The Living Field Garden was looking good at Open Farm Sunday on 11 June this year. Despite wet weather, we had over 1000 visitors.

More on the Open Farm exhibits appears at the Hutton Institute’s LEAF web pages. Here we look at some of this year’s plants.

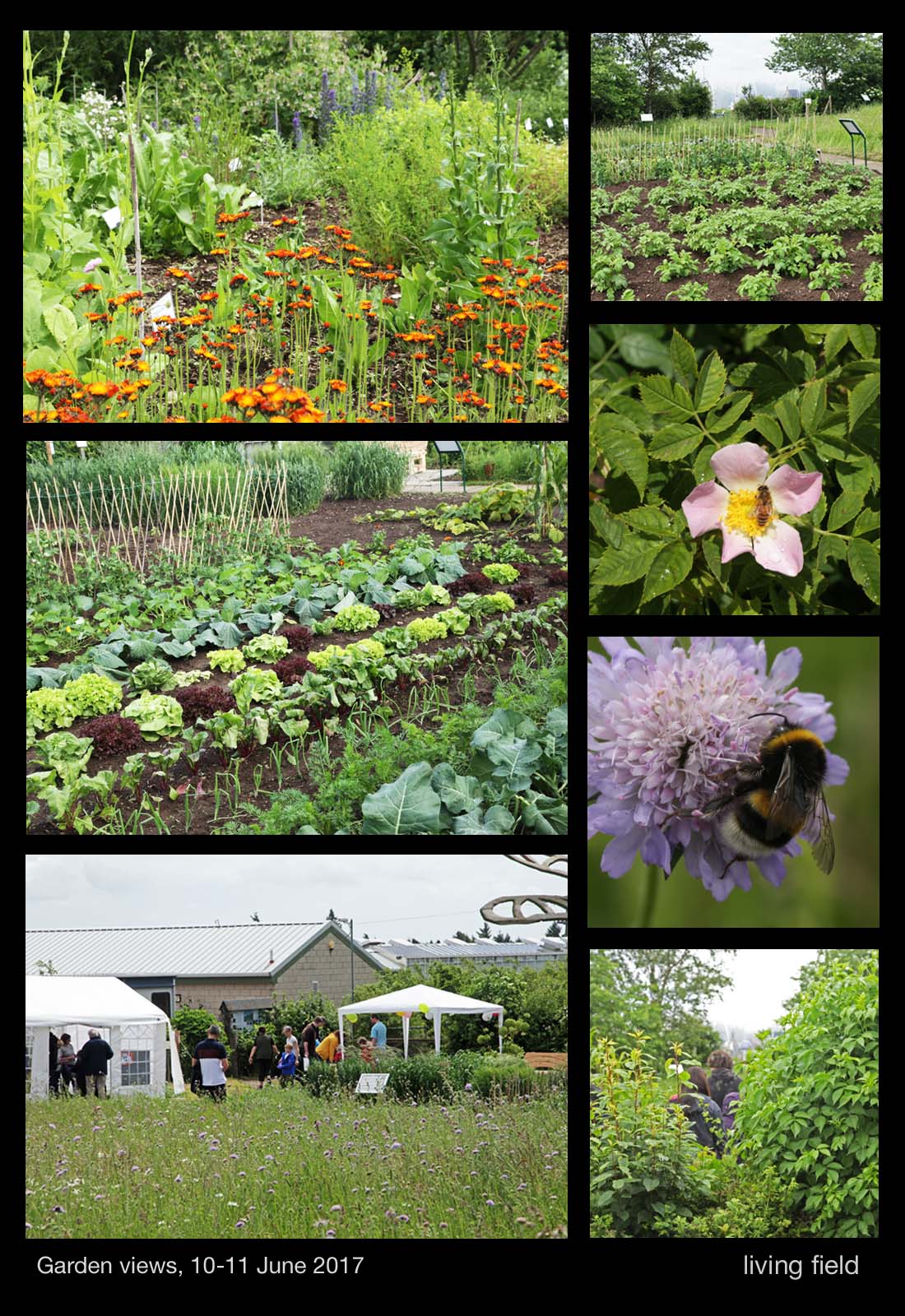

The hedges are thick with leaf, the hawthorn now filling its haws, the elder and the wild rose still in full flower. Water forget-me-not and wild iris are flowering in the wet ditch, while field scabious, comfrey and viper’s bugloss are offering plenty for the several species of bumble bees that live in and around the garden.

The east garden’s perennial and arable beds

The three local species in the images above all reside in their own habitats, but are within a few seconds of hoverfly flight to the exotic maize in the arable plot. Maize originated as a crop in the Americas and was unknown in the country before the last few hundred years.

This proximity of the wild and the cultivated is one of the recurring features of the garden. The images above contrast the cropped area of the east garden with the perennial meadow and hedge plants. The field scabious in the meadow will keep the bees well supplied until late September at least.

Raised beds of the west garden

Through the gate, the west garden’s raised beds are filled this year with vegetables and herbs. There are various cabbages and spinaches, parsley, thyme and dill, companion plantings and intercrops, to name a few, and all are intended to show the very different concentrations of minerals that these plants take from the soil and accumulate in their tops.

The background and results of this study, which is based on research at the Institute, will be covered in a future Living Field post.

