The floods this past winter of 2015/16 were spectacular, lakes appearing where there were fields and swollen rivers coursing through the landscape. The soil was saturated for months and crops were damaged.

It was difficult to predict at the time the loss of grain yield at harvest. If a winter crop fails, farmers may switch to another crop such as the hardier oat. Or they may sow oat in spring instead of spring barley; or even not sow a grain crop at all. Only the ‘good’ crops might appear in the census. The trouble caused by the flooding might appear less than it was.

The first reliable indication is after harvest when the first estimates of the year’s yield are tabled. In 2016, the first estimates were published on 6 October and they suggested a smaller drop in yield than perhaps expected, smaller than the one following the floods in 2012. But we’ll wait until the final estimates are out in December 2016 before making final comparisons with that year.

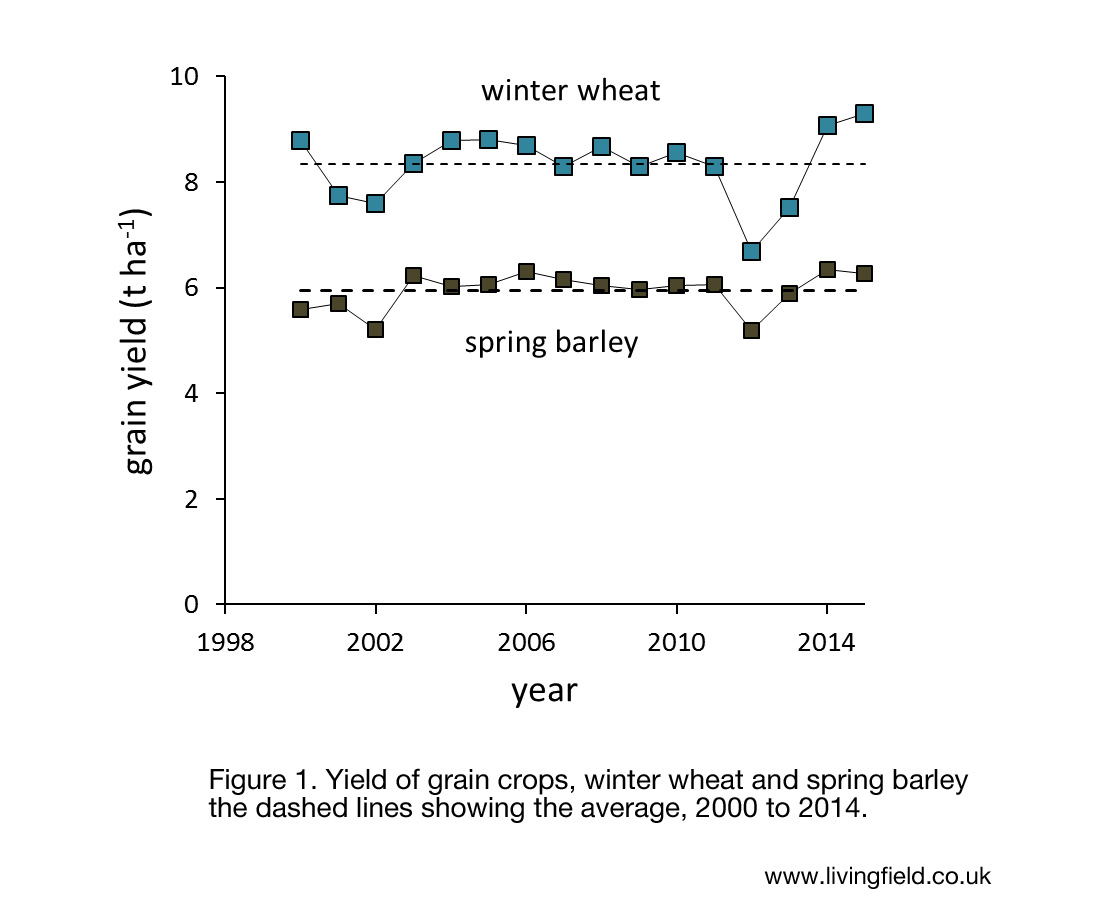

Here for reference (Figure 1) is a graph of national average yields each year from 2000 for the main grain crops, spring barley and winter wheat. In Figure 1, yield in units of tonnes per hectare (weight of grain per hectare of land, a hectare being 100×100 m) is shown in comparison with the average over the period represented by the dashed lines. Winter wheat yields more than spring barley, but the drop in 2012 is clear for both.

