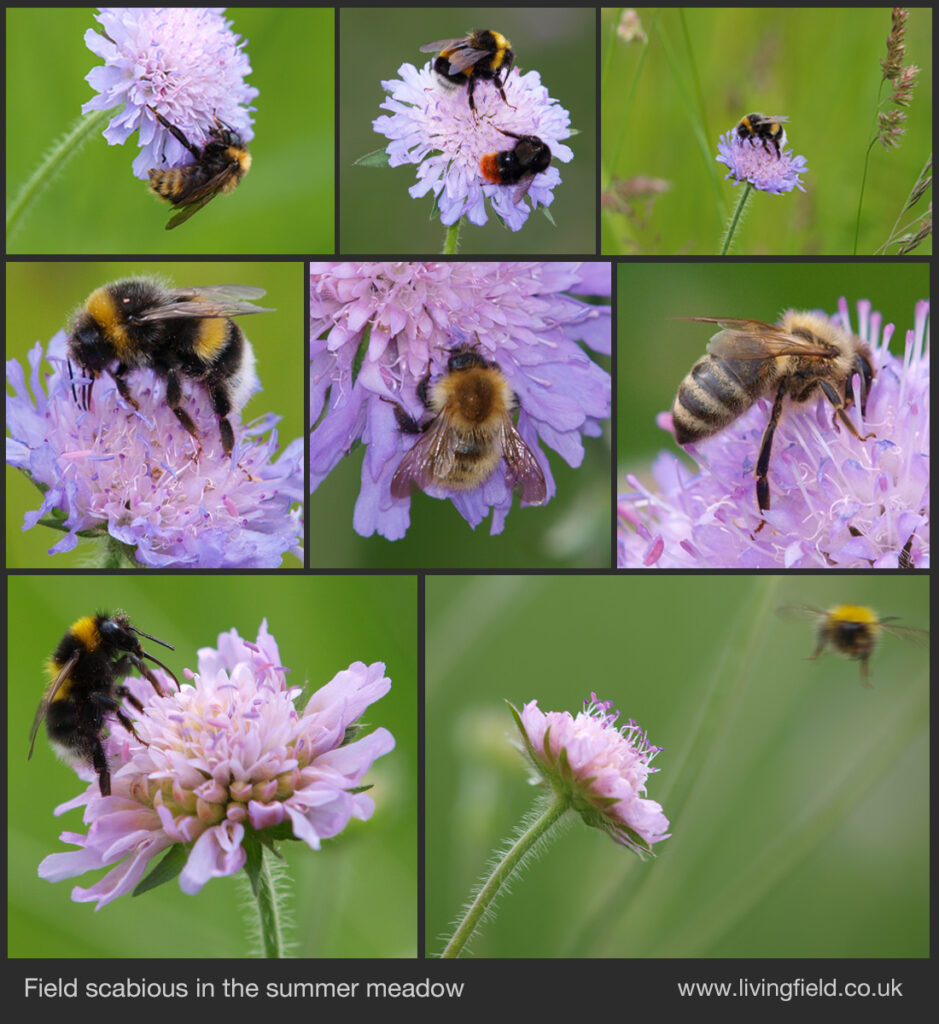

Field scabious flowers in the Living Field garden’s meadow for several months over summer and early autumn.

sustainable croplands

Field scabious flowers in the Living Field garden’s meadow for several months over summer and early autumn.

Mixtures sown for hay or grazing in the 1800s. Grass, legumes and other broadleaf plants selected for their ablity to live together. Many of the plants grown then coexisting now in the Living Field garden. Lessons for grass rediversification today. One of a series of articles on crop-grass diversification.

The run of bad weather, crop failure and hunger of the late 1600s, sometimes called ‘the ill years’, was one of the factors that led to a period of agricultural improvement from the early 1700s to the late 1800s. The improvements raised and to a degree stabilised food production. One of the most important developments was the design and trialling of species-rich plant mixtures for hay and grazing.

