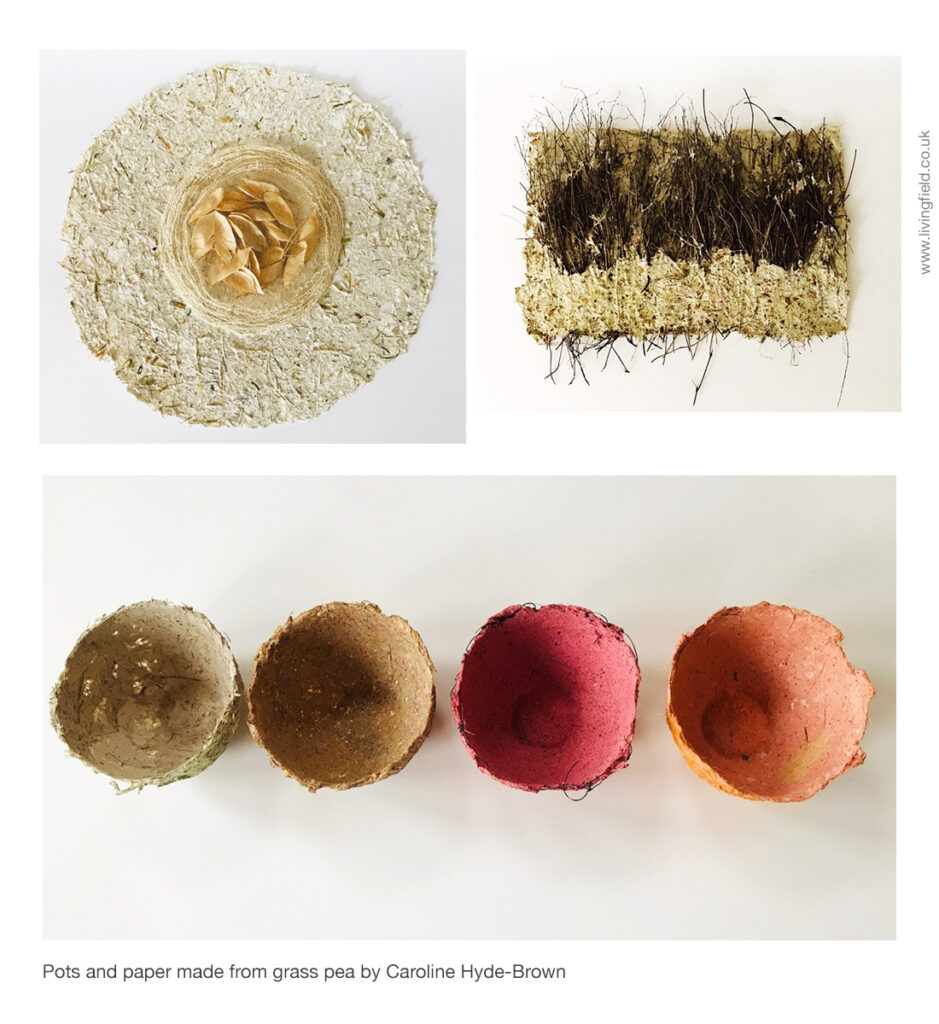

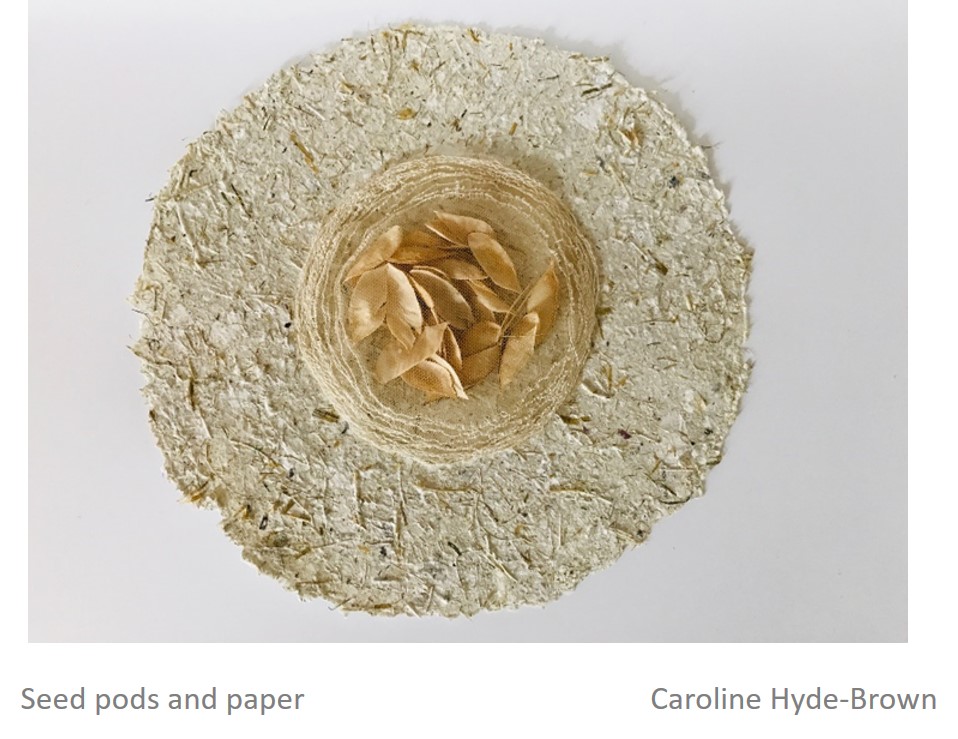

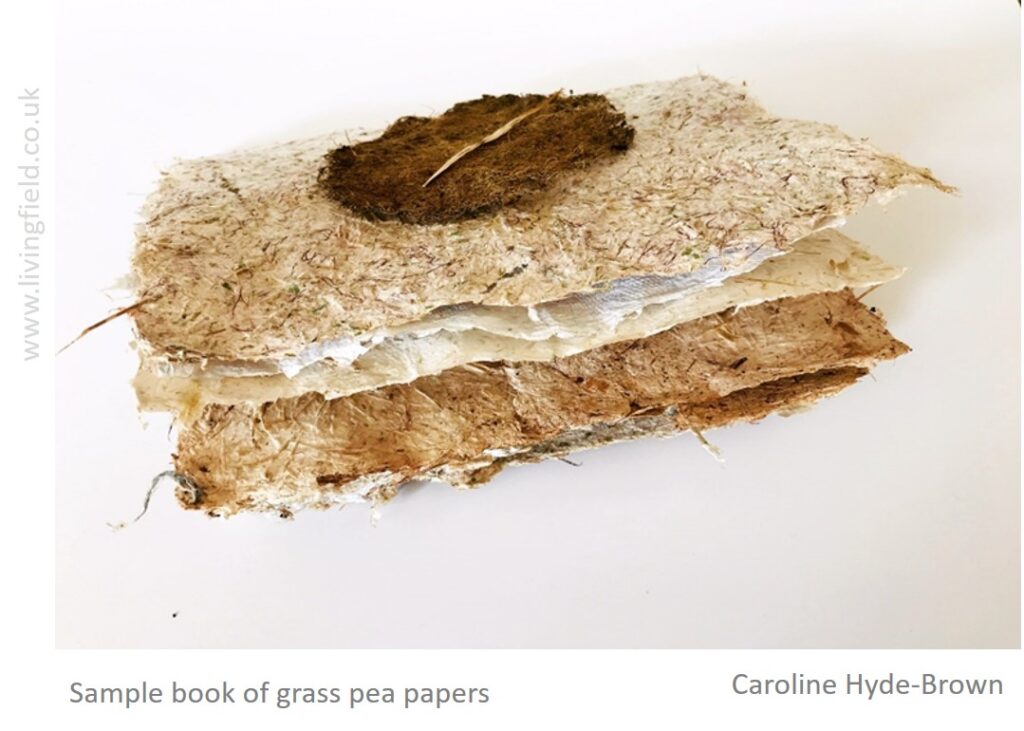

Here is another selection of handmade paper and a pot made from grass pea by Caroline Hyde-Brown. See how she does it at Repurposing grass pea …

sustainable croplands

Here is another selection of handmade paper and a pot made from grass pea by Caroline Hyde-Brown. See how she does it at Repurposing grass pea …

