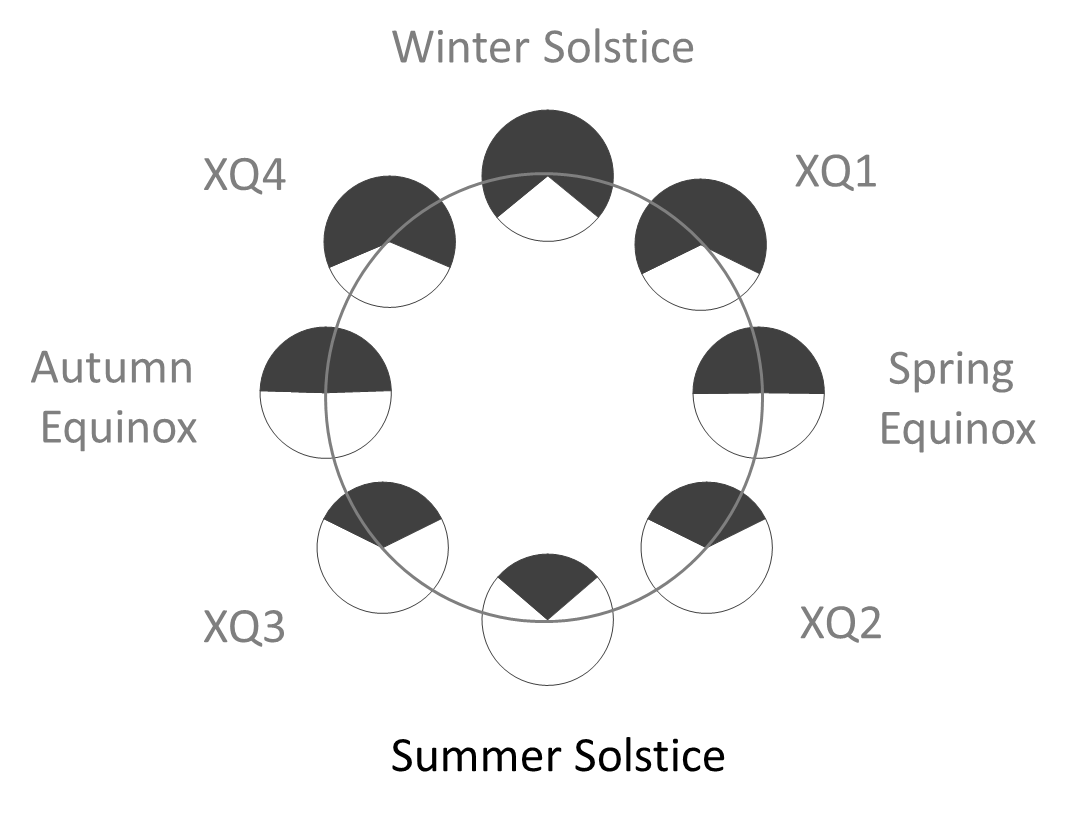

The summer solstice is the time of longest day and highest solar income. It occurs usually on 21 June each year but the daylength changes so slowly at this time that it would be difficult to tell which day was the longest without some form of complex solar calculator.

Images from the summer solstice

1 Fields of barley in flower, the main crop throughout much of the maritime east, now bulking under the high solar radiation yet still several months from harvest. 2 The legume and one time forage sainfoin Onobrychis viciifolia mobbed by bees at this time of year (LFG). 3 Flowering branch of the marsh thistle Cirsium palustre on old grazings, Invernesshire.

4 Flowers of viper’s bugloss, a striking plant but rare to see these days, one of the borage family (LFG). 5 Wet solstice roses growing in a hedge; midsummer damp hardly affects the wild rose – its petals curl to protect the inner parts, but don’t sog and rot like the old cultivated roses. 6 Bumble bee on field scabious flower (LFG).

7 Potato field in Strathmore, still some way before the rows close. 8 Flowering stem of field bean Vicia faba in Perthshire. 9 Opium poppy, some flowers full out, others gone, others still to come (LFG).

