From our correspondent …

In Highland Region, at latitude 57.46 N, in a cool temperate climate, lies Inverness Botanic Gardens [1]. It combines in its small space, education and community growing with displays of local and exotic plants …. and a cafe .. CafeBotanics. It lies on the west side of the River Ness, just south of the town centre and close to the new southern ring road.

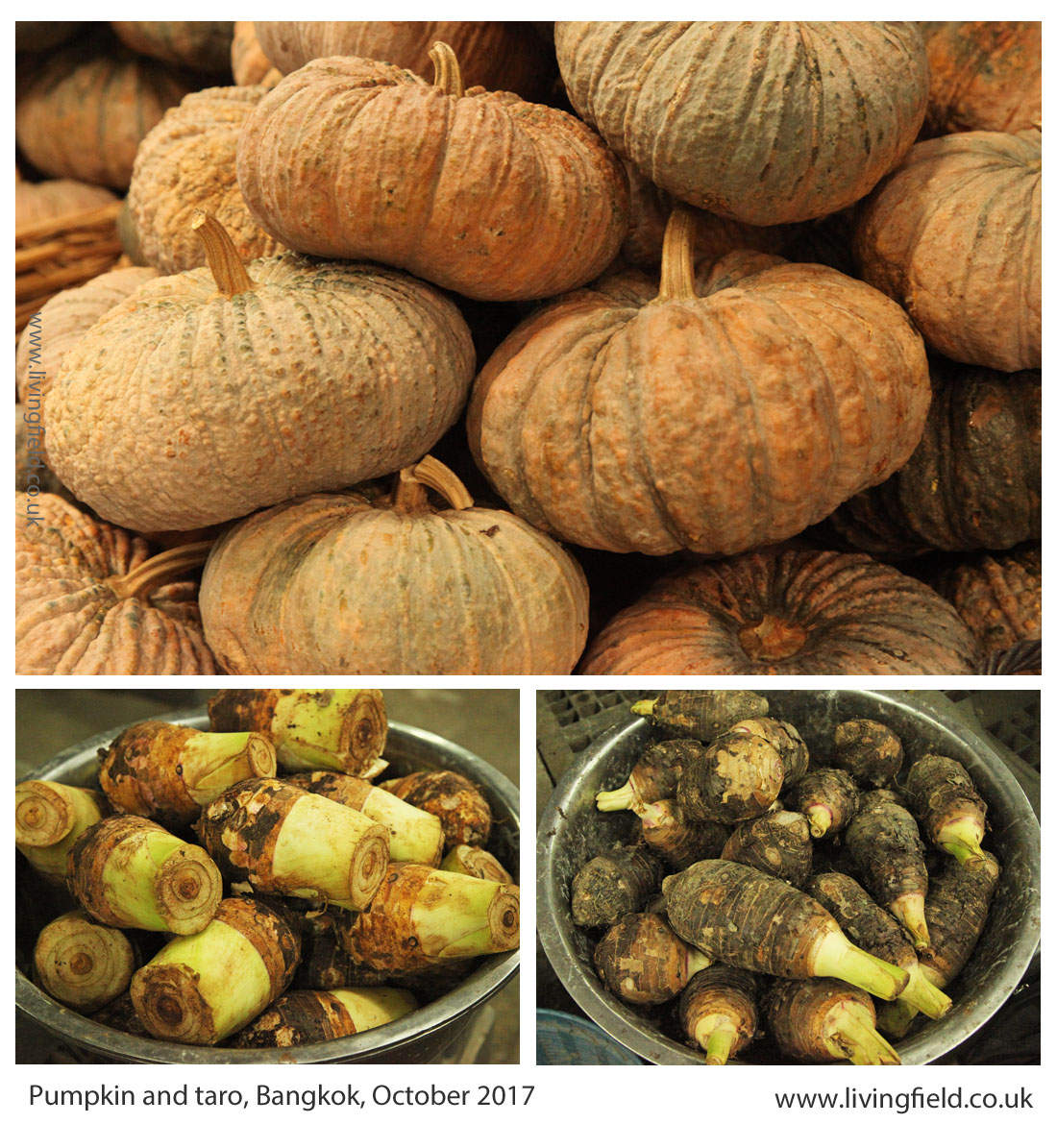

Pass through the cafe, enter the glasshouses and marvel at the collection of tropical plants. Follow the signs along a path to the community hub – the G.R.O.W project – which practices horticultural therapy. There’s grass to play on, a collection of herbs and vegetables and an outdoor insect-house.

