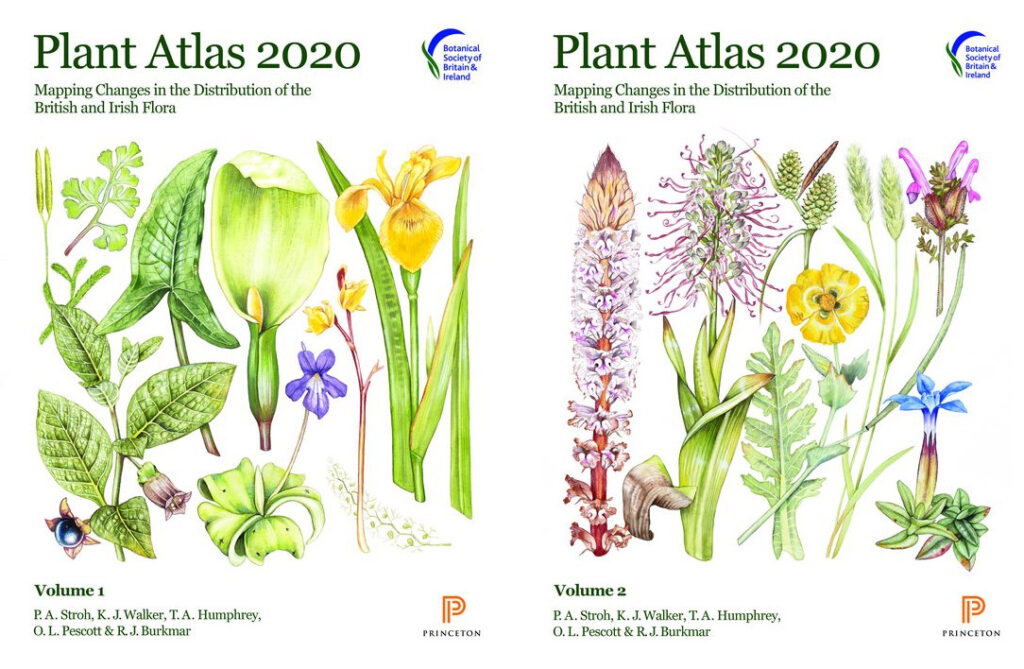

Mapping changes in the distribution of the British and Irish Flora.

Published by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) in 2023

Notes from the Online launch 9 March 2023. Web: plantatlas2020.org

Those of us involved in field survey have long valued the plant atlas produced by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI). The two previous publications, in 1962 and 2002, have been invaluable, and so will the latest version published earlier this year – Plant Atlas 2020.

It took 20 years of field recording and three years of analysis. Thousands of botanists did the surveys, often under the guidance of the county recorders who know their area intimately. In all, they assembled 30 million records, of 3495 species.

Each species is given a general description, then its altitudinal range, phenology (its sequence of development – vegetative, reproductive, seeding), time trend and a distribution map in 10 km squares over the country.

What of the changes? There’s been some gain – but the main conclusions are continued loss of plant biodiversity. For estimate of changes since the 1950s, plants are placed into one of three classes

- native species – of which 53% have declined;

- archaeophytes, that have been here a few hundred years – of which 62% have declined;

- neophytes or recent introductions – of which 58% have increased.

This summary is no surprise to those who have surveyed plants in managed ecosystems across the country.

Why have natives and archaeophytes declined – loss of habitat, destruction or modification of habitat through intensified management, fertiliser application, pollution, erosion, run-off, drainage, and overgrazing; loss of small farms. Not all is bad – some species such as cornflower have increased in occurrence due to the sowing of wildflower seed mixes. But the overall position is that Britain continues to lose plant species and many of the losses are in arable and grass farmland.

Some of the recent plant introductions are doing the opposite – taking advantage of disturbance. Sitka spruce is one – introduced as a forest plantation tree across the country but now spreading through self seeding. It’s all over the place – on the shores of pristine lochs, in marshland, moving over the moor.

Climate is having an effect. ‘Winners’ are southern species that can take advantage of the warming. ‘Losers’ are montane species suffering due to reduced snow cover and dryness.

What can be done? The online launch gave five key actions:

- Protect the best sites.

- Allow more space for nature – reduce the pressure.

- Ensure plants are taken account of in decisions on land use.

- Continued research and monitoring

- Raise the awareness of plants – encourage skills in identifying, understanding and managing.

And it’s true plants are generally overlooked by those who manage the countryside. One of the reasons for starting the Living Field project back in 2001 was to raise awareness of lowland plants and their many contributions to ecosystem function and their uses to people through the ages. We’ll continue …. but the pressures against plant diversity are not waning.

We can look back to the BSBI’s efforts before Plant Atlas 2020 …..

