will then be transferred to a medium that contains all the necessary nutrition to allow the mycelium to grow further. Eventually, the mycelium will fruit as shown in the photographs below.

Growing interest

The numbers of participants had originally been capped at 10 so that the club would have plenty of resources for its members. There are now 24 members with regular enquiries from people who wish to come along. All are welcome and our members come from within the James Hutton Institute community but also include members of the public who have heard about the club, usually by word of mouth.

Here are some of the results!

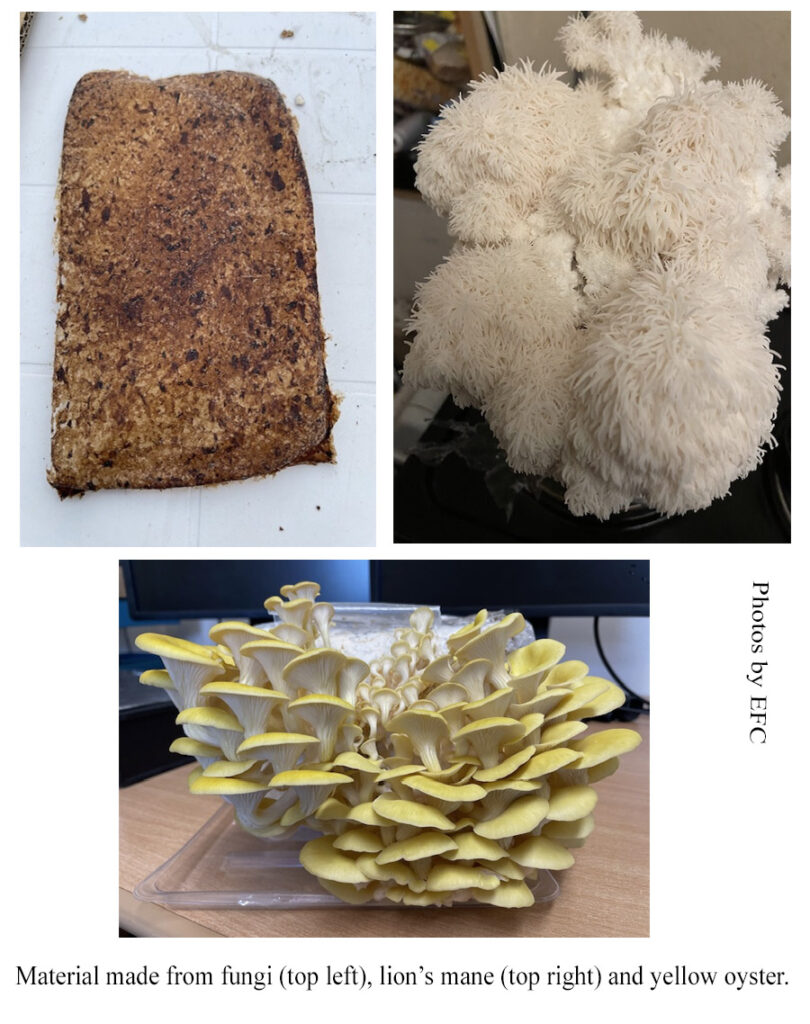

Mushroom paper

The material in the top left picture above is a version of paper made from Dryad’s saddle (Cerioporus squamosus) a basidiomycete bracket fungus also known as pheasant’s back and considered a good edible especially when it is young. This is one of the mushrooms that the EFC hope to grow in the future as it thrives on dead or dying wood. The cell walls of mushrooms are made from a biological polymer called chitin which is similar to cellulose from which plant paper can be made, so we thought that it would be an interesting thing to do.

Dyrad’s saddle proved a good candidate for paper making as it has strong fibres. The Dryad’s saddle was cut into pieces and put in a blender with a small amount of water and then blended until the mushroom became a pulp. We poured the slurry into a wooden frame with mesh underneath and let the water drain out, and then used paper towels to absorb excess moisture. Different mushrooms produce different coloured paper of differing strengths.

Food and medicinal

The second picture (next to the mushroom paper) is Lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus), which has a long history of use in East Asian medicine. We grow it using hard wood fuel pellets and some soy hulls (to provide extra nutrition). In the UK lion’s mane is protected under Schedule 8 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, but it is an easy mushroom to grow as it has aggressive mycelium. Its health benefits are believed to support mental health, the immune system, brain function and stress responses. In addition, they have been reported to help people get to sleep. Depending on conditions, this mushroom can take from 3-5 weeks from grain spawn to fruit (produce mushrooms). It is a mushroom that does not taste like the average supermarket mushroom. It has a mild, sweet, taste with a firm and meaty texture.

Cooking mushrooms

The best way we find to cook mushrooms is…. Simply. We usually start off with a high heat to remove excess moisture, then lower the temperature, add some olive oil and/or butter with salt and pepper and fry. With any new mushroom it is best just to try a little amount first as some people may have some undesirable reactions which are usually due to the chitin content of the mushrooms.

The taste can change with length of cooking. For example, the third picture in the group above is of yellow oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus citrinopileatus), otherwise known as the golden oyster mushroom. This is a fast-growing mushroom with lots of fruits, and as it is a warm-weather strain, it isn’t found in the UK. This strain of oyster mushroom can be grown on a wide range of materials from supplemented sawdust, straw, coffee grounds and/or cardboard.

These mushrooms lose the yellow colour when they are cooked. If they are undercooked, they taste bitter, but if they are cooked for the correct amount of time, they have a balanced “nutty” flavour. If they are cooked until they are crispy then they can taste a bit like bacon. This species can produce mushrooms from grain spawn in as little as a week if the conditions are correct.

Author | contact

Gill has been approached to do a podcast, a talk at Dundee University and asked if she was interested in writing a book. Who would have thought so much could happen in under a year? It just shows that in this case the world is indeed your oyster (mushroom!).

Gill Banks (PhD) is a researcher based in the Agroecology group at the James Hutton Institute, Dundee. The polytunnel lies in the west side of the Living Field garden sited on the Hutton’s Mylnefield Farm.

Contact: Gill.Banks@hutton.ac.uk

Ed: thanks to Gill for this note on the Edible Fungi Club – it’s good to see the Living Field polytunnel in use again.

[Published 14 January 2024 – minor editing possible over the next few days]