Oilseed rape, swede, turnip and cabbage. The complex of volunteers, ferals, crops and wild relatives. Its role in transmitting and holding genes. Impurity in crops.

The plants of the Brassica complex are among the most useful. They give us cabbage and cauliflower, calabrese and broccoli, swedes (neeps) and turnips, cold pressed rapeseed oil.

They are also central to much of the debate, and the acrimony, of recent years, on the transmission of GM impurity in the human food supply chain. Several plant species are involved, of which three are the most important – oilseed rape Brassica napus, turnip Brassica rapa and cabbage Brassica oleracea.

- history and background

- role of oilseed rape Brassica napus

- the cabbage Brassica oleracea

- the turnip Brassica rapa

- other species

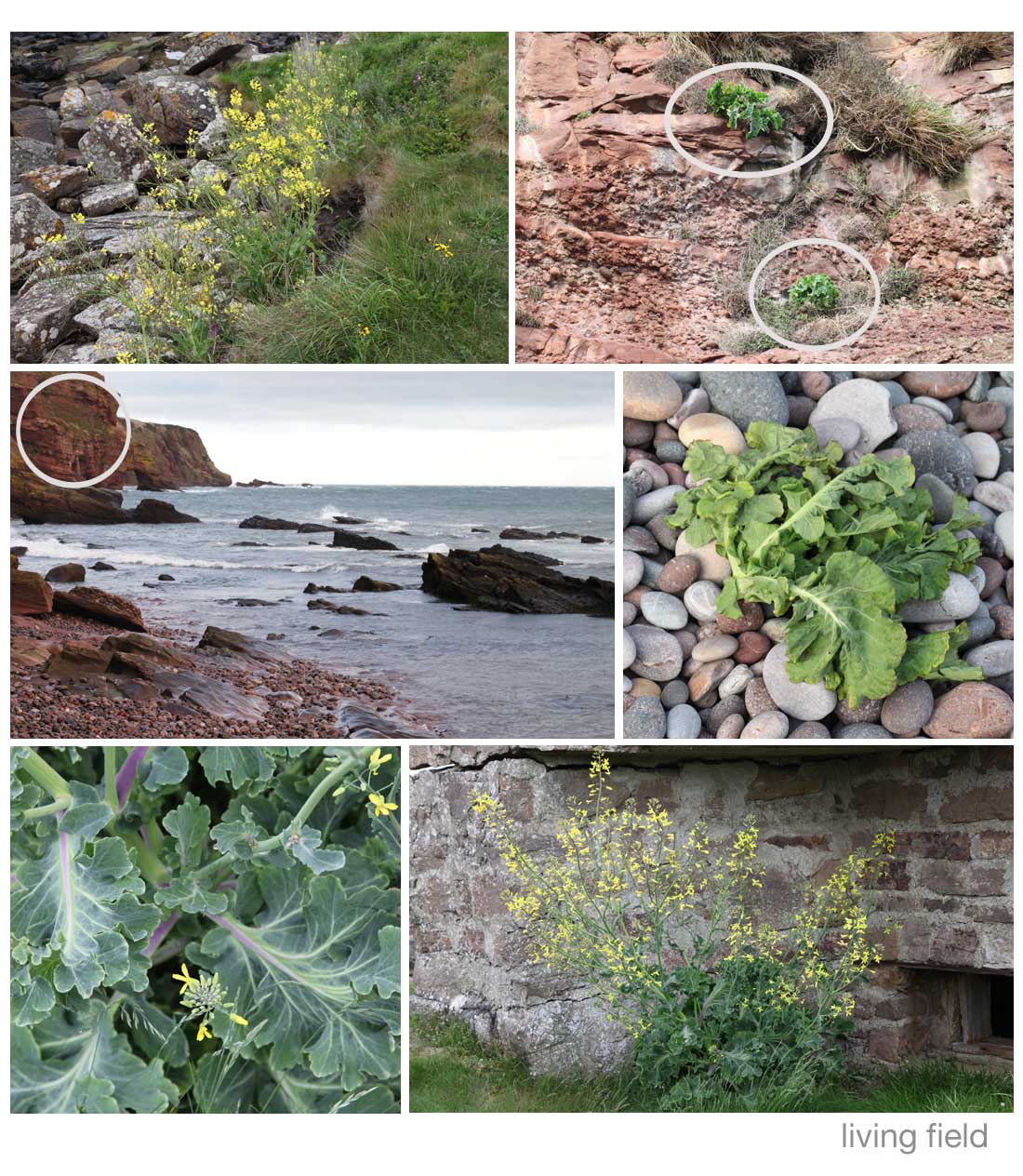

Images above show the habitat and plant of wild cabbage Brassica oleracea: centre left, cliffs of the east Angus coast near Auchmithie, location of plants shown by the circle; top right, individual plants circled on the cliff-face; centre right, clump of leaf, broken off and fallen to the stony beach below; top left, large flowering plants near the bottom of a rock slide; lower right, large flowering individual by an old sea-defence structure, near Crail, Fife; bottom left, glaucous (bluish) and purple foliage of the plant (all images Living Field collection).