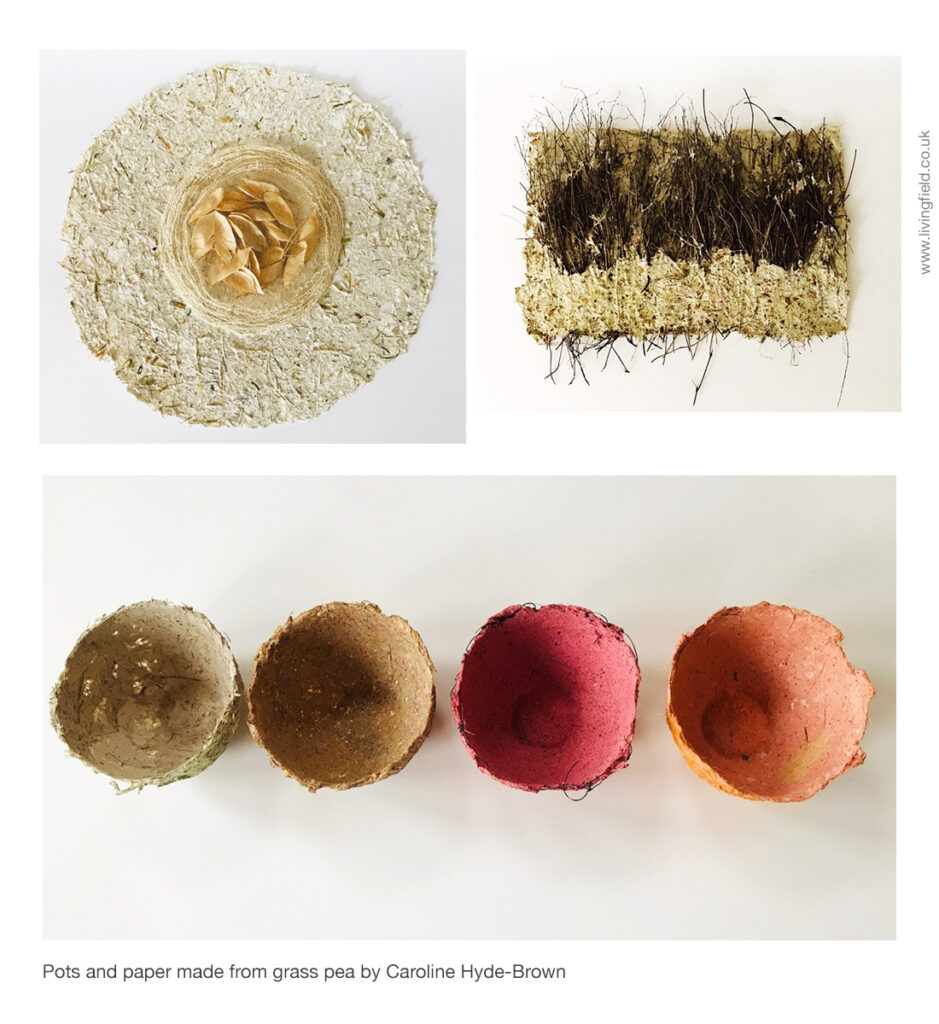

Caroline Hyde-Brown, at Norwich University of the Arts, gave the Living Field this account of her work with the legume, grass pea. Here are some examples of her craft.

Read on to see how it is done.

The grass pea Lathyrus sativus is a member of the legume family (Fabaceae) and commonly grown for human consumption and livestock feed in Asia and East Africa (Caroline writes). It is a hardy yet under-utilised crop and able to withstand extreme environments from drought to flooding. The grass pea fixes nitrogen from the air which helps maintain a healthy and well fertilised topsoil [1].

However, the grass pea contains a potent neurotoxin called B-ODAP which increases if the plant is exposed to conditions of severe water stress. Historically the grass pea is known to produce adverse side effects with excessive human consumption which exacerbates the risk of a neurological disorder known as lathyrism which can cause permanent paralysis below the knees both in adults and children.

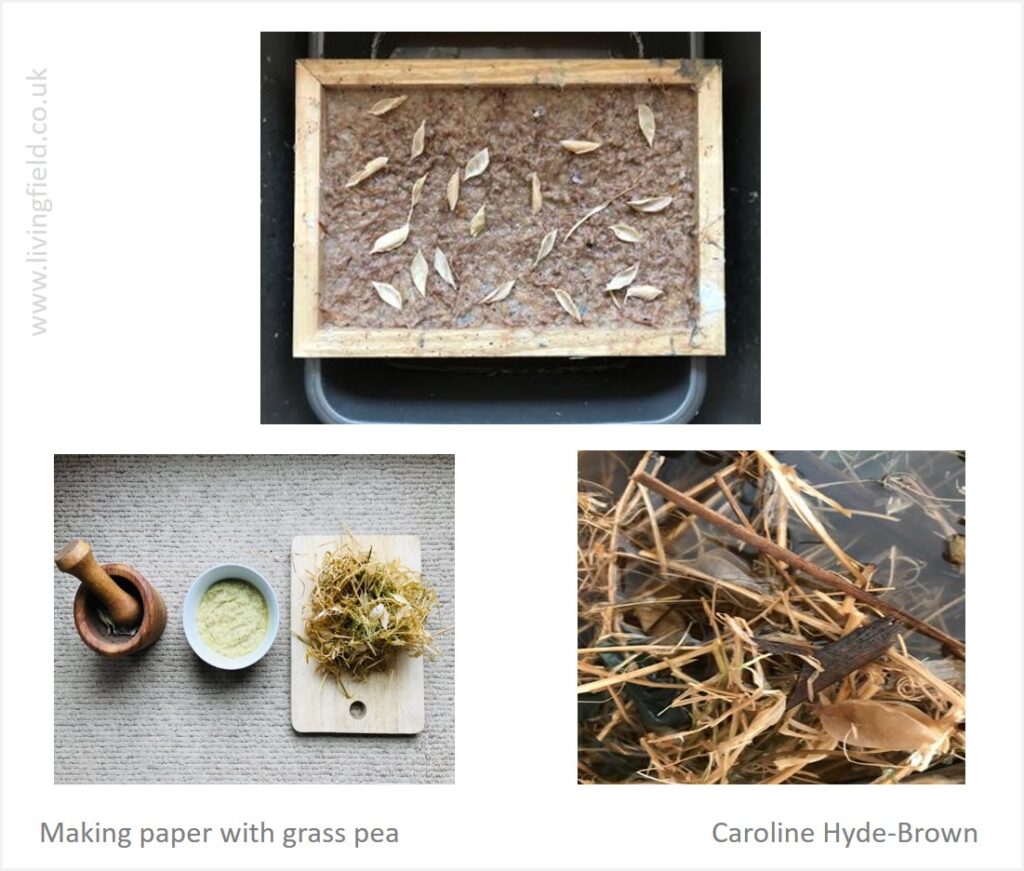

In September 2019 I initiated a collaboration with John Innes Research Centre in Norwich to investigate whether this ancient legume could be utilised to create a biomaterial with a sustainability strategy of raising its residual value. With a mixed methodology of qualitative research, critical inquiry, and home-based experimentation, I explored the inherent qualities of the natural raw plant residue with Anne Edwards and Abhimanyu Sarkar [2]. I used a framework known as the ‘whole systems’ approach adding freshly collected rainwater and solar heat [3].

