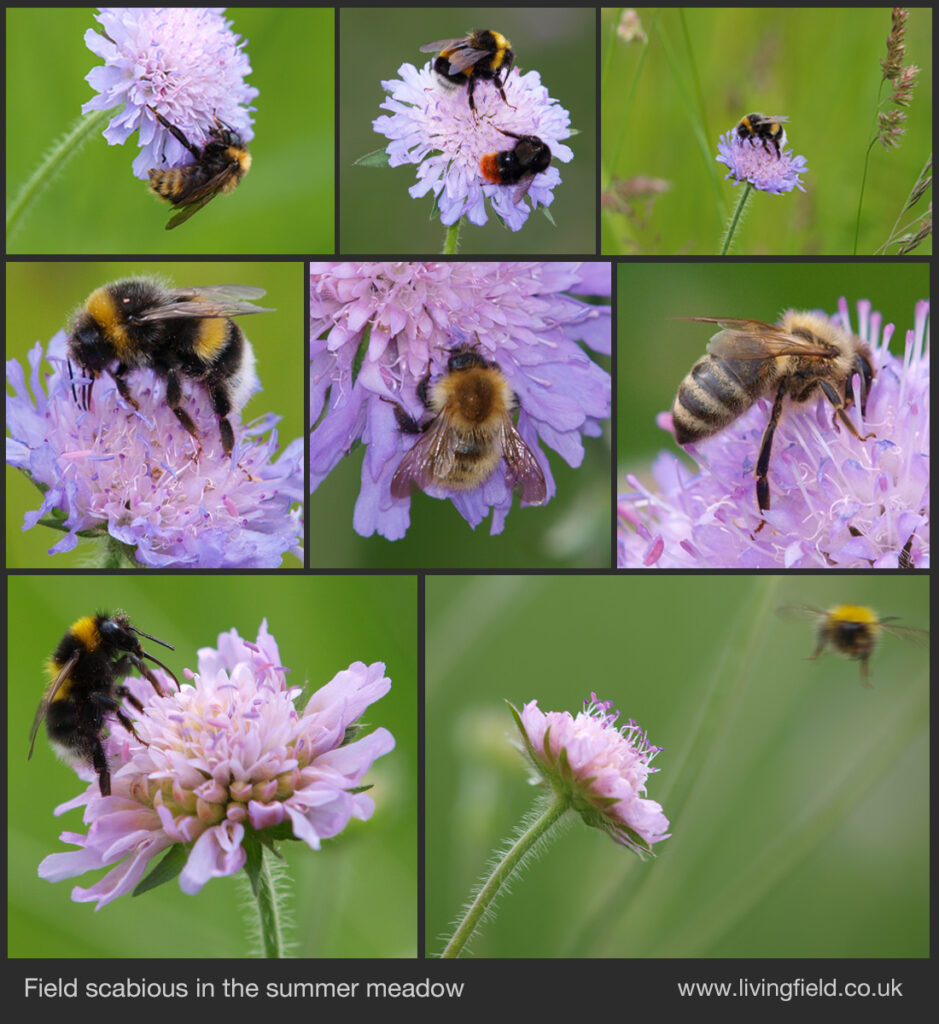

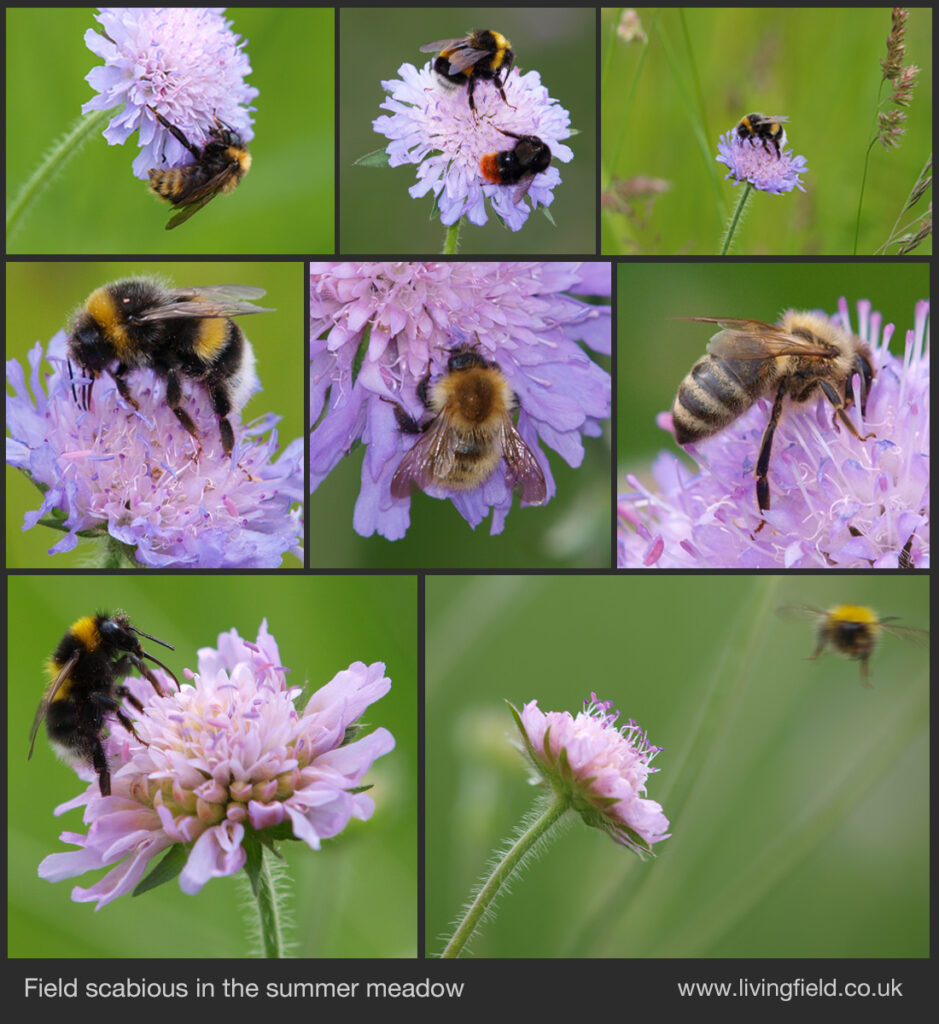

Field scabious flowers in the Living Field garden’s meadow for several months over summer and early autumn.

sustainable croplands

Field scabious flowers in the Living Field garden’s meadow for several months over summer and early autumn.

Want to help stop the widespread decline of bees and other airborne insects? Here are some notes on the Garden’s plants most visited by bumble bees, hive bees, hoverflies and the occasional butterfly. Most of these plants are easy to grow.

One of the main aims of the Living Field garden is to allow native cropland plants some space away from weedkiller treatment and competition with crops. Recent scientific reports have drawn attention to the widespread loss of invertebrate life and insect life in particular. The declines are happening all over the world.

Everyone who owns or manages land can do their bit to support flying insects. Here we show some of the Garden’s plants and plant groups that have offered food and shelter to flower-visitors over the years.

The legumes (family: Fabaceae), just ahead of the Composites, are the single most important group supporting wild flyers. The legumes as a whole offer probably the greatest variety and longest flowering season of all plant groups in the garden. They fix their own nitrogen from the air. All parts of the plant are high in protein.

Sainfoin, the melilots and lucerne were once grown or tried as forage crops in Scotland. The clovers, mainly white and red, are still sown, but the red is more commonly seen in the wild. The bumble bees’ favourite of them all is the blue-flowered, tufted vetch (lower images in the panel) – its strings of flowers produced for months on indeterminate sprawling and clinging stems.

