Maize, along with rice and wheat, and to a lesser degree barley, provides most of the cereal or corn harvest for the world’s civilisations. Maize was domesticated in the Americas and did not arrive here until recent centuries, when ships and navigation were advanced enough to sail across an ocean.

Maize is a warm-climate crop [1] but consists of many varieties, some of which can be grown here in summer, where it’s product is known as corn-on-the-cob or sweet corn. It is also grown in stock farming as an animal feed, but mainly in the south of the UK.

Yet maize has many other uses. Here we look at two of them, both starting with the husk surrounding and protecting the cob – Jean Duncan’s exploration of paper-making using husks from maize grown in the Living Field garden, and the traditional use of maize husk as wrapping for Burmese cheroots.

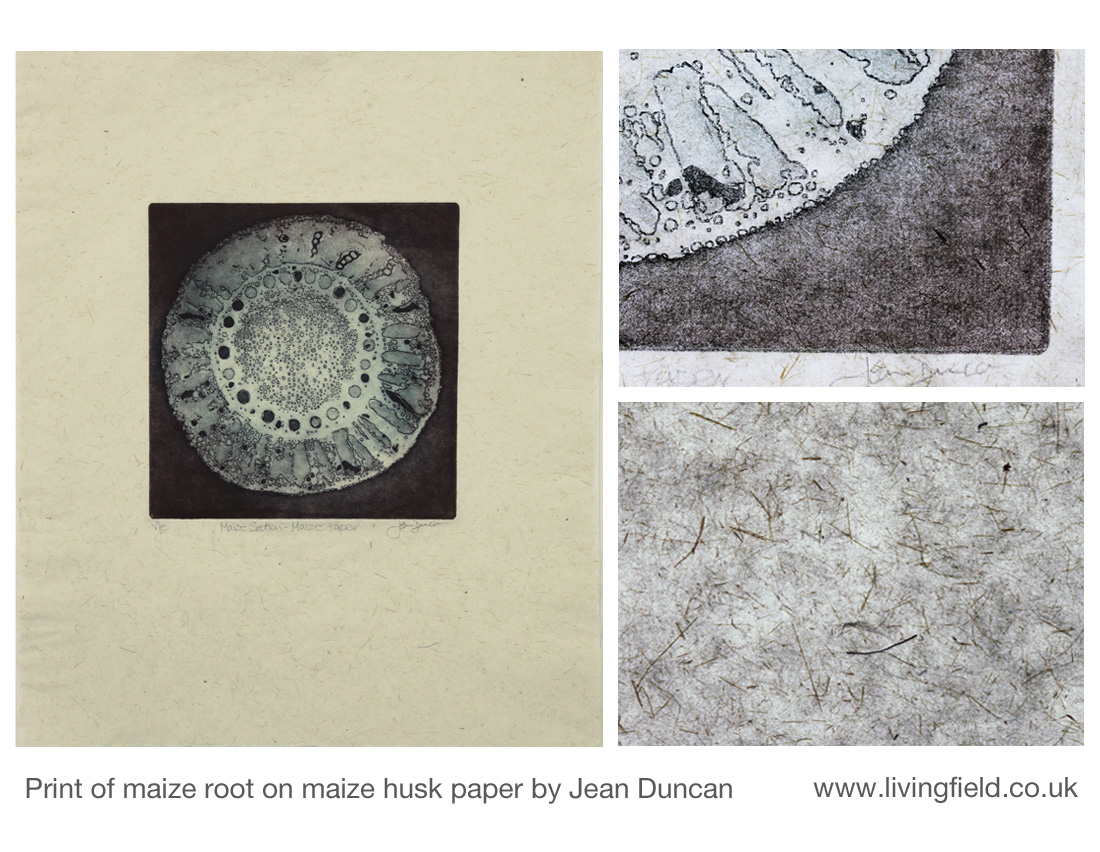

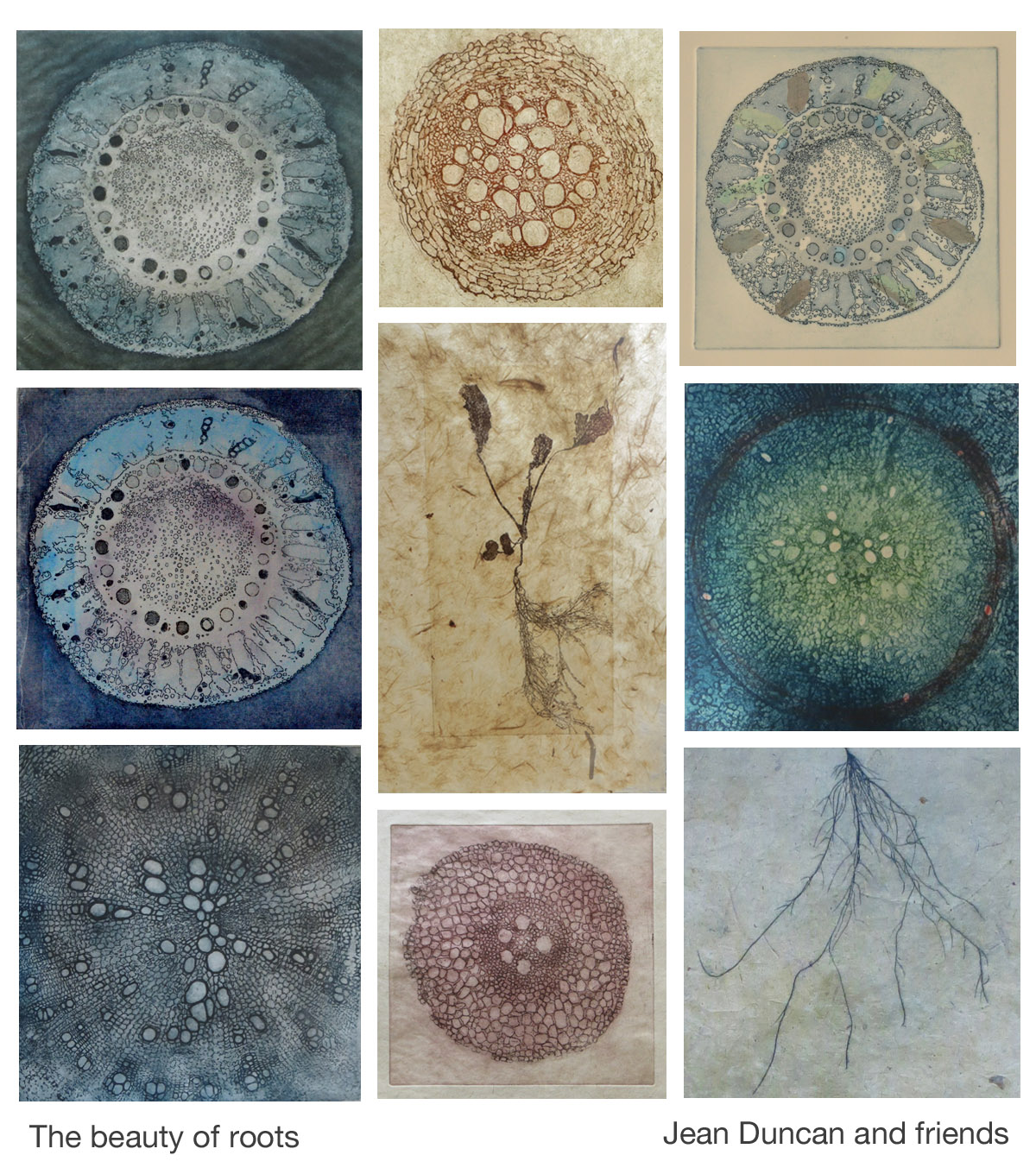

Print of maize root on maize husk paper

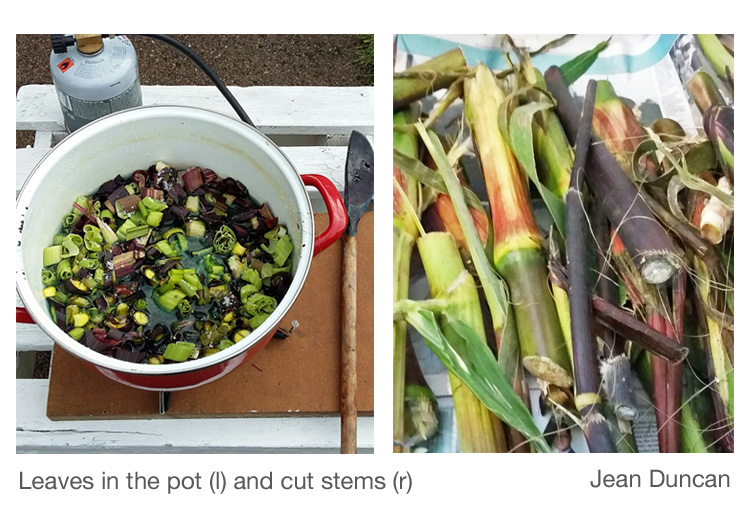

