The Living Field project has been sharing knowledge of ancient and modern cereal grains for over 10 years [1]. Here we look back at how things evolved from field studies in barley on the Institute’s farms to growing our own range of cereals and finally using bere barley and other flours to make bannocks, bread and biscuits.

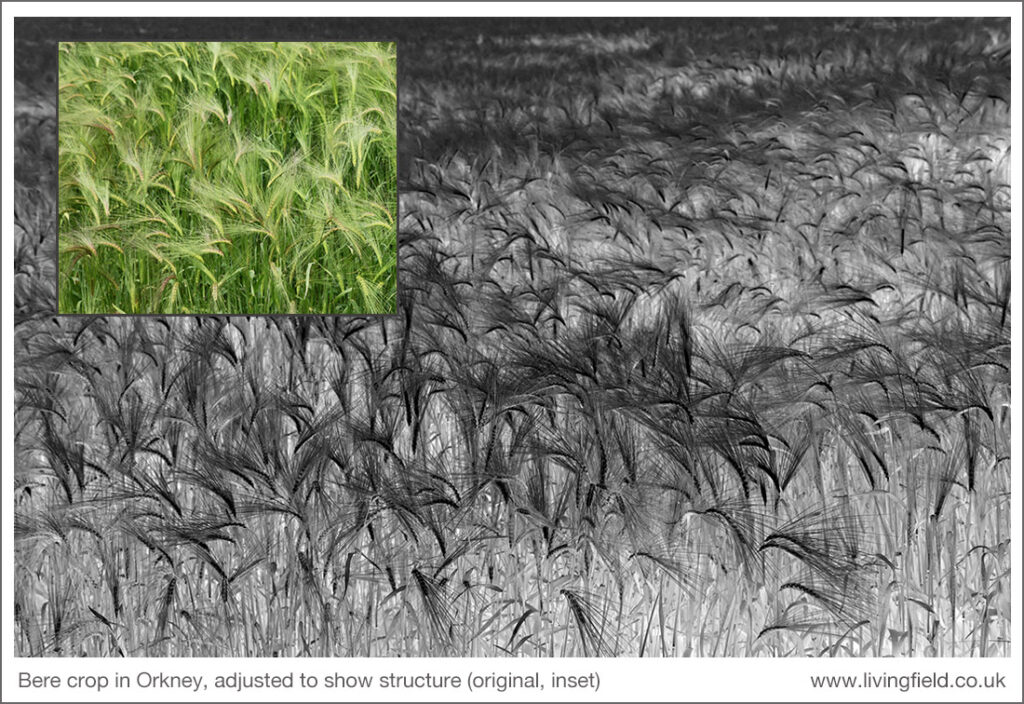

The sequence is shown here for bere barley. Seeds are sown, crops are grown. Bere plants support reproductive heads or ears holding grain. Plants are harvested and the grains removed and cleaned. They are ground into meal or flour, then used alone or mixed with other flours to make bread, bannocks and biscuits.

This sequence has sustained people for thousands of years. Today the grain we eat in Scotland, except for oats, is not grown here – the main cereal products from local fields are alcohol and animal feed. But whatever the future of agricultural produce, the grain-based cycle will remain essential to settled existence. In this retrospective, we describe the Living Field’s shared experience of ‘seed to plate’ over the last 10 years.

School visits to the farm’s barley fields

We began by introducing visitors to the James Hutton Institute’s fields where barley is grown both for experiments and for commercial grain sales. From 2007, the Living Field has been using the farm’s barley to give school parties a first taste of life in the crop.

The larger image above looks down from a barley field at Balruddery farm to the Tay estuary. The school children in the pictures were visiting fields of young barley at Mylnefield farm just above the Tay. This was in May 2007. They walked along the ‘tram lines’ looking at plants and finding ‘minibeasts’ – the first time many of them had been in a crop. They were fascinated with small creatures found crawling on the plants or walking over the soil [2].

The public interest in crops and their ecology in those early visits encouraged us to explore a much wider range of cereal plants than presently grown in commercial agriculture.

Ancient grains at the Living Field Garden

So began a small collection of grain crops which were sown, tended and harvested each year in the Living Field Garden [3]. We began in 2010 by growing bere barley from Orkney, black oat, emmer and spelt wheat, alongside modern varieties of barley, oats and bread wheat. Rye and a landrace of bread wheat from the western isles were added later, then several other barley landraces and old varieties [4].