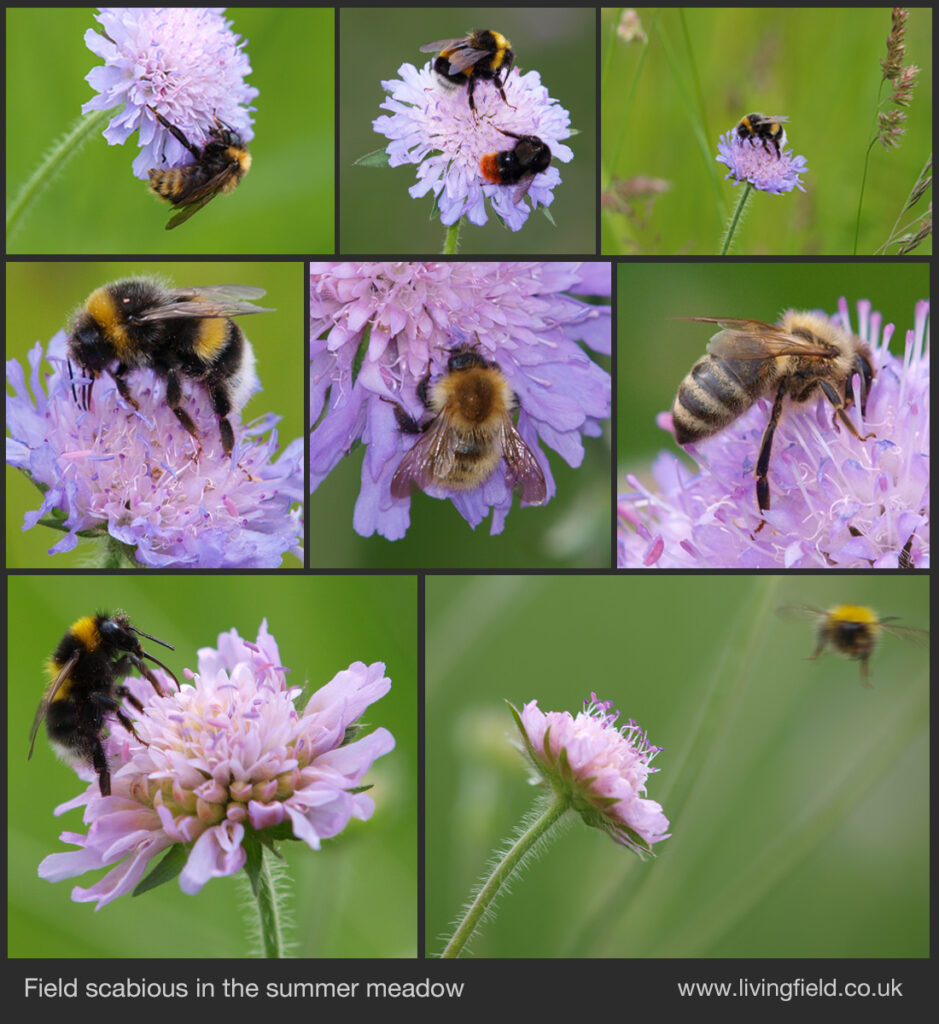

Early accounts of ‘grass’ mixtures by agriculturalists, notably Stephens, Elliot and Findlay, are valuable to us today because they gave weights of the seed of each plant species that made up the mix [1]. Though weight of sown seed does not translate directly into mass of the species in the field, it is the only measure handed down to us by which the diversity of those old mixes can be quantified and compared with today’s commercial seed mixtures.

Why is this important? Over the last 150 years, crop-grass agriculture has become less diverse, more dominated by a few grass species and in the process losing many ecological functions. Plans to re-diversify could learn from past practice.

The hay and grazing mixtures from this period are summarised in a related web article [1] as circular diagrams, the inner ring showing the proportions of grass (blue-green), nitrogen-fixing legume (red) and, when included, other broadleaf plants (orange-brown), while the outer ring shows the proportions of individual species. The diagrams below show the rise in complexity of the mixtures from one-year-hay (1) to two-year grazing (2) and permanent pasture (3, 4).

