By Kit Martin [1]

I think moths are amazing. I do not pretend to be able to identify many of them (and I think there are 2500 species in the UK) but I’ve been fascinated by these elusive, sometimes clumsy, hugely varied and often beautiful creatures of the shadows for a long time. These night-shift (and day flying) pollinators are crucial as food for birds and bats as well as having an intrinsic value just for being moths.

I am working on a photography and printmaking project about moths that in part led on from my FRAY exhibition in 2019 looking at pollinators and wildflowers [2]. It has also been shaped by the fascinating and incredibly talented Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) who is one of the earliest European naturalists to observe insects directly and saw that caterpillars became butterflies and moths, at a time when Aristotle’s ‘spontaneous generation’ theory was still believed.

Maria was also an exceptional artist and the first to include the whole life cycle, including the larval food plant, in her exquisite paintings [3]. Moths were known as Owlbirds in Maria’s time, as they appeared at night and flew. Butterflies were Summerbirds as they were thought to appear from elsewhere in summer.

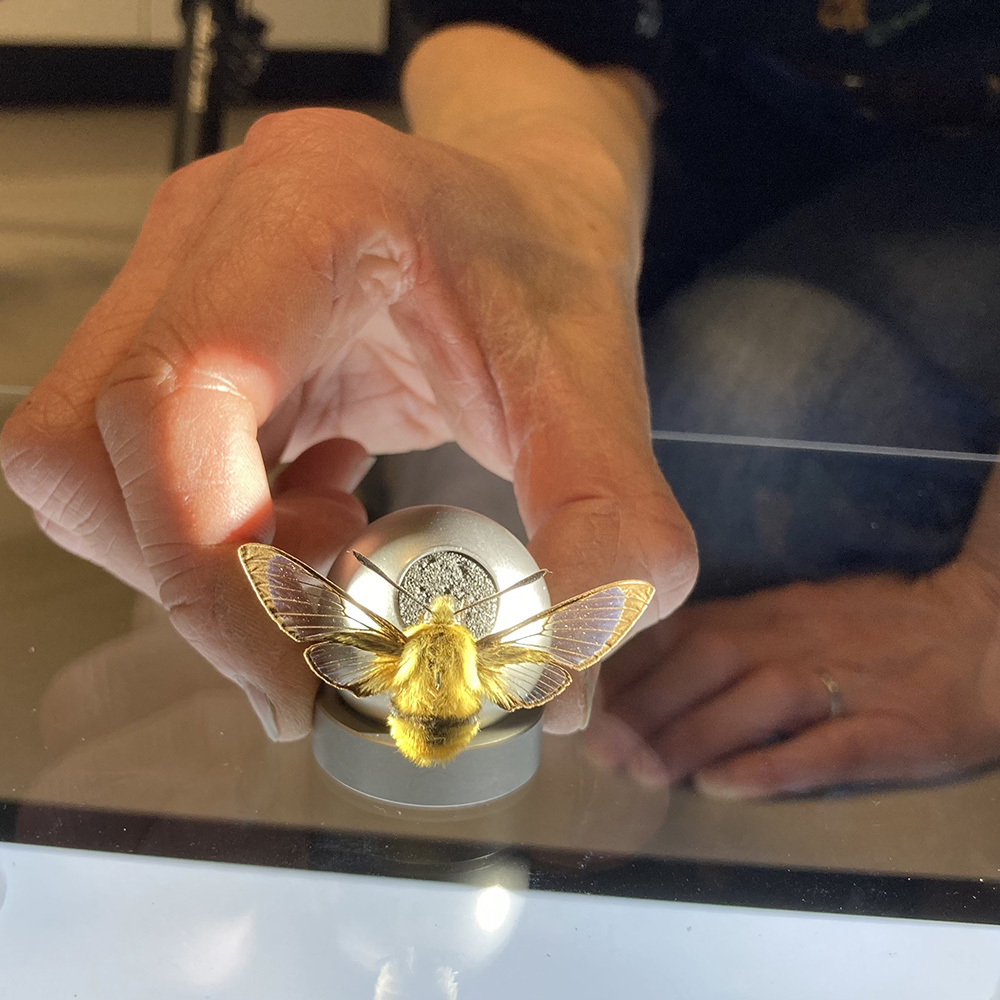

I am working with assistant Curator Ashleigh Whiffen in National Museum of Scotland’s entomology stores [4] where I have kindly been given access to some of the moths in the collection to take photographs. I am also tracking down Trefor Woodford’s collection held by JHI with the aim to photograph some of these moths.

The project will develop over the coming months and I hope to link in some way with the Angus Moth Project [5] and learn from the experts in Dundee Naturalists Society [6], which I joined last year (and am dismayed I hadn’t found them sooner!). I look forward to Moth Night, 19-21 May [7] and learning more about these wonderful scaly winged creatures as I make new work.

Links

[1] Web site: Kit Martin Photography

[2] Kit’s previous article on the Living Field web: Cyanotypes by Kit Martin

[3] On MSM: at the Natural History Museum – Maria Sibylla Merian: metamorphosis unmasked by art and science; and at Botanical Art and Artists – About Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717).

[4] National Museum of Scotland Entomology Collection

[5] Angus Moth Project: 2016 blog from Scottish Museum’s Federation The Moths of McManus

[6] Dundee Naturalists Society

[7] Moth Night

Ed: many thanks to Kit for sharing her interests in moths and we look forward to hearing and seeing about her photography and natural history.