I experimented with different types of potting containers to observe growth patterns and plant behaviour. Shallow containers produced spindly and weak plants compared to the much stronger and higher yielding plants grown in deep ‘rose’ containers or in a glasshouse.

My assistance with the harvest at John Innes yielded positive results during January 2020. I began with behavioural growth studies in agar flasks, which provided a fascinating insight into the delicate root structure as the roots are normally below ground. Unexpected discoveries about how the grass pea behaved under certain conditions helped the iterative design process.

During lockdown last year I had time to observe the plants on my windowsill and how they used the agar provided by John Innes. I didn’t need to water them, and it was fascinating to see how the plant easily grew, the perfect house plant!

I also planted some grass pea in different types of container with various depths to see which environment the crop preferred. The black container (photographs above, lower left) provided the wonderful patterned shapes shown lower right.

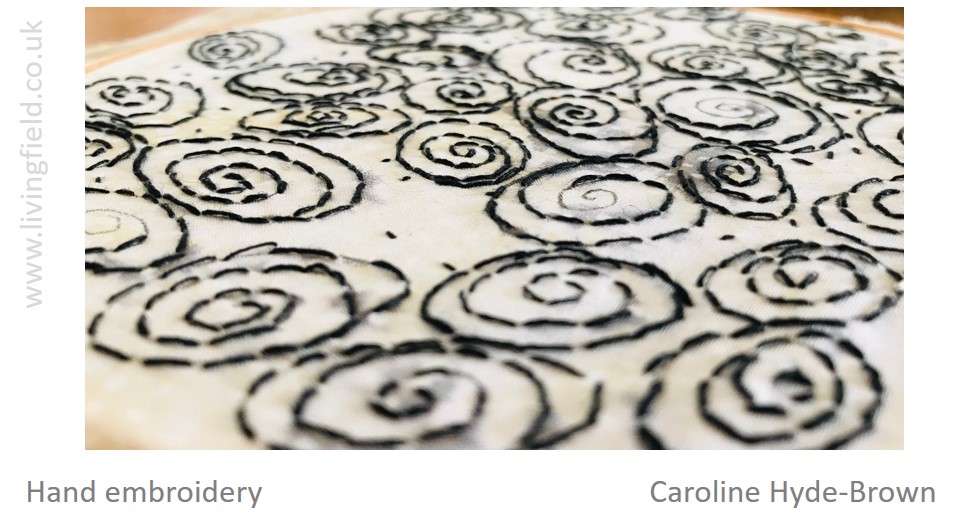

Perfectly formed tendrils from the harvested residue of grass pea inspired me to do some hand embroidery. I used Kantha stitching on cotton to reflect the Indian traditional embroidery technique of simple straight stitch.

My overall aim was to see whether the grass pea residue could be recreated into a cloth of some kind. Cutting up the paper samplers and using other threads and vintage lace slowly transformed the paper into a fabric, but the harvested residue was extremely dry and brittle.

I was unable to spin a thread out of the stalks. However, I believe, with the right biotechnology, cellulose could be extracted from the grass pea to make clothing, paper, shoes and lighting. Recent advances prove that using agricultural waste is an extremely profitable and sustainable operation with companies such as Agraloop [4], already spinning innovative and unique fibres.

Initially my papermaking explorations were unsatisfactory. The handmade paper felt stiff, broke easily and resembled cardboard. After boiling the residue and retting it in a bucket for a week however, it softened to produce a softer slurry or pulp.

Although I was unable to provide precise samples of artisanal stationery, each piece of handmade paper had its own individual character. I began to realise that imperfections can help create an authentic narrative and felt more confident in exploring other possibilities with ingredients.

A series of handmade papers were constructed from localised resources. I wanted to see if the grass pea could hold other grasses and petals within multiple layers of slurry. I took advantage of the warm weather and dried them in the garden. By adding spices from the kitchen, combined with grass clippings and petals taken from hedgerows and heathers they took on a lovely range of colours.

I also wanted to test some of the bio-resins from my collection of azeleas to see whether it added another material dimension. I looked at adding colour and referenced the pantone colour range for 2020 to provide inspiration for a moodboard of handmade paper.

Interpreting scientific knowledge and merging it with my own craft-oriented methods is a lengthy and complicated process. The bio pots initially started out as a conversation when I decided to see whether the knowledge I had gained through papermaking over the summer could result in something more tangible like a functional product.

I looked at whether the grass pea pots could be dyed to provide colour, starting with kitchen spices such as paprika and herbal tea bags with raspberry, blueberry, tea, and coffee. These were quite successful samples and ongoing observations are being made into the waterproofing and durability. Further growth studies will commence this year with a view to creating something that may offer a sustainable alternative for the tree planting initiatives overseas.

Research into the use of natural resources to provide extra sources of income has proven potential. It shows how the bridging of traditional artisan work with modern design can provide sustainable solutions. An essential part of the process includes rigorous testing of raw materials to demonstrate that the process is both restorative and circular from the beginning of the supply chain to the end product.

As an inter-disciplinary artist, I seek to implement new ideas through forming partnerships which help shape and question my own practice. I feel fortunate that we could build a strong professional network to bridge knowledge gaps. It was a collaborative process that reinforced our objective of helping to improve rural livelihoods in India.

I conclude that the grass pea supply chain could be disrupted from field to biomaterial and repurposed to provide vital ingredients for economic change.

[1] Caroline writes: “When all other crops fail, grass pea will often be the last one left standing. It is easy to cultivate and is tasty and high in nutritious protein, which makes it a popular crop. The Consultative Group on International Agriculture Research (CGIAR) states that at least 100,000 people in developing countries are believed to suffer from paralysis caused by the neurotoxin. More at the Crop Wild Relatives Project: The curious case of the grasspea.

[2] From the John Innes Centre web site, 27 May 2020: Paper making with grass pea.

[3] The “whole systems approach” was devised by a group of Product Design Students at the Iceland Academy of Arts in 2015 during a project using willow. They designed a unique range of products including paper, glue and string adding just heat and water.

[4] Agraloop: transforming low-value waste to high-value fibre.

[5] The Journal of Sustainability Education describes how collaborations beyond the comfort zone of specialist areas possibly hold the key to making unusual discoveries. Journal web site: http://www.journalofsustainabilityeducation.org/

email: artistcaz@aol.com

web site: https://www.theartofembroidery.co.uk/

The editor writes: Many thanks Caroline from the Living Field for sharing your experiences and experiments on grass pea. We hope you can continue to develop the technology and craft work and help to generate new income streams for growers.

For other occasional Living Field articles on the use of legumes, see Feel the pulse and Scofu: the quest for an indigenous Scottish tofu.

Caroline Hyde-Brown www.theartofembroidery.co.uk sent the Living Field these images of pots coloured with natural dyes and crafted paper, all made from the legume Grass Pea. More to follow ….

Latest from Grannie Kate …..