Next are the composites (family : Asteraceae), each flowering head consisting of many individual florets. Not all species are equally visited, but the best here for pollinators are thistles and knapweeds. The great cotton thistle grows like a small tree, supporting large heads several centimetres across, bumble bees often bustling two or three to a head.

The greater and common knapweeds, hemp agrimony and tansy shown above are perennials, whereas the thistles in the garden tend to be biennial – germinating one year, overwintering as a rosette and flowering the next. The weedy perennial creeping thistle is too invasive in the garden’s small space and though it supports insects is discouraged in favour of other thistles.

Of all the species in the garden, field scabious (family: Dipsacaceae) is the one that offers sustenance to flyers for the longest period. A perennial, growing mainly in the meadow, plants put out flower after flower from early summer to late autumn (except in the very dry 2018). If there was one plant that we could grow for the bees, it would be this.

Teasel is a close relative that also grows well here. It self seeds and is mostly biennial. Plants are moved at the rosette stage in autumn or early spring to form clumps that flower in the medicinals bed.

The labiate family (Lamiaceae), including mints, sages, woundworts, deadnettles, hempnettles and basils – are well represented among the medicinals and herbs. They grow in sun, in shade and as occasionals anywhere. The large flowered types such as the herb sage are most frequently visited by the Bombus species, while betony tends to attract more of the smaller carder bees.

The smaller flowered species, such as meadow clary (a perennial n the meadow), fields mints, hempnettle and wild basil are less attractive to larger flying insects but have their own specialist range of inverts.

These are not the only plants that offer food and shelter for flying insects. Among the first in the year are the flowers and leaves on the garden’s native trees and shrubs. Early summer in the hedges, flowers of wild roses offer a welcoming landing platform for grazing hoverflies.

One of the longest flowering species, not shown here in the photographs, is viper’s bugloss Echium vulgare, one of the borage family. (See it at the Bee plants links below.) Borage itself and the comfreys are also well visited.

Populations of bees and other flower-visitors were very badly affected here by the dry 2018. There was little left in flower by the end of August, while in most years the field scabious and viper’s bugloss are still visited in late October.

The coming year’s weather is uncertain as always, but we’ll try to manage the plants to give the longest possible season to the resident insects and spiders. First out will be the willow ….. .

Nearly all the plants referred to here are native species or ones introduced long ago and now naturalised. Very few of the crops grown in the region (and the garden) – barley, wheat, oats, peas – support or need pollinating insects.

Oilseed rape fields provide a crop-based source of food for a few weeks early in the year and field beans also offer high-protein flowers much later. But the main sown crops and leys that could provide the right seasonal habitat – the legume forages and grass-clover mixtures – are rare and mostly long gone.

In the broader landscape therefore, the main source of food for flying insects lies in the broadleaf ‘weed’ species that live in crop fields and disturbed margins – in fact most of those shown in the panels above belong in this category. These arable plants, mostly not injurious to crops, have declined over the last century to the point where many of the plants themselves are now rare. It’s no wonder insects apart from pests are having a hard time in cropland.

The Living Field’s page on Bee plants give further notes and images of the individual species most frequently visited in the garden.

As usual, the plants are grown and tended by Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson with help from the farm.

The photographs of the insects on field scabious were taken by Linda Ford on an ideal summer day a few years ago, the others by Geoff Squire. Colleagues from the farm cut the Living Field meadow once a year and trim the hedges in sequence every few years to allow flowering and fruiting (e.g. for roses, willow, hazel).

