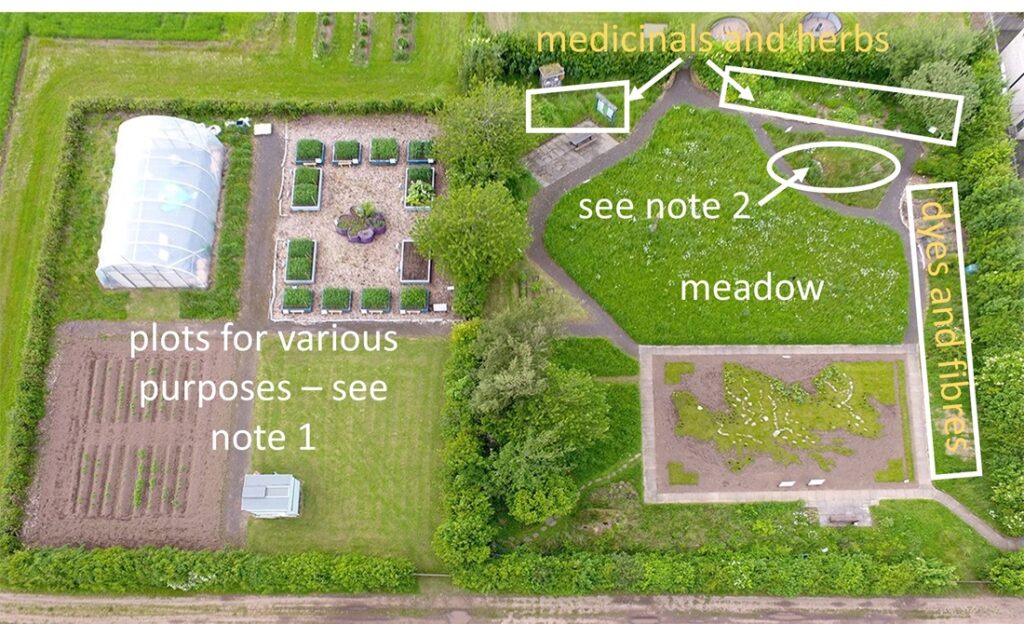

This note is for those folk at the James Hutton Institute who are hoping to restore the Living Field garden’s various beds and plots. The first photograph below is a drone’s view of the whole garden provided by The Farm several years ago.

The garden displays (1) habitats of farmland such as meadow, hedge, wood, pond and ditch, and (2) plant exhibits or collections including medicinals, dyes, cereals, legumes and vegetables.

The garden is divided by a hedge with occasional trees running top to bottom in the centre of the image. The right hand (or eastern) side was created first. The left hand side was added a few years later.

Left side

The left side of the garden contains a polytunnel (top left), observatory (bottom centre) and three plots (top right, lower left and lower right) that have been variously used for short-term collections or crops. The plot top right has 12 raised beds that have been used for a legume collection and then for herbs and vegetables. For some years, a wildflower seed mix was established on the lower left plot. It was later cultivated for potato varieties.

The left side was well used during open events when the polytunnel was filled with various exhibits and entertainments. The lower-right plot was usually kept as mown grass (as in the image) on which visitors could relax and enjoy the sun!

Right side

The right side of the garden in the image contains most of the habitats and the collections of medicinals and dye plants. Medicinals and some culinary herbs were grown mainly in the two areas at the top immediately adjacent to the hedge separating the Living Field garden from the met station to the north. The arrow pointing left indicates an area that was not weeded routinely but contained several perennial medicinals near the notice board and seating. The arrow pointing right indicates a weeded bed containing the annuals, biennials and less robust perennials. Information on the species is given at the Medicinals page. A couple of willows growing at the top right of the medicinals section needed to be pruned heavily or else they shaded-out the nearby plants. They might need to be cut or reduced, but at least one willow should be left to demonstrate the link: ‘Salix – salicylic acid – aspirin’.

Note 2. This small plot contains the toad hotel and usually a few wild grasses and legumes. It was not cultivated.

The meadow is at the centre of the right side. It was cut once each year, and the hay removed, but otherwise left to allow the species mix to shift with age. It transformed itself from mainly annuals and biennials in the first few years to a mix of perennial grasses, legumes and other dicots. Occasional invaders (e.g., docks) were individually removed. Species are described at the Meadow.

The beds to the right hand side housed dye plants and a few fibres, mainly flax. The Dye plants include perennials such as madder and dyer’s greenweed, biennals such as woad and weld, and annuals such as dyer’s coreopsis and chamomile. The biennials usually self-seeded but the annuals had to be re-sown each year.

