Hedges and trees form vertical and linear features in cropland that act as windbreaks for crops and offer cover and refuge for other plants and for animals. Hedges can grow into trees and trees can be cut into hedges. Many of the cropland’s tree-lines grew out of hedges, while trees cut 1-2 m in height can live to form durable hedges.

Like stone walls, hedges were commonly put in to reinforce legal boundaries and to confine stock. Blackthorn, hawthorn, hazel, elder, alder, pear, apple, rose, cherry, elm, holly, beech, ash are all constituents of hedges. The number of species in a hedge sometimes increases over time as new plants find their way in; but few conifers such as pine, spruce and yew, survive in hedges. Except for holly, the species lose their leaves in autumn and are leafless through the winter.

Tree lines are a defining feature of the croplands. Look at any landscape from a distance and they can be seen or their absence felt. Small woodlands and copses are also planted for shelter and firewood. While tree lines are mostly deciduous – ash, oak, beech, and elm once – copses and farm woodlands can be conifers or mixtures of conifers and deciduous trees.

While some hedges have been taken out to create larger fields, much of the cropland is still well populated with trees and shrubs, some quite magnificent, giving it that characteristic temperate, ‘north atlantic’ look of lush foliage and timeless stability.

Yet both trees and hedges need to be managed – trees fall in the gales, or are felled for wood, and need to be replanted; and the current practice of shaving the top off hedges year after year creates a surface web of branches, hiding internal holes that lead to death and gaps. Hedges also get their unwanted share of fertiliser and pesticide from operations in the field, so have to recover from spray-burn and to compete with aggressive weeds like cleavers, nettle and thistles. The future of the cropland hedge is not assured.

Hedges were planted round the garden and a few trees were put in just north of the pond and ditch. Their influence was immediate – birds sing from the trees and feed off the hedges.

Here are some of the species.

Alder and hazel

Small trees but well suited to hedgerows, their catkins appearing on uncut branches.

Alder Alnus glutinous, of the birch family, prefers wettish soil and is common in the croplands along river banks. In the garden, two have been left near the pond to grow into trees while others appear in the hedges. It has catkins, similar to hazel, and female ‘cones’ that persist, black through the winter. Alder’s wood resists decay and was used as structural support in wet earth or under water (as in crannogs) and also for charcoal and to give a black-brown dye.

Hazel Corylus avellana can also form a small tree, but probably takes better to hedge-life than alder and generally prefers drier ground. While similar in size and appearance to alder, it’s of a different plant family. The long catkins appear in spring with the very small female flowers, which if you look closely, emerge red at the tip of small buds. Hazel nuts have been (and still are) widely used as storable food, its wood for tool handles and long thin re-growth branches for basket-work and fences.