The garden was opened in 1993 and revamped in 2014 [2]. It’s now open to the public every day each week, admission free, donations welcome.

The Living Field appreciates the blend of education, outreach and botany. But first – and especially for those who haven’t yet visited the region – some notes on the local climate. Is it warm and sunny enough for a tropical glasshouse?

The Climate (outside)

57N has a reputation in the UK – cold and gloomy, cloud and wet! Not at all! Weather is relative – it depends what you are used to and what you mean by gloomy …. and wet. From spring to autumn, there’s plenty of solar income, warming the ground and giving plants the energy to grow, and providing what is, by many standards, very good growing potential.

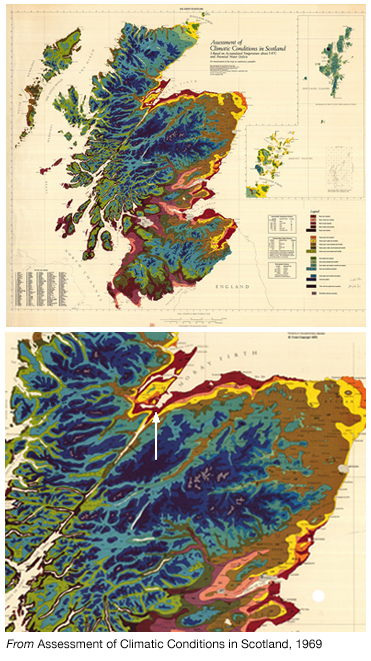

Fig. 1 Map from Assessment of the Climatic Conditions of Scotland produced 1969 by the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, now the James Hutton Institute [3]. The white arrow in the lower selection points to Inverness. The red zone is the warmest.

Good growing conditions? Yes, providing there is enough rain to wet the soil but not drown it (which there is) and the soil and air are warm enough to allow plants to thrive and survive (which they are).

The average air temperature in the main summer months is usually 13-14C. The average daily minimum in winter months is just above zero. And while temperature usually falls below zero on several days each winter, there is rarely the prolonged, deep cold of winter farther inland. In the map in Fig. 1, Inverness Botanics lies within the warmest climatic zone – the dark red and yellow areas that fringe the eastern coast.

The equable climate is determined mainly by a high solar income over the summer months and proximity to the nearby firth and sea which moderate temperature so it is rarely too cold or too hot.

