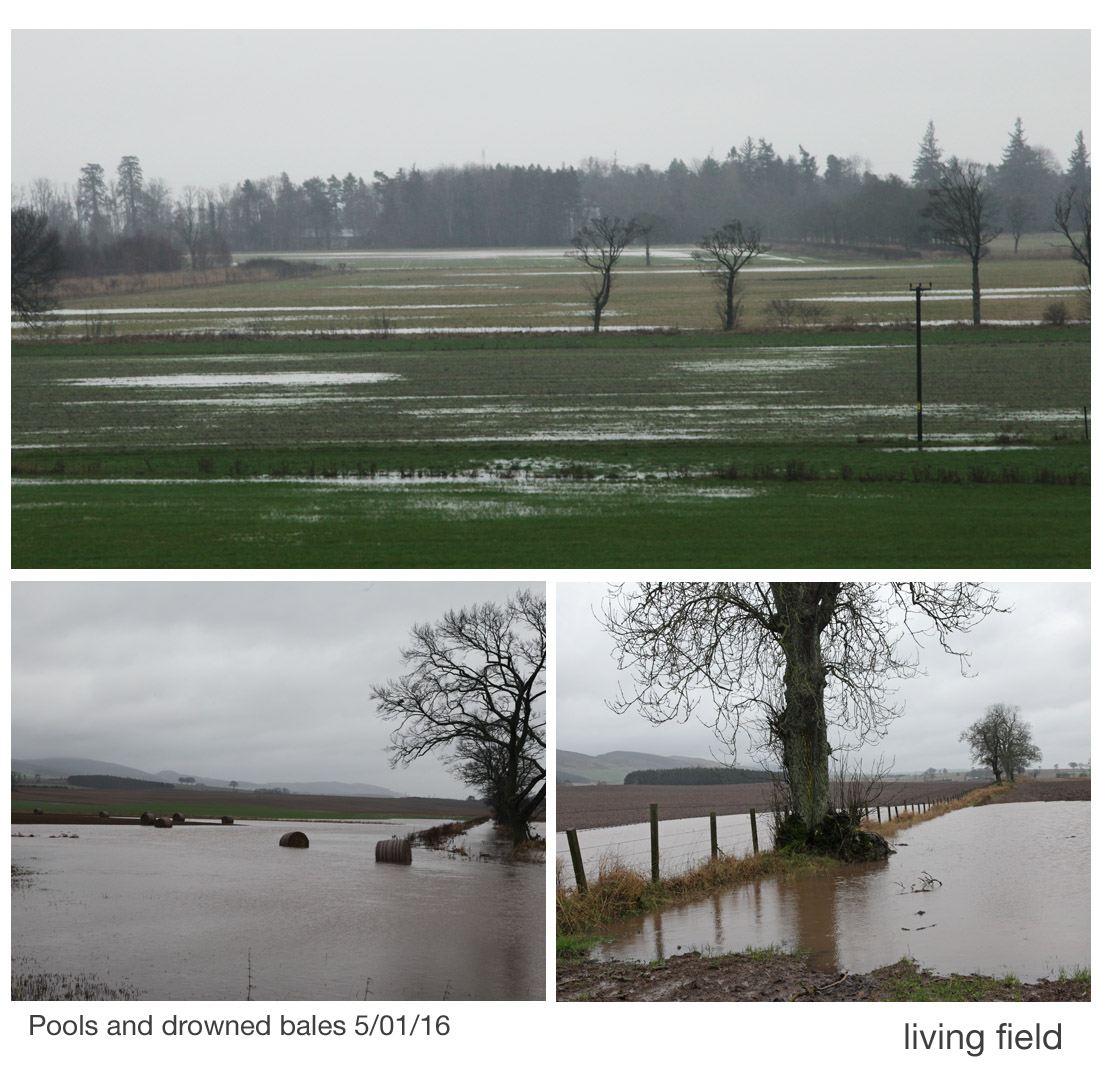

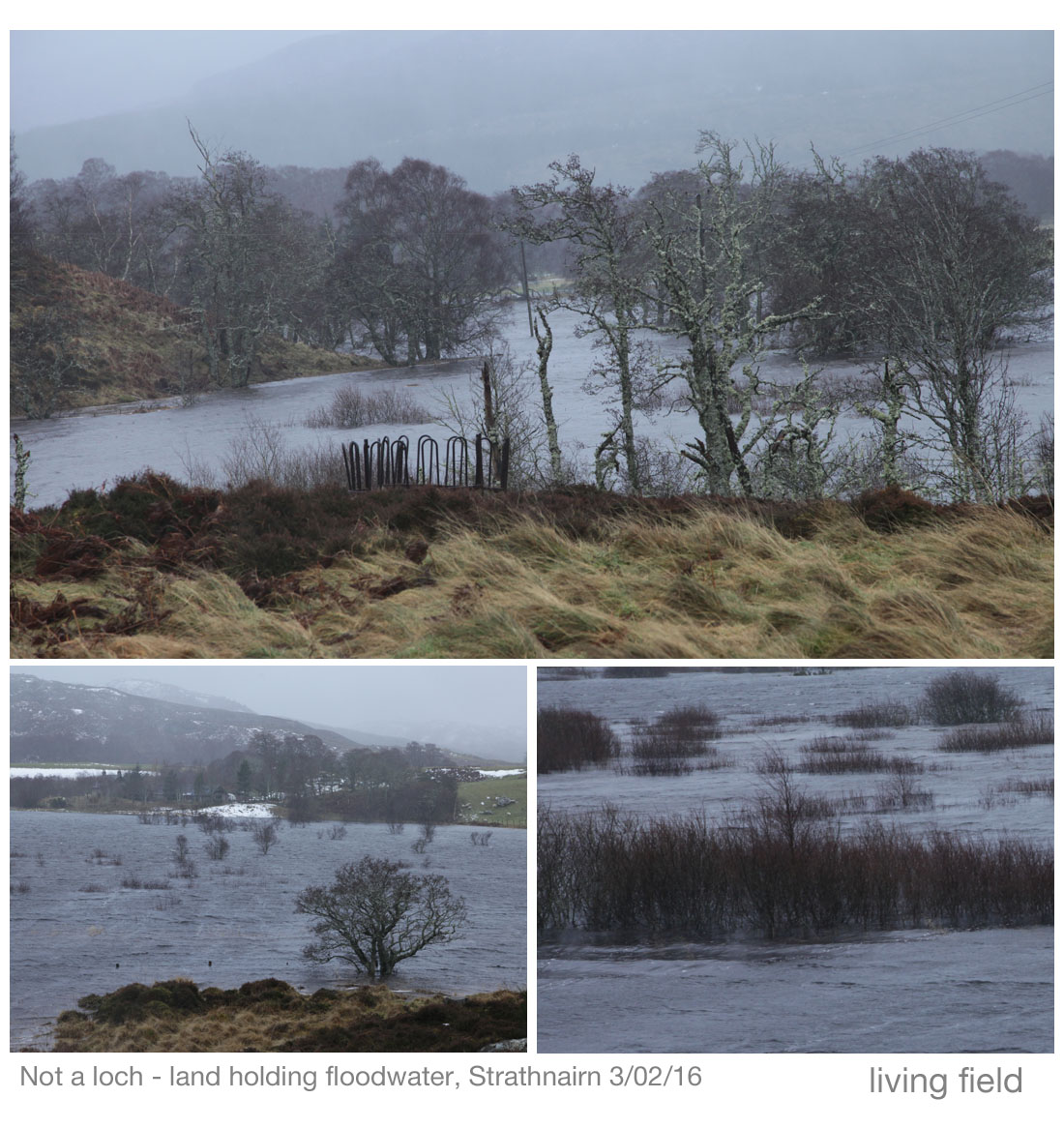

The winter floods of 2015/16. The effects of flooding and saturation on fields. Erosion and pollution. Loss of crop. Dense cloud, low solar income. Blame. Restoration and remedies. Link to page on the autumn 2012 flooding.

The high rainfall in the early winter months of 2015-2016 filled the soil. Most level fields showed patches of standing water, but it was the heavy falls of late December and early January that caused the problems. The water could not drain through the soil. It ran off the land straight into drainage channels and down to the rivers. The flow was too much for the rivers and water washed over their banks and across the floodplains.

