Australia. Wild plants. Indigenous knowledge. The Living Pavilion at Melbourne University 2019. The book ‘Plants – past present and future’. Plant blindness – our loss.

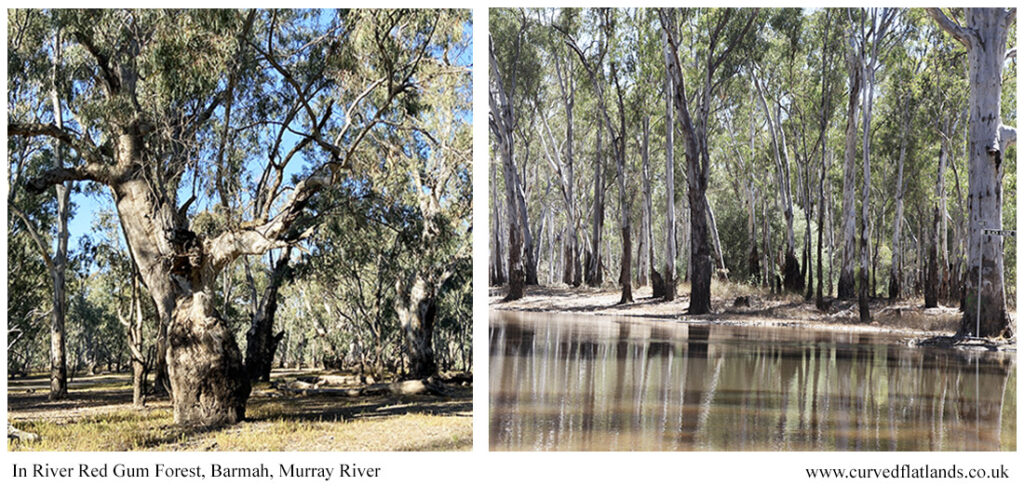

Recent travels [1] to see again the River Red Gums, Boxes and Ironbarks and all the other plants around the Murray River in Australia, led first to the Botanic Garden in Sydney [2] where among hundreds of species grew the grass tree Xanthorrhoea, famous for its gum but having many other uses, and the hairpin banksia Banksia spinulosa in full flower.

This Banksia, native to eastern coasts, was given its Latin name after botanist Josef Banks, who travelled with James Cook in the late 1760s, but the continent’s many Banksia’s – like many other Australian plants – had been known, named and used for tens of thousands of years before then.

Which thoughts were present on seeing a series of books on Indigenous knowledge [3] at the Garden’s shop. And reading one named Plants – past, present and future [4] was a revelation.

Plants by Cumpston, Fletcher and Head (2022) introduces many of the species that have sustained people in Australia, and makes the case for returning to these well-adapted forms as climate, habitat loss and soil degradation expose the limitations of some current agricultural practices. That’s for another article ….. but finding more about Plants led to the web presence and reports on Melbourne University’s Living Pavilion.

Living Pavilion 2019

The Living Pavilion [5] was an exhibition and centre of learning built in 2019 as a space, primarily occupied of plants, in which people could walk, see, touch, smell and wonder. It was part of CLIMARTE’s ‘ART+CLIMATE=CHANGE’ festival, 1-17 May 2019 [6]. Here’s an extract from page 9 of the the Living Pavilion report [5]:

“The landscape design transformed a seemingly unspectacular part of the campus into a haven of biodiversity and Indigenous stories through the installation of over 40,000 Kulin Nation plants, artworks, gathering spaces and soundscapes. It brought together Indigenous knowledge systems, community arts, performance, music, sustainable design and ecological science to showcase how transdisciplinary initiatives can sow the seeds of community vitalisation and environmental stewardship.”

The plants were the central feature of the Pavilion, assembled in a way that people could walk and sit among them, see, touch and smell them. Descriptive signage explained how Indigenous communities cultured plants in agriculture and aquaculture and derived many useful products from them [7]. A range of edible and medicinal plants, grown in an Indigenous Community Garden, taught the value of plants not only to people but to the wider ecosystem, including insects and other invertebrates.

For amphibian lovers, there was the Frog Fest including the Frog Soundscape which produced calls from a range of frog species in a re-creation of a waterway – the Bouverie Creek – which the university built over but which continues to flow beneath it. And there was more at the Frog Fest in the way of activities for children, like dressing as frogs, face painting and making frog life-stages in clay.

Art, craft, song and dance

Art and music was inseparable from the plants and their uses. Spaces were allocated to craftwork, singing, dance, art installations, demonstrations and soundscapes.

Artists and craftworkers taught the utility of native plants using traditional techniques. Stephanie Beaupark showed how fibres and dyes from native plants are used in weaving; while Katie West recreated a fishing net using materials and methods that few now know about [8].

Song and dance enlivened the festival, including performances from the Djirri Djirri Dance Group, The Orbweavers and The Merindas. You can get a feel for what it must have been like by visiting the performers’ web sites [8].

What resonates with the Living here is the belief that human society and culture are “an inherent and inseparable part of ecosystems”. The Living Pavilion’s logo, which can be seen on the web page is described: “The circle in the middle represents a meeting space. The water represents the creek that once flowed through the space and signifies journey and life. The plants represent flora and fauna and connection to Country and place.”