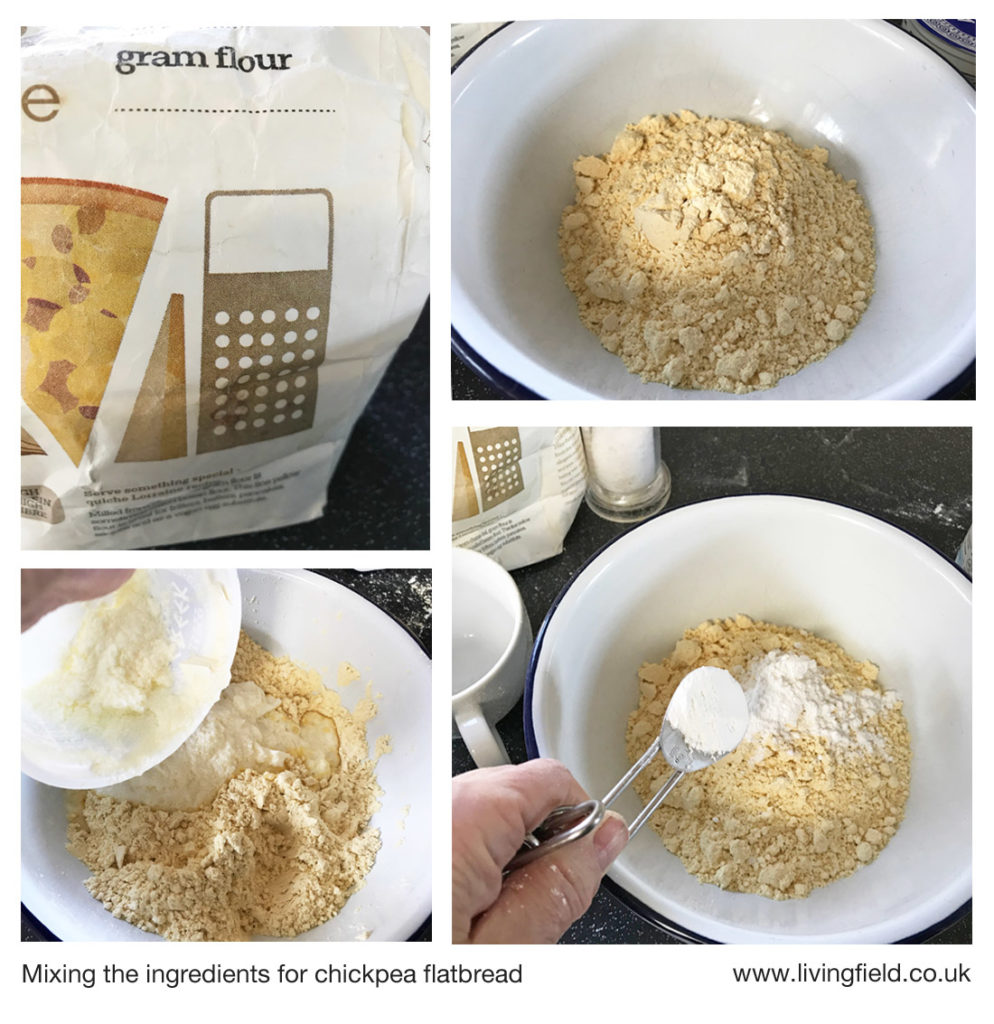

Flatbreads or bannocks made from oatmeal, beremeal or peasemeal are a traditional food of this region.

I decided to try and make some quick and simple flat breads to serve with soup, but instead of these I decided upon gram or chickpea flour. It’s a fine flour, yellowish in colour. Chickpea is a legume plant like pea, but usually grown in warmer countries.

Gram flour makes an excellent cheese sauce, by the way, for cauliflower cheese or a pasta bake.

These flatbreads are tasty, nutritious and filling. Keep them wrapped in foil and they will retain their freshness for a day or so.

Add a sprinkling of sesame seeds with a little oil onto the surface of your flat breads before frying them on the bakestone or frying pan. Or try cumin seeds in the same way.

[1] Gram flour is make from chickpea seeds Cicer arietinum – a legume plant grown in many mediterranean and tropical regions as one of the staple protein crops.

[2] For more on the history of flatbread country, see Peasemeal, oatmeal, beremeal bannocks on the Living Field web site.

[3] Like most legumes, chickpea fixes its own nitrogen from the air, so needs little if any mineral N fertiliser to help it grow and yield. Since mineral N is one of the main pollutants and sources of GHG emissions, growing and eating chickpea and other pulses is good for soil and the planet.

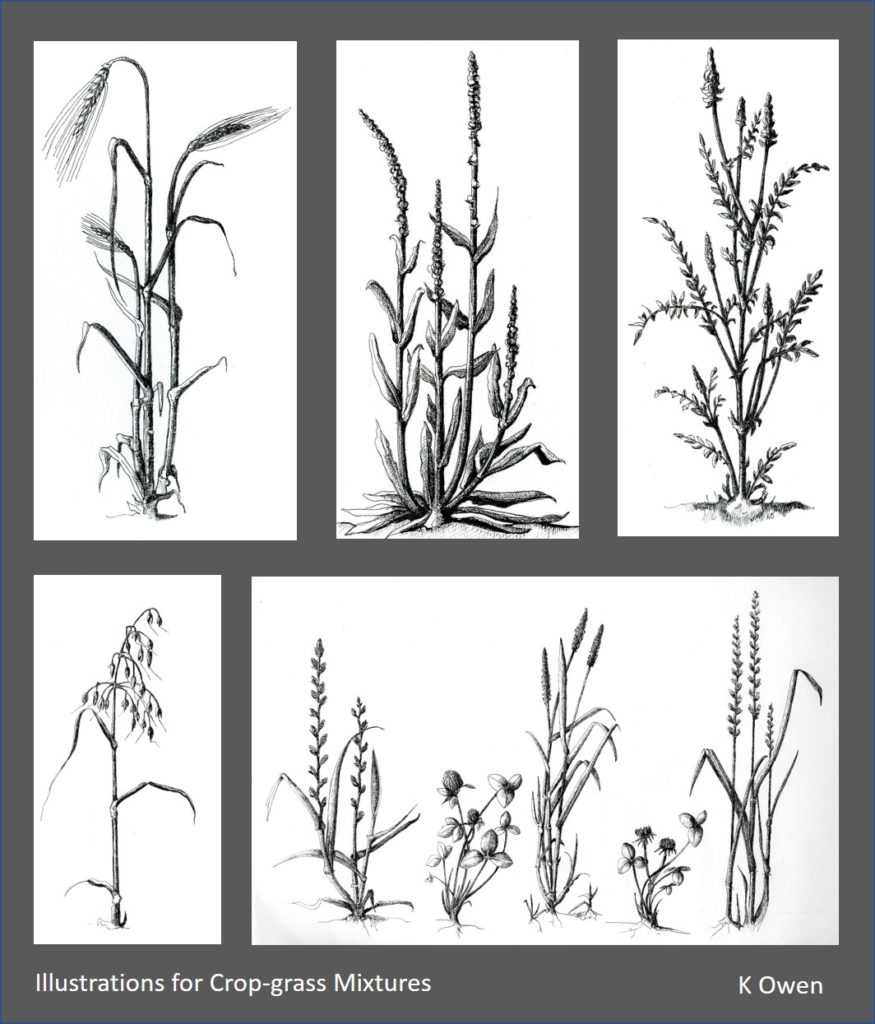

Mixtures sown for hay or grazing in the 1800s. Grass, legumes and other broadleaf plants selected for their ablity to live together. Many of the plants grown then coexisting now in the Living Field garden. Lessons for grass rediversification today. One of a series of articles on crop-grass diversification.

The run of bad weather, crop failure and hunger of the late 1600s, sometimes called ‘the ill years’, was one of the factors that led to a period of agricultural improvement from the early 1700s to the late 1800s. The improvements raised and to a degree stabilised food production. One of the most important developments was the design and trialling of species-rich plant mixtures for hay and grazing.