The immediate attention was to the damage caused to people and property. The longer term effects on fields and crop production are not yet known. Three years ago, the wet autumn of 2012 took as much as a third off the high-intensity crops at harvest. What will this winter’s floods do?

Excess water has several different effects depending on whether it washes over fields, submerges them completely or just lies in patches. Here, we describe the way excess rainfall and flood might harm or benefit fields.

What happens when water washes over fields?

In many places it was possible to see water rushing over fields or along the ‘tramlines’ left by tractors or as rivulets finding the easiest way out. Moving water takes with it soil particles, remains of plants and dissolved materials such as fertiliser and other agrochemicals.

If the water flows into another field, it might deposit some of this material on to soil and crops. If it flows on to a road, then it deposits it on the road. ‘Mud on road’ signs are now a regular sight in the croplands. If it flows into a waterway, then the water plants get covered in soil. If the flow is strong, it takes the materials to the lower, slower reaches and silts them up, or takes the soil and all the nutrient it contains out to the sea. It won’t come back.

Previous studies in the region indicate that fields lose more than they gain. Careless agriculture speeds up the geological process of erosion. Rivers that are normally clear turn brown when flowing through eroding farmland.

What happens when water submerges fields?

If the water is standing still or moving slowly, the particles of soil and plant matter held in the water sink to the bottom, taking carbon and any nutrients with them.

The soil might smother plants growing in the field, but it can also add to the field. This is how floodland agriculture works over the world: plants grow on nutrients brought from upstream.

If the water stays for a long time, several weeks, it will, in effect, ‘drown’ the plants below. They will be deprived of air and when that happens, various chemical reactions may take place that produce toxic substances. Being submerged for weeks on end can destroy crops such as potato and winter cereals.

When water saturates fields and lies in patches?

In most places fields are not so much flooded due to water running into them, as saturated from rain falling on them. For most of the year, rain falling on soil infiltrates and fills pores that have been formed previously through the actions of small organisms such as worms and microbes. Water then drains through the soil under gravity; but if rain keeps falling on a soil that’s already full, it can’t get in, so accumulates in patches on the surface.

Eventually the water in the patches drains through the soil, but in recent weeks the rate of rainfall has been greater than the rate of drainage, so most soils, even on slopes, have had water showing on the surface.

Soils that are saturated for a long time suffer the same ills as submerged soils. Young crops can be drowned. The soil loses some of its structure – it slakes due to the pressures of being waterlogged. Slaking causes the soil to have less cohesion, to be more easily eroded. Also as the water drains through the soil to bedrock and on the streams and rivers, it takes carbon particles and nutrients with it.

So flooding is bad for soils …. ?

Mostly, in this country, yes. The exceptions are those cropping systems that are managed as periodically flooded land. In some parts of Britain, water-meadows are designed and managed in this way.

It is not the same everywhere. In some countries, flood water is essential for growing crops. Many rice fields in the tropics are nourished by a controlled flood. Crops grown in the dry season by the banks of some tropical rivers survive on land that was under the river in the wet season. Intentional flooding, by diverting a water course during the ‘rains’, is also used in some dry lands to fill soil with water. The soil might get little more water for the rest of the year – but the crops grow on this stored water.

In our croplands, too much water, whether from overflowing rivers or from excess rainfall falling on fields, is mostly bad for yield. The system is not geared to so much water. Crops such as potato and winter wheat would not be grown on flooded soils if the growers knew in advance they would be flooded.

The main longer term effects of too much water is further erosion, loss of soil carbon, slaking and loss of soil structure. All these can be reduced or even prevented, but only if much more attention were given to designing land so that it retains water and growing vegetation that does not mind being waterlogged (see below).

And what about the cloudy skies?

The wet weather of late autumn and early winter of 2015/16 is unusual in lasting so long. The average daily solar income in a typical December is 5-10% of that at the peak in June and July. Prolonged dense cloud keeps it to, or even below, the lower end of that range.