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com

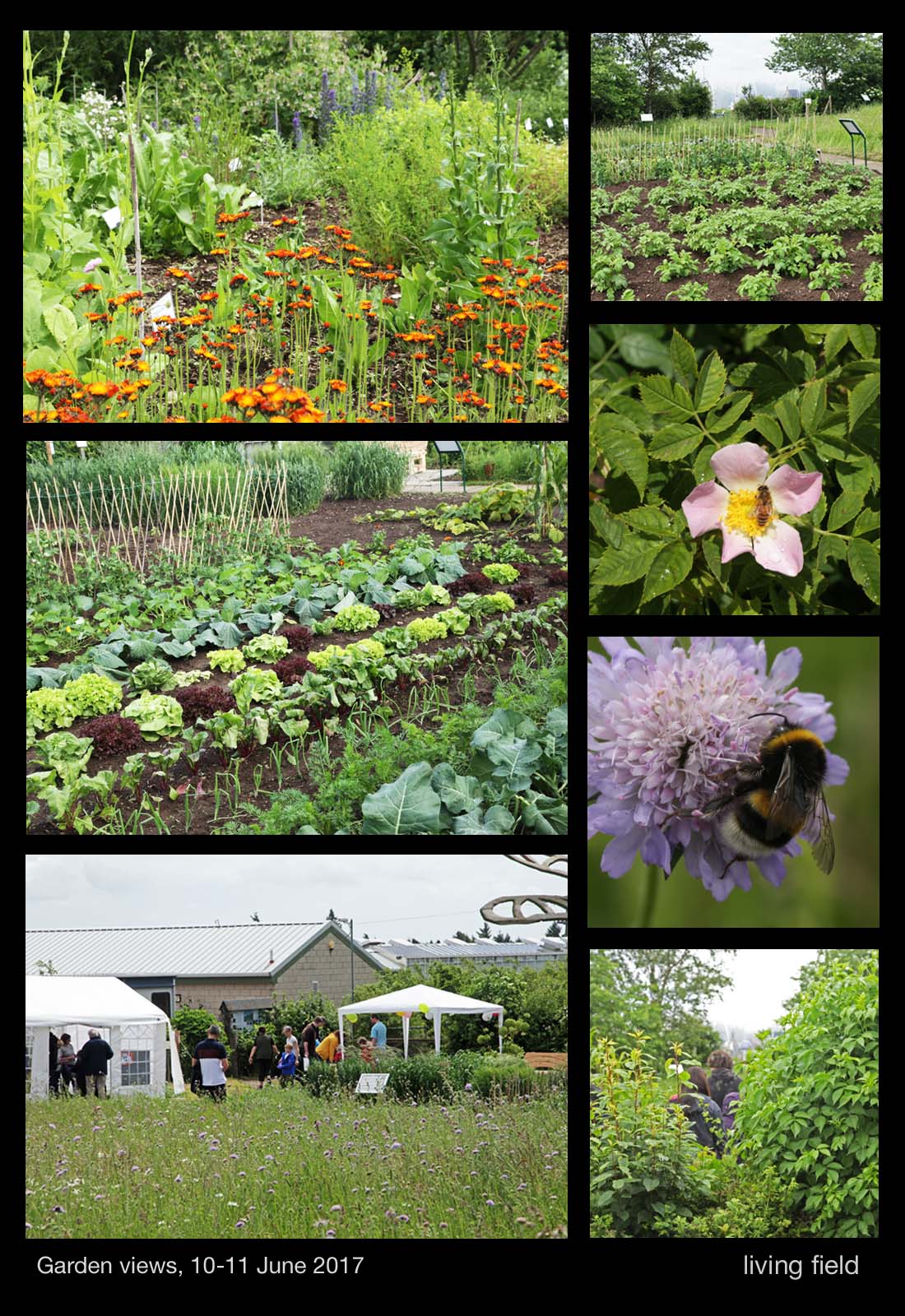

The Living Field Garden was looking good at Open Farm Sunday on 11 June this year. Despite wet weather, we had over 1000 visitors.

More on the Open Farm exhibits appears at the Hutton Institute’s LEAF web pages. Here we look at some of this year’s plants.

The hedges are thick with leaf, the hawthorn now filling its haws, the elder and the wild rose still in full flower. Water forget-me-not and wild iris are flowering in the wet ditch, while field scabious, comfrey and viper’s bugloss are offering plenty for the several species of bumble bees that live in and around the garden.