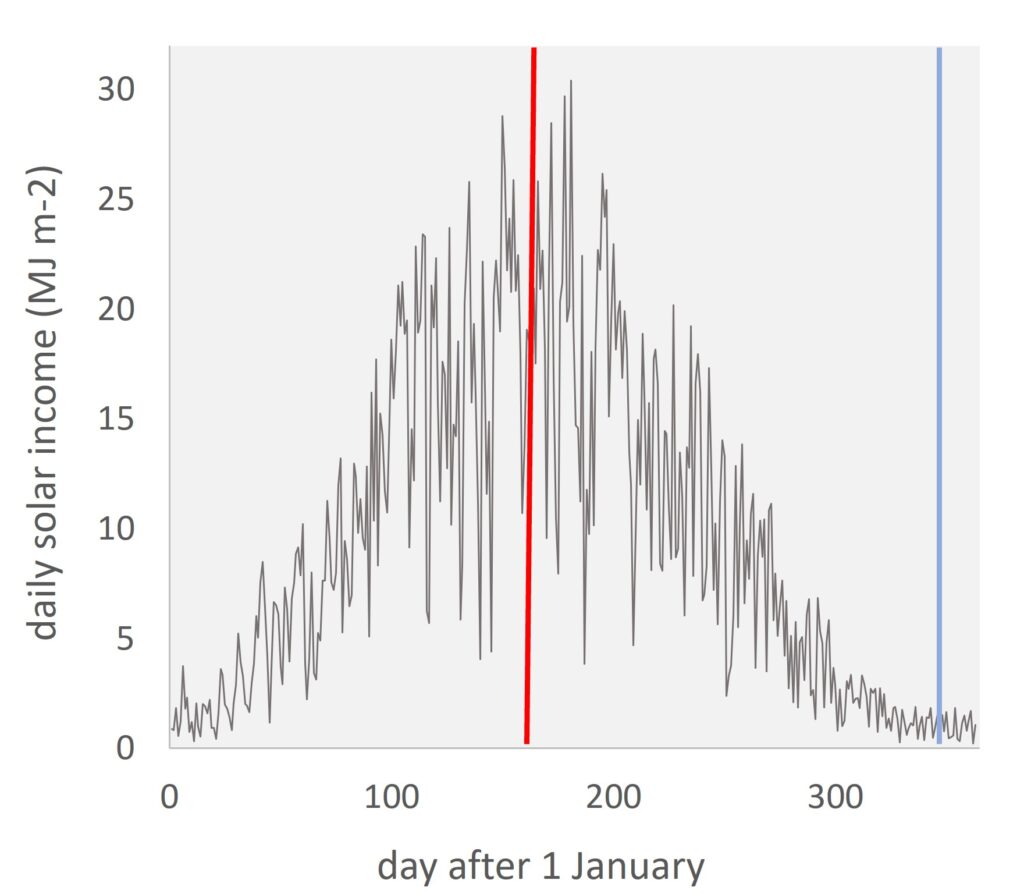

The graph of daily solar radiation received at the earth’s surface in 2021 (Fig. 2) shows the summer peak and winter low, but also the great day to day variation caused by cloud. The average around the winter solstice in December was about one-tenth of that around the summer solstice in June.

Fig. 2 Daily solar radiation received at the earth’s surface, at Kinloss near Inverness, from 1 January to 31 December 2021, vertical lines at the summer (red) and winter solstice (blue) [4].