The low light does not matter for spring-sown crops because last year’s have been harvested by September and next year’s will not be in until April, but it does reduce the growth of winter crops and grass. Winter oilseed rape and winter wheat, for example, rely on the winter light to grow some leaf and root, to enable them to withstand the killing effect of low temperature and to take advantage of the rising solar income in spring.

Prolonged low light with the additional set back due to being waterlogged or submerged may seriously affect the survival and growth of these winter crops. Years like this have few precedents. We will not know the effect of the wet weather in December and January until about March 2016.

Is anyone to blame – is drainage a problem?

Some have been quick to lay blame – on land-use higher up the catchment, on the compaction of soil caused by heavy machinery, on policies that discourage dredging of the lower reaches of rivers, on policies that allow building on floodplains; and so on.

And while some practices such as denuding uplands and draining cropland will have contributed, the causes and the solutions will not be the same between catchments.

Draining cropped agricultural land was necessary to raise yield. Temperate cereals and ‘root’ crops do not like to have their roots in water-saturated soil. The roots need air and the air diffuses down into soil through a network of pores. If the pores are full of water, the air cannot get in.

Early ploughs, whether pulled by animals or early tractors, turned over little more than 15-20 cm of soil. Over time, a hard ‘pan’ built up at this plough depth and reduced the downward percolation of water. Soils soon became waterlogged in autumn.

So to improve the yield of crops, farming cut in channels through the pan, filled them with porous material and sometimes laid ceramic drains at the bottom, so that water passed through the plough layer and out of the field. In flat, low-lying areas, bigger, deeper channels were cut round the outside of fields to take the water away.

The draining of fields was one of the main aids to agricultural improvement over the centuries, but it increases the immediate load on waterways down the catchment. One thing is sure – a country growing temperate crops can’t have both high yields and waterlogged fields.

Whatever is done to improve things, there will still be exceptional years like this one when there is simply so much water that soils become full – even with the best management the water held is limited by the depth of soil down to the bedrock. There is then nowhere for the rain to go, except off the surface of fields and into drains and waterways.

Restoration and remedy

The recent winter floods of 2015/16 are not the only ones in recent memory. The flooded soils of late autumn 2012 probably caused greater problems for farming, but the fact that yields could recover in 2013, and then take advantage of the high solar income in 2014 to produce near-record yields, shows the cropping system can still take a hit and recover. [See The late autumn floods of 2012.]

Even so, much soil and its carbon was lost in 2012 and a lot more will be lost in winter 2015/16. The croplands can’t take this year on year.

Researchers at the Hutton are examining how to reduce the loss of soil and chemicals. Interventions include sowing field margins to reduce the surface flow of water; adding carbon to soil from processed urban waste to increase infiltration and the soil’s capacity to hold water; roughing up the tramlines to reduce the run-off; using machines that ‘tie’ ridges in potato fields to allow water to accumulate in furrows rather than run off the field; and the use of undersowings and crop mixtures to reduce the time the soil is bare of vegetation.

Other options include constructing barriers of soil and perennial vegetation to obstruct the flow of water, and constructing ponds in lowland fields to hold back flood-water.

Solutions in conflict

Each catchment will need detailed study from which specific causes may be identified and remedies may emerge. If farming is to hold back water, as is proposed, then it will come at a cost to agricultural output. The skill will to get the greatest benefit for least cost.

Catchments will need to be managed as a whole. Most catchments already have areas in the middle altitudinal reaches that might be low in pasture quality but flood temporarily after heavy rain (see images above). Such areas could be lightly engineered to hold back more water, but society as a whole will have to pay for it.

Piecemeal approaches will not be enough. The pros and cons need to be costed and implemented through a plan for each catchment that considers rural and urban areas as a whole.

Sources, references

Images were taken (and impressions remembered) by Geoff Squire on various journeys around the wet croplands in October 2012 and winter 2015-2016. Memories of the monsoon!

Background information on yields is available in various government statistical publications. See Economic Report of Scottish Agriculture 2015 and previous volumes.

The innovative practices mentioned are being tried at the Centre for Sustainable Cropping, a Hutton field research platform near Dundee.

A general background on soils is provided in a technical publication edited by Dobbie, Bruneau &Towers, The State of Scotland’s Soil (2011).

[Met data …. in progress ….. ]