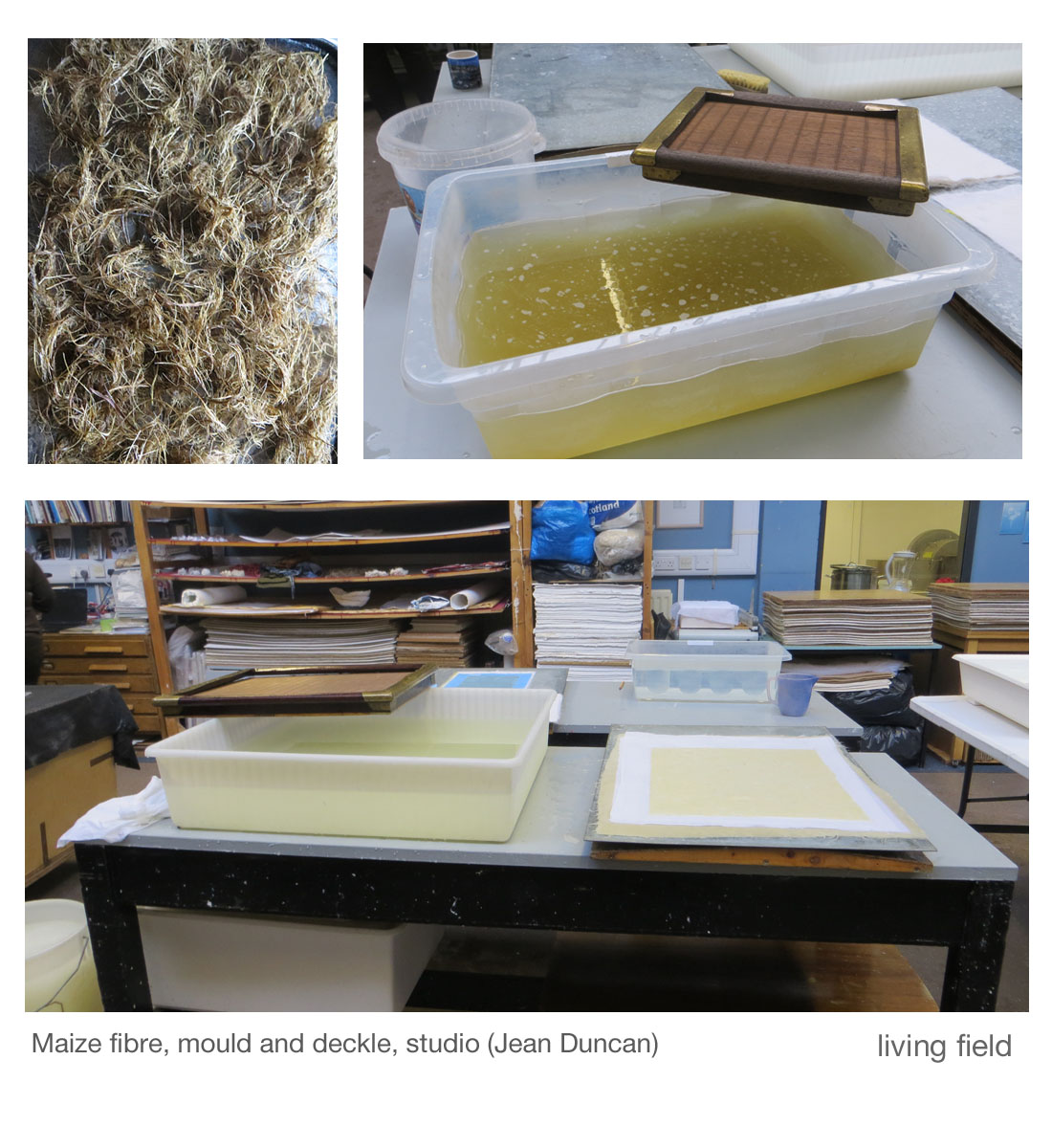

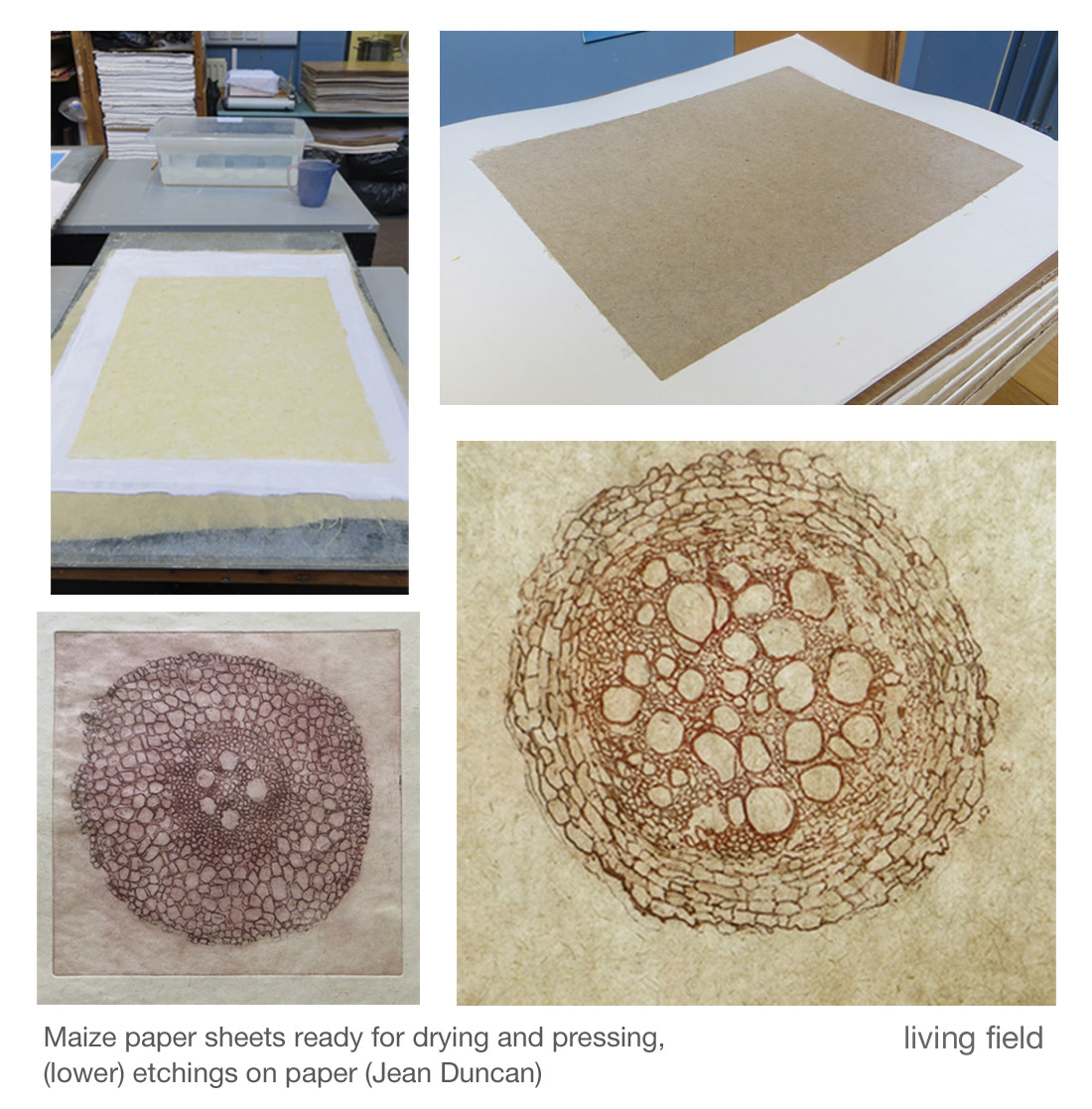

For making plant paper, Jean tried various parts of the maize plants including the leaves, the thick stems and also the papery coverings of the flowering and fruiting head, known as the husk, which she said made the best paper [2].

