By Ruth Black

Starting out

In my practice as a textile artist, I work largely with wool – a fibre which has been used since the dawn of civilisation. It was almost certainly one of the earliest fibres to be used in the manufacture of cloth. Its continued use right through to modern times is testament to its usefulness.

My own development as an artist has been very much influenced by happenings and circumstance rather than a planned progression, and living in the Highlands of Scotland means that wool is the fibre that just happened to be available at times when I wanted to explore a different route.

My mother had taught me to sew at an early age – or as she described it, she allowed me to have needle, thread and scissors – and although I have no memory of it, I could sew before I could read. Adding decoration to fabric in the form of embroidery or the addition of braids seemed to just come naturally. I was 10 before my legs were long enough to reach the foot pedal of my mother’s sewing machine, but once I got going with that, there was no stopping me – machines were the way to go! After a year away from home at university with no access to a sewing machine, I spent all my summer holiday earnings on my own machine, and have never looked back.

Broadening my skills

I was given a small table-top loom by my father when I was 15 – just a happy result of him being in the right place at the right time when a colleague was doing some down-sizing. As this was decades before the advent of the internet, I made a trip to the local library to find a book on weaving and from that figured out what to do with the loom. A friend with a knitting machine gave me a cone of Shetland yarn to weave with and I was off…….

