Nocni dialog, oil, 1964 by Vida Fakin. More on Vida ….

Month: July 2016

Bere shortbread

Ingredients

10 oz self-raising  flour ( not plain)

flour ( not plain)

1.5 oz dried semolina

3.5 oz bere barley flour

8 oz butter

5 oz castor sugar

and a pinch of salt.

I make shortbread biscuits regularly with my 3 year old granddaughter Ellie, who loves making a mess and ‘helps’ me.

Shortbread biscuits can be a bit dense so I always use self-raising flour (or a mixture of SR and plain flour). I usually add semolina to give a slight crunchiness to the biscuit. However, I had only a small amount in the bottom of the packet. So, I substituted bere barley for the semolina.

The resulting dough was too dry and so extra milk (or buttermilk to be more traditional) was added – about 2 tablespoons – so the dough could be rolled easily without it breaking up.

What to do

Preheat oven to 150 C or gas mark 2. Melt the butter or soften in the oven for a few minutes then cream the butter and sugar together ( use a hand held electric whisk) until the mixture is light and fluffy. Add all the dry ingredients, then mix again. Add milk to make the dough stick together.

Roll out the dough on a floured surface and then use cutters to make the biscuits into rounds or other shapes. Transfer to a greased baking tray or use baking paper and make small pricks in the biscuits using a fork.

Bake for 20 min then turn the trays around and bake for a further 20 minutes. Remove the biscuits when they are a light golden brown. This makes a good 40 biscuits or so, depending on the size of the cutter. Cool them (if you can) before eating!

Variations

Add a handful of dried cranberries or sultanas to the mixture before you roll it out. Little helpers love doing this, but often eat the fruit before it gets into the biscuit mixture!

Comments from the tasting panel

“Shortbread can lack body. The beremeal gives it serious character.”

“Good cohesive strength when wet – doesn’t disintegrate between tea-mug and mouth.”

“A real biscuit – you can taste the bere.”

“Can’t stop eating them…”

Sources, links

Recipe by Grannie Kate

Beremeal from Barony Mills Orkney

Links to pages on this web site:

More baking with bere barley: Bere bannocks, Seeded oatcakes with bere meal

The bere line – further links and pages on the history and uses of bere barley

Landrace 1 – bere – for information on the Orkney bere landrace

Bere, bear, bair, beir, bygg – variation on the name in Old Scots

Shetland’s horizontal water mills

Corn mills in Shetland, Orkney and the Western Isles; the horizontal water driven mechanism; locally managed and owned; bere and oat; the similarities of mills in in Europe and Asia.

“The praying machine of Thibet is, I believe, of similar construction.’ (Goudie, 1885-86)

Three small water mills, housed in stone huts, lie one below the other down a small waterway near Huxter in Shetland (HU 172572), west of Sandness and NW of Walls.

They must have been some advance over the saddle quern, which was still in use when Gilbert Goudie investigated Shetland’s horizontal mills in the 1880s. The mills were of a time when each family or group grew its own bere barley and oat and then ground it to meal, to eat.

The mills are small stone buildings constructed along a waterway or burn. They were locally made and owned, sometimes by several families. Goudie cites Evershed (1874): ‘No portion of the material is purchased, except a single clamp of iron”. The millstones are sourced locally.

The water is channeled off the waterway above the mill along a stone-lined lode (visible in the images below) which enters the mill to turn a paddle wheel under the floor. The mills are called ‘horizontal’ because the force of water turns the paddles in a horizontal plane, rather than vertically as in the later water wheels of the type at Birsay in Orkney.

The paddles drive a vertical iron rod, fixed so it turns the upper of two millstones (up to 3 ft diameter) in the room above. After passing through the paddles, the water then runs out to rejoin the waterway and on to the next mill.

There’s no sign of corn crops in this area today – it is all grazing. Yields of corn are uneconomical now and people can import their bread, rice and pasta from other regions, as do most others in the Atlantic croplands.

But what did bere look like? The photograph below shows a bere landrace from Eday, Orkney, grown in the Living Field garden in 2015. Bere in Shetland in the 1800s would have looked much like this – very different from today’s two-row types, but not quite a six-row barley.

But in the later 1800s, the people here probably grew mainly oat, as they did all over Scotland. But which oat – a landrace of the nutritious common oat Avena sativa or one of the black oat Avena strigosa? Those concerned with the industrial archaeology of the late 1800s rarely noted the crops.

Easier than a saddle quern

The mills were reported by Goudie to grind a bushel an hour. Depending on conversion factors, a bushel (volume) is equal to about 22 kg of bere – which is equivalent to about 15 kitchen-sized bags of flour or meal, though the actual yield of pure meal would be less because of all the chaff (husks, awns) that would have to be be discarded. So not a bad yield for an hour’s work!

Horizontal mills in history

Horizontal water mills had been in use for many hundreds of years when Goudie wrote his account. Both Goudy (1885-86) and Wilson (1960) point to the almost global occurrence of these machines, stretching from eastern Europe and Asia to Shetland and the Faroe Islands. Wilson illustrates characteristic types of mill wheel – Shetland, Irish, Alpine, Israel, Balkan – the design transferred in antiquity across the land masses of Europe and Asia, evidence of the connectedness of the northern islands to the wider world.