The collection of photographs above shows (top right) a general view of the garden including a tall cereal plot in the middle of the photo, then c’wise from upper right – a barley landrace from Ireland, rye, black oat, emmer wheat, young spelt ear, spratt archer barley and a bread wheat landrace.

By 2011, the Living Field had combined its practical experience on the farm with the collection of ancient and modern grains in the Garden. Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson had perfected the way to grow all these different species. We now needed a means to demonstrate processing the grain and making food from it.

Milling and baking

The harvest from the small plots in the garden was too little to make flour enough for open days, road shows and exhibitions. Additional grain and flour (or meal) was begged or bought from a range of sources, notably Barony Mills in Orkney and ‘Quaker Oats’ in Fife.

The Living Field then bought its own rotary quern for grinding the grain into meal and chaff, which is the name given to the other bits we don’t usually eat, mostly the protective sheathing around the grain and the awns.

Now to make a loaf! Fortunately one of the team, Gillian Banks, was already an experienced bread-maker and after some experimentation turned out tasty loaves made from various mixtures including bere and modern barley, oats, emmer, spelt, wheat, rye …. and more [5]!

The whole chain from sowing seed in the ground to making food could now be demonstrated from first-hand experience. We did this at various open events beginning 2012.

The panel above shows (bottom left, clockwise) – visitors experiencing a range of ancient grains and flours, demonstrating the rotary quern, a sheaf of spelt, making things from sourdough, and a four-panel set showing oat grain in a bag, sieving and sorting meal from chaff and finally bread.

Open Farm Sundays

The highlights of our outreach over the years has been LEAF Open Farm Sunday. The Institute is a LEAF innovation Centre [6], so on the first Sunday in June, the farm and science come together to host the event. One of the main attractions is the hub of activity around the Living Field garden, cabins and tunnel. Typically 1000-2000 people visit the hub during the day. We’re mobbed ….. thanks to all!

The essential structure of a successful open day is, firstly, to provide plenty of things to do for young children, to keep them occupied and allow time for older children and grown-ups to talk about what’s on view; and, second, hands-on activity with natural products, things such as living plants, and grain and flour that can be touched, felt and smelled [6].

Group activities are usually located in the garden’s polytunnel, just in case of rain. The panel above shows (lower left c’wise) examples of grain and flour, a ‘tasting’, making things with grain and other natural materials, an activity table for children and their grown-ups, and bags of grain from the garden with young scientist sitting on the rotary quern fascinated by oat grains.

