Natural dyes have been around for a long time. Whether for vanity, art, craft, industry – people have found plants that produce colour if treated in certain ways and colour that sticks for a time in fibres or wood.

People living at the sharp end – hunting to sustain themselves or growing the first crops – had the curiosity to see which plants and which plant parts held natural dyes. And the plants and parts are not obvious. Presented with some leaves and roots of indigo or woad, who today would think they concealed such rich natural blues, and how can the weak greens and browns of madder, sorghum and brazilwood conceal their depths of red.

Plant dyes had been used in the croplands well before the first crops came here. Lichens, the bark of shrubs and trees, oak galls, whins (Ulex), berries, nettles, all were used to add some colour. Much later, a few dye plants were grown as crops, including woad for a time; but the strong natural dye colours came from hot countries. The tropical legume, indigo, supplanted woad as the blue dye of choice in the late 1800s, and local plants could not compete with the imported red-sorghum, brazil wood and the insect-based cochineal.

In turn, these tropical dyes were ousted in the 1900s by industrially made pigments; and most commercial dye cropping in Britain ceased around 100 years ago, as did much of the import trade in natural dyes from around the world. Yet still in a few places, in certain forms of craft work and where the subtlety of natural colour is appreciated, dye plants find their place.

Despite their lack of commercial value today, there is something about dye plants that has a fascination – we would not have known about the cabbagy woad, the stunning composite coreopsis, the broom-like greenweed, and the red-relative of the noxious weed cleavers – not all easy to germinate and grow to say the least – if we had not been tempted to explore the natural dye plants that had been cropped or imported here over the past few thousand years.

The garden keeps about fifteen species that have been grown or collected at some time in the croplands to make dyestuffs. The hedges hold a few of the perennial woody plants, and the meadow a few of the herbs, such as lady’s bedstraw. A small, cultivated bed holds woad, madder, tansy, chamomile, coreopsis, alkanet, weld and greenweed.

Here are some of the species.

Weld Reseda luteola is now uncommon in farmland but appears on wasteland, particularly in towns, where it tends to last a year or so before being sprayed. Weld is commonly biennial, germinating and forming a base of leaves in one year then extending and flowering the next. The leaf and stem are harvested and dry to a light straw. They give a yellow dye as shown colouring wool in the panel above.

Madder Rubia tinctorum is a perennial that overwinters and comes up each May but never grows into much. It is a relative of the bedstraws and close to one of the worst arable weeds in the UK (cleavers). It was once gown in Britain as a commercial dye plant, red pigment in the root. Madder was much sought after because of the strength of its red, unusual among the plant dyes (centre in the panel higher up the page contrasting with weld and woad).

Dyer’s greenweed or dyer’s broom Genista tinctoria is a shrubby perennial, a nitrogen fixing legume, producing yellow flowers similar to those of broom and gorse. The seeds were difficult to germinate and the seedlings grew slowly, but after a few years the plants are well established at both ends of the small dyes bed.

Tansy Tanacetum vulgare is one of the most strongly smelling, aromatic plants in the garden. Its button-like, composite flower heads are raised each year on plants in both the dyes and medicinals beds. It spreads vegetatively, farther than you expect, and needs to be contained or it overruns.

Lady’s bedstraw Galium verum is a multi-purpose plant growing in the meadow and used to make a yellowish dye.

Alkanet Anchusa officinalis is a perennial member of of the borage family and in the same genus as the weed bugloss Anchusa arvensis, but despite the common name, the one grown here is not the dyer’s alkanet whose roots have been widely used to produce a red dye.