Early accounts of ‘grass’ mixtures by agriculturalists, notably Stephens, Elliot and Findlay, are valuable to us today because they gave weights of the seed of each plant species that made up the mix [1]. Though weight of sown seed does not translate directly into mass of the species in the field, it is the only measure handed down to us by which the diversity of those old mixes can be quantified and compared with today’s commercial seed mixtures.

Why is this important? Over the last 150 years, crop-grass agriculture has become less diverse, more dominated by a few grass species and in the process losing many ecological functions. Plans to re-diversify could learn from past practice.

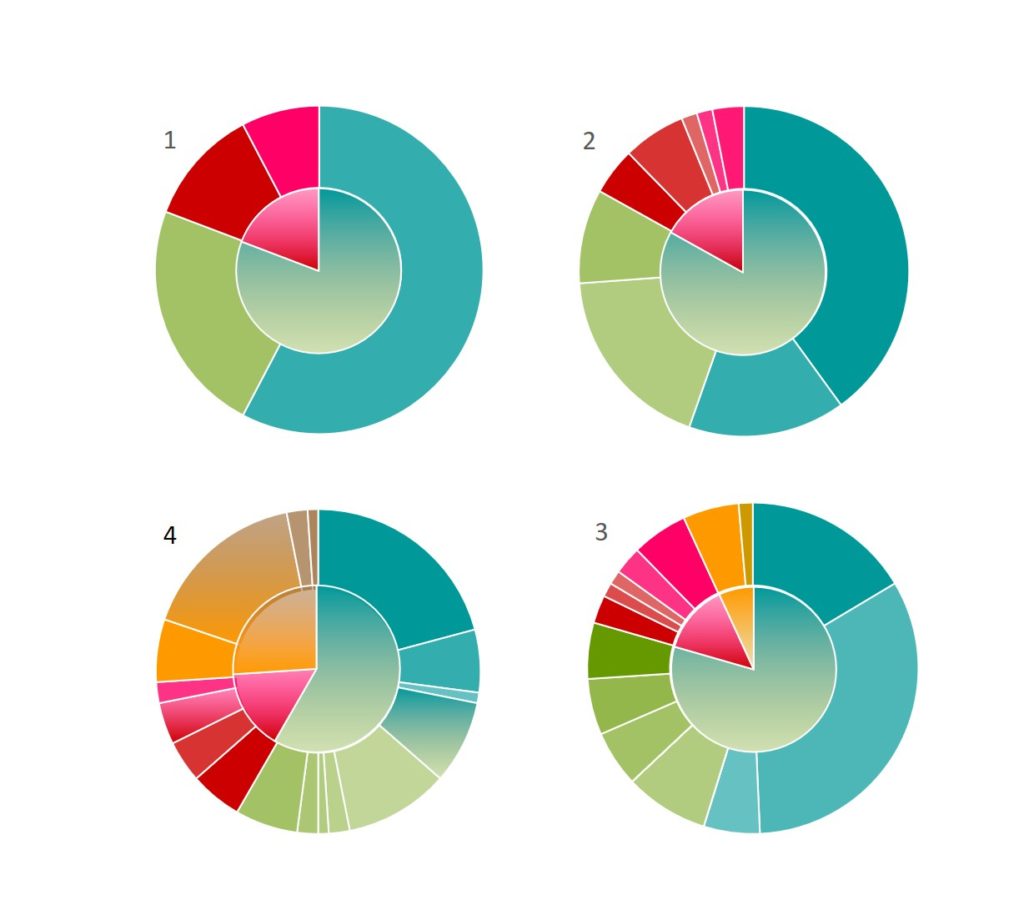

The hay and grazing mixtures from this period are summarised in a related web article [1] as circular diagrams, the inner ring showing the proportions of grass (blue-green), nitrogen-fixing legume (red) and, when included, other broadleaf plants (orange-brown), while the outer ring shows the proportions of individual species. The diagrams below show the rise in complexity of the mixtures from one-year-hay (1) to two-year grazing (2) and permanent pasture (3, 4).

The main feature of those mixes – though rarely seen today in commercial grass fields – is the presence of several legumes species and sometimes broadleaf plants other than legumes. The role of the legumes is to fix nitrogen gas from the air and so enrich the soil for the grass species at a time when mineral fertiliser was not widely available. The other broadleaf species were included to fill ecological gaps (functions and processes) that could not be provided by the grasses or legumes.

The meadow in the Living Field garden [2] was sown back in 2004. In the first few years, the most visible plants were those that grew quickly and flowered in the first or second year. These annuals and biennials were soon ousted by perennials, some that had been sown and others that came in. After 5 or 6 years the meadow was populated by a diverse group of perennials.

The meadow has been lightly managed – cut once a year, usually in September. Yet many of the plant species that were part of the 1800s mixtures appear naturally able to coexist in the meadow and surrounding patches.

The typical legumes in early grass mixtures were clovers, the red and white species but also alsike and several others. Red Trifolium pratense was thought best for one year’s hay because it was fast growing but short lived, while white Trifolium repens persisted much longer and was suited to pasture. Both have lived in the meadow for at least a decade. Alsike Trifolium hybridum was grown as part of a legume collection a few years ago but has not remained.

Other legumes in sown mixtures from the 1800s included the bird’s-foot trefoils, mainly Lotus corniculatus which is as common in the meadow as white clover, and kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria which persists as only a few plants here and there among the grasses and sometimes in the medicinals bed.

The meadow has other legume species, of the genus Vicia, that were not generally favoured in earlier mixtures because they have tendrils and so tend to twine among and drag down the grasses and other plants.

Two common tendril-bearing species recur in the meadow each year – common vetch Vicia sativa which generally keeps to itself and hairy tare Vicia hirsuta which can become a serious weed (as this year) smothering other plants. A third one of this type, tufted vetch Vicia cracca tends to move around unkempt patches rather than live in the meadow.

The images in the legume panel above show (top left, clockwise) white clover among grass and plantain, common vetch, kidney vetch and red clover with bird’s-foot trefoil (yellow flowers).

It may come as a surprise today to learn that plants other than grasses and legumes were purposely sown in fields as part of mixtures for hay and pasture. Of those reported from the 1700s and 1800s, the commonest in the meadow itself are yarrow Achillea millefolium and ribwort plantain Plantago lanceolata.

Two others have appeared in grassy areas – chicory and burnet. Chicory Cichorium intybus was first planted in the medicinals bed, but has spread and now lives among grasses such as yorkshire fog and cocksfoot. Its main role in the 1800s mixtures was to break through soil pans that formed at 10-20 cm depth due to the shallow ploughing that was typical of the time.

A few plants of burnet Sanguisorba minor were noted a some years ago, and like chichory have persisted for years among competitive grass species. We do not know where the burnet came from.

The images above show (top left, c’wise) burnet and ribwort plantain among grasses, yarrow leaf, chicory plant with blue flower inset, burnet leaves and red stems. and finally ribwort plantain with flower inset.

They might ‘all look the same’ in leaf, but their basic floral structure recurs in many forms to give great diversity among our common grass species. Many of the early sown mixtures included timothy-grass Phleum pratense, cocksfoot Dactylis glomerata, crested dog’s-tail Cynosurus cristatus, several fescues (Festuca species) and tall meadow-grasses (Poa species), all of which are present in the meadow.

Two other pasture grasses are common in the garden – sweet vernal-grass Anthoxanthum odoratum and yorkshire fog Holcus lanatus which become established wherever the ground is left untilled for a few years.

The grass panel above shows (top left, c’wise) mainly yorkshire fog growing among wild carrot, flowering heads of sweet vernal and timothy and (from the early years) fescue and crested dog’s-tail among ox-eye daisy.

The 1800s mixtures were designed to give a balanced diet for livestock and to ensure fresh plant tissue was present for a long as possible during the year. They mixed species to ensure that each came to prime leaf or seed at different times. For hay, the progression of floral or reproductive structures was important, for pasture the blend of leafy parts.

