The wheats, barleys and oats – known together as corn or cereal crops – are the mainstay of the croplands.

Origins

The cereals were all domesticated from ‘grasses’ around 10,000 years ago. The ones typical of the croplands – wheat and barley – arose in Mesopotamia or the Fertile Crescent, east of the Mediterranean region. The origins of rice were in east Asia, of maize in Central America and of sorghums and millets in Africa.

Wheat and barley arrived here over 5000 years ago, brought by the first farmers in their migrations from mainland Europe, either west along the Mediterranean and then north through what are now Spain and France, or north-westwards across central Europe. And in one form or another, they have sustained people and their farm animals ever since.

Cereals in the croplands today

Some of the first to be grown here in the neolithic and bronze ages, such as emmer wheat, are either absent now or very rare. Today, barley, wheat and oat, in that order, are the main arable crops in this region – arable meaning they are grown on ploughed land – and usually sown each year. Right through the 1800s, and for much of the 1900s, they were still grown as the main source of food for people and farm animals.

Now, while cereals are still grown for animal feed, the main economic output is as raw materials for whiskey, gin, lager and beer. Except for oat in the form of oatmeal, porridge and biscuits, most cereals eaten by people here are nurtured in other lands. Bread, rice, pasta, polenta and maize are all imported.

Yet the croplands produce good cereals – high yielding due to the long drawn-out phasing of the crop over the cool summer, the high total solar income between April and September and the general absence of drought and nutrient deficiency.

The 20th century conversion from local consumption for food to what is mainly a food-import-alcohol-export economy can be sustained only if external sources of grain, fertiliser and animal feed supplements can be guaranteed. The countries of maritime Atlantic Europe are far from self-sufficient in staple cereal food.

The Living Field garden grows a set of six to eight cereals each year, including the older emmer, spelt, rye, bere barley and black oat, contrasting with modern varieties of wheat, barley and oat.

Wheat

Several species and types of wheat are grown in the garden: our common wheat Triticum aestivum, known widely as bread wheat, and two other species – emmer and spelt.

Emmer Triticum dicoccum was one of the first cereals to be domesticated in the fertile crescent more than 10,000 years ago. There is archaeological evidence of its presence here, but it is no longer grown. It germinates quickly, then grows tall, over six feet in some years, but when its heads start to form and fill, it falls over in the wind and rain. Its seeding head is agreeable, clean and neat.

‘Bread’ wheat Triticum aestivum was also domesticated in the fertile crescent. In the croplands, it is mostly planted in the autumn as ‘winter’ varieties to be harvested in late summer or early autumn the next year. Fewer fields are grown of spring wheat, the same species, but planted in late March or April and harvested September (as in the garden). The compact head of modern types, packed with grains, contrasts with the longer, more awny, barley; but it also contrasts with the longer, looser heads of old landraces of the same species and the other wheat species, emmer and spelt.

Most years, a modern short wheat variety is grown alongside a tall landrace of the same species, known as ‘Red Standard’. The modern wheats pack their grain into a stubby head but yield many times more than the landrace. Although known internationally as bread wheat, the types grown in Scotland and harvested mostly for alcohol production or animal feed.

Spelt Triticum spelta is thought to have arrived later than the emmer and bread wheats, and like the emmer is no longer grown here. Its flour or finished products are imported for bread or crackers. The plant is much like emmer in germination, growth rate and height.

Barley

The convention adopted on the Living Field site is to name all barleys cultivated in the British Isles Hordeum vulgare. Most barley is now sown as named commercial varieties, but in the 1800s, many informal lines existed including the landraces, collectively known as bere.

Barley Hordeum vulgare is now the commonest cereal in the croplands, replacing oat in the 1950s and 1960s. Its seeding heads bend horizontally or even downwards when mature and carry long awns arising from each grain. The grains are in sixes round the stem, but in many modern types, four of the six do not develop, so the head shows two rows. Some commercial varieties retain the six-row structure (photographs below).

Bere is the name given to the traditional landraces of barley which persist in a few localities in the far north and west, but have mostly been replaced by modern varieties. The head or ear has characteristic long awns and arcs as it matures, giving the impression of fish jumping out of water (photograph middle right below). Bread and bannocks can be made from the flour.