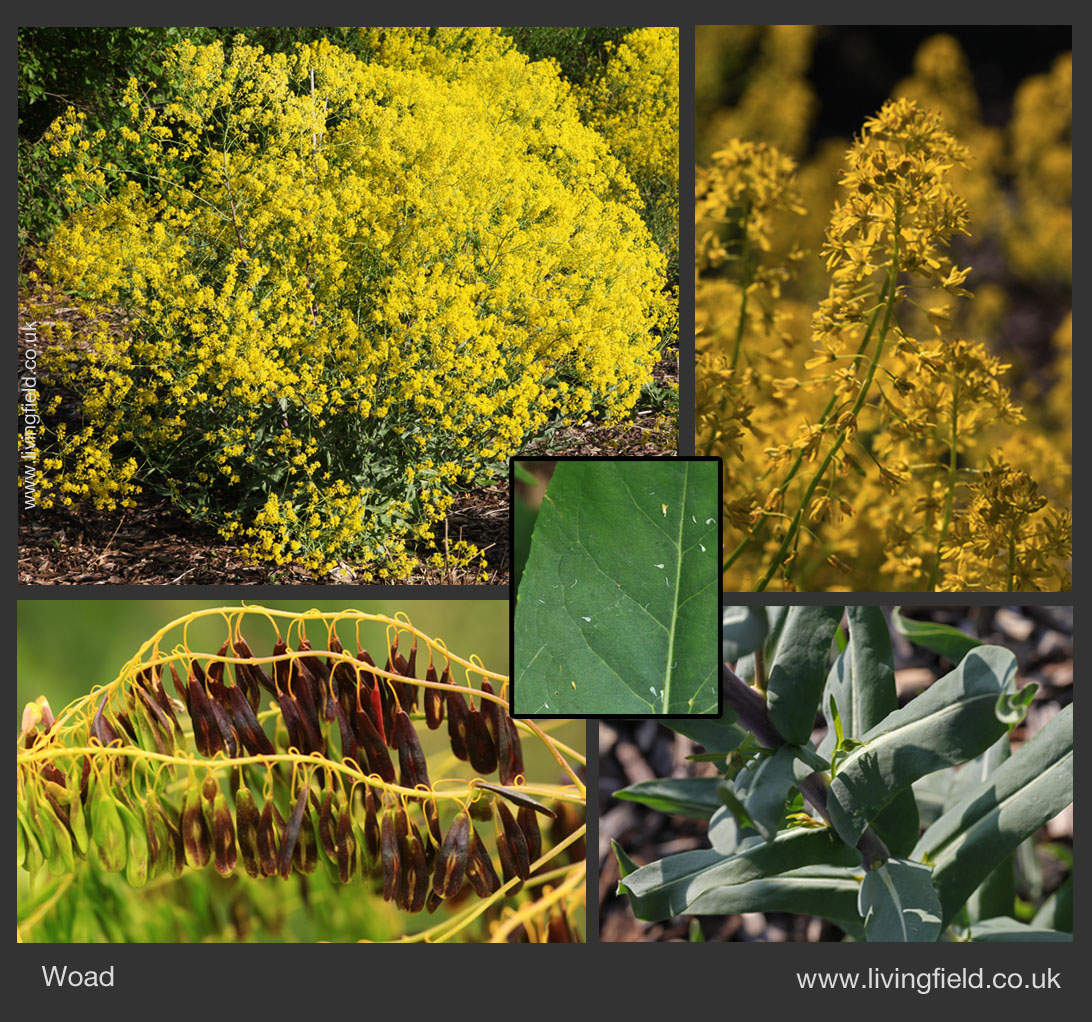

Woad Isatis tinctoria is one of the cabbage family, a biennial leafing one year and flowering the next. The blue dye is extracted from the leaves. One of the first in the garden to flower each year, the yellow fuzz in May giving way to a black mass of seed pods in late summer. The woad in the garden now self-seeds, but we usually germinate a few under glass each spring, just in case. One of the few dye plants to have been grown commercially in the north.

Dock Rumex obtusifolius forms a thick upper tap root which can be peeled, sliced and boiled to give a yellowish dye.