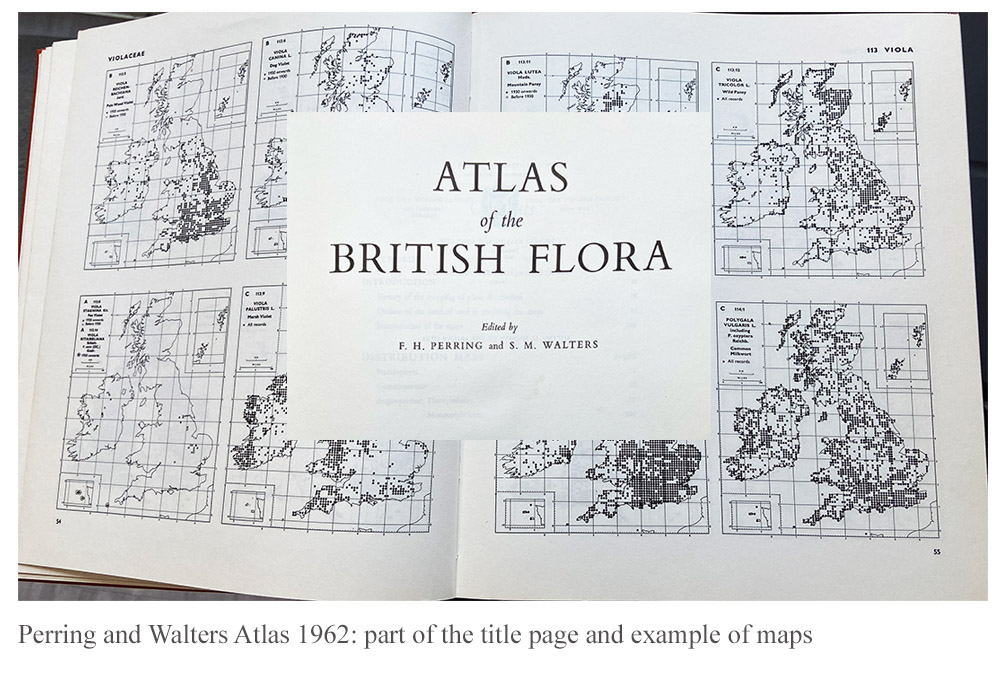

1962 Atlas by Perring and Walters

On joining SCRI, one of the two founder Institutes of the James Hutton, in the 1990s, I found that much of the work was based in crop breeding (potato, soft fruit and barley) and pests (viruses, fungi and insects). Weeds as pests were given less emphasis and money, but arable plants other than crops were still mostly treated as pests. Nevertheless, the Atlas of the British Flora published by the BSBI in 1962, edited by FH Perring and SM Walters, was in the library, originally at the Scottish Plant Breeding Station, which was then at Pentlandfield, Midlothian, before it moved to become part of SCRI in Dundee. The book was bought in July 1962 and cost £3/10. The image above shows a part of the title superimposed on one of the pages showing the distribution maps for the species.

2002 New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora

Gradually during the 1990s the notion was debated that weeds, or as some of us would prefer ….. arable plants, had attributes that were positive for the farmed ecosystem, notably the provision of plant food for beneficial invertebrates such as detritus-feeders, beetles, spiders and pollinators.

In the late 1990s, the research grouping that was to become Agroecology at the James Hutton, began to win research contracts in vegetation dynamics, geneflow and ecological risk assessment. Over several years, the group sampled crops and wild plants in fields from the south coast of England to Ross and Cromarty In Scotland.

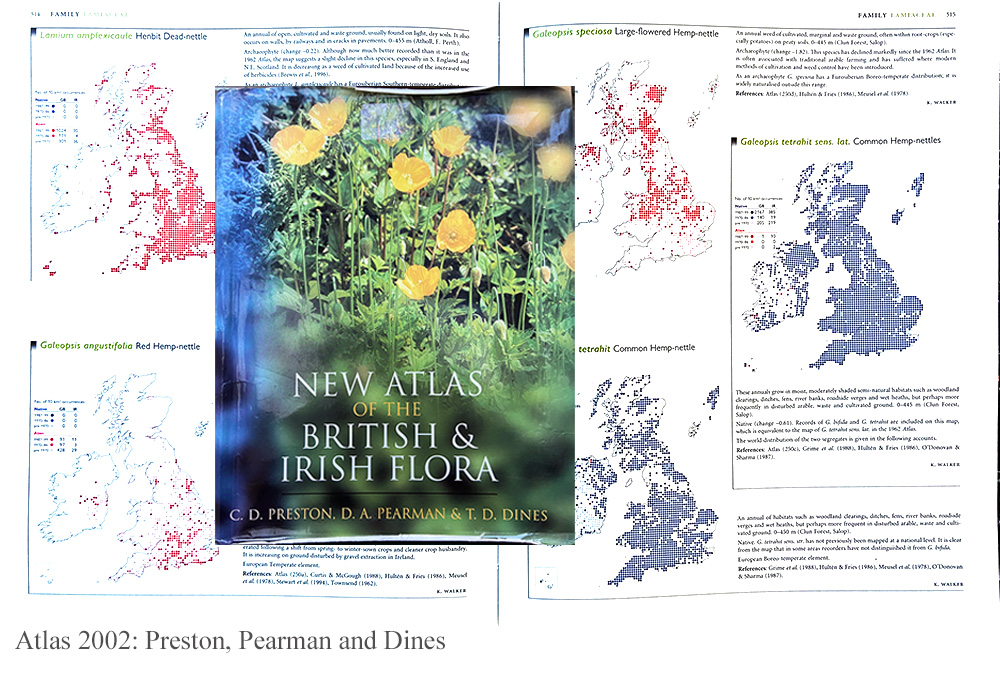

Fortunately for us, the revised version of the 1962 Atlas, named The New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora, edited by CD Preston, DA Pearman and TD Dines, was published in 2002. The cover – in our case very worn from much usage of the book – is shown on a page of maps for several species.

The pages chosen showed distributions of the hemp nettles, of the genus Galeopsis, that occurred widely within cropped fields in the east of Scotland at that time, causing little problem as a weed but providing a base for the invertebrate food web.

Thanks

The making of these Flora takes a massive effort from the main editors and organisers but also the thousands of volunteer botanists who survey and identify the plants throughout the country. The Living Field has already used the online edition to answer questions from our correspondents. It’s a fantastic resource ….. there to use.

Links

The Botanical Society of British and Ireland (BSBI) web site – https://bsbi.org

BSBI Introductory page to Plant Atlas 2020 – https://bsbi.org/plant-atlas-2020

The 2022 Atlas accessible online – https://plantatlas2020.org

Summary Report of the 2020 Atlas.