The main feature of those mixes – though rarely seen today in commercial grass fields – is the presence of several legumes species and sometimes broadleaf plants other than legumes. The role of the legumes is to fix nitrogen gas from the air and so enrich the soil for the grass species at a time when mineral fertiliser was not widely available. The other broadleaf species were included to fill ecological gaps (functions and processes) that could not be provided by the grasses or legumes.

The meadow in the Living Field garden [2] was sown back in 2004. In the first few years, the most visible plants were those that grew quickly and flowered in the first or second year. These annuals and biennials were soon ousted by perennials, some that had been sown and others that came in. After 5 or 6 years the meadow was populated by a diverse group of perennials.

The meadow has been lightly managed – cut once a year, usually in September. Yet many of the plant species that were part of the 1800s mixtures appear naturally able to coexist in the meadow and surrounding patches.

The typical legumes in early grass mixtures were clovers, the red and white species but also alsike and several others. Red Trifolium pratense was thought best for one year’s hay because it was fast growing but short lived, while white Trifolium repens persisted much longer and was suited to pasture. Both have lived in the meadow for at least a decade. Alsike Trifolium hybridum was grown as part of a legume collection a few years ago but has not remained.

Other legumes in sown mixtures from the 1800s included the bird’s-foot trefoils, mainly Lotus corniculatus which is as common in the meadow as white clover, and kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria which persists as only a few plants here and there among the grasses and sometimes in the medicinals bed.

The meadow has other legume species, of the genus Vicia, that were not generally favoured in earlier mixtures because they have tendrils and so tend to twine among and drag down the grasses and other plants.

Two common tendril-bearing species recur in the meadow each year – common vetch Vicia sativa which generally keeps to itself and hairy tare Vicia hirsuta which can become a serious weed (as this year) smothering other plants. A third one of this type, tufted vetch Vicia cracca tends to move around unkempt patches rather than live in the meadow.

The images in the legume panel above show (top left, clockwise) white clover among grass and plantain, common vetch, kidney vetch and red clover with bird’s-foot trefoil (yellow flowers).

It may come as a surprise today to learn that plants other than grasses and legumes were purposely sown in fields as part of mixtures for hay and pasture. Of those reported from the 1700s and 1800s, the commonest in the meadow itself are yarrow Achillea millefolium and ribwort plantain Plantago lanceolata.

Two others have appeared in grassy areas – chicory and burnet. Chicory Cichorium intybus was first planted in the medicinals bed, but has spread and now lives among grasses such as yorkshire fog and cocksfoot. Its main role in the 1800s mixtures was to break through soil pans that formed at 10-20 cm depth due to the shallow ploughing that was typical of the time.

A few plants of burnet Sanguisorba minor were noted a some years ago, and like chichory have persisted for years among competitive grass species. We do not know where the burnet came from.

The images above show (top left, c’wise) burnet and ribwort plantain among grasses, yarrow leaf, chicory plant with blue flower inset, burnet leaves and red stems. and finally ribwort plantain with flower inset.

They might ‘all look the same’ in leaf, but their basic floral structure recurs in many forms to give great diversity among our common grass species. Many of the early sown mixtures included timothy-grass Phleum pratense, cocksfoot Dactylis glomerata, crested dog’s-tail Cynosurus cristatus, several fescues (Festuca species) and tall meadow-grasses (Poa species), all of which are present in the meadow.

Two other pasture grasses are common in the garden – sweet vernal-grass Anthoxanthum odoratum and yorkshire fog Holcus lanatus which become established wherever the ground is left untilled for a few years.

The grass panel above shows (top left, c’wise) mainly yorkshire fog growing among wild carrot, flowering heads of sweet vernal and timothy and (from the early years) fescue and crested dog’s-tail among ox-eye daisy.

The 1800s mixtures were designed to give a balanced diet for livestock and to ensure fresh plant tissue was present for a long as possible during the year. They mixed species to ensure that each came to prime leaf or seed at different times. For hay, the progression of floral or reproductive structures was important, for pasture the blend of leafy parts.