Cooking with bere barley – more than bannocks

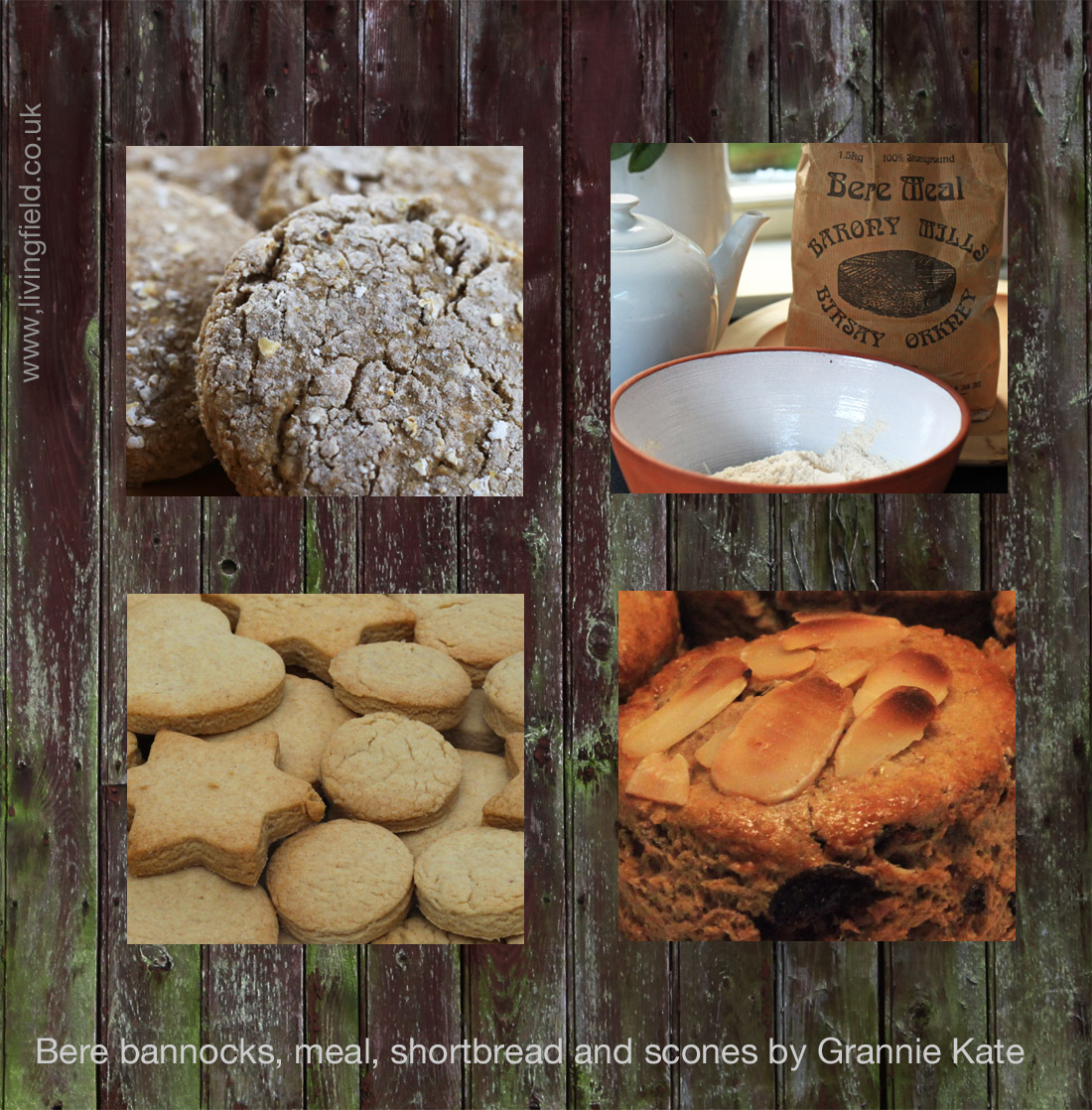

The thread linking exhibits through the years has been bere barley – Scotland’s barley landrace, an attractive plant, easy to grow. Bere as a crop declined in the late 1800s and is now restricted to a few fields in the far north. Like most of the world’s landraces, bere faded in competition with modern crop varieties and production methods. Yet it remains a favourite here. Its story continues [7].