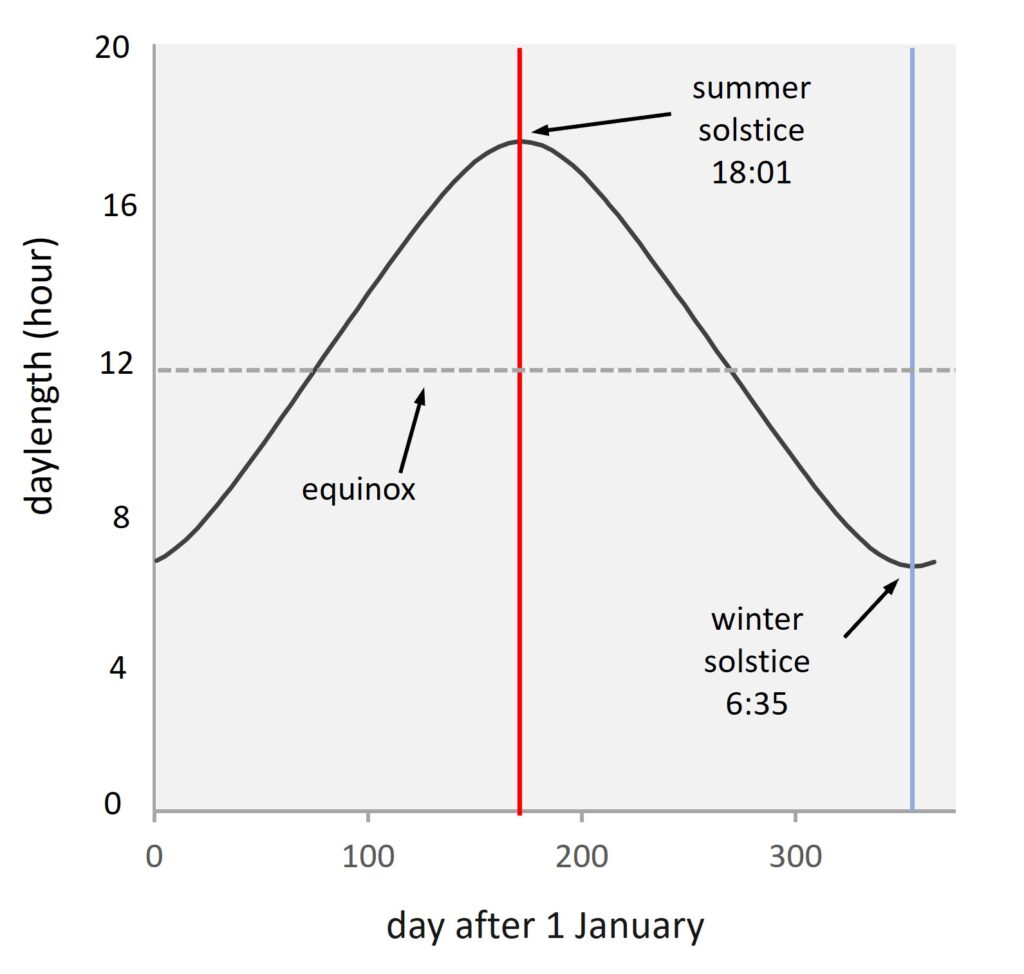

The annual solar variation is linked to both the change in daylength (Fig. 3) and the low elevation of the winter sun. It’s the winter low in Fig. 1 that would make for very cold temperatures in December to February at this latitude if the place was in the middle of continental Europe rather than by the sea.

Fig. 3 Change in daylength through the year from 1 January to 31 December at Inverness, 57.46 N, vertical lines as in Fig. 1, horizontal dashed line drawn at the equinox, hours of daylength at summer and winter solstice indicated [4].

But can the area support tropical rainforest? Not quite (not yet!), but Inverness Botanics lets you feel what it might be like.

The Glasshouses

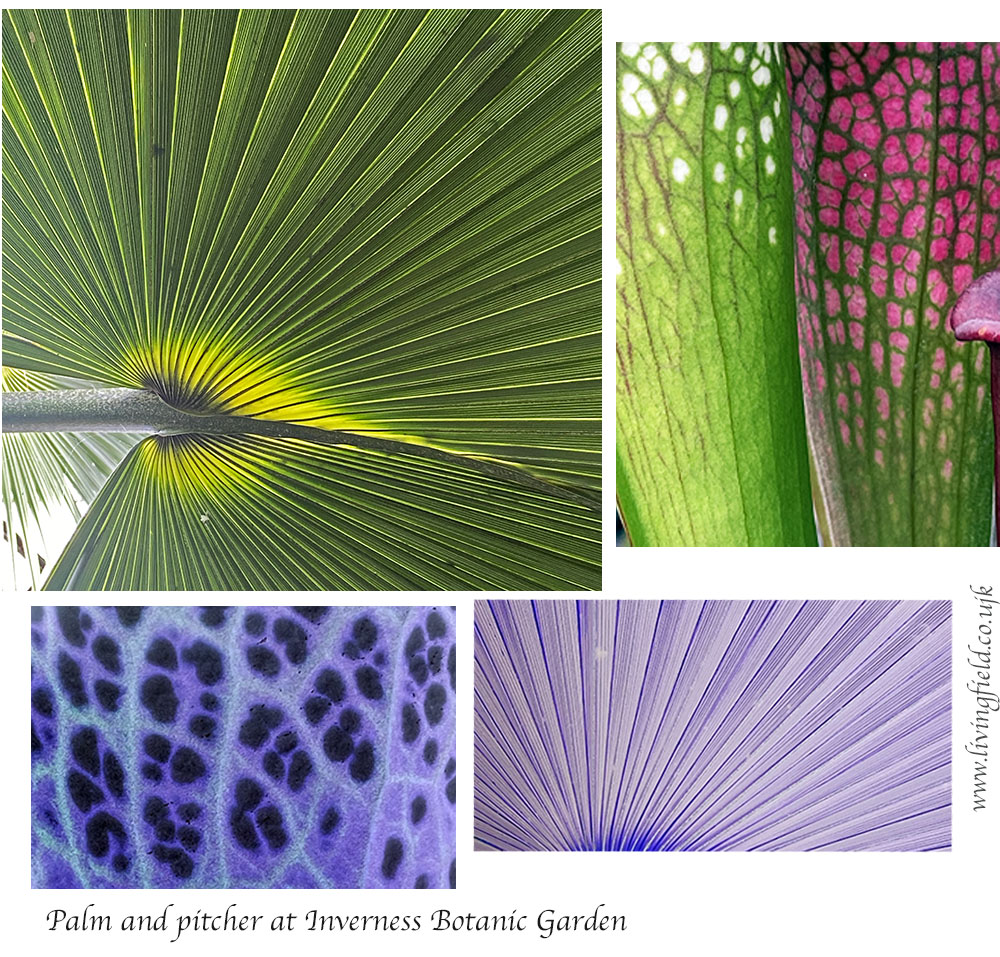

Inverness Botanics houses a diversity of tropical and sub-tropical plants, all viewable from short walkways, some elevated so you can look down at the tops of small palms and plantains. Rock piles, stone walls and big mirrors partition the space making it feel secluded and personal. A few seats and benches give people a chance for quiet contemplation, immersed in the tropical warmth.