The meadow in the Living Field garden also harbours other plants sown specifically for wildlife, including field scabious, perhaps the favourite of the pollinating insects, ox-eye daisy and lady’s bedstraw. At one time wild carrot lived in the meadow (top left in the grass panel above) but now prefers grassy margins next to paths. Even with these additional species, the meadow complex retains many of the species sown for hay and pasture from the 1700s to the early 1900s.

The secret of sustaining the meadow is to keep soil fertility low by not fertilising and ground cover high by growing many species that quickly react to fill any gaps. No one species dominates and noxious weeds are given little chance to enter.

[1] The original sources, mainly Wight (late 1700s), Stephens (1841 onwards), Elliot (1898 onwards) and Findlay (1925) are given in this companion article: Grass mix diversity a century past on the curvedflatlands web site.

[2] The origin, main species and management of the meadow are described on this web site at Garden/Meadow and Garden/The_making. The drone image below from early 2019 shows the location of the meadow (covering about 200 square metres), see also : Living Field garden from the air.

The Living Field team has maintained very high diversity per unit area here for almost 15 years.

Contacts: this article geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk; meadow management gladys.wright@hutton.ac.uk.

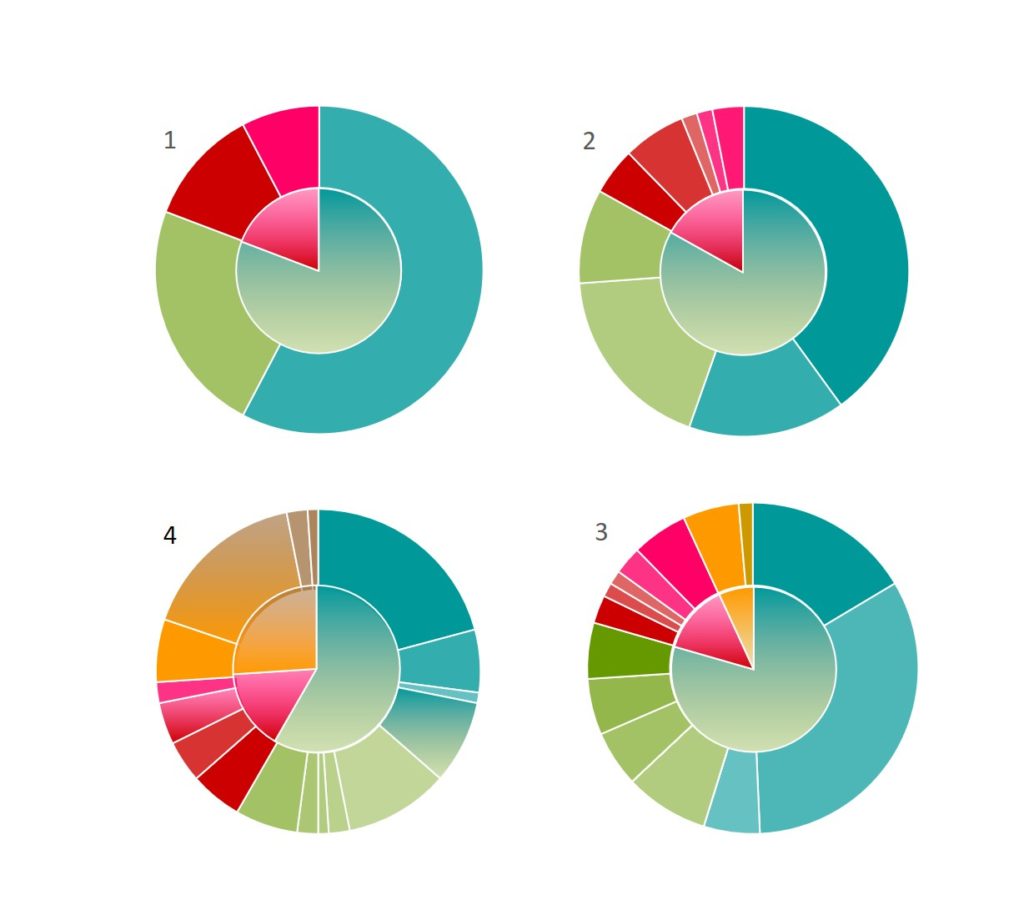

The Living Field Garden was looking good at Open Farm Sunday on 11 June this year. Despite wet weather, we had over 1000 visitors.