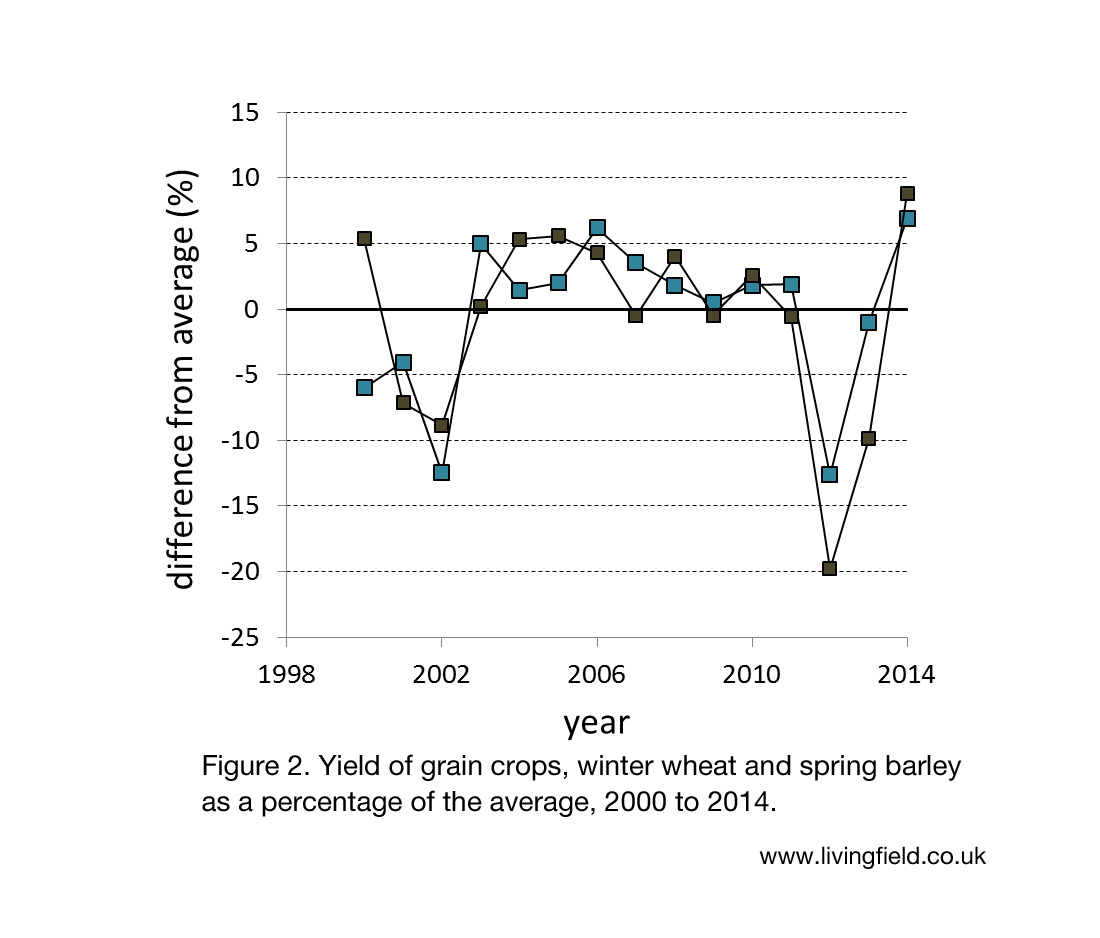

In Figure 2, the yields are shown as a percentage of the average (the heavier line at ‘0’ on the vertical axis). Both crops go up about the same and down about the same each year, but the drop in 2012 was bigger than anything like this in the last two decades. The wet cloudy year of 2002 also showed a fall in yield. Compare these with high yield of 2014 when the warm, sunny summer allowed the grain to bulk to a record for recent times.

Despite all the advances in machinery and crop varieties, farming in the north east Atlantic croplands is still very much at the mercy of the weather. Maintaining soil is good condition will be essential for future yields.

Further information and photographs of the 2012 floods on the Living Field web site at The late autumn floods of 2012.

Sources

First Estimate of the Cereal and Oilseed Rape Harvest 2016. Scottish Government. Published 6 October 2016. Link to a downloadable PDF file.