Blackthorn and hawthorn

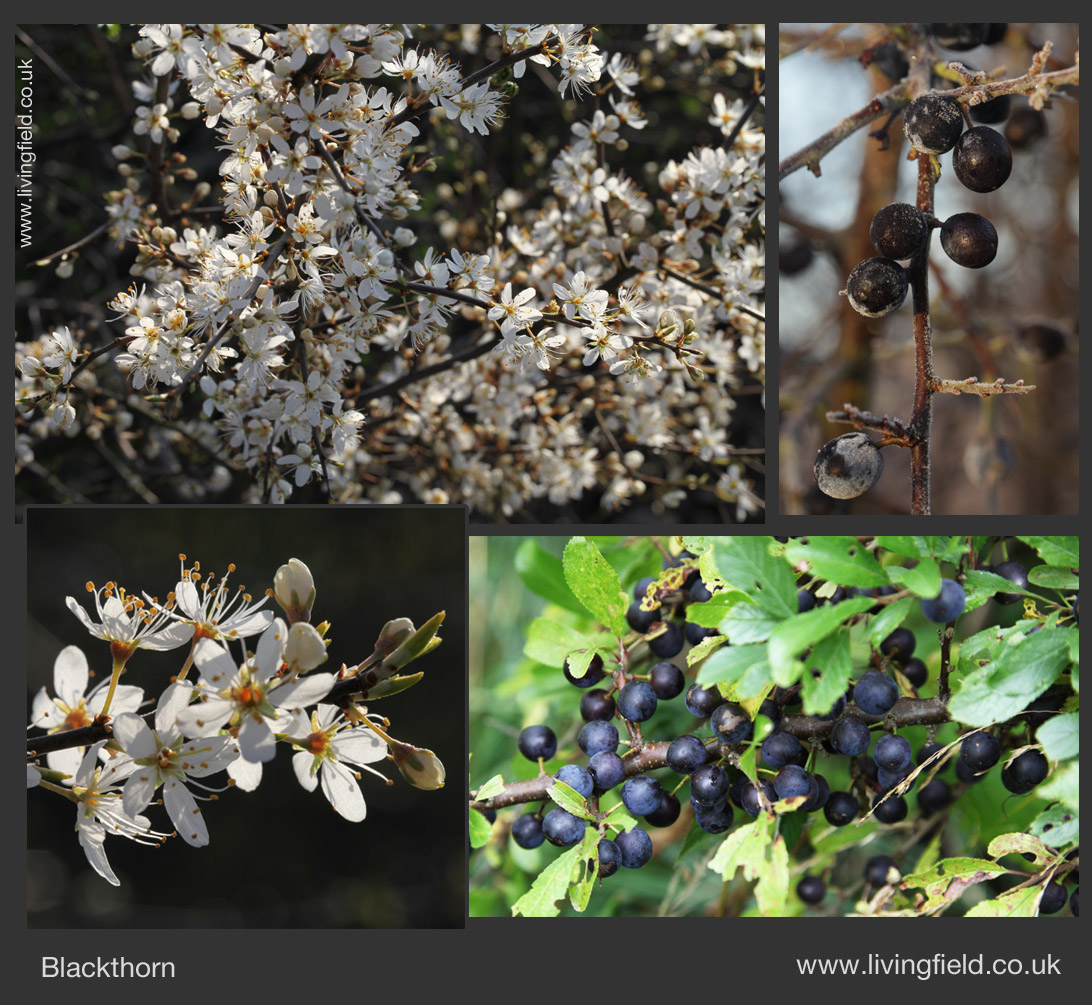

Two dense, spiny, woody species widely used as hedging plants in agricultural land. Both of the Rose family but differ in flowering, leafing and fruiting periods. Both also have a hard wood, resistant to rot and valued for tool handles.

Blackthorn or Sloe Prunus spinosa is the first to flower, provided branches are left to grow long, and is well represented in the Garden’s hedges. It is well-named spinosa. It begins to flower mid- to late-March, usually before it puts out leaf and well before hawthorn. Less visible are the dark blue fruits, sometimes called sloes, turning deep black and lasting most of the winter. While the leaves, flowers and fruits have some uses as medicinals and dyes (see Darwin), blackthorn is better known for the use of its sloes to flavour drinks such as gin and herbal wine.

Hawthorn Crataegus monogyna was planted only in the Garden’s hedges but forms a neat small tree when sheltered and unshaded in the wild. It flowers later than its relatives, the blackthorn, gean and bird cherry, usually around the May cross-quarter day. Its red berries are highly visible in autumn along with rose hips. Hawthorn has probably, of all the small trees, the greatest association with pagan rites and superstitions, some of which continue to the present.

Wild Rose

Species of the genus Rosa extend their spiny outgrowths from all parts of the hedges, growing as small bushes or climbing 3 to 4 m then cascading down. Their small flowers range from pink to white and all shades between. Their bright red or brown hips extend the colouration of the garden and its autumn menu-options for inverts and birds. Several species grow in the hedges, some difficult to identify.

Rose flowers have been long recognised for medicinal and nutritional properties. Ranson writes of ‘Honey of red roses’ (boiled petals added to honey) to ease sore throats and gums and ‘Rose vinegar’ for headaches. Rose hips have a pedigree as preserves, jams and jellies, alone or mixed with honey or nuts. The value of wild rose hips was weighed and appreciated when in the 1940s citrus fruit imports – the main source of vitamin C at that time – were restricted. Hips of the wild rose were known to contain a high concentration of the vitamin and were collected assiduously (along with other herbs) by County Herb Committees. The extraction process was refined and the supply of the vitamin maintained, an effort well described from first hand experience by Ranson.

Elder

The elder Sambucus nigra is a fast-growing, pithy and light-stemmed, large shrub, reaching 2-3 m in height. Its stinking foliage contrasts with frothy, cream flower heads emerging in May-June and red-blue fruits that get picked by the birds, one by one, as they ripen later in the year. The stems grow to a few inches across and usually have a hole in the middle (centre inset below). Elder is from the same family as honeysuckle and wayfaring tree (neither in the garden at present).

