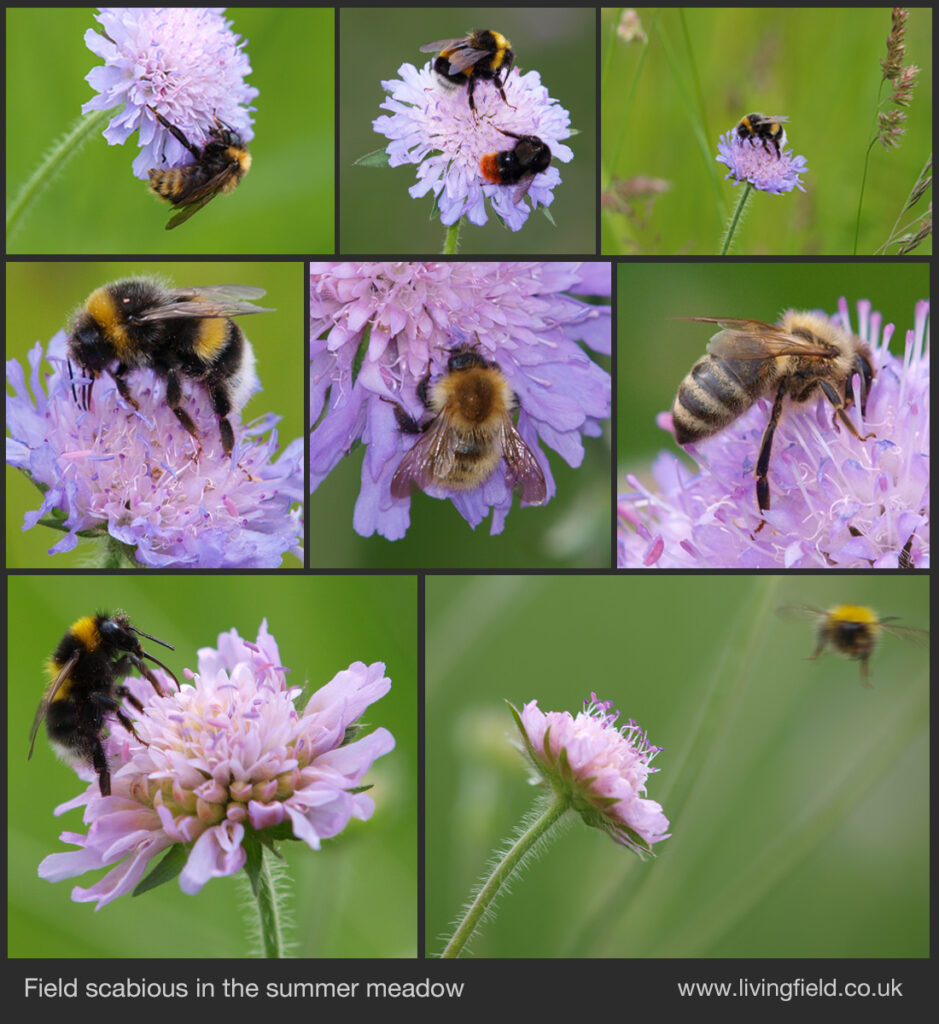

Field scabious flowers in the Living Field garden’s meadow for several months over summer and early autumn.

sustainable croplands

Field scabious flowers in the Living Field garden’s meadow for several months over summer and early autumn.

Want to help stop the widespread decline of bees and other airborne insects? Here are some notes on the Garden’s plants most visited by bumble bees, hive bees, hoverflies and the occasional butterfly. Most of these plants are easy to grow.

One of the main aims of the Living Field garden is to allow native cropland plants some space away from weedkiller treatment and competition with crops. Recent scientific reports have drawn attention to the widespread loss of invertebrate life and insect life in particular. The declines are happening all over the world.

Everyone who owns or manages land can do their bit to support flying insects. Here we show some of the Garden’s plants and plant groups that have offered food and shelter to flower-visitors over the years.

The legumes (family: Fabaceae), just ahead of the Composites, are the single most important group supporting wild flyers. The legumes as a whole offer probably the greatest variety and longest flowering season of all plant groups in the garden. They fix their own nitrogen from the air. All parts of the plant are high in protein.