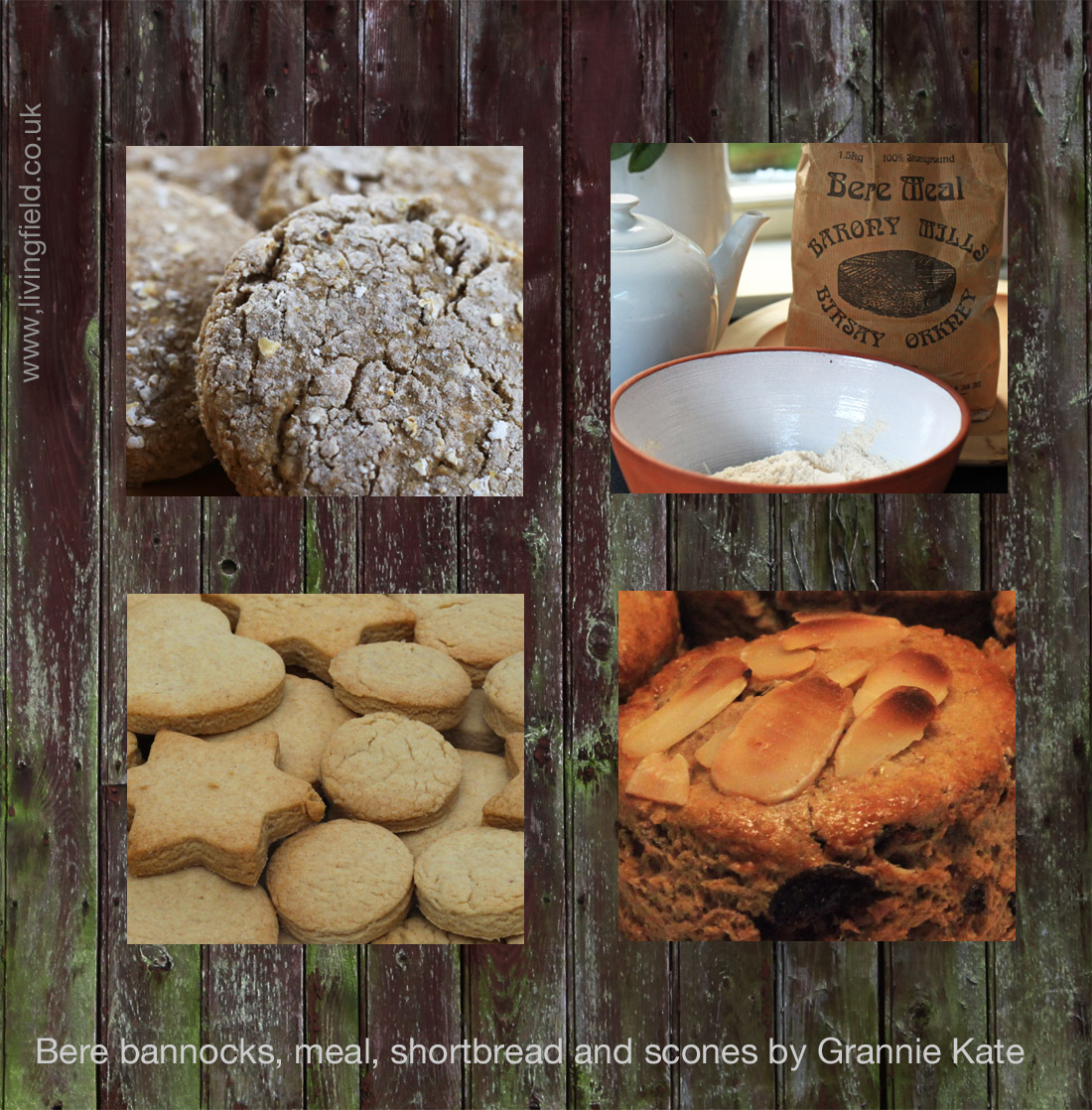

Bere and other barleys were traditionally used to make a flatbead or bannock, either on its own or mixed with oatmeal or peasmeal, but bere meal has many uses when mixed with other flours.

The Living Field has friends and correspondents like Grannie Kate who regularly experiment with different uses of ancient and modern grains. Scones, shortbread, batter, porridge, soups can all include bere as a unique constituent. One of the team regularly adds a a spoon or two of bere meal to their morning’s rolled-oat porridge.

The images above show (top left, c’wise) bere and oat bannocks, a bag of bear meal in Grannie Kate’s kitchen, bere fruit scones and bere shortbread [8].

On the road

Following the Living Field’s appearance at a ‘biodiversity day’ run by the Dundee Science Centre in January 2016, we were invited to join the exhibition trail organised in 2016 by the Centre as part of The Crunch [9]. By this time, we could take take the whole process on the road – seed-plant-grain-flour-food.

Gill Banks and Linda Nell, with Lauren Banks and Geoff Squire, ran the grain to plate events at The Crunch venues. One was in a darkened auditorium at the Dundee Science Centre, another at a local community Centre.

The Science Centre suggested we bring some bread made in the usual way from cereal grain and some made from insects. Gill bought various whole insects and flours and made some insect loaves that several of us had a pre-taste of and concluded they tasted just like nice wholesome loaves.

Anyway, the insects went down a treat at the events and started many a conversation of what we eat and what it costs – insects gram for gram need much less energy and cause much less pollution than most other forms of animal rearing.

The panel above shows scenes from the (top right) the January event) and bottom right (The Crunch) both at the Science Centre, then (top left, down) sheaves of spelt and black oat, globs of gluten extracted from wheat by Gill, mixed-flour bread with dried crickets laid on, and (at the bottom) dried insects for cooking or eating and (centre) barley grain.