The meadow in the Living Field garden also harbours other plants sown specifically for wildlife, including field scabious, perhaps the favourite of the pollinating insects, ox-eye daisy and lady’s bedstraw. At one time wild carrot lived in the meadow (top left in the grass panel above) but now prefers grassy margins next to paths. Even with these additional species, the meadow complex retains many of the species sown for hay and pasture from the 1700s to the early 1900s.

The secret of sustaining the meadow is to keep soil fertility low by not fertilising and ground cover high by growing many species that quickly react to fill any gaps. No one species dominates and noxious weeds are given little chance to enter.

[1] The original sources, mainly Wight (late 1700s), Stephens (1841 onwards), Elliot (1898 onwards) and Findlay (1925) are given in this companion article: Grass mix diversity a century past on the curvedflatlands web site.

[2] The origin, main species and management of the meadow are described on this web site at Garden/Meadow and Garden/The_making. The drone image below from early 2019 shows the location of the meadow (covering about 200 square metres), see also : Living Field garden from the air.

The Living Field team has maintained very high diversity per unit area here for almost 15 years.

Contacts: this article geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk; meadow management gladys.wright@hutton.ac.uk.

What a great day, 9 June! Yet another successful Open Farm Sunday at the Hutton Dundee. Crowds of visitors enjoying themselves in sunny weather. The Living Field garden did its bit as before – exhibits on barley and legumes in the polytunnel, potato varieties in the west garden and further science exhibits in the cabins.

Our friends from Dundee Astronomical Society were here again showing people round the new observatory and explaining about the sun, moon and noctilucent clouds. And this year we were helped for the first time by a workshop on cyanotype imagery run by Kit Martin.

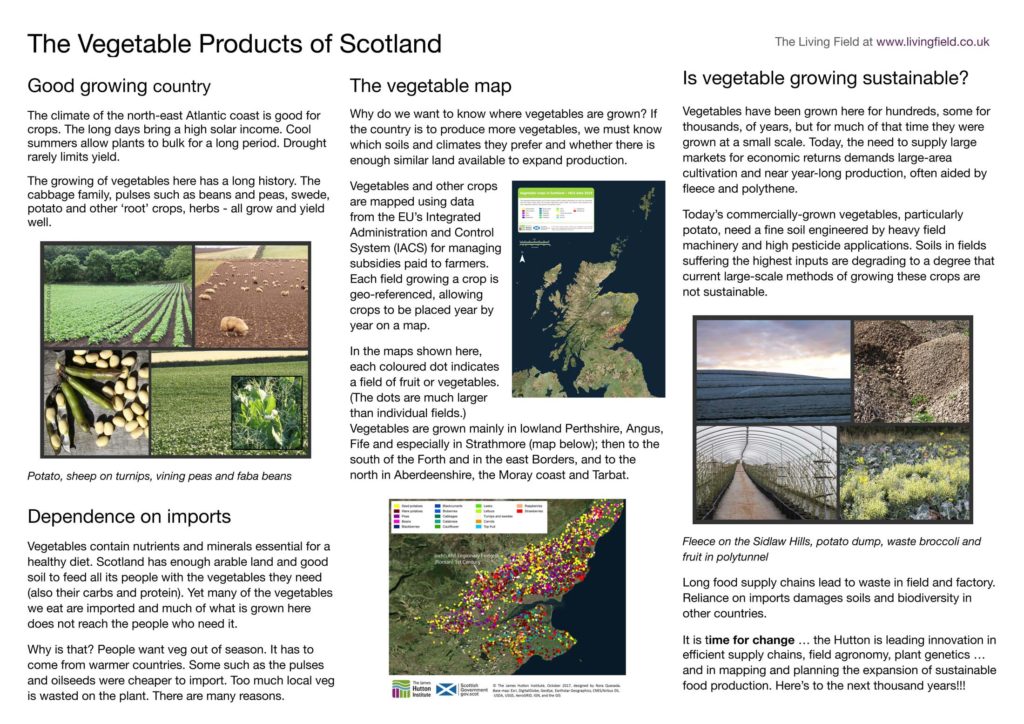

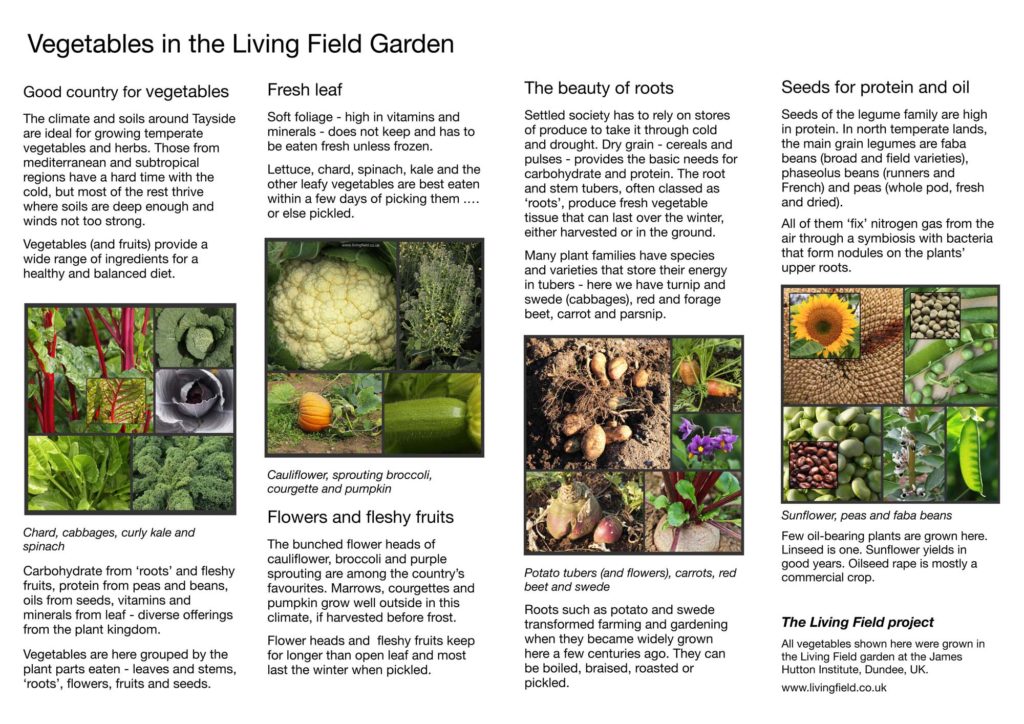

The centrepiece was the new Vegetable Map of Scotland, shown top left and centre in the panel above. For more on how it was made, see Vegetable map made real. The map occasioned much comment and wonder that the country was already growing such a wide range of vegetables and could grow much more of its own.

The two posters located next to the Vegetable map are available to view or download here.

One of the posters – The Vegetable Products of Scotland – explained the background to the original Vegetable map which was first shown at Can we grow more vegetables? The poster is reproduced below as a low resolution jpg image. It is also available as a pdf file printable up to A3 size.

Click for an A3 size pdf of the Vegetable Products of Scotland.

The other poster – Vegetables in the Living Field garden – showed many of the vegetables typically grown in the garden, grouped into leaves, fleshy fruits, roots and seeds. More on the plants can be seen at the garden pages under Vegetables. This poster is also reproduced as a jpeg below and available as a pdf.

Click for an A3 size pdf of Vegetables in the Living Field garden.

Contacts for Living Field activities: gladys.wright@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

Open Farm Sunday was a joint effort between The Farm, science staff, the events team, the Living Field community and many others.