The moist tropical section also has several types of epiphyte – plants that grow on on other plants, but are not parasitic, instead taking nutrients from the water falling on them and their host. Tillandsia usneoides, from south and central America, is one of them, forming a hanging mass of stems bearing short thin leaves. It was good to loiter here – brought back memories of tropical rain forest.

Past a bench of pitcher plants and into the cactus house, displaying a stunning range of shape – tall, thin and hairy, round and prickly. You can’t miss Cleistocactus straussii, native to high mountainous regions in Bolivia and Argentina. A note next to the plants says it can withstand temperature down to 10C, and survives the winter with little water. (Couldn’t live in the Highlands then!) Near to it are the prickly orbs of Echinocactus grusonii, from Mexico.

Go out of the glass, find the path and follow the signs to …..

The GROW Project

The Garden’s web pages explain: “…. an opportunity for practical horticulture for adults with a learning disability. GROW stands for Garden-Recycle-Organics-Wildlife …. The GROW Project provides a sympathetic workplace-type environment that uses horticulture therapy to deliver training and work experience ..…”.

This part of the garden was well occupied on the day of our visit in mid-October, families wandering, children looking at things – an easy relaxed atmosphere .The flowering season was over for most species but earlier in the year: “… you will find fruit trees, vegetable plots, wild flowers, bulbs, herb beds, a bug hotel to encourage insect life, and much, much more. For children the wooden bears at the tee pee and Jungle Path are looking forward to welcoming you!”

G.R.O.W. has won formal support from public and private funds, including over £20k in 2021 from the Inverness Common Good Fund to buy around 50 m of raised beds to give people a comfortable working height [5]. The food produced by G.R.O.W is sold on site or else donated to Inverness Foodstuff [6].

Volunteering

Here’s an extract from the Garden’s web pages …

“Our volunteers play a vital part in many aspects of the smooth running of the Gardens. Over the last few years they have spent many hours on the various tasks to assist our gardeners. Inside and outside they help with many horticultural tasks and maintaining our woodwork, paths and glasshouses.”

Follow the links below for more information about becoming a volunteer.

The blog from Marr Communications gives more on the history, activity and aspirations of G.R.O.W and the Botanics [7].

Links

[1] Inverness Botanic Gardens and Cafe Botanics at visitinverness and highlife highland. Quotes in the text are from these web links. The Garden also has a facebook page: search @invernessbotanicgardens

[2] On BBC News, 15 January 2014: Inverness floral hall to be branded as botanic gardens. And more information at Britain Express.

[3] Birse and colleagues, working from Aberdeen in the 1960s, produced three stunning maps of the climate in Scotland: Birse EL. 1971. Assessment of the climatic conditions of Scotland. Soil Survey of Scotland: Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen (now the James Hutton Institute). The first of the maps – on temperature and rainfall – is used here to indicate the relatively mild climate of Inverness compared to much of the surrounding land.

[4] Sources of data: for solar radiation, location Kinloss – Centre for Environmental Data Analysis CEDA; for daylength, location Inverness – Time and Date. Graphs constructed by www.livingfield.co.uk. The Living Field web has several articles on solar radiation and climate, e.g. Solar income.

[5] The Highland Council, 15 December 2021: Huge donations to help project GROW – describes what will be done with funds from the Inverness Common Good Fund and HSBC Bank.

[6] Inverness Foodstuff at Ness Bank Church.

[7] Marr Communications: Growing more than just plants.

Ed: thanks to our correspondent for their note on Inverness Botanics and photos taken during visits in July, October and December 2022, examples of which we use on this page.

[Update: some minor editing and rearrangement of figures on 24 December 2022]