Legumes – best known here as the beans, peas, vetches and clovers – have sustained cropland and wild habitats by their ability to fix nitrogen from the air. Nitrogen is an essential nutrient needed by plants in large quantity for their amino acids and proteins. Without nitrogen, plants would not grow.

Legumes form a relationship – a symbiosis – with bacteria of the general name ‘rhizobia’, and it is the symbiosis in the nodules formed on roots that fixes the nitrogen. Nitrogen is released back to the soil when plants die or break down and when grazing animals, having eaten plants, drop dung and urine.

Through much of agricultural history, legumes and animal waste were the main forms in which nitrogen was made available to crops. Either legumes were grown with or before a crop such as a cereal, or animals were grazed widely on uncropped land and brought back to drop their waste near or on cropped fields.

But about 150 years ago, grain legumes such as peas and beans, and sown forages began to decline in sown area, and by the mid-1900s they had been mostly replaced by mineral nitrogen fertiliser and feed imports. These trends have major consequences for both food production, pollution and the country’s carbon footprint from agriculture (further information near bottom of page).

Main legume groups and species in the garden

Legumes are of the plant family Fabaceae (Papilionaceae). The garden grows grain legumes such as beans and peas, encourages wild legumes and keeps a collection of forage legumes that are now rare in the croplands. Examples are in the panel below.

Images: (top) white melilot with bee, kidney vetch, (mid, l to r) sainfoin, field bean, lucerne, (bottom) red clover and milk vetch in seed (Living Field collection)

Most of the legumes are invaluable to the invertebrate food web. Growing legumes is probably the most direct and immediate way to enhance insect wildlife including bees. Here are some of the plants.