Oats

One hundred years ago, this was the most widely grown cereal used to feed people, horses and stock animals. Two species have been grown here but the black oat is now very rare as a crop.

Oat Avena sativa is another of the ancient cereals, but the one having lax heads or panicles, the grain held on longish stalks, unlike close to the stem in wheats and barleys. It probably arrived here later than the wheats, yet it became the dominate cereal for many centuries until barley came to prominence in the mid-1900s. Highly nutritious and hardy, an ideal cereal for the croplands, locally grown and locally processed, but covering less than 10% of the cereal area now.

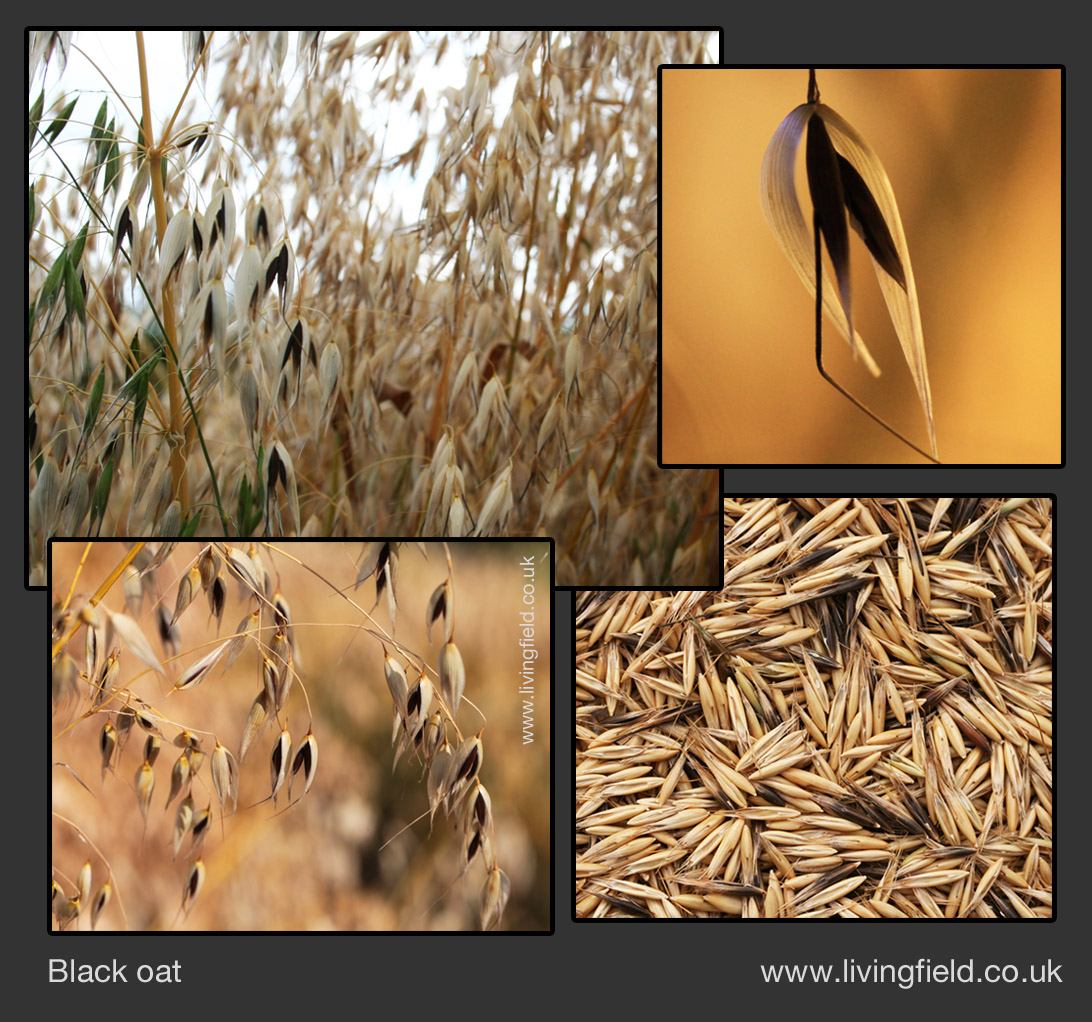

Black oat Aven strigosa also known as bristle oat, was once grown widely for animal food, and even human food in times of duress, from which it became known as ‘famine food’. It has this highly characteristic, black grain held on a very lax panicle, but though it grows well, the ratio of grain to total mass is too small for it to be economical as a grain crop.