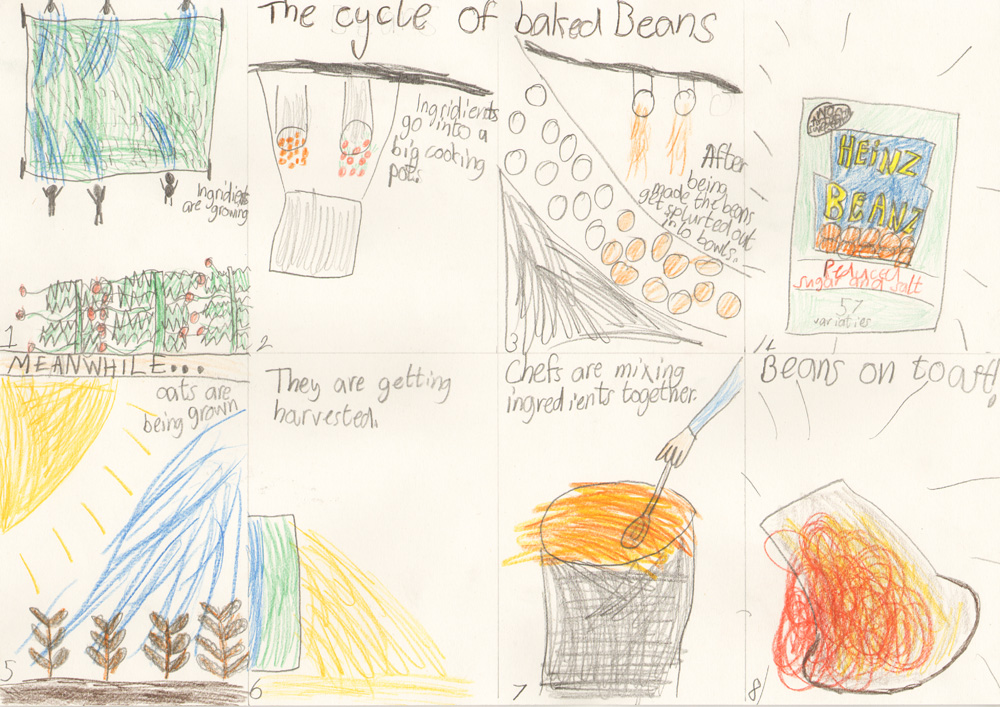

The famous Beans on Toast Project was started 7 years ago by student Sarah Doherty and artist Jean Duncan with Geoff Squire and other members of the Living Field team [1]. The project looked at the origins of this seemingly simple meal.

Not so simple in fact – 10 crops, grown in four continents and using masses of water and other precious resources – the product of a highly complex supply chain leading to a tin, a packet and a tub.

This example of the worldwide growing and sourcing of products that go into the food we eat has been used many times by the Living Field, most recently at a Citizen’s Jury event at the Scottish Parliament in March.

Sarah’s been reflecting on the project. She writes –

“Seven years on, I look back at the ‘water footprint’ for the Beans on Toast project as an eye-opening experience!

It was a reminder that there is a story behind everything. Almost everything we eat has travelled a long way to get on our plates. For so much water to go into the humble beans on toast – it baffles me how much more water and effort goes into producing other things.

I recently took up sewing and have been struck at how expensive it is to buy material for making home-made clothes. When mass- produced for high street stores, clothes may seem easy and cheap. However, making material is an energy and water intensive process too often involving crops for fibres such as cotton and linen.

I’m certainly more mindful of this now which is why I’m learning to cut my wardrobe down to what I really use and like the most!

Geoff was asked to attend a Citizen’s Jury as a specialist assisting the Jurors with background information on the topic being considered.

He used the Beans on Toast example [2] to show, first, that much of the food we eat is not grown here but imported, and second, that most of our pre-prepared food is made from mixing the products of many different crops grown using the resources of other countries.

Beans on Toast relies on haricot bean, tomato, oil palm, soybean, wheat, maize, sugar cane, paprika, onion, and oilseed rape ….. and that’s just the main ingredients. And the food on one plate of it needs several bathfulls of water.

Beans on Toast is an excellent example to show that we need to use less of other countries’ resources and more of our own.

What’s known as the legume gap or protein gap – the difference between home grown and imports – is massive. We grow just a few percent of the plant protein needed for feeding people and farm animals.

We have been adding to the information on sourcing food and estimating how much water and nutrients it takes to grow and process food like this [3]. Beans on Toast lives ….

To see the original pages –

[1] Sarah was studying at Durham University when she worked at the James Hutton Institute for about a year in 2012 . She has kept in touch. She last visited in summer 2018. Jean Duncan, who worked with Sarah on educational projects with local schools, still works with the Living Field.

[2] The Citizens Jury event was held at the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, 29-31 March 2019. Information at the curvedflatlands web page Citizens Jury at the Scottish Parliament.

[3] The EU TRUE project runs currently, coordinated at the James Hutton Institute. Among its aims is to study the global food and feed supply chains, to cut waste and and to raise local production. It’s full title is Transition Paths to Sustainable Legume-based systems in Europe https://www.true-project.eu

Contact for this page: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

Want to help stop the widespread decline of bees and other airborne insects? Here are some notes on the Garden’s plants most visited by bumble bees, hive bees, hoverflies and the occasional butterfly. Most of these plants are easy to grow.

One of the main aims of the Living Field garden is to allow native cropland plants some space away from weedkiller treatment and competition with crops. Recent scientific reports have drawn attention to the widespread loss of invertebrate life and insect life in particular. The declines are happening all over the world.

Everyone who owns or manages land can do their bit to support flying insects. Here we show some of the Garden’s plants and plant groups that have offered food and shelter to flower-visitors over the years.

The legumes (family: Fabaceae), just ahead of the Composites, are the single most important group supporting wild flyers. The legumes as a whole offer probably the greatest variety and longest flowering season of all plant groups in the garden. They fix their own nitrogen from the air. All parts of the plant are high in protein.

Sainfoin, the melilots and lucerne were once grown or tried as forage crops in Scotland. The clovers, mainly white and red, are still sown, but the red is more commonly seen in the wild. The bumble bees’ favourite of them all is the blue-flowered, tufted vetch (lower images in the panel) – its strings of flowers produced for months on indeterminate sprawling and clinging stems.

Next are the composites (family : Asteraceae), each flowering head consisting of many individual florets. Not all species are equally visited, but the best here for pollinators are thistles and knapweeds. The great cotton thistle grows like a small tree, supporting large heads several centimetres across, bumble bees often bustling two or three to a head.

The greater and common knapweeds, hemp agrimony and tansy shown above are perennials, whereas the thistles in the garden tend to be biennial – germinating one year, overwintering as a rosette and flowering the next. The weedy perennial creeping thistle is too invasive in the garden’s small space and though it supports insects is discouraged in favour of other thistles.

Of all the species in the garden, field scabious (family: Dipsacaceae) is the one that offers sustenance to flyers for the longest period. A perennial, growing mainly in the meadow, plants put out flower after flower from early summer to late autumn (except in the very dry 2018). If there was one plant that we could grow for the bees, it would be this.

Teasel is a close relative that also grows well here. It self seeds and is mostly biennial. Plants are moved at the rosette stage in autumn or early spring to form clumps that flower in the medicinals bed.

The labiate family (Lamiaceae), including mints, sages, woundworts, deadnettles, hempnettles and basils – are well represented among the medicinals and herbs. They grow in sun, in shade and as occasionals anywhere. The large flowered types such as the herb sage are most frequently visited by the Bombus species, while betony tends to attract more of the smaller carder bees.

The smaller flowered species, such as meadow clary (a perennial n the meadow), fields mints, hempnettle and wild basil are less attractive to larger flying insects but have their own specialist range of inverts.