More on the Open Farm exhibits appears at the Hutton Institute’s LEAF web pages. Here we look at some of this year’s plants.

The hedges are thick with leaf, the hawthorn now filling its haws, the elder and the wild rose still in full flower. Water forget-me-not and wild iris are flowering in the wet ditch, while field scabious, comfrey and viper’s bugloss are offering plenty for the several species of bumble bees that live in and around the garden.

The three local species in the images above all reside in their own habitats, but are within a few seconds of hoverfly flight to the exotic maize in the arable plot. Maize originated as a crop in the Americas and was unknown in the country before the last few hundred years.

This proximity of the wild and the cultivated is one of the recurring features of the garden. The images above contrast the cropped area of the east garden with the perennial meadow and hedge plants. The field scabious in the meadow will keep the bees well supplied until late September at least.

Through the gate, the west garden’s raised beds are filled this year with vegetables and herbs. There are various cabbages and spinaches, parsley, thyme and dill, companion plantings and intercrops, to name a few, and all are intended to show the very different concentrations of minerals that these plants take from the soil and accumulate in their tops.

The background and results of this study, which is based on research at the Institute, will be covered in a future Living Field post.

We’ve been constructing various small places for insects and spiders since the garden began, but this year, the idea of a more permanent residents block was made real just before Open Farm Sunday. First stack your pallets, add a roof of turf and fill the spaces with small bespoke homes for our creepy friends.

Old logs and fence posts, with holes drilled in the ends, pine cones, garden canes, bricks with holes through, tubes, sticks, bits of rotting wood – all make ideal residences.

The garden made a return this year as the base for many activities at Open Farm. The cabins hosted exhibits on greenhouse gas emissions and nitrogen fixing legumes. The east garden, as you go in through the gate by the cabins, had a soil pit, cereal-legume intercropping, pest traps and the urban bug house shown above, while the west section displayed heathy vegetables, soil bacteria, our friends from Dundee Astronomical Society and Tina Scopa running a workshop on wild plant ‘pressing’.

The garden was maintained by the usual crew: Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson on the arable plots and raised beds; Paul Heffel from the farm kept the hedges in trim and cultivated the soil where required; Geoff Squire arranged the medicinals and dyes and kept an eye on various rarities and curiosities.

Gill and Lauren Banks, with help from the farm, constructed Creepy Towers, for which the ‘chimney’ was crafted by Dave Roberts and the plaque by visiting student Camille Rousset.

There is no formal funding for maintaining the garden – it happens through commitment and hard work, often out of hours.