Photographs above show (top left) part of the stand having mature (black) and young (green) grains on different plants growing close together, As for bere, the plant is still part wild and has not been selected to develop at the same rate on all plants or branches. The grains (lower right) are longer and thinner than those of oat. Each spikelet (upper right) usually supports two grains, partly protected in a papery sheath.

Rye

The rye Secale cereale grown in the Garden is a landrace from the Western Isles. It grows taller then bere but shorter then emmer and spelt. The ears are upright when they emerge from the leaf sheath but then bend, as shown top left in the photographs. The whole plant has a tinge of blue-grey about it when young, but a ragged, straw coloured look when mature (lower photographs).

Rye has never been a major crop here. Yet it features in poetry and traditional song at least as much as barley. Its importance on the grain lands could be increasing, new varieties now grown for feed and whisky.

Maize

The most recent of our cereal crops, maize Zea mays was domesticated in Central America at about the same time as the wheats and barleys were in Mesopotamia. But while wheats and barleys could travel overland from their centre of origin, maize had to wait until the late 1400s before ships could make the journey from Europe to America and back.

Maize is not grown widely in the north, where its commonest usage is as food for farm animals, but we grow several varieties each year in the Garden, usually those that give ‘sweet corn’ within a few months of growth in summer.

Maize is unusual in having male and female organs on different parts of the same plant. The male ‘branches’ tend to appear at the top of the plant (upper images above), the female lower down (lower images), sometimes in clusters. The grain sites in the female organs are contained within a leafy sheath (lower right above); each site puts out a tube that extends outside the protective sheath of leaves.

The mass of tubes together is known as a ‘silk’ (lower left). When pollen from male flowers falls on one of the threads, it puts out a pollen tube that grows down the thread, into the sheath and then to the grain site from which the thread emerged.

Maize is a major global crop, its large grains, not individually encased as in barley for example, are easy to remove and cook. After its arrival in Europe, it took only a couple of hundred years for maize to spread through Africa, Europe and Asia.

Management

The cereals grown in the Garden are all spring-germinating, grow quickly and mature in September. They germinate within days of being moistened, and spend their first few weeks in a glasshouse to ensure we have enough plants and to avoid early problems with grazing animals.

When planted out they are vigorous and seem so far to be little afflicted with disease. They are grown in small plots and have to be staked, because all but the spring wheat tend to fall over (lodge) in wet and windy weather.

The cereals are cut and threshed when mature and the seed kept for the next year. The original stocks of emmer, spelt and bere barley were given to us by Orkney College, and the rye and Red Standard wheat by SASA in Edinburgh. For a display of barley varieties in 2015, seed was provided by the James Hutton Institute barley collection. Maize is usually given by Jim Wilde from the glasshouse team.

Links to Living Field articles on cereals

Barley and bere

- Photographs of the 2015 barley collection in the garden

- A series of notes and articles on barley and in particular its landrace known as bere – links to the thread are at Bere line – rhymes with hairline.

- Articles in the Bere line include Bere in Lawson’s Synopsis (1852), and What are landraces?,

- Bere and cricket – bread made from bere and insect flour.

- Bere recipes e.g. Oatcakes with bere meal, Bere shortbread.

Maize

- Cornbread, peas and black molasses – the deficiency pellagra caused by dependence of the impoverished on maize meal; also the remedy and benefit of green vegetables at Peanuts to pellagra and 2 Veg 2 pellagra

- Maize paper – making papers from stalks, leaves and husk; and more uses of the plant at Maize husk for art paper and cheroot wrapping.

Images/text this page: Squire / Living Field