Sainfoin, the melilots and lucerne were once grown or tried as forage crops in Scotland. The clovers, mainly white and red, are still sown, but the red is more commonly seen in the wild. The bumble bees’ favourite of them all is the blue-flowered, tufted vetch (lower images in the panel) – its strings of flowers produced for months on indeterminate sprawling and clinging stems.

Next are the composites (family : Asteraceae), each flowering head consisting of many individual florets. Not all species are equally visited, but the best here for pollinators are thistles and knapweeds. The great cotton thistle grows like a small tree, supporting large heads several centimetres across, bumble bees often bustling two or three to a head.

The greater and common knapweeds, hemp agrimony and tansy shown above are perennials, whereas the thistles in the garden tend to be biennial – germinating one year, overwintering as a rosette and flowering the next. The weedy perennial creeping thistle is too invasive in the garden’s small space and though it supports insects is discouraged in favour of other thistles.

Of all the species in the garden, field scabious (family: Dipsacaceae) is the one that offers sustenance to flyers for the longest period. A perennial, growing mainly in the meadow, plants put out flower after flower from early summer to late autumn (except in the very dry 2018). If there was one plant that we could grow for the bees, it would be this.

Teasel is a close relative that also grows well here. It self seeds and is mostly biennial. Plants are moved at the rosette stage in autumn or early spring to form clumps that flower in the medicinals bed.

The labiate family (Lamiaceae), including mints, sages, woundworts, deadnettles, hempnettles and basils – are well represented among the medicinals and herbs. They grow in sun, in shade and as occasionals anywhere. The large flowered types such as the herb sage are most frequently visited by the Bombus species, while betony tends to attract more of the smaller carder bees.

The smaller flowered species, such as meadow clary (a perennial n the meadow), fields mints, hempnettle and wild basil are less attractive to larger flying insects but have their own specialist range of inverts.

These are not the only plants that offer food and shelter for flying insects. Among the first in the year are the flowers and leaves on the garden’s native trees and shrubs. Early summer in the hedges, flowers of wild roses offer a welcoming landing platform for grazing hoverflies.

One of the longest flowering species, not shown here in the photographs, is viper’s bugloss Echium vulgare, one of the borage family. (See it at the Bee plants links below.) Borage itself and the comfreys are also well visited.

Populations of bees and other flower-visitors were very badly affected here by the dry 2018. There was little left in flower by the end of August, while in most years the field scabious and viper’s bugloss are still visited in late October.

The coming year’s weather is uncertain as always, but we’ll try to manage the plants to give the longest possible season to the resident insects and spiders. First out will be the willow ….. .

Nearly all the plants referred to here are native species or ones introduced long ago and now naturalised. Very few of the crops grown in the region (and the garden) – barley, wheat, oats, peas – support or need pollinating insects.

Oilseed rape fields provide a crop-based source of food for a few weeks early in the year and field beans also offer high-protein flowers much later. But the main sown crops and leys that could provide the right seasonal habitat – the legume forages and grass-clover mixtures – are rare and mostly long gone.

In the broader landscape therefore, the main source of food for flying insects lies in the broadleaf ‘weed’ species that live in crop fields and disturbed margins – in fact most of those shown in the panels above belong in this category. These arable plants, mostly not injurious to crops, have declined over the last century to the point where many of the plants themselves are now rare. It’s no wonder insects apart from pests are having a hard time in cropland.

The Living Field’s page on Bee plants give further notes and images of the individual species most frequently visited in the garden.

As usual, the plants are grown and tended by Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson with help from the farm.

The photographs of the insects on field scabious were taken by Linda Ford on an ideal summer day a few years ago, the others by Geoff Squire. Colleagues from the farm cut the Living Field meadow once a year and trim the hedges in sequence every few years to allow flowering and fruiting (e.g. for roses, willow, hazel).

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com

Flower head of chicory (Cichorium intybus) with four insects, the small one perhaps grazing pollen, the others going for the rich centre and trampling the (male) pollen bearing anthers held bifurcating on thin blue-lined tubes and curling inwards like muscle-flexing stick-men

… on an organic farm, East Lothian, 15 August 2014 (Image by Squire).