These are not the only plants that offer food and shelter for flying insects. Among the first in the year are the flowers and leaves on the garden’s native trees and shrubs. Early summer in the hedges, flowers of wild roses offer a welcoming landing platform for grazing hoverflies.

One of the longest flowering species, not shown here in the photographs, is viper’s bugloss Echium vulgare, one of the borage family. (See it at the Bee plants links below.) Borage itself and the comfreys are also well visited.

Populations of bees and other flower-visitors were very badly affected here by the dry 2018. There was little left in flower by the end of August, while in most years the field scabious and viper’s bugloss are still visited in late October.

The coming year’s weather is uncertain as always, but we’ll try to manage the plants to give the longest possible season to the resident insects and spiders. First out will be the willow ….. .

Nearly all the plants referred to here are native species or ones introduced long ago and now naturalised. Very few of the crops grown in the region (and the garden) – barley, wheat, oats, peas – support or need pollinating insects.

Oilseed rape fields provide a crop-based source of food for a few weeks early in the year and field beans also offer high-protein flowers much later. But the main sown crops and leys that could provide the right seasonal habitat – the legume forages and grass-clover mixtures – are rare and mostly long gone.

In the broader landscape therefore, the main source of food for flying insects lies in the broadleaf ‘weed’ species that live in crop fields and disturbed margins – in fact most of those shown in the panels above belong in this category. These arable plants, mostly not injurious to crops, have declined over the last century to the point where many of the plants themselves are now rare. It’s no wonder insects apart from pests are having a hard time in cropland.

The Living Field’s page on Bee plants give further notes and images of the individual species most frequently visited in the garden.

As usual, the plants are grown and tended by Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson with help from the farm.

The photographs of the insects on field scabious were taken by Linda Ford on an ideal summer day a few years ago, the others by Geoff Squire. Colleagues from the farm cut the Living Field meadow once a year and trim the hedges in sequence every few years to allow flowering and fruiting (e.g. for roses, willow, hazel).

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com

The mixed cereal-pulse crop known as mashlum. Decline after 1950 yet still grown in a few fields. The question of crop mixtures in prehistory.

An earlier article Mashlum – a traditional mix of oats and beans [1] suggested that the mixed cereal and pulse crop known as mashlum had died out in Scotland but no ….. an email from a farmer in Fife, Douglas Christie, confirmed that it was still grown on his farm. Here is a photograph.

Earlier we had related an account from 1925 [2] on the difficulties of growing mashlum and also the benefits. Mr Christie reports that the mixture worked very well, that chemical and nitrogen fertilizer costs were drastically reduced, but that he had to pick the field carefully as some weeds would be difficult to control.

He also overcame some of the problems in sowing and harvesting a mixture reported in earlier accounts from the 1920s. He has a drill that can sow (direct drill) the two crops at the same time and a grain dresser that can easily separate the two crops after harvest,

Since hearing from Douglas Christie, the Living Field has noticed on Twitter that several farmers in the south of the UK are also working with mixed cereal-pulse crops. A further question arose in correspondence as to their antiquity.

That mashlum merited a separate chapter in the 1925 Farm Crops [2] shows how seriously it was taken. It first appeared in the agricultural census [3] under the heading ‘vetches, tares, beans, mashlum for fodder’ between 1902 and 1919. The category in the census then changed slightly to ‘vetches and mashlum for threshing’ which declined to a low point in 1939 (grey symbols in Fig. 1). Presumably the need for fixed nitrogen during shortages caused vetches and mashlum to increase in area almost 10 times during the war years.

Most of this increase was in mashlum, which in the 1940s and early 1950s became the most widely grown legume crop in Scotland – covering more area than beans and peas – and was listed in the census simply as ‘mashlum for threshing’ (orange symbols in Fig. 1) , that is, grown and harvested for seed. After a few years, it declined again in the early 1950s and had almost died out by 1960. In 1961, mashlum disappeared from the census and any remaining fields were combined with ‘other crops for stockfeeding’ (green symbols to the right of the trace in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The area sown with mashlum and related crops in the agricultural census in Scotland, 1902-1978 [3]. Mashlum was listed as a separate item in the crop census from 1944 to 1960 (orange). Before that it was part of ‘vetches, tares, etc.’ up to 1919 (light blue-grey), then vetches and mashlum for threshing (grey). Any crops remaining after 1960 were counted as part of ‘other crops for stockfeeding’ (green symbols).

The period from the late 1950s to the 1980s was the time of rapid increase in the use of mineral nitrogen fertiliser. The cereal-pulse mix became uneconomical.

Despite its temporary revival in the 1940s, mashlum, as all other legume crops, was grown on a small part of the arable surface in the 20th century, generally less than 1% of it.

A question then arises as to how old is the practice of sowing mixed cereals and pulses. The Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue (DOST) finds that mashlum, in the spelling mashloche, was in use more than 500 years ago [4], but that in itself tells little of the crop’s ancestry. Was the method handed down from earlier Bronze or Iron Age farmers to the medieval period or was it brought over by the Romans or early Christians?

The archaeological record in the north of Britain is thin on peas and beans: there is one record of field beans in Scotland – also known as horse bean and Celtic bean, now faba bean. Peas and beans appear far less frequently than cereal grains, but this difference is often attributed to the methods of cooking them: beans are less likely than grain to be charred and hence preserved. In an authoritative survey beans and cereals were examined in 75 locations in southern England [5].

At some archaeological sites, beans and cereals, such as emmer wheat, are found together and in numbers that suggest they were both grown as crops for food. Descriptions of the finds at Foster’s Field, Sherborne in Dorset for example, include the line that beans ‘may have been grown as a mixed crop with barley or as part of a crop rotation system’ [6], a statement repeated in the broader survey [5].

The archaeologists agree that presence itself does not mean anything definitive about how the crops were grown – whether alone, in broadcast mixtures, or in rotation or sequence. It is not hard to imagine, though, that cereal-pulse mixtures have been used from the earliest times. Imagine a household or village had some cereal and some legume seed, not enough to be sown alone, but together they would make a field.

And the same farmers would have known, as all farmers up to the mid-1950s have known, that cereal and pulses together do better on poor soil than cereals alone because of the nitrogen-fixing ability of the pulses, and if the pulse is faba bean, then also the support offered by the stronger bean stem.

Common sense tells that they would have grown mixtures but there is no definitive evidence.

[1] Mashlum – a traditional mix of oats and beans posed some questions about the crop grown as a sown mixture rather than a line intercrop.

[2] O’Brien DG. 1925. The Mashlum Crop. In: Farm Crops, edited by Paterson WM, pages 297-302, published by The Gresham Publishing Company, London.

[3] Crop census records for the main crops from early in the century to 1978 are available online as Agricultural Statistics Scotland from the Scottish Government web site at Historical Agricultural Statistics. Mashlum is sometimes included with other pulses and forages but is given as a separate crop for the period indicated in Fig. 1 above.

[4] DOST Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue cites the crop in the spelling mashloche from the 1440s at http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/mashloche.

[5] Treasure ER, Church MJ (2017) Can’t find a pulse? Celtic bean (Vicia faba L.) in British prehistory, Environmental Archaeology, 22:2, 113-127, DOI: 10.1080/14614103.2016.1153769. An excellent paper on the occurrence of field bean in Britain.

[6] Jones J. (2009) Plant macrofossils. In Best J, A Late Bronze Age Pottery Production Site and Settlement at Foster’s Field, Tinney’s Lane, Sherborne, Dorset. Archaeology Data Service 2009: idoi:10.5284/1000076. Many of the source papers on the topic are only available free to academic data services, but this one is available online through the link.