Ancient grains in Living Field art

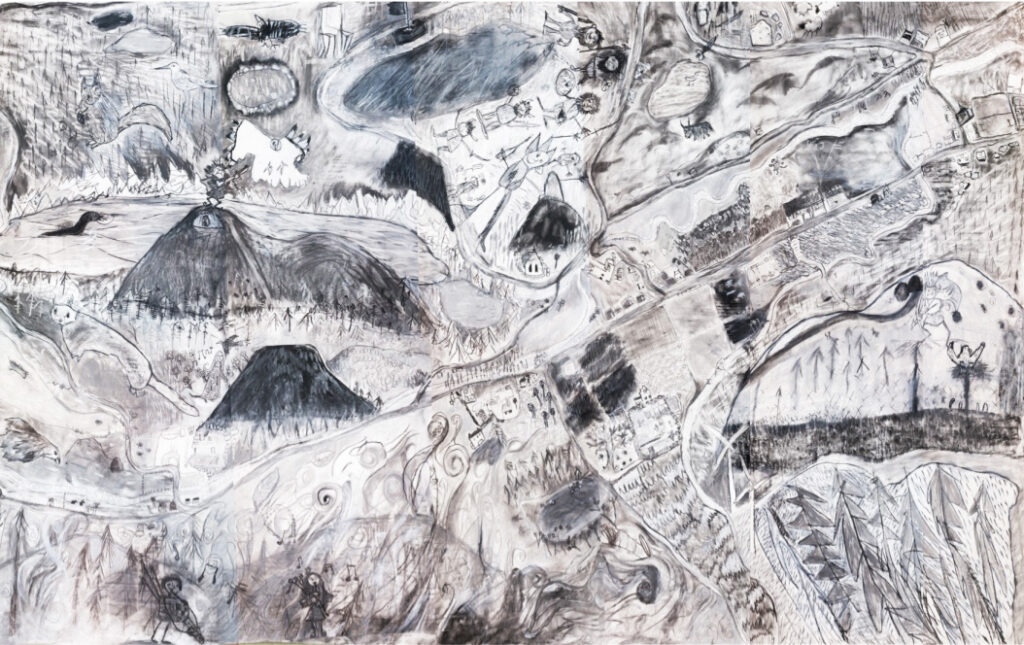

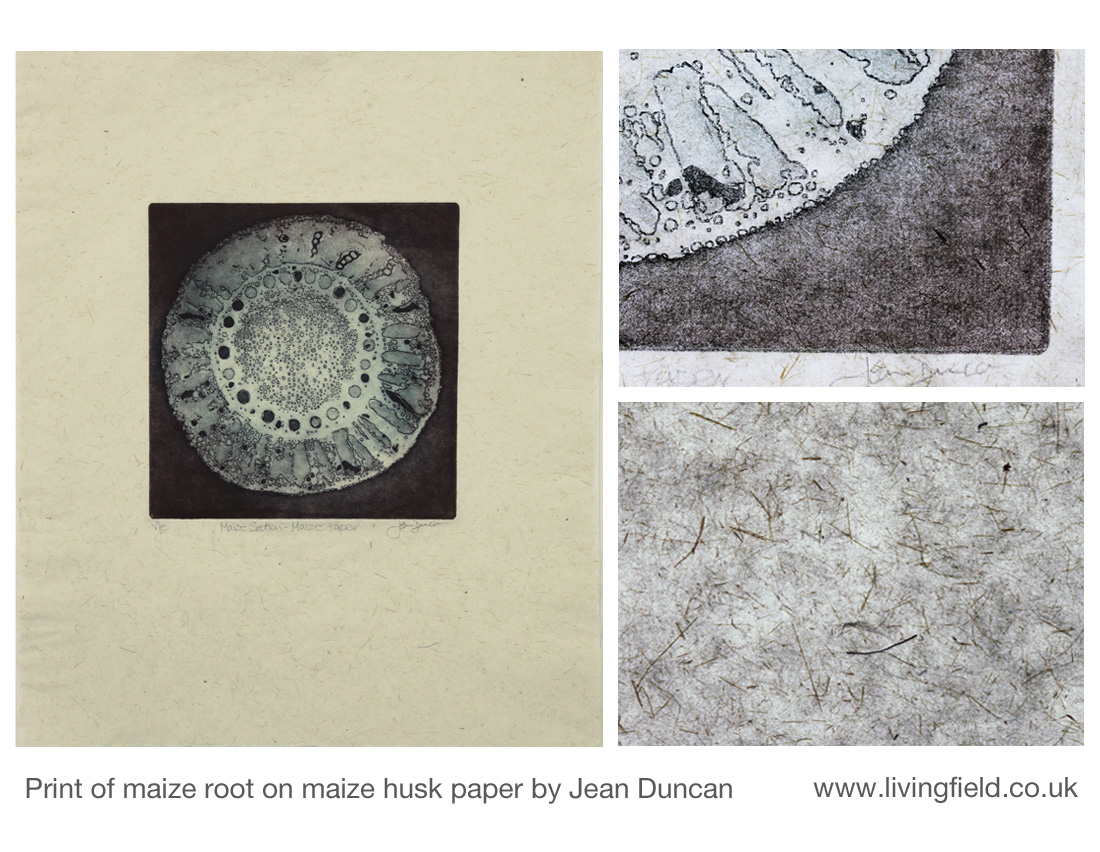

Through working with artists, the team were able to see the plants they had grown become part of artwork. Jean Duncan for example was able to place grain not just as a food but as essential to the development of farming and human society since the last ice. In her work, grains and plants appear close to circles, barrows, landforms and field systems.