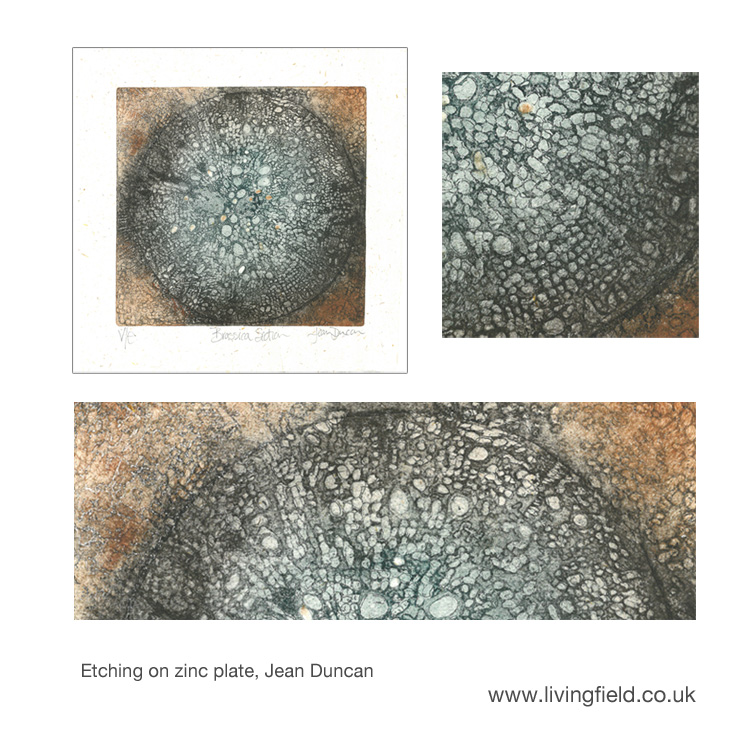

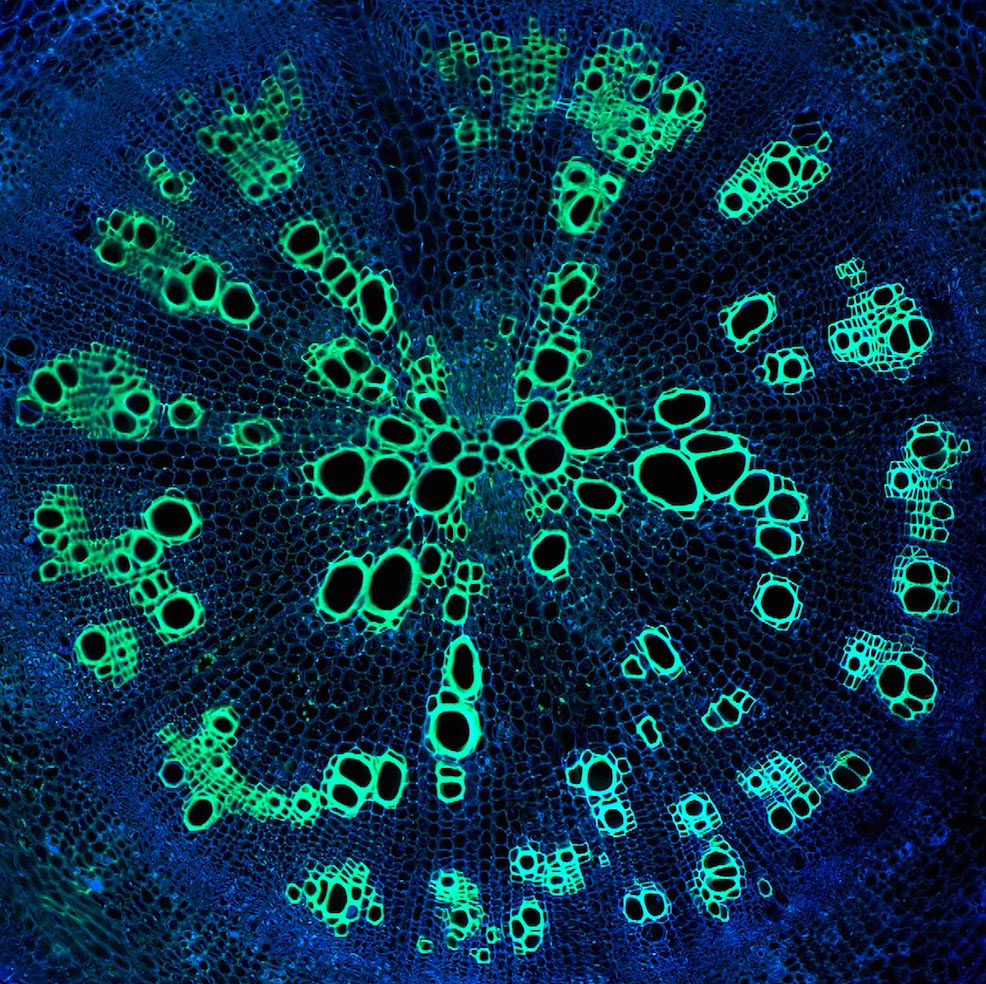

The images above are of a print on maize husk paper of an etching of a maize root cut in cross section and magnified so that the internal structure can be seen.

In the print on the left hand side of the images, the original root cross section is about 1 mm wide, the image itself is 22 by 22 cm and the paper 40 by 49 cm. To the right are close-ups of part of the print and of the paper, showing the visible fibres from the original husks, now converted into paper.

The paper in this case became a visible part of the finished art. Sources below give links to Jean’s description of making the paper and an exhibition in which images of roots were printed on various plant-based papers [2].

Burmese cheroot wrapping

Once it was brought across from the Americas, maize travelled quickly in the 1600 and 1700s and became a favoured cereal through Africa and among the warmer parts of Europe. It established also in Asia, but usually as a secondary crop behind rice.

Its parts were used not only for food for humans and animals. There is a history of usage as a medicinal, as a substate for alcohol (e.g. chibuku in Africa) and curiously, as a wrapping for cheroots.

The long cigar shaped structures smoked in Burma (now Myanmar) and known as cheroots are usually filled with a range of herby and woody plant material, not always including tobacco. The wrapping can come from a range of plants, but the cigars below were wrapped in maize cob husks [3].

Several husk-leaves were used to wrap each cheroot. The contents were, as said above, derived from a range of plant material, most pieces being 2-4 mm long. Each cheroot had a filter, consisting of tight rolls of leaf or husk. They were on sale locally along the Irrawaddy River in Burma, now Myanmar [4].

Several husk-leaves were used to wrap each cheroot. The contents were, as said above, derived from a range of plant material, most pieces being 2-4 mm long. Each cheroot had a filter, consisting of tight rolls of leaf or husk. They were on sale locally along the Irrawaddy River in Burma, now Myanmar [4].

In his compendium of useful plants, Burkhill [3] notes that an industry arose in north Burma at some time in the last few hundred years, based on the use of a type of maize, characterised by a waxy endosperm (the store in the seed), which also had a ‘peculiar suitability of the sheath for cheroots.’ He also refers to the possibility that certain impoverished areas were afflicted by the vitamin deficiency pellagra through reliance on maize, as in parts of the USA [5].