Note on naming: ‘rapeseed’ is used widely in Europe to mean the product (seed) of any of the oilseed crop varieties of the complex (see Brassica napus and Brassica rapa below). ‘Oilseed rape’ has in recent years come to be used for the oilseed form of Brassica napus and that use will be retained here.

History and background

It is often thought that the yellow-flowering rapeseed crops and their roadside ferals are a modern phenomenon, but they are not. Rapeseed has been grown for many centuries in Britain. It’s just that it was not grown much in the 19-hundreds before the 1970s, so there are hardly any old photographs of it and people assume it did not exist before it ‘suddenly appeared’ about 1975.

So for historical authenticity – yellow rapeseed fields should not be seen in colour movies set in the UK in the middle nineteen-hundreds, but may be excused in medieval costume dramas.

The crop species occur in different forms as a result of selection and breeding. Both B. napus and B. rapa have root and oilseed forms. For example, the yellowish-orange mash known as neeps in Scotland (swede some other places), is the same species as the yellow flowering oilseed rape – both are B. napus.

The oilseed forms (mainly napus but some rapa) have been mostly beneficial to modern cropping in northern Europe. They provide a ‘break’ between cereal crops, to allow control of weeds and disease. They usually support a diverse weed flora and invertebrate food web and yield a wide range of products for food and industrial usage.

As a vegetable oil, rapeseed supplanted animal oils in some industrial applications. The Signal Tower Museum in Arbroath, describing conditions at the Stevensons’ Bell Rock lighthouse, related that sperm whale oil was replaced as the energy source for the light in the late eighteen-hundreds by colza (a French name for rapeseed, implying it was imported rather than grown locally). The colza was itself was later replaced by coal-derived oils.

Modern relevance and importance

So why is the Brassica complex of particular interest today? It is not only that it gives us a wide range of nutritious and tasty food. The reason for the scientific interest is to do with the transmission of genetic material between parts of the complex. Some of the species cross-pollinate with each other. All leave volunteers and ferals, some of which have become important weeds. Some have wild relatives.

The interactions, including the transmission of genetic material, between members of the complex offer opportunities to study gene movement, local adaptation, selection and evolution.

When GM oilseed rape was proposed for trialling in the UK, government initiated studies on the potential for the movement of the GM trait among B. napus and B. rapa. (There is no cross pollination with the cabbages, B. oleracea.) The studies taught us much about the way crops, weeds and other wild plants both depend on and interfere with each other.

Here is a brief account of the three species and their various forms.

Oilseed rape Brassica napus

This is presently the most widely grown crop in the complex. Most of the bright yellow fields seen in spring and early summer are of this species. The seeds are crushed for edible oil and animal feed and also certain varieties – commonly known as double high (high in glucosinolates and high in erucic acid) – are used to make light industrial oils.

- Oilseed crop – common and widespread in northern Europe where it is generally called oilseed rape; either sown in autumn and flowering early spring, or sown spring and flowering a few months later.

- Root crop – neeps (as in haggis, neeps and tatties) is the same species, bred over generations to enhance the tuber. It is called swede or swedish turnip in some parts of the world. Its flesh is yellow-orange, distinct from the white of the turnip. Since oilseed rape and neeps are one species they cross pollinate if they flower at the same time. (Cultivated neeps are usually harvested well before they flower.)

- Volunteers – by far the commonest in-field weed of the Brassica complex is derived from B. napus oilseed crops; it is now among the ten most abundant weeds in Britain.

- Ferals – similarly, by far the commonest yellow-flowering feral seen along roadsides and in waste ground is derived from the oilseed version of B. napus.

- Wild relatives – none of the same species.

- Cross-pollination – all B. napus types can cross pollinate with each other and with forms of B. rapa but not normally with B. oleracea. Their genes are carried over many kilometers by wind and insects. They form an interacting, shifting network in the landscape.

So where did Brassica napus come from? The cabbage B. oleracea and the turnip B. rapa are its ‘parents’ but how they came to produce this prolific offspring is unclear. It is difficult to get them to repeat it, even in the laboratory.

The cabbage Brassica oleracea

The cabbage is one of the most useful plant species. What would we do without its vegetative variants such as sprouts, broccoli and calabrese! Its wild nature is biennial or perennial, but some cultivated forms flower in one year.

- Oilseed crop – if allowed to flower and fruit, the seeds have oil in them, which has been used in medicinal preparations, but cabbages are rarely grown as oilseed crops today.