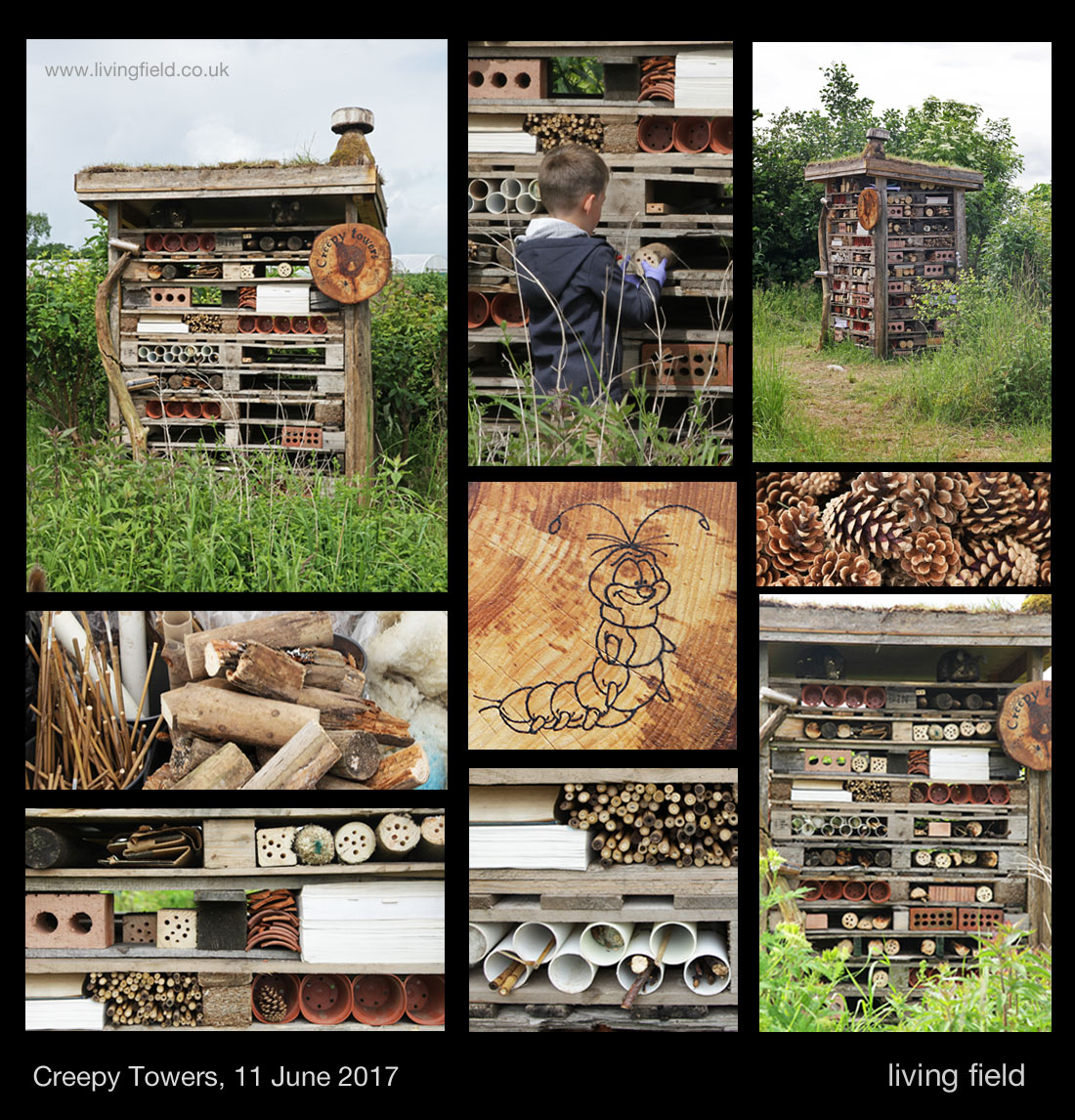

Creepy towers

We’ve been constructing various small places for insects and spiders since the garden began, but this year, the idea of a more permanent residents block was made real just before Open Farm Sunday. First stack your pallets, add a roof of turf and fill the spaces with small bespoke homes for our creepy friends.

Old logs and fence posts, with holes drilled in the ends, pine cones, garden canes, bricks with holes through, tubes, sticks, bits of rotting wood – all make ideal residences.

Exhibits at Open Farm Sunday 11 June 2017

The garden made a return this year as the base for many activities at Open Farm. The cabins hosted exhibits on greenhouse gas emissions and nitrogen fixing legumes. The east garden, as you go in through the gate by the cabins, had a soil pit, cereal-legume intercropping, pest traps and the urban bug house shown above, while the west section displayed heathy vegetables, soil bacteria, our friends from Dundee Astronomical Society and Tina Scopa running a workshop on wild plant ‘pressing’.

The garden was maintained by the usual crew: Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson on the arable plots and raised beds; Paul Heffel from the farm kept the hedges in trim and cultivated the soil where required; Geoff Squire arranged the medicinals and dyes and kept an eye on various rarities and curiosities.

Gill and Lauren Banks, with help from the farm, constructed Creepy Towers, for which the ‘chimney’ was crafted by Dave Roberts and the plaque by visiting student Camille Rousset.

There is no formal funding for maintaining the garden – it happens through commitment and hard work, often out of hours.

Contact for the garden: gladys.wright@hutton.ac.uk