So how and when did they get to Shetland? These authors note that despite the similarity between mills in Shetland, the Faroe Islands and Norway, suggesting a common ancestry (9th C?), there is no evidence to confirm the direction of travel. Goudie also points to similar constructions in eastern Europe and Asia, and concludes:

“Almost obliterated as it is elsewhere, it is here still to be found in extraordinary numbers” and “… almost in Shetland only, that we find it in active operation …”.

One factor that hastened the loss of these mills was the (not untypical) action of a landowner, who constructed his own big mill, and then dissuaded families to abandon their small enterprises and pay for the use of his.

Certainly, the mills work no longer to grind meal, except as archaeological curiosities. The last one at Dounby in Orkney was taken over by The Office of Works in 1932.

But what a location! Imagine harvesting and milling bere or oat here on a fine day: sheep on coastal grazing, the Island of Papa Stour over the Bay and Vinland over an unbroken stretch of ocean to the west.

Sources, references

Main sources are Goudie and Wilson – both give diagrams of the mechanism

Goudie, Gilbert. 1885-1886. On the horizontal water mills of Shetland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 20, 257-97. Available online via the Archaeology Data Service: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/psas/volumes.cfm then click on Volume 20 and scroll down to a PDF of the article.

Wilson, Paul N. 1960. Watermills with horizontal wheel. Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (London). Titus Wilson & Son ltd, Kendal. Available online: try http://www.fastonline.org/CD3WD_40/JF/430/22-526.pdf

Further diagrams and general information

Further diagrams and general information

Cruden SH. 1948. The horizontal water-mill at Dounby, on the mainland of Orkney. Search: Archaeology Data Service / Archives (shows photograph of the Huxter Mills).

http://sihs.co.uk/features-waterwheel.htm

https://canmore.org.uk/site/69376/huxter-norse-mill

Another mill of similar type at Eshaness

http://www.heard.shetland.co.uk/Projects/Project8.htm

Fenton A. 1978. The Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland. New edition 1997.

Article and images, taken 26 June 2016: Squire / Living Field; except where stated by gk images.

[Last update 15 July 2016]

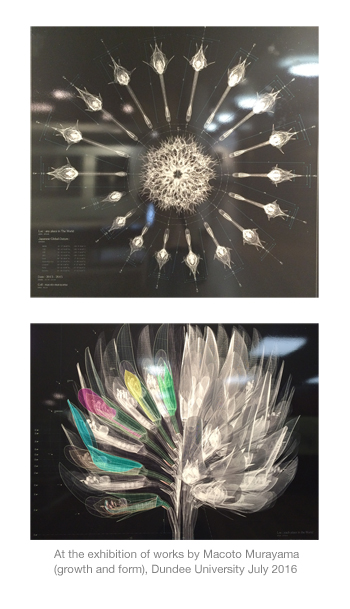

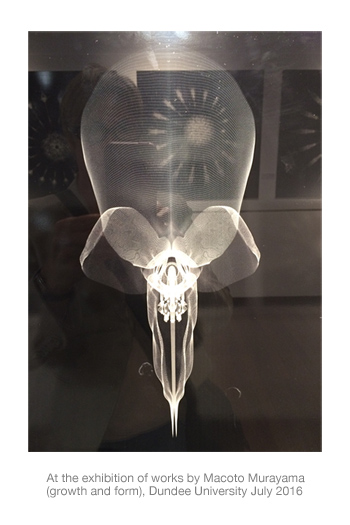

Macoto Murayama and T rep

T rep. The short form given by our field survey teams to white clover Trifolium repens. Still a common plant of pasture and waysides, so common that the intricacies of its structure and  function generally go unnoticed.

function generally go unnoticed.

Yet the mathematical artworks by Macoto Murayama shown in July at Dundee University reveal these intricacies in astonishing detail (image right).

The exhibition was held by courtesy of Frantic Gallery, Tokyo.

The Living Field’s correspondent gk-images sent some cellphone snaps from the exhibition.

The introduction gives some detail of the artist and how he transfers the complex flowering heads and flowers of his botanical subjects to two-dimentional images.

“Macoto Murayama is a Japanese artist who cultivates ‘inorganic flora’. His extraordinary images are created after minutely dissecting real flowers and studying [them] under a microscope. His  drawings are then modelled in 3D imaging software then rendered into 2D compositions on photoshop before being printed on a large scale.”

drawings are then modelled in 3D imaging software then rendered into 2D compositions on photoshop before being printed on a large scale.”

Born in Kanagawa, Japan in 1984 he is now a researcher at Institute of Advanced Media and Art and Sciences, Tokyo.

The photographs, with reflections of lights and the opposite wall are of white clover (top) and spanish broom (lower).

Sources, links

Dundee University – Macoto Murayama: Growth and Form Exhibition. 14 May to 20 August 2016. Lamb Gallery, Tower Building, Dundee. Click the link for opening times.

Macoto Murayama at Frantic gallery: http://frantic.jp/en/artist/artist-murayama.html

Frantic Gallery Tokyo. Looks like some great exhibitions, for example the Universe and other Oddities by Zen Tainaka.

On Growth and form, a classic treatise by D’Arcy Thompson. Web site http://www.darcythompson.org/about.html

Images Thanks to gk-images for the photographs shown here.

Ps Back to T. rep. There would be, in the 1940s, five or six legumes growing as ‘weeds’ in cornfields but they have since been ousted by nitrogen fertiliser and chemical herbicide. Trifolium repens is one of the the last remaining of these nitrogen fixers still found, but then rarely, in arable fields.