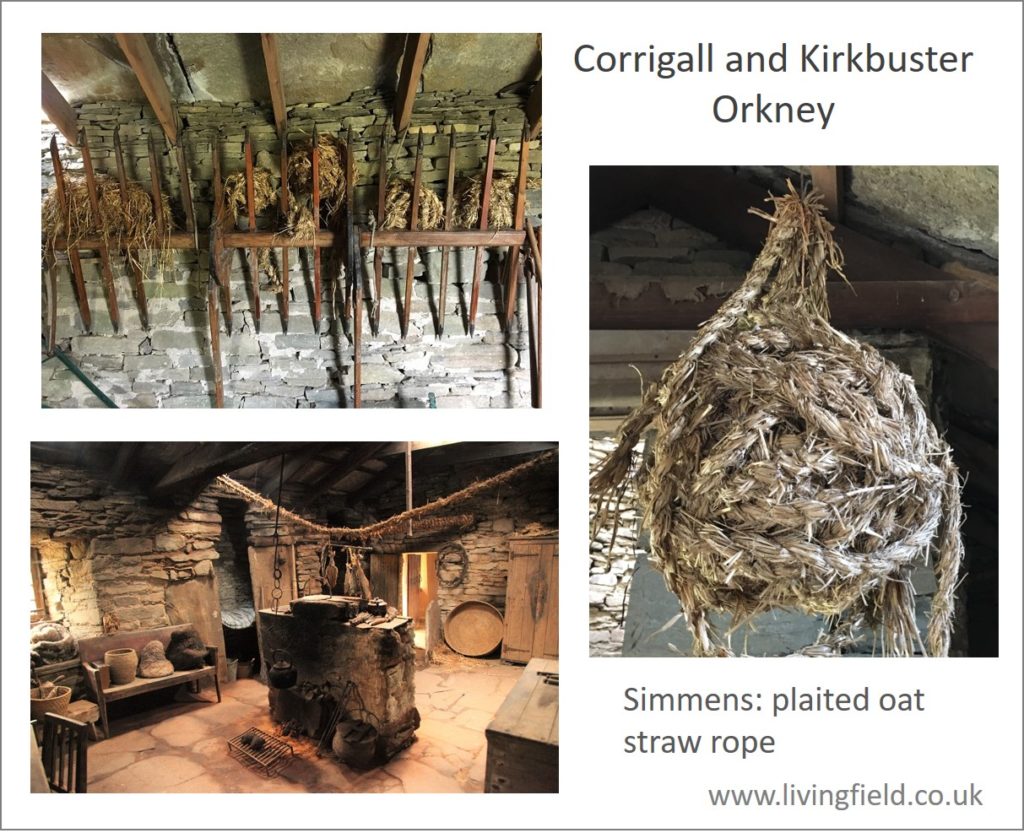

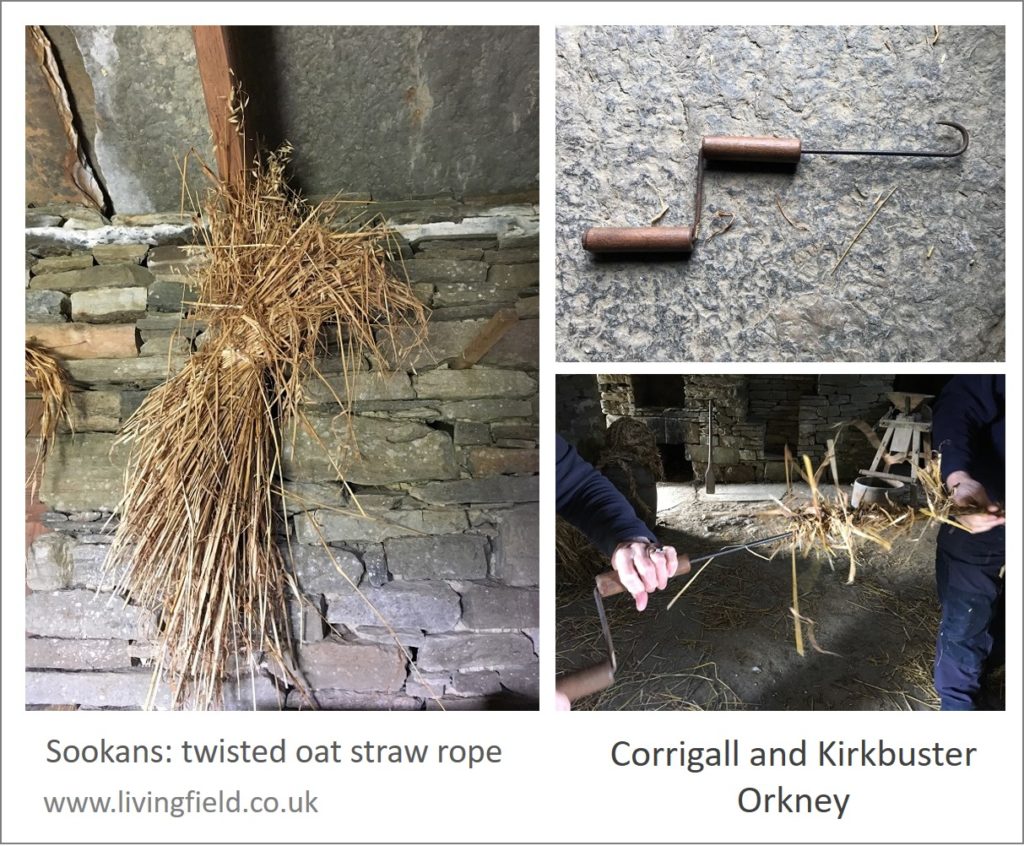

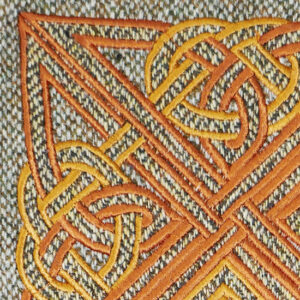

Over a couple of decades I was just a serious amateur sewer and weaver with occasional forays into machine knitting, hand spinning and various other textile techniques as and when time allowed, but in the early 90s I stumbled into the world of Pictish sculptured stones. As a design style, this really captured my imagination and figuring out ways to incorporate this art form in my embroidery resulted in me getting commissions for my work. And of course, the more I was asked to do, the more I was able to let my art develop and after a few years, I got to the stage where I was able to give up my day job as a school science technician.

Going professional

My mother had a small part-time business [1] making hats with Harris Tweed. (She started this because of taking early retirement and moving to the Isle of Lewis. The wind blows there, so warm hats were needed!) I helped her out whenever she was busy with orders, so Harris Tweed was always around and available for me to experiment with. The combination of Harris Tweed and Pictish design works really well and I discovered there was a market for my style.

Once I started working professionally I found I was able to invest in equipment that not only saved me time, but allowed me to develop my style in ways that had not previously been possible.

Embroidery machine

It was 2001 when I bought my first embroidery machine – a tiny domestic model that was very limited in terms of scale, but opened my eyes to the possibilities of what could be achieved with a machine so I saved up, and a couple of years later bought an industrial machine. And a couple of years after that, I added a bigger one………. Studio space prevents me from going bigger still. Two machines running side by side is all I have room for.