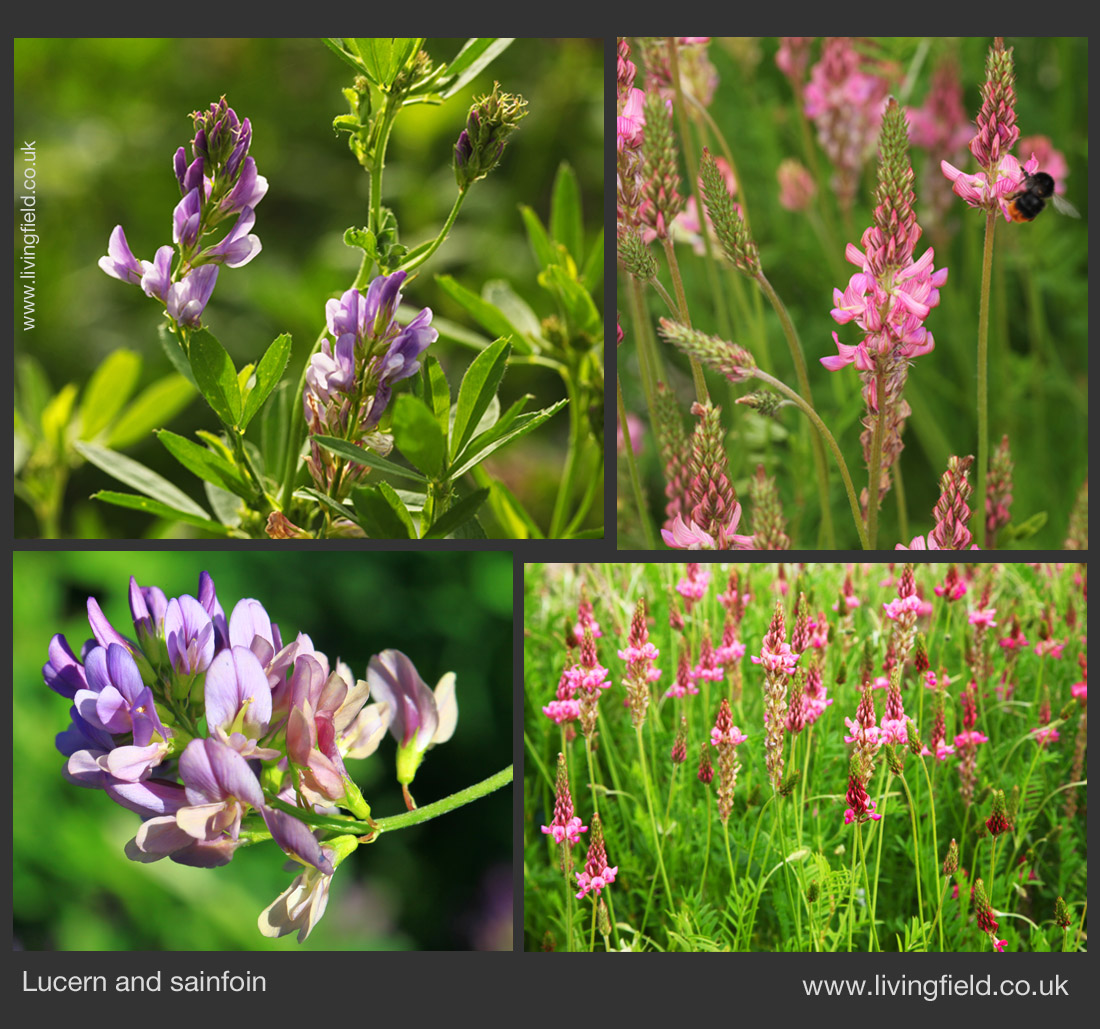

Forages – lucern, sainfoin, medics and melilots

Perhaps the main legume forage still grown as a crop (not mixed with grass) in Europe is lucerne Medicago sativa, which does well here, 0.5 m tall, winter hardy and vigorous, flowers blue-mauve to deep purple. Other forages tried in the north and growing in the garden include sainfoin Onobrychis viciifolia winter-hardy with the spikes of pink-red flowers, and the yellow-flowering common bird’s-foot-trefoil Lotus corniculatus and greater bird’s-foot-trefoil Lotus pedunculatus.

All are noted in Lawson’s 1852 Synopsis as potential forages. Lucern was still recorded in the agricultural census in the early 1900s. The others may still be sown in various bird and game mixtures. Sainfoin is occasionally seen as a relic, probably from recent sowings.

Forages – melilots The white melilot Melilotus albus and the yellow flowered ribbed melilot Melilotus officinalis represent another group of cultivated forages, which are also plants of waysides, waste places, railway sidings and dunes, but mainly in the south of Britain and mainland Europe. They grow almost into small shrubs 1 m or more tall, and hold their flowers on upright branches in racemes about 10 cm long. The melilots were tried as forages in the north as recently as the mid-1900s but are no longer found. Bees much preferred white melilot over the yellow. See photographs below and at Bee plants.

More forage legumes lower down the page …

Grain legumes

Peas and beans – together known as pulses – are grown in the garden most years. Both have foliage and grain that are high in nitrogen and vegetable protein. They have declined in area and importance since the late 1800s and are now minor crops here. Globally, they are among the most important crops and in many areas are essential for a balanced, healthy diet. North-west Europe uses great quantities of peas and beans for food and animal feed but imports most of them.

The three main pulses grown here are pea, field (or broad) bean and phaseolus bean.

Pea Pisum sativum grows shorter than the faba bean or broad bean, and has tendrils that link plants to give them some cohesive tension. Harvested peas are sold for fresh produce, canning and processing. Some are ground in a mill to make peasemeal, a pea flour. Images above show a growing crop (lower right), a flower, usually self-pollinated and from which a pod develops (bottom left) containing peas, each connected to the ‘hinge’ in pod wall, and (top right) harvested peas. Pods remain green during filling of the peas and provide some of the energy and carbon needed for their growth, the rest coming from the plant’s leaves. Nutrients are translocated from the soil, through the roots, up the stem and along the hinge of the pod to each individual pea.

The field bean or faba bean Vicia faba is grown in the north as a field crop mainly for animal feed. Unlike many of the genus Vicia it stands upright by itself. The more familiar gardener’s broad bean is a variety of the same species which tends to have fatter, longer pods and bigger seeds. Field beans and also peas were once, and still occasionally are, grown with a cereal crop such as oats as a mixture called mashlum.

Beans of the genus Phaseolus are also well known to gardeners in the form of the french bean and runner bean, for example, but they are hardly grown in the north as a field crop. Varieties of the various species are grown in most but not all years.

N-fixing shrubs

Several leguminous shrubs are common throughout the lower cropland and higher grazing land, yet few people appreciate they are

nitrogen-fixers. Whin or gorse, two common names for Ulex europeaus is the spiny shrub that you might think would be the last thing that farm animals would eat, but when suitably pulped in a whin mill, was once a nutritious addition to their diet, and gave clearing whins more of a purpose. The plant gives a yellow dye. Broom Cytisus scoparius is about the same size as whin and commonly grows in the same places, but lacks the spininess. There are usually some plants within a 100 m of the garden.

Dyer’s broom or dyer’s greenweed Genista tinctoria grows in the dye plants bed. It was raised from seed with some difficulty, but now withstands even severe winters. Its flowers and foliage are similar to those of broom (see Garden/dyes).

Now back to forages …

Forages – clovers, vetches and vetchlings

Of the forage legumes, those grown with grass and other plants in hay meadows to be grazed or cut and stored for feed, the clovers are perhaps the best known today. White clover Trifolium repens is one of the hardiest, is still widely sown with grass mixtures and reappears in many arable fields as a reminder of the time when many fields rotated arable with grass. Red clover Trifolium pratense is larger but less persistent and hardy, and typifies the traditional meadow-clover to many people. The other clover kept in the legume collection is alsike Trifolium hybridum which finds it hard to survive the winter in the garden. Bees like the first two, but if both were in flower together, they preferred the red.

In the images above, top left is in the Garden’s meadow, red clover growing with bird’s-foot-trefoil (yellow) and assorted grasses; top right, alsike flower head with bee feeding; bottom right, red clover, carder bee alighting; and red clover.

A special favouriteis kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria, the one with the characteristic ‘ball’ heads, wooly beneath the protruding flowers (above). It too was listed in Lawson’s synopsis as a promising forage but has not been grown widely. It is recorded as a wound-herb, along with plantains and woundwort. Its wild forms live by the Angus coasts and are very short in height, also home to the small blue butterfly (see Links below).

Plants of the genera Vicia and Lathyrus have been grow as forages at various times. The commonest in the garden, both turning up wherever there is the space, are tufted vetch Vicia cracca, growing into a mass of leaves and tendrils supporting blue strings of flowers, and common vetch Vicia sativa, a small plant not hard to miss. A packet of seed bought as something else turned out to be hungarian vetch Vicia pannonica which grew vigorously at first, then disappeared after a couple of years. Yellow vetchling Lathyrus pratensis, scrambling with yellow flowers and milk vetch Astragalus glycyphyllos (images above) are both grown in the legume collection but are probably absent in 2018.

Legume weeds of cropland

Wild legumes are now so scarce in cropped fields that it may be hard to image that several of them were once common in fields and two in particular were troublesome agricultural weeds.These two can be seen in the garden in some years. Common restharrow Ononis repens must have gotten its name from its tough thick, stems and rhizomes that once made ploughing by hand or horse such effort. When grown a few years ago in the sown legume collection in the west garden, it was luxuriant, about a metre tall (images right below) very unlike the short plants of the same species that occupy scrub and coastal grazings (see Links below). Restharrow is still found in a few places in farmland within a few miles of the garden.

The hairy tare Vicia hirsuta looks nondescript, small leaves and small mauve flowers, but has these gripping tendrils (image above left). It is easily missed in the meadow or in cereal crops, but it grows fast and hangs on to crops and grass stems, twines among them, dragging them down, and bringing problems at harvest. It grows all over the place in the garden.

Management in the garden

Several of the legumes are local and found their way into the garden over the years – among which are red and white clovers, common bird’s foot trefoil, hairy tare, common vetch, tufted vetch and yellow vetchling.

These wild, local legumes are not managed in any way. They most likely found a niche as the fertility of the soil declined over the first few years without fertiliser. Once the legumes begin to nodulate, they fix their own nitrogen from the air, and release some of it for other plants.

Grain legumes are raised from bought seed, but not every year. The legume forage collection has been kept on raised beds in the west garden but is not grown in 2018. Seed of each species was sourced from various suppliers of natural forages. Sainfoin, alsike clover, greater bird’s-foot-trefoil, black medic, milk vetch, kidney vetch, the two melilots and lucerne were all raised in this way.

Most except the melilots appear to be perennial in this environment, but a few of them die away in the winter and do not return. Kidney vetch and red clover self-seed prolifically.

Legumes vs industrial nitrogen manufacture

The phase of agricultural intensification between 1950 and 1990 drove a major increase in crop yields, but the nitrogen fertiliser needed came not from legumes but from the Haber Bosch industrial process. It wbecame cheaper and less troublesome to buy bags of fertiliser than to grow legumes, and so the areas sown with legumes for grain (peas and beans) and forage (vetches and clovers) declined throughout Europe. In Scotland, as indicated above, the decline was well under way in the 1880s, before mass production of mineral N, possibly because of the preference of clover-grass mixtures over sown legume-only forages.

The change from legumes to bags of mineral fertiliser had massive global consequences. Nitrogen fertiliser is now recognised as a major global pollutant of air and water both during the making process and when applied to land. Following restrictions on when and where nitrogen fertiliser can be put on fields, the total nitrogen used declined from its peak in the 1990s, yet it remains very high.

The croplands rely heavily on imports, both of nitrogen fertiliser itself and nitrogen-rich protein needed to feed farmed animals and fish, which is bought in from the Americas. Without these imports, agriculture as now practiced would collapse. There is therefore a renewed interest in legumes, their nutritional qualities and their contribution as a fertiliser.

Links to related material on the Living Field web

Pulses (peas and beans) and their contribution to nutrition:

- Feel the pulse – a travelling exhibition

- Scofu – an indigenous Scottish tofu

- Peanuts to pellagra – nutrition combats deficiency

- Beans on toast – a critical look at the composition and environmental footprint of this meal

Pulse growing in the croplands:

- Mashlum – a traditional mix of beans and oats

- Can we grown more vegetables? – the vegetable map of Scotland

Articles and posts on legume species or rare habitats:

- Fixers 1 – coastal wild legumes

- Kidney vetch and the small blue

- Fixers 2 – restharrow on the dunes

and not least ……

- Bee plants – many legumes support bumble bees