The three local species in the images above all reside in their own habitats, but are within a few seconds of hoverfly flight to the exotic maize in the arable plot. Maize originated as a crop in the Americas and was unknown in the country before the last few hundred years.

This proximity of the wild and the cultivated is one of the recurring features of the garden. The images above contrast the cropped area of the east garden with the perennial meadow and hedge plants. The field scabious in the meadow will keep the bees well supplied until late September at least.

Through the gate, the west garden’s raised beds are filled this year with vegetables and herbs. There are various cabbages and spinaches, parsley, thyme and dill, companion plantings and intercrops, to name a few, and all are intended to show the very different concentrations of minerals that these plants take from the soil and accumulate in their tops.

The background and results of this study, which is based on research at the Institute, will be covered in a future Living Field post.

We’ve been constructing various small places for insects and spiders since the garden began, but this year, the idea of a more permanent residents block was made real just before Open Farm Sunday. First stack your pallets, add a roof of turf and fill the spaces with small bespoke homes for our creepy friends.

Old logs and fence posts, with holes drilled in the ends, pine cones, garden canes, bricks with holes through, tubes, sticks, bits of rotting wood – all make ideal residences.

The garden made a return this year as the base for many activities at Open Farm. The cabins hosted exhibits on greenhouse gas emissions and nitrogen fixing legumes. The east garden, as you go in through the gate by the cabins, had a soil pit, cereal-legume intercropping, pest traps and the urban bug house shown above, while the west section displayed heathy vegetables, soil bacteria, our friends from Dundee Astronomical Society and Tina Scopa running a workshop on wild plant ‘pressing’.

The garden was maintained by the usual crew: Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson on the arable plots and raised beds; Paul Heffel from the farm kept the hedges in trim and cultivated the soil where required; Geoff Squire arranged the medicinals and dyes and kept an eye on various rarities and curiosities.

Gill and Lauren Banks, with help from the farm, constructed Creepy Towers, for which the ‘chimney’ was crafted by Dave Roberts and the plaque by visiting student Camille Rousset.

There is no formal funding for maintaining the garden – it happens through commitment and hard work, often out of hours.

Contact for the garden: gladys.wright@hutton.ac.uk

Unremitting wet since solstice-time in late June. The field scabious Knautia arvensis offers bee-food en masse for months in most years, and in June the mauve flowers promised a fine show, already thick with bumble bees.

Since then they have been thrashed by the heavy rain and wind and grasses now dominate the meadow. Yet on the rare sunny afternoon, the insects take their feast on the Garden’s wild plants.

Chief among them are the nitrogen fixing legumes, offering high-nitrogen, high-protein take-away. The images (above, top left clockwise) show white melilot, the blue-flowered tufted vetch, sainfoin, alsike and lucern.

Only the tufted vetch is common in the margins and lanes here. The others have been tried as forages in the past but are now rarely found. Other legumes flowering (not shown) include red and white clover, the yellow-flowering melilot and greater bird’s-foot-trefoil, all well attended by bees.

The other plants that most years offer months of rich flower-food fare no better.The striking, blue viper’s bugloss in the medicinals bed is almost finished bar a few, one of which is shown above right. And the remaining field scabious, bottom left above, will continue to put out their sumptuous floral parts for bees to drain and trash.

Yet again, the benefits of growing in this small space a diversity of native and medicinal plants pays, because teasel, knapweed and greater knapweed, and a set of annual composites including cornflower and corn marigold are all offering their wares in return for chance pollen.

Teasel will now flower along its bristly head for some weeks – the ladybird in the image top left above just slotting in between the spikes, jostling several aphids that may not be visible at this magnification.

What’s to come – the deadnettle family – the labiates – will sustain the insects through to the autumn equinox. Many are only just in flower – betony, wild marjoram, some field mints, hemp-nettles, a calamint, sage, lemon balm and hyssop.