Laser cutter

The technique I developed for all my Celtic/Pictish inspired work is appliqué. This involves cutting out shapes of fabric, placing it on the background fabric and stitching over the cut edges. At first, this was all done with a scalpel on a cutting board, but it was a slow process that put a strain on my wrist, so when I discovered about laser cutters………. yes, it might be the same cost as a new family car, but I did the sums and figured out that it could pay for itself within 5 years so a bank loan was worthwhile. Speed and comfort are not the only benefits. Wool is a mobile, flexible fabric. As the laser does not actually touch the fabric at any time there is no distortion in the cutting process. The laser works by burning along a very finely focussed line and gives a sealed edge as the fibres burn away. In the case of wool this gives a slightly tarry, charred edge but this is later concealed by the stitching that goes over it. The down side is that my studio can sometimes smell a bit like a charnel house, but the smell quickly dissipates.

Looms

Family circumstances meant I was spending a lot of time going to Lewis for a few days every month. As a change from my embroidery I decided that while on Lewis I should improve my weaving skills. I managed to acquire an old Hattersley loom (and a shedful of Harris yarn to go with it) and set it up in my mother’s garage. It took a while, but I did get to the stage where I was weaving Harris Tweed and getting it stamped with the official Orb certification mark. The image below right shows an Orb design embroidered on my own weaving.

Wool is a lovely yarn to weave with, and almost all the weaving I have done over the decades has been with wool. It is a “forgiving” fibre. It has a degree of natural elasticity that makes it easy to weave with, and also easy to disguise mistakes and breaks. When it first comes off the loom it is quite hard and rough, but at this stage, careful examination gives the weaver a chance to do any necessary darning and once the tweed is washed you can’t tell where the problem was.

When my mother died I no longer had an island base for my loom so moved it to my studio near Inverness. Of course the weaving that I do here cannot be called Harris Tweed because for that the entire process has to be carried out in the Outer Hebrides, but I found that not all my customers were bothered about what the tweed was called – they were more concerned that it had been woven by me.

This year I decided I had had enough of the hard pedalling that was involved in operating the Hattersley loom and so I sold it on and invested in a new hand loom (photographs below) that has a computer dobby (the mechanism that lifts and lowers the shafts to separate the warp threads). This new adventure is allowing me to be much more experimental in my approach to weaving, and to use a wider variety of yarns. The gentler technique will also allow me to weave with my own hand spun yarns, so watch this space….!

Computers

With the exception of my sewing machines, all my equipment needs a computer to run. I now find that I design straight onto the computer most of the time, though I often do quick sketches with pencil and paper just to work out which way I am going to take a bit of knotwork or key pattern work. Being able to do the simple processes of copy and paste, flip and rotate allows me to easily bring the precision to my work that is so important in Pictish art.

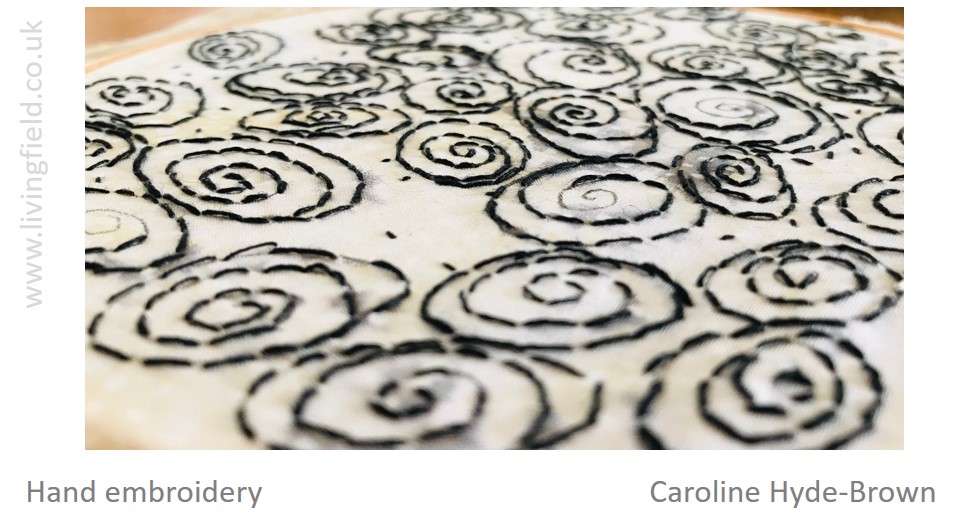

Low-tech techniques

Computerised technology has its place, and certainly makes it possible for me to create my art and sell it for prices that people can afford, but I do still use a lot of purely hand techniques. I weave braids and bands using a variety of methods – inkle weaving, tablet weaving and mini peg-loom. I often embellish little details of my machine embroidery with some hand stitching, beading or couching. I do a bit of hand dyeing and fabric painting, and quite a lot of hand spinning – mostly wool.