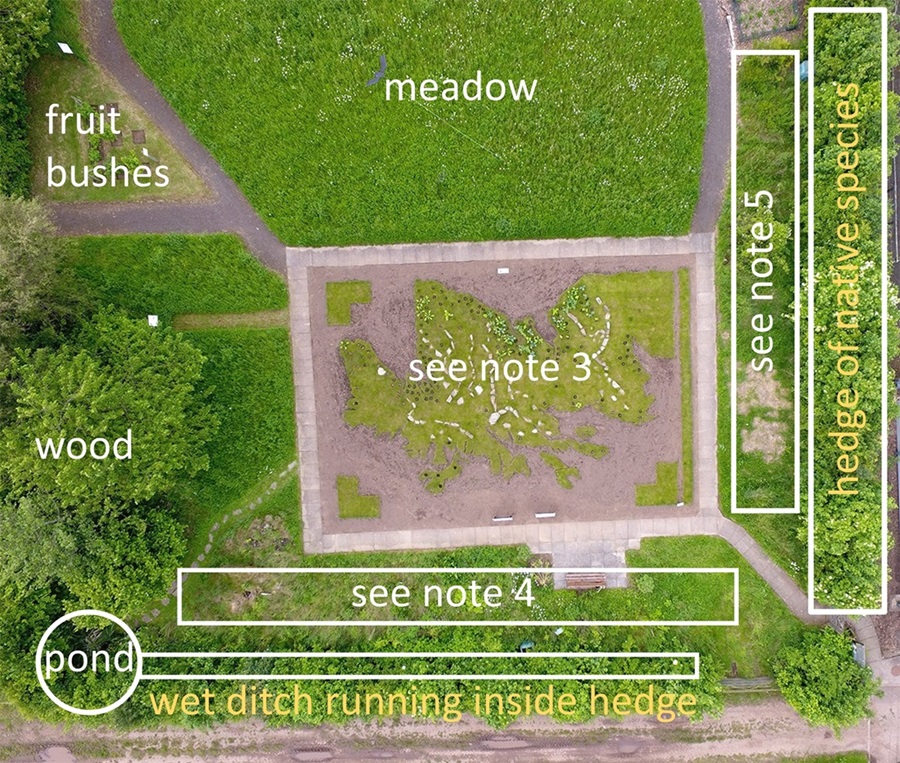

The rest of the beds and plots are shown in the diagram below, a drone image of the right side of the garden from the lower hedge to half way up the meadow.

Note 3. This rectangular area was originally reserved for the Ancient Grains collection and various leaf and root vegetables. It was converted a few years ago to ‘the map’ (see Vegetable map made real).

The Pond and Ditch were constructed as habitat for those plants of farmland that like wet soil or standing water. Many of the plants here, including meadowsweet and wild iris, had traditional uses, generally as medicinals, culinary herbs, drinks or fibres.

Note 4. This area, between the ditch and the map, was mostly left wild, except to remove the occasional aggressive or poisonous invader. One of these was ragwort, but a few plants of it were left to flower for demonstration. This area also became a temporary or permanent residence for a range of plants that tended to move from other parts of the garden. Among them were wild carrot, burnet and some forage legumes.

Note 5. This area was the lower end of the dyes and fibres bed but was for many years not cultivated. It was used on open days for visitor information and a tent or gazebo.

The area marked ‘wood’ contained a few local species that were allowed to grow into trees, e.g., rowan, gean, birch. The plants under the trees were generally unmanaged, but after a few years formed a typical woodland understorey.

The perimeter of the garden was planted with a hedge of local woody species. The hedge was not generally cut completely every year. For example, one side would be cut in one year but not the next and vice versa. Species are described at Hedge and Tree.

Weeding and letting be

Consistent decisions were made as to which areas should be cultivated and which not and also whether to welcome plants that came into the garden or to remove them.

The plots used for annual displays of, for example grain crops, needed the soil to be cultivated and were kept mostly free of weeds. In contrast, the habitats took care of themselves and were hardly touched once they were established, except where stated above, for example when hedges were cut and the meadow mowed.

The most challenging areas were the beds grown with medicinals and dyes. Many of the wild plants in these categories are also regarded as ‘weeds’ in some circumstances. There was always a balance between keeping them as exhibits, but preventing them spreading or out-competing their neighbours. Garden angelica for example forms a majestic structure in its second year, but disperses a mass of progeny on all surrounding bare soil. And betony seemed to be contained in the first few years but then its seedlings began to appear in too many places.

But the worse by far has the name melancholy thistle Cirsium heterophyllum. It certainly created a deal of melancholy in the weeder, spreading underground as it does, then appearing in and among clumps of our prized medicinals. It had to be rooted out at least twice a year. And the strange thing is that we did not sow or plant it knowingly. Rather it arrived in a packet from a seed merchant under another name – another composite of similar flower colour.

Most arrivals were welcomed however. Once the agricultural soils had been reduced in nutrients through offtake by the sown plants, many species that are uncompetitive when growing with the likes of thistles, docks and nettles found themselves a welcoming refuge in the garden’s habitats.

For example, marsh woundwort appeared near the pond and several vetches joined the grasses in the meadow once they had ousted the initial annual mix. Perhaps the most spectacular was the giant cotton thistle Onopordium acanthium that appeared of its own accord and flowered tall at the first open day (see Cotton thistle and Big Daisy).

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.a.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com

[updated with minor edits 31 October 2023]