Male and female flower heads

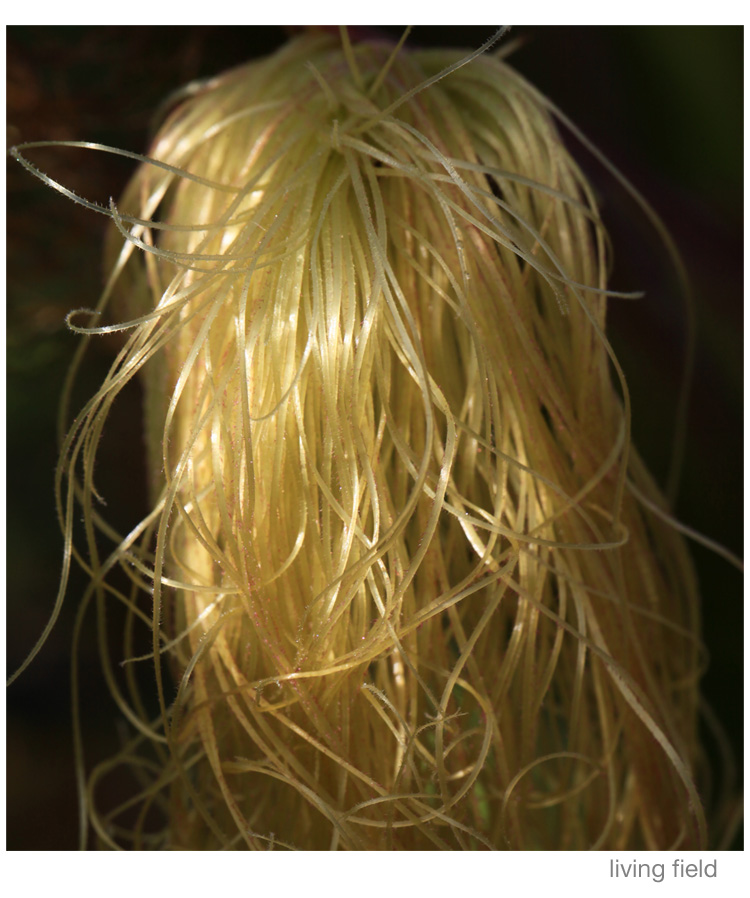

Maize is unusual among the cereal or corn plants in having separate male and female flower heads, each on compact ‘branches’ held on different parts of the same plant. The male flowers are usually held at the top of the plant and the female lower down. Female branches are shown in the images below, taken in the Living Field garden.

The female flowering head remains mostly hidden within a sheath of leafy material (above left) that later forms the husk. The grain sites are arranged around the central ‘stem’ hidden by the sheath. The stem and grains together will later form what we know as the corn cob.

The female flowering head remains mostly hidden within a sheath of leafy material (above left) that later forms the husk. The grain sites are arranged around the central ‘stem’ hidden by the sheath. The stem and grains together will later form what we know as the corn cob.

Each grain site puts out a long thread, many of which together emerge from the sheath in an irregular bunch, often named a silk, the female part of the reproductive process in this species (seen reddish, above left and top right).

The function of each female thread (comprising a stigma and style) is to receive pollen from male flowers and to provide a channel for the pollen tube, that emerges from a pollen grain, to grow into the sheath to a grain site. When pollinated, the grain sites fill to give the familiar, yellow kernel which remains protected by the sheath.

Sometimes the season in the Garden is too short for late flowering maize heads and they do not grow into a finished, filled cob. One of these late heads was prized apart to show an undeveloped cob (lower right in the images above) and the surrounding sheath that had turned to parchment in feel and colour. The female threads, now fibrous and dead, can just about be seen issuing from each grain site.

The paper shown in the images at the top of the page was made from husks like these.

Finally, here is an image of maize intercropped with groundnut growing by the Irrawaddy river [4]. The male branches can be seen at the top of some of the plants. Female flowering heads are circled.

Sources, references, links

[1] The botanical name for maize is Zea mays. The genus Zea is of the grass family and has only this species. It was domesticated and developed many thousands of years ago in Central and South America. It was first brought across the Atlantic Ocean in the late 1400s, then spread rapidly east.

[2] The article Maize paper by Jean Duncan describes how to make paper from plants in the garden. The exhibition The Beauty of Roots shows prints and etchings made on maize and other plant papers displayed at the University of Dundee in 2017.

[3] Details of the spread and growing of maize in Asia are given in the major compendium of useful south-east Asian plants by Burkill, published in 1966, but clearly the result of many decades of investigation and cataloguing. He lists the use of maize husks for cheroot wrappings and of maize leaf and stem for paper.

Burkill IH. 1966. Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsular. Two volumes, 2444 pages. Published on behalf of the Governments of Malaysia and Singapore by the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The entry on maize is in Vol II at pages 2327-2334.

The writer refers to the following article for confirmation of the use of ‘waxy’ maize varieties as cheroot wrapping in Burma: Collins GN.1920. Waxy maize from upper Burma. Science 52, 48-51. doi 10.1126/science.52.1333.48.

[4] The cheroots shown in the images were bought at a village store in 2014 on the banks of the Irrawaddy. Further description of the region is given at Mixed cropping in Burma on the curvedflatlands web site in an article by G R Squire. Disclaimer – no cheroots were smoked in the research for this article!

[5] The Living Field we site has the following articles on maize and pellagra: Cornbread, peas and black molasses and Peanuts to pellagra.

Contact/author: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk