One of the dark materials … a medicinal for a range of ailments … tubers found at archaeological sites suggesting it was eaten … flowers open in the sun … storage in root tubers … dispersal by bulbils …

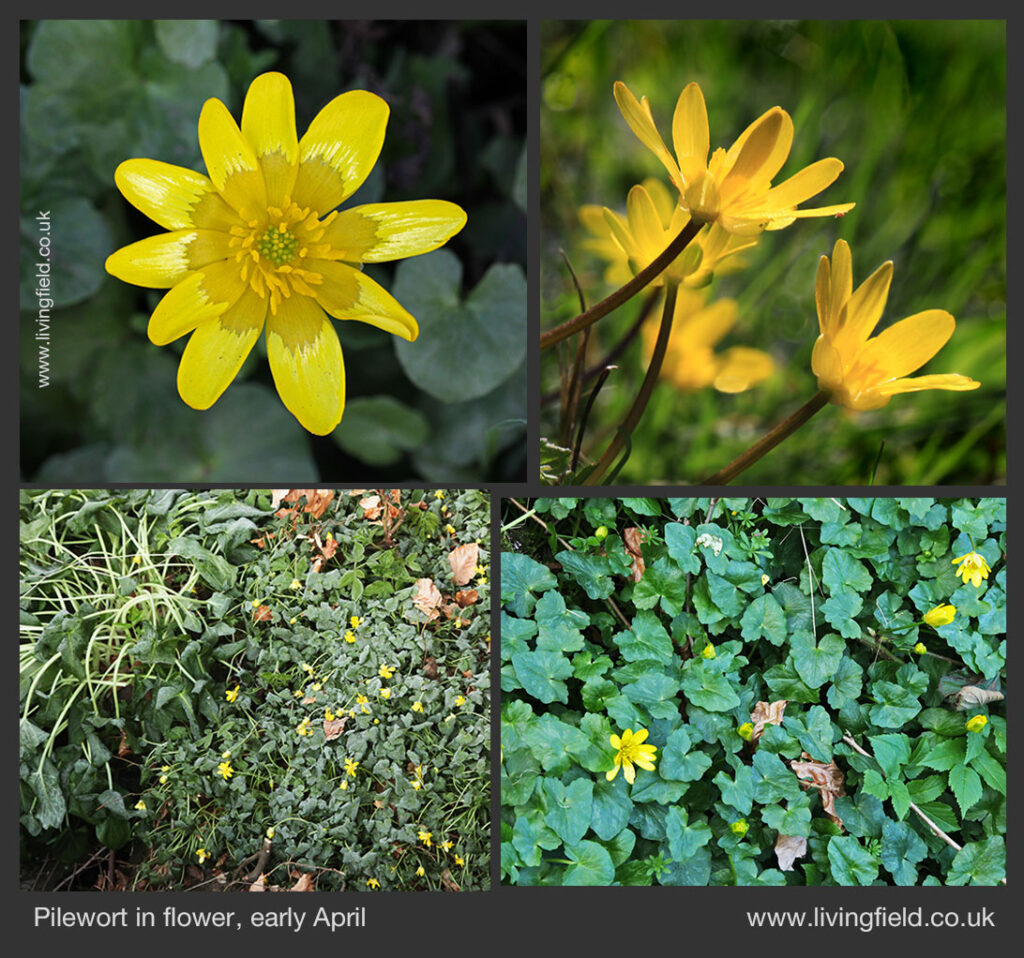

Madwort, mugwort, sneezewort, spearwort – worts apiece. But among the earliest to show itself is the pilewort or lesser celandine Ranunculus ficaria: first the deep green leaves, then the buds and soon the bright yellow buttercup flowers.

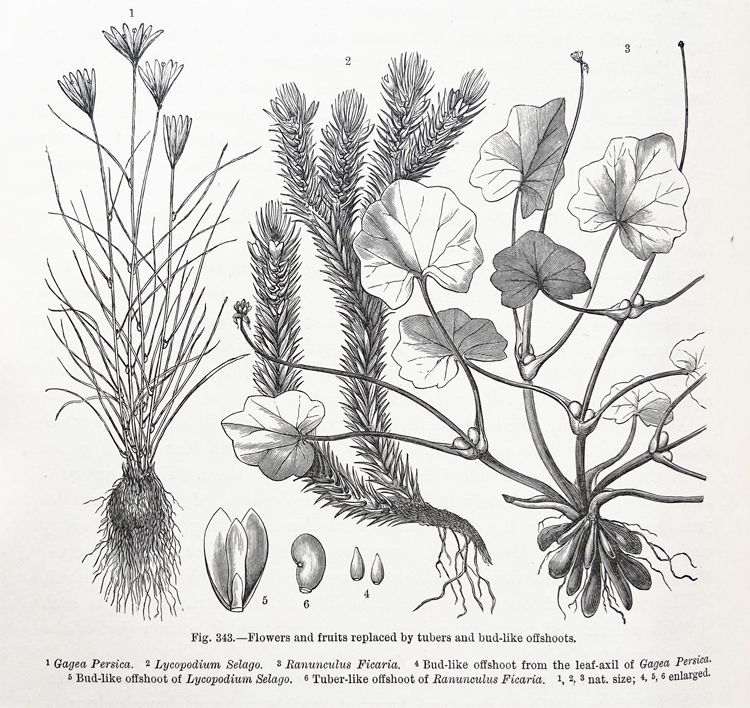

Its ‘business end’ lies in the dark, just below the soil surface. The foliage has gone by summer, but a collection of small root tubers holds the plant’s stores until next spring.

Prehistory – food?

The tubers, usually charred remains, have been found preserved at a range of archaeological sites throughout Europe, extending back to the Mesolithic [1], for example at mesolithic Staosnaig on Colonsay [2] and the Iron Age period at Howe Broch, Orkney [3]. The implication is that the tubers were used as food. Archaeobotanists working on the middle Bronze age in Sweden ‘considered that the tubers had been roasted and eaten like popcorn’ [3]. There are also records of the leaves being eaten.

Most plants in the buttercup family, Ranunculaceae, are poisonous and there are reports that Pilewort has poisoned cattle and sheep [4]. It is difficult to find definitive, recent evidence that it can or cannot be safely eaten by humans, though Long [4] cites Cornevin’s 1887 book that the plant “is not poisonous when young, as in Germany the first shoots are eaten as a salad, but that it becomes so later … “. Other records [1] suggest roots of various species among the Ranunculaceae, which includes plants much more poisonous than pilewort, have been eaten safely when cooked. Given the uncertainties, it would be wise not to try it!

Remedy for a common complaint

The pilewort, also called figwort, is claimed as cure for haemorrhoids, known colloquially as piles or figs. Grigson [5], quotes Gerard’s (1597) observation that the piles “when often bathed with the juice mixed with wine, or with the sick man’s urine, are drawne togither and dried up, and the paine quite taken away”.

Grieve [6] writes that the plant is “used externally as an ointment, made from the bruised herb with fresh lard, applied locally night and morning, or in the form of poultices, fomentations, or in suppositories.” The hanging tubers are also said to offer a physical resemblance to the complaint.

Habitat and reproduction

Plants seem to thrive best in locations that are partly shaded, where sunlight filters through to them in the morning. They sometimes form a near-complete cover, but in nutrient rich places, other plants, such as cleavers and ground elder, will soon grow taller and shade them. In some years, they suffer repeated frosts, from which they recover in a few hours. After a very cold mid-April night, the pilewort in the photograph above (lower left) looked fine by mid-morning while Arum maculatum nearby still displayed frost-damaged, hanging, curved leaf stalks.

The plant has a further interesting feature in the bubils formed in leaf axils. Kerner, in the 1894 translation of his Natural History of Plants [7] reported that when growing in sunny sites, the flowers were visited by pollen-eating beetles, flies and bees that pollinated the flowers, leading to seed formation. But when in deep shade, pollination was less successful, seeds were few and the plants responded by producing “little bulbous bodies in the axils of their upper foliage leaves”, which on becoming detached when the plant withered, were dispersed and gave rise to new plants.

Today the difference reported by Kerner is considered genetic, those plants reproducing mostly by seed and those mostly by vegetative bulbils being classed as different subspecies [8].

Pilewort grows in various places in the Living Field garden. This time of year, it will be flowering beneath cut hedges.

Sources | references

[1] The Sheffield Archaeobotany site: Charles, M., Crowther, A., Ertug, F., Herbig, C., Jones, G., Kutterer, J., Longford, C., Madella, M., Maier, U., Out, W., Pessin, H., Zurro, D., (2009) Archaeobotanical Online Tutorial http://archaeobotany.dept.shef.ac.uk/ https://sites.google.com/sheffield.ac.uk/archaeobotany/tubers/identification/ranunculus-ficaria

[2] Mithen S, et al. 2001. Plant use in the Mesolithic: evidence from Staosnaig, Isle of Colonsay, Scotland. Journal of Archaeological Science 28, 223-234, https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1999.053 (Institutional or paid access only).

[3] Dickson C & Dickson J. 2000. Plants and people in ancient Scotland. Tempus Publishing, Stroud, UK.

[4] Pilewort as a poisonous plant. 1) Long HC 1927. Poisonous plants on the farm. MAFF, HMSO, London. 2) Forsyth AA. 1954 (1968) British Poisonous plants. MAFF Bulletin 161, HMSO, London. 3) Cooper MR, Johnson AW 1984 Poisonous plants in Britain. MAFF Reference book 161, HMSO, London.

[5] Grigson G. 1958. The Englishman’s flora. Paperback 1975 by Paladin.

[6] Grieve M. 1931. A modern herbal. Now online, read the page on lesser celandine at botanical.com.

[7] Anton Kerner von Marilaun. 1894 (English edition). The Natural history of plants. Translated by FW Oliver. Blackie and Son, London.

[8] Stace AC 1997 (second edition) New Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge University Press.