- Root crop – not as these either

- Volunteers – cabbages occasionally leave volunteers if the plants are left to seed; their flowers are a paler yellow than those of oilseed rape, but are rarely noted or identified.

- Ferals – as for volunteers.

- Wild relatives – the wild form of cabbage (same species, B. oleracea) grows by the sea in certain places, mostly on the tops and faces of steep cliffs. There are some in Scotland – where individuals seem to persist for years precariously hanging or more luxuriant near the bottom of unstable slopes. Plants reared from seed taken from a Scottish location in 1998 survived at the Institute until 2014.

- Cross pollination – since it does not normally hybridise with B. napus or B. rapa, its day to day contribution to the spread of genes and impurity in the complex is virtually zero.

The turnip Brassica rapa

The turnip certainly makes the rapeseed complex more interesting by its two forms (oilseed and root, just like napus) and its similar appearance to napus. Up close, it is brighter green and hairier than the glaucous or bluish-grey napus or the cabbage. The oilseed form was grown in the north of Britain, but has been largely replaced by new varieties of napus.

- Oilseed crop – grown in Scotland as recently as the 1990s, but rare now.

- Root crop – having mostly white flesh and commonly called the turnip, is widely grown for human and animal fodder.

- Volunteers – still around in fields in east Scotland, but the age and exact origin of these populations are uncertain.

- Ferals – as for volunteers, found occasionally.

- Wild relatives – a wild relative of the turnip (same species) lives in some parts of Europe, for example along river banks in England, but not to our knowledge in Scotland. In some northern European countries such as Denmark, it occurs commonly in and around fields.

- Cross pollination – a pecularity of the complex is that the cultivated and wild forms of the turnip will cross pollinate and hybridise with B. napus. It was previously thought the hybrids were weak and left few offspring, but recent findings in Denmark show that some of the hybrids are as fit as the parents. Wild, volunteer and feral B. rapa therefore provide additional means for the movement and transmission of genes from oilseed B. napus.

Other species

The wild radish Raphanus raphanistrum, the wild and cultivated mustards e.g. Sinapis alba, charlock Sinapis arvensis and several similar species occur in farmland, often in similar places to volunteer and feral oilseed rape, but with the possible exception of the wild radish are not involved in the movement of genes in the rapeseed complex.

Some of these species have entered fields as unwanted impurities in rapeseed crops, or sown covers for game or wildlife, so it is very difficult to tell the time of their introduction or origin.

A cabbage field of uncommon interest

It is rare for the three species, oilseed rape B. napus, turnip B. rapa and cabbage B. oleracea to cohabit the same piece of land, but this occurred in certain fields near Dundee about 15 years ago (around 2000). The fields had previously grown turnip oilseeds in the early 1990s that left volunteers in the soil seedbank, and in some later years B. napus oilseeds, that also left volunteers. Both types of volunteer lived comfortably together with other weeds in the soil seedbank, occasionally emerging and perhaps re-seeding. The volunteers were not much seen in cereal crops, but in the year in question, the field was contracted out to cabbage growers.

Now it is almost impossible to control these volunteers by herbicides in cabbage, and so all three – the planted cabbage and volunteers of the two oilseed forms grew together. In some places, you couldn’t see the cabbage for the volunteers.

The cabbage did not cross-pollinate with the others or in any way alter their genetics – it simply provided the opportunity for them to flourish. Both volunteer forms seeded before the cabbage was ready to harvest and replenished their seedbanks in abundance. Their seed and offspring, which probably includes hybrids between them, will remain in the field for many years to come.

In the ecology of arable systems, rare coincidences like this may start traces that lead for many years. Which brings us to five years ago, 2010, when the field was contracted to cabbage growers and again, the two species of volunteer were growing and flowering side by side in the same field.

Images above show the field in 2003: top left, the broccoli plants left to flower (note the same pale yellow as the wild cabbage above); bottom right, earlier, the broccoli showing dark blue-green, the weed shepherd’s purse Capsella bursa-pastoris maturing down the centre and to the right, and a row of taller oilseed rape to the left; top right, single oilseed rape volunteer maturing and bottom left, stump of cut broccoli and oilseed rape or turnip rape seeded branches on the soil (Squire/Living Field, 35 mm slide scans).

The future

Plants of the Brassica complex should continue to offer a range of oils, tubers and forages for the benefit of people and their stock animals. In general, they are good for farmland wildlife, not least in tolerating the declining broadleaf weed flora.

The question is whether volunteer weeds and ferals have a future independently of the crops. It is rare for ‘new’ weeds to enter the arable flora. The oilseed napus and rapa have a chance because their seeds can survive as long as those of many other arable weeds.

Questions around GM crops have raised interest in volunteerism and ferality. Crop-weeds will have been a part of the agricultural scene since the first domestications. They will continue to be part of that scene whether or not GM crops are grown.