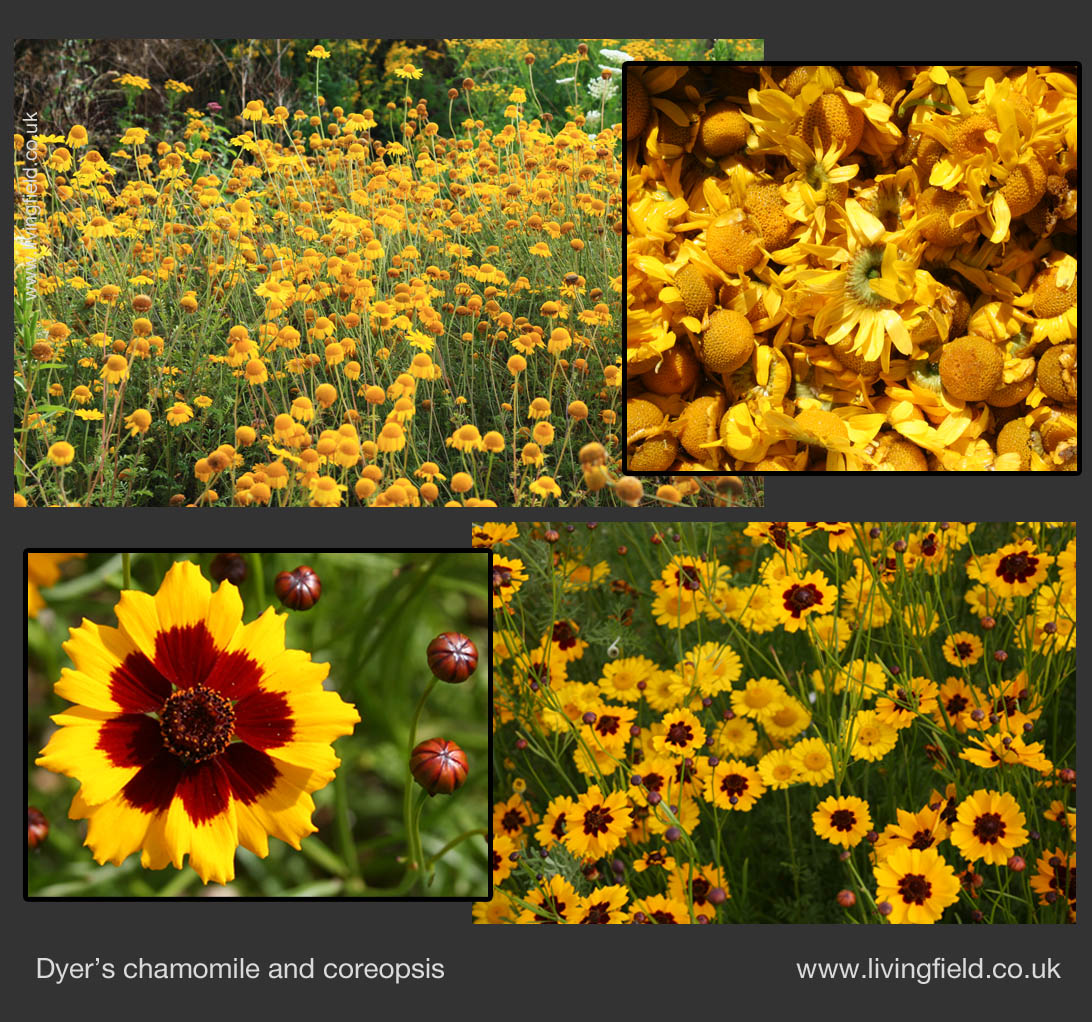

Dyer’s chamomile Anthemis tinctoria is a short-lived perennial that flowers profusely in summer, similar to coreopsis in being a composite, but distinguished by the finely dissected foliage with a silvery tinge and the all-yellow heads (shown in a photograph below). Like woad, it now self-seeds in the garden.

Dyer’s coreopsis Coreopsis tinctoria is, like the chamomile, one of the composite family, and one of the most striking of that family with its flowers of yellow and deep red. The plant is an annual, needing to be resown each year under glass and planted out.

Rhubarb from the genus Rheum,the well known garden vegetable, eaten sweetened in puddings or simply stewed, is a relative of the docks, as is evident if let to flower. A deep yellow-brown dye comes from boiling the ‘roots’ cut into small chunks

Several trees have been used traditionally for dyes, including …

Oak Quercus robur and Q. petraea produces dark, spherical galls from which a black dye or ink is extracted. There are no oak in the garden, but galls can be seen on young trees planted along nearby farm roads. Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing ‘Sprigs of oak and dyer’s greenweed’ was exhibited in Dundee in 2012.

Hazel Corylus avellana catkins appear in March and last for a few weeks sometime dusting nearby objects with masses of pollen. The catkins produce a subtle, light creamy dye.

And Birch Betula pendula and Betula pubescens yield a dye from their bark.

Other plants used as a source of dyes include whin or gorse Ulex europaeus, which is a legume, high in protein, and once used as an animal feed when pulverised to reduce the spiny branches to pulp; and stinging nettle Urtica dioica which yields a green dye from its leaves.

From the archives

March 2012: “And the root parries the adversary ….. Take the common rhubarb, a cooking vegetable, a medicinal with an ancient lineage and a source of rich deep yellow dye. On slicing a plant in half, with the intention of moving a piece of it to the dye plants section in the Living Field garden, the remains of subsurface battles were unmissable. Assailed by things that dissolve, suck, chew, bite and bore, the ‘root’ fights back with outgrowths of new tissue, sticky mucilage and dark protective coverings. The heading is from Christopher Smart’s poem Jubilate Agno (Rejoice in the Lamb) where the adversary is the devil, but the roots and stem tubers of plants – once so essential as food during the winter for people and their animals – perpetually fight adversaries by the million.”

Management, sources and further reading

The dye plants are treated the same as other wild plants, in that they are mostly left alone to survive and grow. Woad self-seeds and needs to be clumped every year or so by moving plants. Dyer’s chamomile survives over the winter as mature plants but coreopsis will not survive here as plants or seed and needs to be re-sown.

The only plant that needs extra care is madder, which does not grow well here; it needs careful weeding and some support, but the red colour visible when the roots and stem bases are disturbed is a surprise.

Background reading

The 5000 Years pages on this web site include a section on plant dyes and suggest books and web links on dyes and dye plants, including:

- the Wild Colours web site gives much general background and practical information, and offers a wide range of dyestuffs, dyes and seed of dye plants for sale: http://www.wildcolours.co.uk

- The Scots Herbal by Tess Darwin published by Berlinn.

The Living Field arranged for wildcolours to provide some hanks of wool dyes with woad, weld, madder, indigo and a range of tropical dyestuffs. Plant material from weld and madder, with woad powder, are contrasted with three hanks of wool in the panel near the top of the page.

Author/contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com