Some extracts from Jean’s creations are shown in the panel above. Various ears, spikelets and grains appear commonly alongside mounds and barrows (example right). At top left, ancient cereal plants are stylised as fans, drawn near the centre of a circular design, used to create a revolving backdrop for an opera. At bottom left, a section of her ‘teaching wheel’ shows a range of cereal species grown in the region since the neolithic [10].

At Open Days, children like drawing things, messing with paint and pencil: better then just looking, it helps to give them a lasting memory of what they saw and touched.

Where next

Nearing the end of 2018 and the project will continue its work on bere and other grains, ancient and modern. The Living Field is connecting to the swell of interest in local food and recipes.

Few others can demonstrate the whole chain – not just grain to plate – but from sowing the seed to eating the food and, crucially, saving some grain for the next year’s crop.

The James Hutton Institute has recently been awarded funds for an International Barley Hub. Let’s see what the 2019 season brings!

…… warm bere and crickets?

The idea of ‘insect bread’ always raises interest, even if to some the thought is less than appetising. But insects and bread have a long history together ……

At one time and even now in many places, a bag of flour can have resident insects in the form of weevils. They live and reproduce in it, eat it and recyle it in one form or another (probably best not thought about). They add a little crunchy something to a baked loaf [11].

That’s insect bread ‘by accident’. For several years, and as shown above, Gill and Co have been experimenting with bread made from insect flour mixed with grain flour. The insects tried so far are mainly crickets, raised especially for the purpose (though not by us). Insects as alternatives to fish and meat in European diets is a hot topic now [12].

Sources, references, links

[1] Geoff Squire and and Gladys Wright developed the ideas around a seed to plate theme not long after the Living Field garden began in 2004.

[2] The Hutton farm staff have been partners in the Living Field since its making in 2004. They manage the crops, drive the tractors and explain what’s going on to visitors.

[3] Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson grow the Living Field cereals from seed each season. They have been helped by several other people in earlier years, especially Linda Ford.

[4] Thanks to Orkney College and SASA Edinburgh for giving the original seed. The Institute’s barley collection was the source of several landraces and varieties grown in 2015: see Barley landraces and old varieties.

[5] Gillian Banks experiments with bread making and has regularly baked a range of ancient grain loaves and biscuits for open days and road-shows: see Bere and cricket.

[6] Open Farm Sundays have been well supported by Hutton staff – Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson prepare and run the Living Field ‘space’; other regular contributors to the ancient and modern cereals theme include Gill Banks, Lauren Banks, Linda Nell, Linda Ford, Mark Young and Geoff Squire. Students and family have helped time and again on the stalls and exhibits. For more on LEAF Linking Environment and Farming, see LEAF innovation Centre.

[7] Bere barley and bere meal feature regularly on the Living Field web site, for example see the Bere line – rhymes with hairline, Bere country, and Peasemeal, oatmeal and beremeal.

[8] The Living Field’s correspondent Grannie Kate’s offerings mix bere with other flours, see Bere shortbread, Bere scones, Bere bannocks and Seeded oatcakes with beremeal. Barony Mills in Orkney also has a book of recipes.

[9] The Crunch was a UK-wide series of events held in 2016, coordinated locally by Dundee Science Centre: Gill and Lauren Banks, Linda Nell and Geoff Squire, among others, offered a range of exhibits on themes of grains and bread: see Bere and cricket, The Crunch at Dundee Science Centre. Thanks to DSC for inviting us to take part.

[10] Jean Duncan is an artist who has worked with the Living Field for many years. For examples of her work and links to her wider presence from the neolithic onwards, see Jean Duncan artist.

[11] Geoff reminisces – ‘lived once in a place where the flour bought to bake bread had live-in weevils; you could pick the big ones out, otherwise they got baked.’

[12] Crunchy bread made by Gill Banks from insect flour: photographs and details at Bere and cricket. Later, Gill, Geoff and Linda F found when investigating an infestation of weevils in grain, that insects in bread, whether by design or accident, bring a high-nitrogen (high protein) addition, insects being about 10% N by weight – little nuggets of protein in your low-N loaf!

Contacts: this article, geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com; growing the cereals, Gladys Wright has since retired from the Institute. Any enquiries through GS.