LFG = grown and photographed in the Living field garden. All photographs from the Living Field collection.

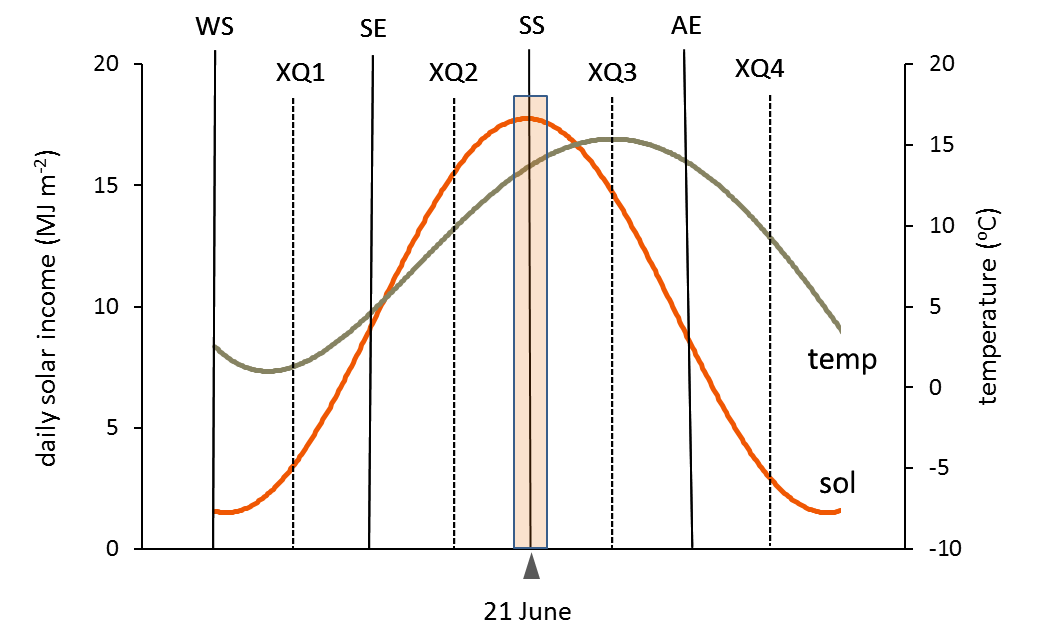

Solar energy and earth’s temperature

The solstice – the days are longest, the sun is highest in the sky, and if cloud stays away, the daily solar income is almost sub-tropical. Temperature is now moving towards its maximum. The weather can be glorious for people and for crops, yet cloud can move in any time from the Atlantic or from the North Sea and make it feel not much like summer.

On a clear day, the solar income reaches 25 on the left hand vertical scale in the figure above. It’s similar to the solar income in ‘cool season Africa’, but here the energy is spread over a longer period of the day, ideal for vegetation that’s bulking carbon.

The daily solar income will now fall, but on average temperature will still rise towards its maximum at XQ3.

Light and dark

The summer solstice is the time of longest day and shortest night. In clear weather, the light never dims completely.

On 21 June 2015, sunrise is 03.22 and sunset 21.06 at 58 degrees north.

The Living Field’s Energy and light: no life without the Sun shows the change in daylength over the year at various latitudes including Shetland, where the light hardly dims in late June.

The crops

The summer solstice has this feel of being the height of something. There is so much light, but the soil has been slow to warm, as have the big seas around the croplands, so even if the soil is warming the air is cool, and many of the crops are still not growing at their peak.

So while the summer solstice is a time of ‘stillness’ or minimal change in the solar cycle, it’s a time of great flux, change and difference in the crop cycle. Because the cool of northern latitudes slows our immigrant crops, most of them are not ready to take advantage of the sun, and in many years they waste it. Once the sun’s gone, it’s gone.

The readiness of autumn-sown (winter) crops

One way to get round this out-of-phasing in the solar and temperature cycles is to sow crops in late summer or autumn (called winter crops) in the hope they have enough leaf to capture the sun in May and June. The crops will need to be winter-hardy and they now mostly are. Winter oilseed rape – sown late summer the previous year – has flowered already, the yellow now replaced by dull green pods. The flowering ‘ears’ of winter barley should be visible, as might those of winter wheat.