The plant has many uses. The easily hollowed stems are reported to have been used as whistles. Flowers are edible – try elderflower pancake where the blossoms are dipped in batter and fried (Grigson) – and also make a flavouring for ‘toilet water’ (Ransom) and drinks. The ripe fruits make a jam or jelly or can be dried like currants. Most parts have medicinal properties (see Darwin for list). One of the most useful of hedge plants.

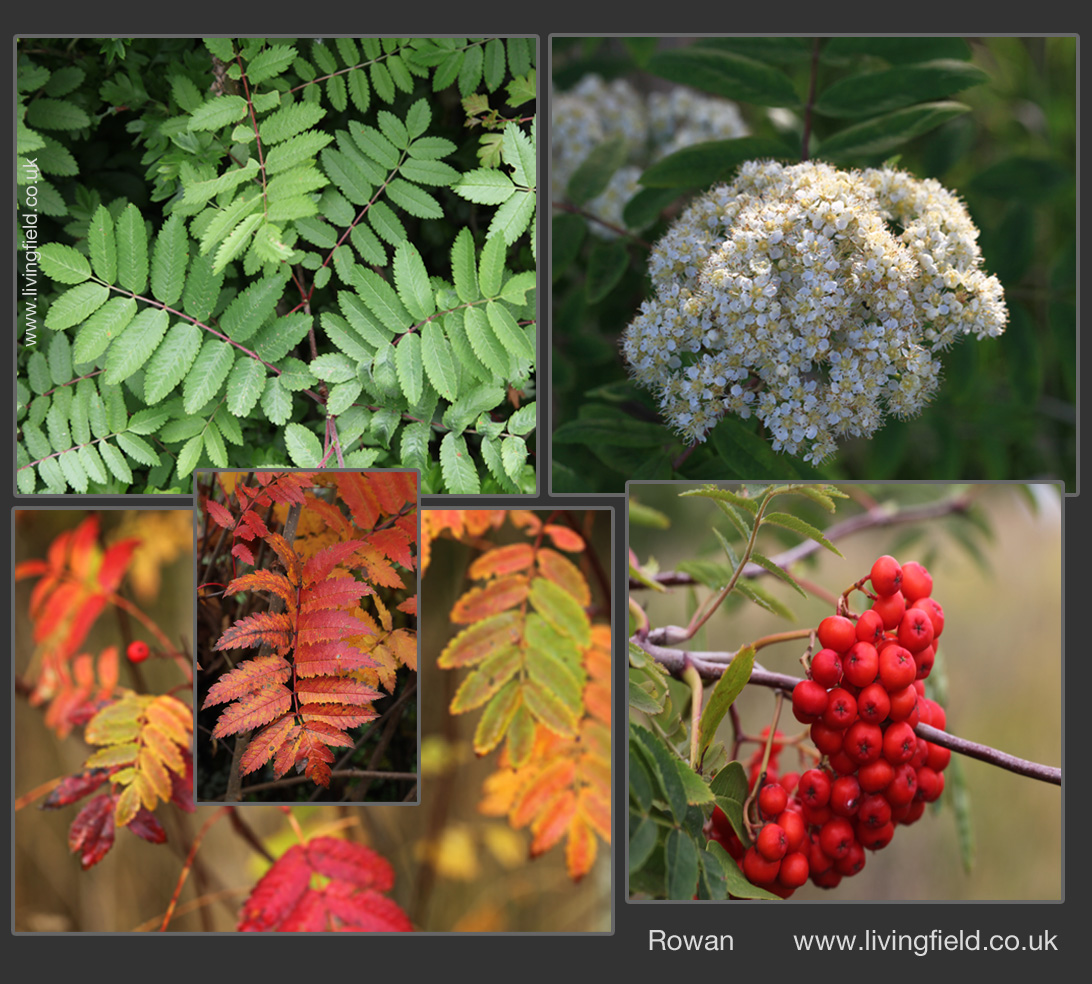

Gean, rowan and bird-cherry

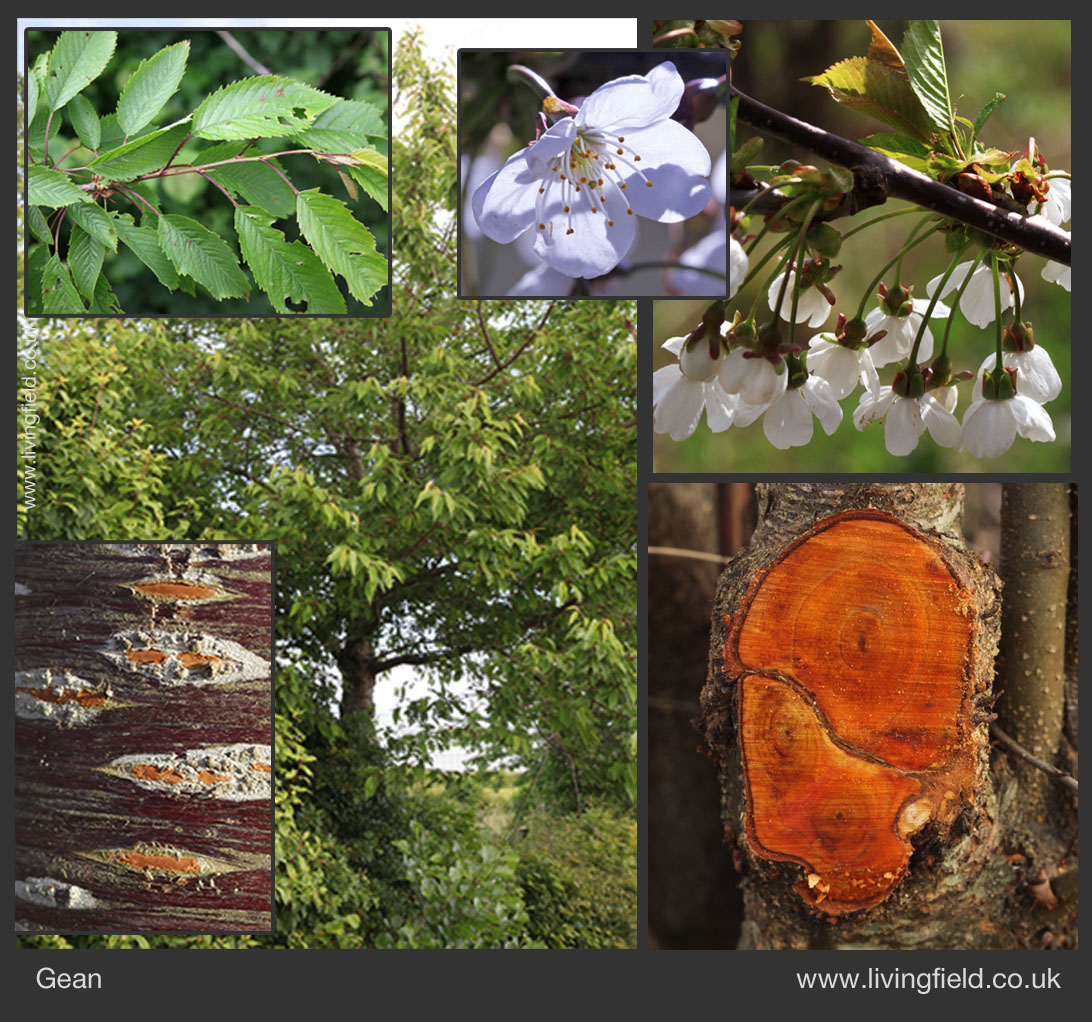

All three are of the Rosa family and all can attain the size of a medium-sized tree in the right location. In the Garden, they typically reach the height of a small cottage, but would be dwarfed by the large lowland trees.

Gean or Wild cherry Prunus avium has characteristic multi-coloured bark and white flower-clusters. When cut, the trunk and main branches show a bright russet. The cherries are red in autumn, sour of taste and used for cherry-brandy, but can be missed since wild birds quickly take them when palatable. Cherry-tree gum has some ancient medicinal uses (see Grigson for reference).

Rowan Sorbus aucuparia is perhaps the one small tree that – albeit with gean – best defines the croplands and the higher grazing lands. Sometimes surviving in a cut hedge, and not often comfortable below oak, ash and beech, it nevertheless stands out as a tree by form and colour and usefulness. The garden has one rowan tree but most others of the species live in the hedges, where they flower and fruit if left uncut for a year or two. The best known product is rowan jelly from the fruits, but they also give rise to a fermented drink and to dyes (Darwin).

Bird-cherry Prunus padus became uncommon as a self-seeded, wild plant in the croplands, but has recently been planted widely on waysides and roundabouts. It is not grown as a trees in the Garden, but in among the other cherries in the hedges, distinguished by bigger leaves and flowers held on short sub-branches.

Birch

Planted in the garden as a couple of small trees, birch has a characteristic whitish, peeling bark and small, almost diamond-shaped leaves that filter rather than block the light. Leaves that develop in the shade are deeper green and larger than those exposed to the sun and wind. It’s more at home in the higher croplands than with the tall oaks and ashes of the lowlands, yet birch can form a splendid woodland allowing many other plants to grow beneath its shade.