Contact for the garden: gladys.wright@hutton.ac.uk

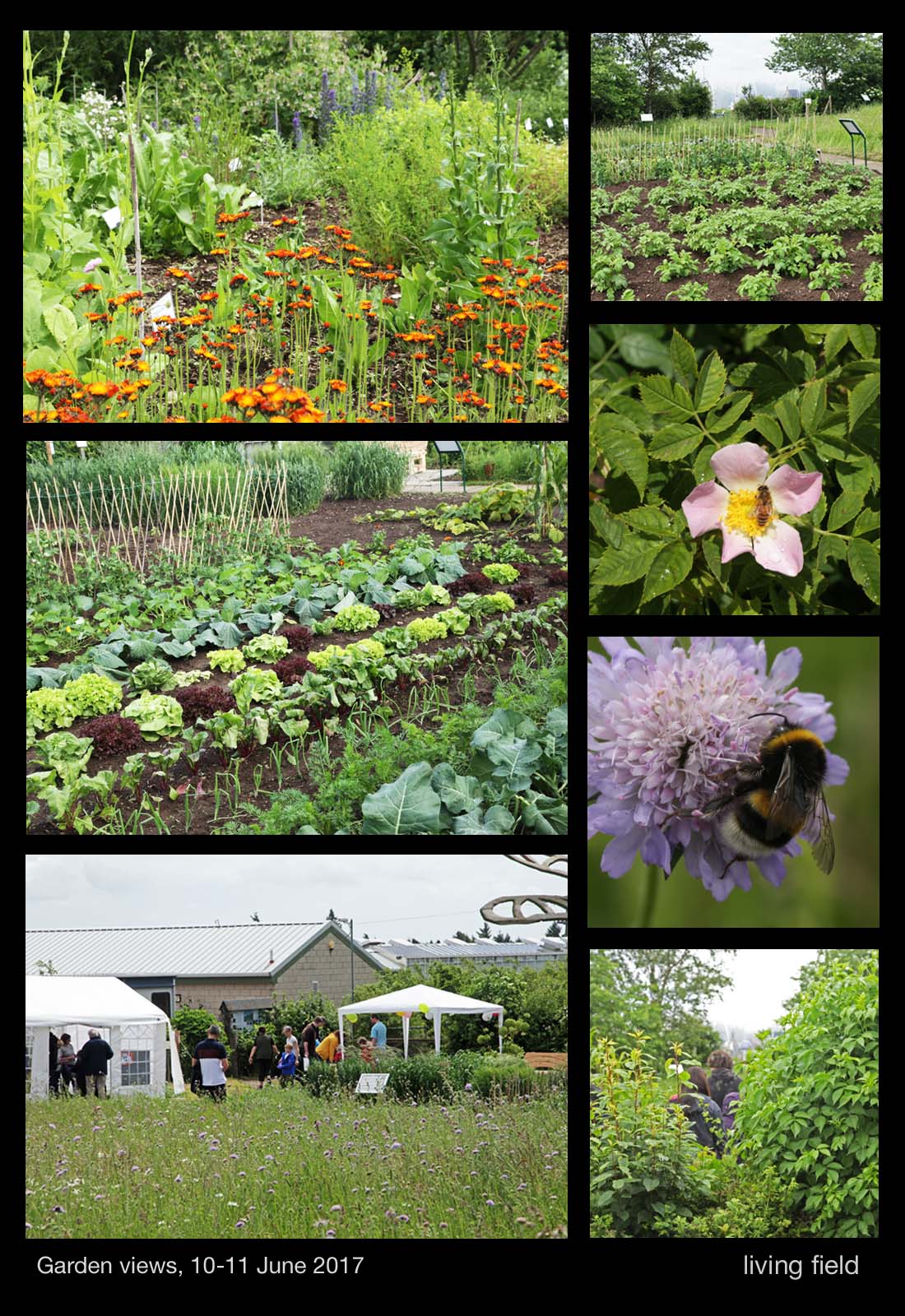

In 2013, we looked for the plants in the Living Field garden that were most attractive to bumble bees and hive bees, from the first flowers in late March, to the time of the first heavy frost in October. Most visitors were bumble bees of the commoner species, but occasionally hive bees foraged around.

We did not grow plants for the particular purpose of feeding bees, yet three areas were particularly active. One was the 10 year old meadow, where field scabious was the favourite; another was the legume collection set up in the west garden; and the third was a piece of rough ground in transition from a sown, annual cornfield to a more perennial community and containing tufted vetch and viper’s bugloss.

By mid summer, many of the bumble bees looked battered and ragged, hardly enough wing left to fly, the result of repeatedly navigating the tangle of vegetation. It’s in a bee’s nature to work itself to death for the hive, eventually falling to the ground or hanging under a flower head. We did not look for nests of the bumble bees to see how many were inside the garden; not did we observe the directions from which the bees entered and left, but that could be something to do in 2014.

Photographs and notes on these and other plants and bees can be viewed at The Garden / Bee plants. All species, including first-year plants of the two melilots, should be around in 2014. (The melilots died after flowering in 2013.) Several plants in the medicinals bed should flower well this year, labiates such as betony, and borages and foxgloves.

[Update 10 September 2014]