Yet more than half the corn or grain crops here are sown in spring, late March and April, as are potato and most vegetable crops, still showing lines of bare soil between rows.

In the south of the UK and through the same latitudes in Europe, most of the cereals are now winter crops. So why not here? Why is there so much spring barley, amounting to half the tilled area of the croplands? It’s partly due to the risk of autumn-sown crop being set back in years with cold wet winters, but there is also a local market for spring barley in the whisky industry and as feed for farm animals. And grain yield of spring barley is still high, but without so much fertiliser and pesticide as given to the winter varieties.

Once the leaf canopies are well expanded, they can now take advantage of the long cool summer. The plants progress slowly through their successive phases, take a long time to fill grain and the potentially high solar income is spread over many hours so is unlikely to overload the plants’ photosynthetic system or cause heat stress (unlike in the tropics). In a good year such as 2014, the yields are high by most north-temperate standards.

The Traditions

Festivals, events, song , music around the winter solstice

Festivals and Events

The summer solstice is quiet compared to the colder quarter and cross-quarter days autumn, winter and spring. It’s a down-time in the crop cycle – sowing has gone and harvest is still a long way off but where there are sheep it’s shearing time.

- St John’s Day in the Christian calendar, 24 June, at the opposite side of the year from Christmas; just after the longest day, once celebrated more widely than today in many countries; fire festivals and dancing the night of 23rd.

- Ridings in Borders Towns, by horse, various times in June, originally to reinforce borders and ownership. Search web browers for ‘common-ridings-borders’ and enjoy a day out.

- Lanimer celebrations (Land Marches round boundary stones) in Lanark, held for a week earlier in June, with various goings on. See Lanark Lanimers.

- Alignment at Stonehenge: observance, communing with the universe, having a good time in the early morning.

- Of modern celebrations of solstice time, see the Solas Festival, of music and ideas, running since 2009 near Perth.

And in other places:

- New Year for the Aymara people in the Andes (their winter solstice) in Bolivia, Peru and Chile, having agricultural significance, looking to the increasing light in the months ahead. Search any web browser.

Songs and music

- The rigs of rye – rhymes with ‘the month of sweet July’ and maybe thats why rye occurs in far more songs and poems than you would think, given it was never much of a crop here. The lovers end up in Brechin ‘the winter through’ and Montrose in summer – not sure why! Great versions by Robin Dransfield, Dick Gaughan and the Clutha.

- Summer is icumin in – a medieval English round, has the cuckoo loudly singlng, which is about right for June in the north, as is the meadow in bloom, but the seed growing and woodland just in leaf are out of sync with the year; but nobody singing it cares. For a recent folky-rocky version, Richard Thompson on 1000 Years of Popular Music, viewable on YouTube.

- Rosebud(s) in June – ‘Here’s the ewe’s and their lambs, here’s the hogs and the rams, And the fat whethers too they will make a fine show’ is about sheep-shearing and gauging the year’s stock, among other things. Try Martin Wyndham-Read, The Watersons, or for a beaty version the Empire and Love album by Imagined Village.

[in progress June 2018]

Elsewhere in the World

The advancing summer brings dryness to the soil and air in much of southern Europe. These photographs from Umbria, Italy, show sunflower in full bloom and grass cut and hay baled ready for uplift and storage. There is an intimacy to the agriculture here, small fields, varied, well tended; many trees dotting the landscape.

At much the same time, the monsoon darkens the skies in south east Asia, but brings more than enough water to fill the rice fields. Here in norther Laos, villages are preparing fields and moving rice plants from small nurseries (lower right) to where they will grow and yield. Again, there is an intimacy here, groups of people tending small patches, working the soil with small motorised ‘ploughs’ and planting out the rice. Classic agrarian landscape.

Author/contact for this page: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

[Last update: 23 June 2018]