Other trees and shrubs

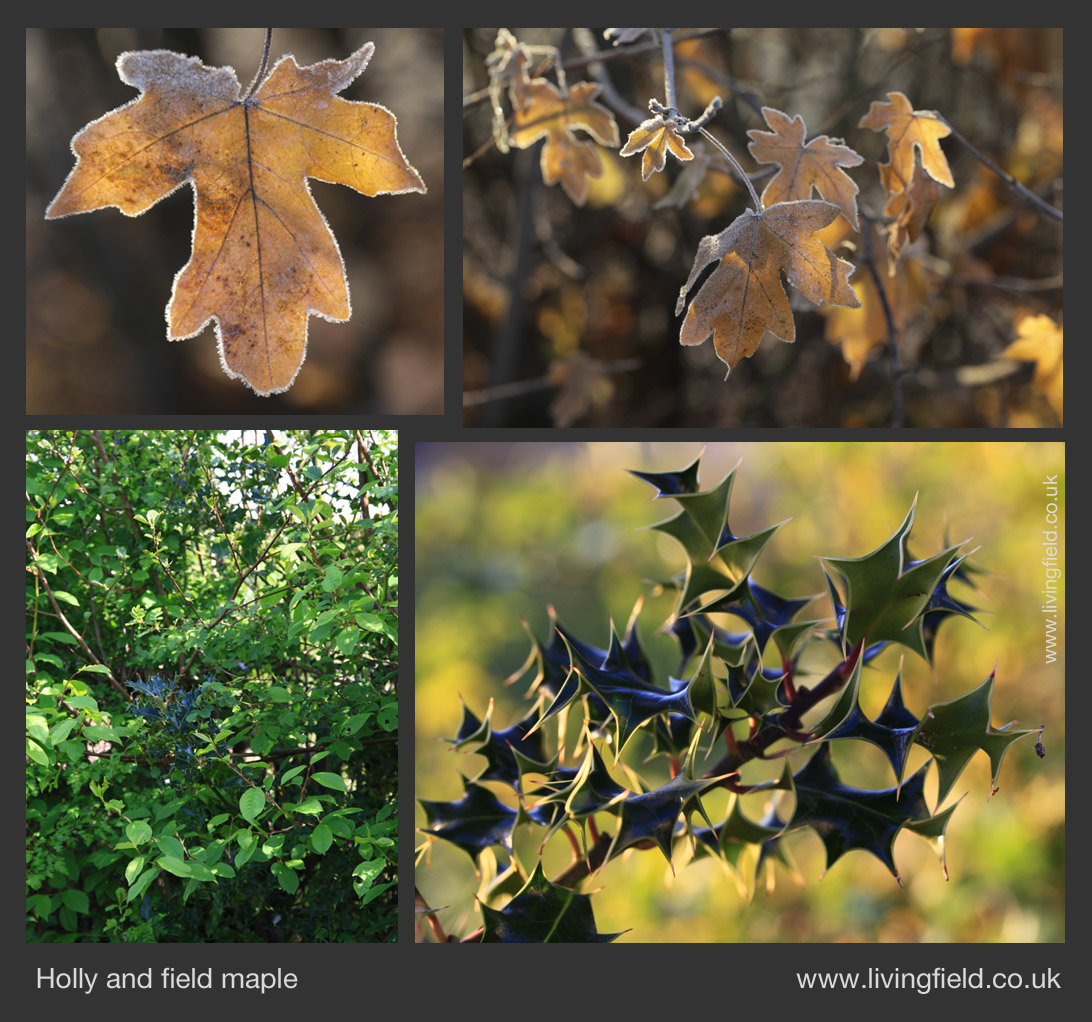

Holly Ilex aquilifolium is the only plant of the hedges to keep its leaves over the winter. And by keeping its leaves, so spiny and impenetrable, it offers space for small animals that seek a refuge. Holly is one of few plants – another is the stinging nettle – that have the sexes on different individuals, yet while they are cut short, the branches rarely flower; so a few individuals were left uncut to grow into small trees, to see if some would be female and produce berries.

A few plants of field maple Acer campestre were planted in the hedges. Its range is to the south of Britain where it can grow to a medium-sized tree. The panel above shows field maple leaf frosted in winter (upper), holly in hedge (lower left) and a holly branch.