Felt making

In addition to working with woven fabrics – mostly wool and silk – I also make my own hand made felt. This is another ancient fabric making technique but it has only been in the last few decades that it has become a popular activity in Scotland. Unlike weaving and knitting, no yarn is needed – just loose wool fibres. It is basically a question of rubbing the wool fibres with soapy, warm water until they bind together – though of course things such as initial fibre preparation, the techniques used and the skill of the feltmaker all play their part in how the final product looks and handles.

An important feature of felt compared with woven and knitted fabrics is that it can’t be undone – once the fibres are felted, they can’t be separated. The advantage for my way of working in embroidery

is that felt doesn’t fray so there is less need for full coverage of the cut edges in appliqué work. I also make use of the thickness of the felt to achieve a semi-relief look in some of my embroideries. Although the felt has to be made largely with wool, other fibres such as silk and bamboo can be added sparingly to give interesting surface textures.

Creating my own cloths, whether this is on the loom, the knitting machine or at my felting table, means that I can blend colours in a way that would be impossible with shop-bought fabrics. As I am creating the fabrics I am thinking about how I am going to use them. If I am making clothing I will weave, knit or felt just the amount I need to make a particular garment and will introduce colour changes as I go along. If I am planning a piece of wall art it may be that I let the fabric develop organically and then decide how I am going to embellish it once I have the fabric completed.

I don’t really sample. With weaving I might weave a small section in 2 or 3 different colours of weft before I start for real, but generally I rely on my decades of experience and am confident that something will turn out the way I had envisaged – and if not, there are always other ways I can use a piece of cloth. Nothing is wasted. And while it may take a while to sell a particular piece, there is always someone out there who likes it enough to buy it. I am also very lazy about record keeping, so don’t ask me to repeat something. I can do something similar, but it won’t be the same.

Inspiration

In terms of what inspires me…. just about everything! I am always seeing things and thinking, “That’s a nice shape, colour or texture, how can I work that into my art?” I suspect I will never grow tired of Pictish design. Sometimes I take the ancient designs and recreate them in my embroidery – other times I just take ideas from them but develop my own designs. The possibilities are endless and as even now, ancient sculptured stones are still being discovered, I don’t anticipate running short of inspiration – just the time to bring all my creative ideas into being.

The Future for Scottish Wool and Textile Art

Scottish wool has had its share of ups & downs. Currently sheep farmers are getting a lot less for their fleeces than it costs them to shear the sheep. But it is not that there isn’t a market for the wool. Now more than ever, people want to use natural fibres but the systems and manufacturing capabilities are not in place to connect producers and customers. The Harris Tweed industry relies on local wool. The Outer Hebrides wool clip is not enough to support the current level of tweed production, so wool is brought in from mainland Scotland. Most British wool gets used in carpet manufacture because it is considered too course and rough to wear – but these features make it excellent for walking on. It would also be ideal as house insulation (wool is naturally fire retardant!) and we are all being advised to better insulate our homes. We need a bit of joined up thinking.

At the other end of the scale, some small scale farmers are making direct connection with textile enthusiasts who are happy to pay for nice fleece – particularly for some of the more interesting breeds.

I am currently working on a long-term project that is entirely for my own amusement rather than with thought of finding a paying customer. I am spinning my way through a couple of kilos of North Ronaldsay fleece. Once it’s all spun and applied I will venture into the world of natural dyes and then start weaving.

My ultimate aim is to use a combination of tablet weaving and loom weaving to construct my version of the Orkney Hood. However, I want a finished garment that is soft and luxurious, not something that looks as though it has been in a peat bog for 1500 years! This project has been made possible by the covid pandemic. As the world went into suspended animation, I found myself more in control of my time. It is quite liberating to work without having to be concerned about the commercial aspect of what I am doing, but maybe as I work I will try to figure out if there is a viable way to make such garments for sale – and see if there is a demand for it.

Author | links

Ruth Black

www.ruth-black.co.uk

The Workshop, Inchmore, Inverness, IV5 7PX

01463 831567 // 0777 177 4172

ruth@ruth-black.co.uk

[1] For my Harris Tweed products I trade under the name of my mother’s business – Anna Macneil www.annamacneil.scot

All images on this page by Ruth Black.

Ed: many thanks to Ruth for giving the Living Field such insights to her art and craft based on natural fibres and providing the photographic material for this article.

Postscript

And here is a photograph of some North Ronaldsay sheep from the Living Field’s collection (added 7 February 2022)