The Living Pavilion was the seventh in a series of events under the collective name The Living Stage developed during a PhD at Melbourne University by Tanja Beer. This bringing-together of people and culture with ecosystems and artistic performance continues through the project Ecoscenography – adventures in a new paradigm for performance making [9].

First knowledges book series

The book referred to above, Plants – Past, Present and Future by Zena Cumpston, Michael-Shawn Fletcher and Lesley Head, is one in a series titled First Knowledges edited by Margo Neale [3].

Another in the series is on land use and management, titled Future Fire, Future Farming by Bill Gammage and Bruce Pascoe. Here’s an extract from the publisher’s web: (the authors) ‘demonstrate how Aboriginal people cultivated the land through manipulation of water flows, vegetation and firestick practice. Not solely hunters and gatherers, the First Australians also farmed and stored food.’

An important theme in these books is that agriculture began tens of thousands of years before modern wheat, rice, maize and the other main cereals were domesticated from wild grasses. Similarly, systematic methods of land management were in place, for example to reduce the ‘killer fires’ that have caused so much destruction in recent years.

Lessons for the Atlantic zone croplands

There is much for us to learn from these books. Little is known of plants and land use in northern Britain and Ireland before to the retreat of the last ice 10,000-12,000 years ago. Modern crops have been grown here for only half that time, but before their arrival, and until recent centuries, people used wild plants for food, medicine, dyes, clothing and building.

Knowledge has been retained in written records, including accounts originating during the monastic expansion from Europe [10] and in more recent herbals [11].

Yet while some specialists are re-learning and extending plant knowledge today, the broader existence and utility of plants is unknown to most people [12]. It’s not just the knowledge that is fading – the plants themselves have also been made rare or extinguished. The recent Plant Atlas 2020 by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland [13] shows loss and extinction are continuing.

One of the main aims of the Living Field has been to show people the wealth of plant life in our region, especially the older crop species and varieties that are no longer grown and the many native plants and long-term introductions that have been used in various ways since the retreat of the ice. We will continue with that work.

The Living Field here could also learn from the Living Pavilion in Melbourne. We could bring in far more plant species and varieties for people to learn about. We could restore forgotten uses of our native and introduced species and link them to our cultures and places. And perhaps more than anything, we can feel we are not alone in the restoration of our botanical diversity – people throughout the world are doing the same.

There are organisations in the UK to help if you want to know more about plants and get involved in their conservation [14]

Sources | links

[1] The editor writes of a visit in March 2023 to Australia.

[2] Royal Botanic Garden Sydney: https://www.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/

[3] First Knowledges series edited by Margo Neal. For details on all books in the series: Thames and Hudson Australia web site.

[4] Cumpston Z, Fletcher, M-S, Head L. (2022) Plants – past, present and future. Thames and Hudson Australia, 212 pages.

[5] Living Pavilion at the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub where a substantial report on the project can be downloaded (cover shown above). Citation: Beer, T., Hernandez-Santin, C., Cumpston, Z., Khan, R., Mata, L., Parris, K., Renowden, C., Iampolski, R., Hes, D. and Vogel, B. (2019). The Living Pavilion Research Report. The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

[6] CLIMARTE an Australian charity founded 2010 ’harnesses the creative power of the arts to inform, engage, and inspire action on the climate crisis’. Web site: https://climarte.org/ The group’s ART+CLIMATE=CHANGE 2019 Festival ‘presented 33 socially engaged exhibitions and events … across Melbourne and regional Victoria’. The Living Pavilion was one of them. Festival web site: climarte.org/project/artclimatechange-2019 where there are links to the full programme, podcasts and other resources.

[7] Cumpston, Z. (2020). Indigenous plant use: A booklet on the medicinal, nutritional and technological use of indigenous plants. Downloadable at Living Pavilion web page at Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub [cover shown right, see also 5].

[8] Performing at the Living Pavilion 2019 – some current web links : artists in residence Stephanie Beaupark and Katie West || Singing and dancing from Djirri Djirri – Wurundjeri Women’s Dance group || The Orbweavers – their song Reeds Rush links several features of the Living Pavilion || and The Merindas.

[9] Ecoscenography by Tanja Beer: blog, reading group, articles and artworks, ecological design for performance.

[10] Living Field articles on the uses of medicinal plants and the transmission of plant lore at religious sites: Medicinals through the Ages 1; Medicinal Forage – Kinloss Abbey; Labours of the Months – the Easby Murals

[11] Modern herbals and books and plant lore are listed at the end of the Living Field’s Garden/Medicinals page.

[12] Plant Blindness – a human inability to see plants, differentiate between them, understand what they do, accept them as the basis of animal and human life. More at Wikipedia including pointers to research and teaching material e.g., Wandersee, J. H., & Schussler, E. E. (1999). Preventing plant blindness. The American Biology Teacher, 61, 82–86.

[13] The recently published Plant Atlas 2020 by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland details the serious declines in native plants and plants introduced in the distant past, contrasting with the spread of recent introductions. See the Living Field’s notes on the latest and previous atlases at BSBI Plant Atlas 2020.

[14] Want to get involved with plants? In the UK, find out more through the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland and Plantlife – both organisations promote plants through learning, training, meetings and visits, and welcome plant enthusiasts from absolute beginners to experts.