Management

Mixed-species hedges were planted round the perimeter and along the divide between west and east gardens. They are part of the hedge network that permeates the farm. All hedge and tree species are local and were sourced from local, specialist nurseries. The plants were put in as as small ‘whips’ in 2004 and have since grown into large shrubs. They are cut back every few years to about 1 m in height, but usually one side at a time, so that the hedge retains some long, flowering branches and adequate shelter. Most species in the hedge will grow into trees if not cut back.

A few trees – alder, birch, hazel, wild cherry – were brought in as large saplings and planted in a clump to the east of the dividing hedge just north of the pond. Given the small area of the garden, tree species were chosen that do not grow to a great height and girth like the oaks, ash and beech.

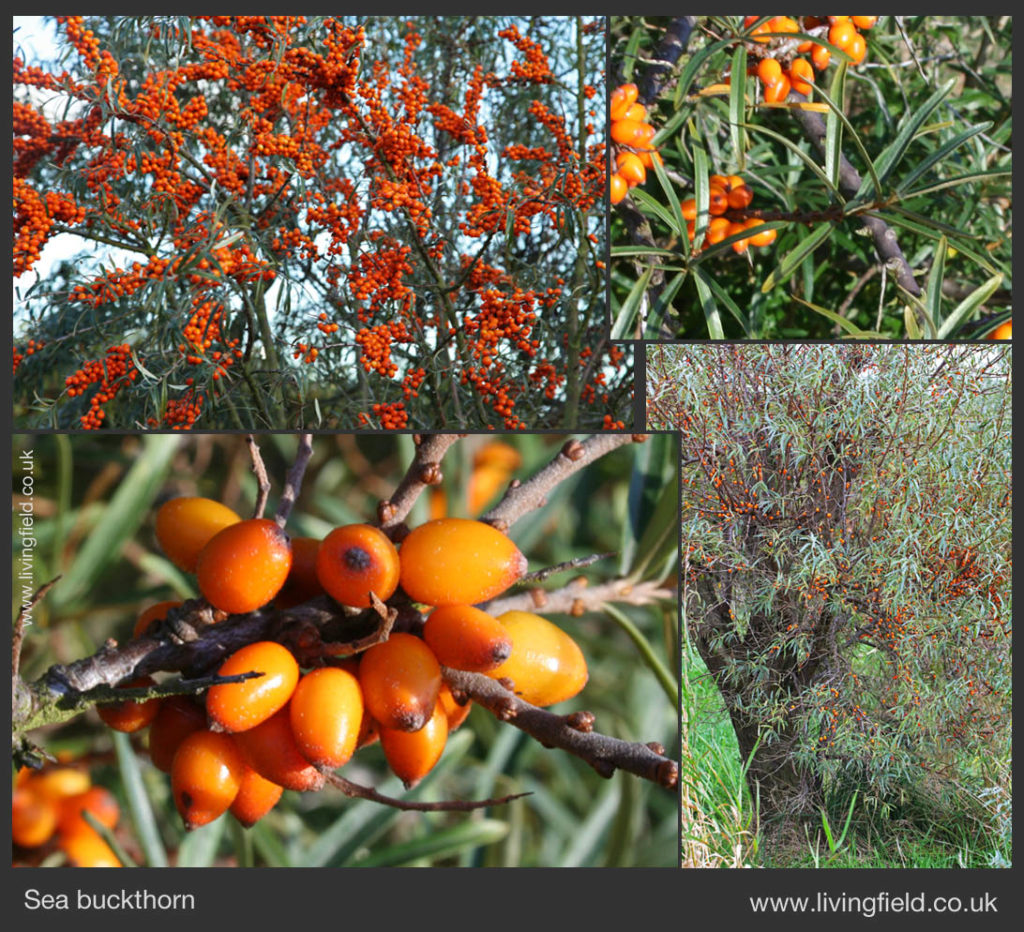

Some notable species are still absent: wild (crab) apple and wild pear among them, though one apple grows by the path from the Institute to Invergowrie village. Some honeysuckle needs to be planted. Sea buckthorn (photographs below) can be found, not in the garden, but along the path from the gate by the glasshouse and over the farm track.

Further sources

Tess Darwin’s The Scots Herbal, Geoffrey Grigson’s The Englishman’s Flora and the Dixons’ Plants and People in Ancient Scotland give many references to uses of the plants on this page. Florence Ranson’s British Herbs (1949) describes the organised collection and processing of wild rose hips.

Details of these and other sources, including web-links, are at the Medicinals and Dyes pages on this web site.

Web sites such as The Woodland Trust provide information on planting and management and also on foraging and use of products.