This is the Living Field web page for Sarah Doherty’s Beans on toast project [1, 2]. Here she will explain the things that go into the making of this well loved dish. She will look inside the tin of beans, the loaf of bread and the tub of spread, asking questions of how much water is used in growing the crops and processing the harvest.

More than just beans …

Ten crops and a few bathfulls of water …

Beans, bread and spread

weight when fresh = 300 g, weight when dried = 120 g

therefore the water content is (180/300)*100 = 60%

In the simple calculation above, the beans straight out of the tin, plus two slices of bread, plus a layer of spread make up the fresh weight (in grams). The three constituents were then dried in an oven at 70 C to get their dry weight. The water content is the difference between fresh and dry weights and was 180 g. The percentage water content was calculated as weight of water over the fresh weight multiplied by 100.

But …. the water content of food is only a fraction of the total water neded to produce the food.

How much water is needed in the production process? Where does it come from? Where does it go?

Here is the story of how water is used to make beans on toast ….. Have you ever stopped to look at the packaging on your food? How is it that so many ingredients are used, even to make some of the simplest items? When you stop and think about just how many components there are, where they’ve come from and how they’ve been made – it’s really quite staggering!

The tin of beans

Although at first glance beans on toast may be a relatively simple meal, breaking it down into its individual ingredients can be quite complex. We will now trace the many ingredients back to where they came from and show how water is used in the production process.

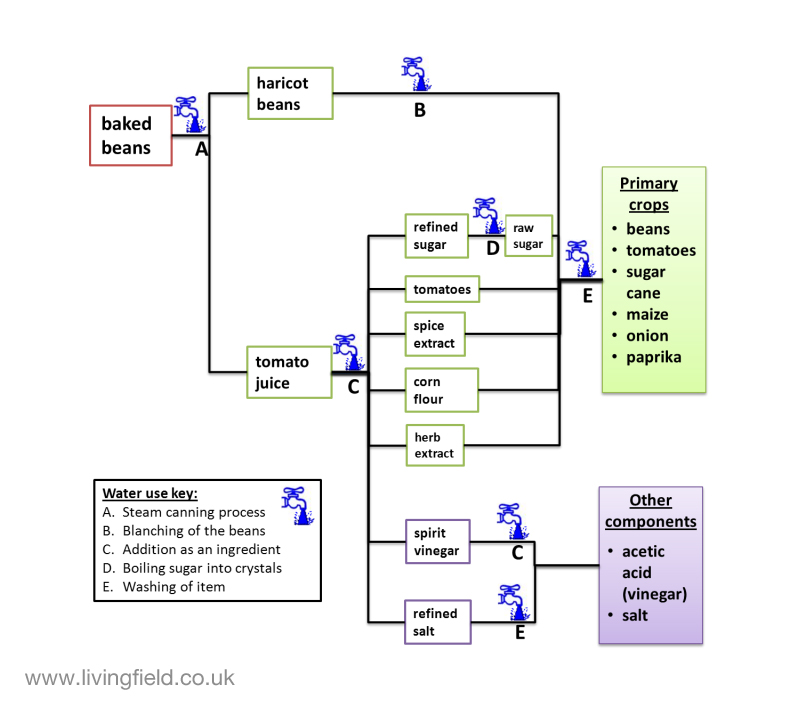

The diagram below shows the breakdown of the contents in a tin of baked beans into the primary components from which it originated. The first step was to note down the ingredients on the label of the tin. Different brands have slight variations, but for the purpose of this research, the ingredients are based on a standard tin of beans.

The diagram is split into two main sections: the beans and the tomato sauce or juice. The sauce contains eight ingredients, six of which came from crops, and two from other sources (salt and acetic acid). The crops in total were haricot beans, tomato, sugar cane, maize, onion and paprika.

In order to reach the tinned state, the primary components have undergone many industrial processes, most of which use water along the way. The taps therefore highlight the key areas of water use during processing.

The slice of bread

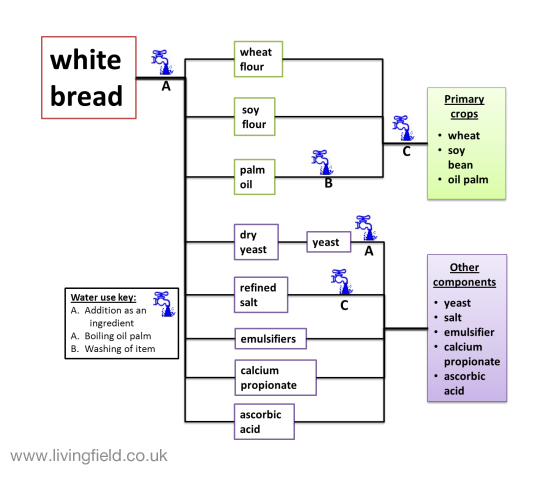

White bread – sliced, ready to toast. What goes into an average loaf of white bread?

The diagram below shows what goes into an average loaf of white bread. There are lots of added ingredients compared to a homemade version aren’t there? Apart from the wheat (for the flour), two other crops are used: soybean and oil palm.

Soybean is used in this case to produce soy flour, a component which improves the moisture, texture and strength of the bread. The oil palm produces an oil which is used to achieve a good texture and softness.

Many of the industrial processes needed to make the other components are difficult to find out, but the key, known areas for water use can be seen by the tap symbols.

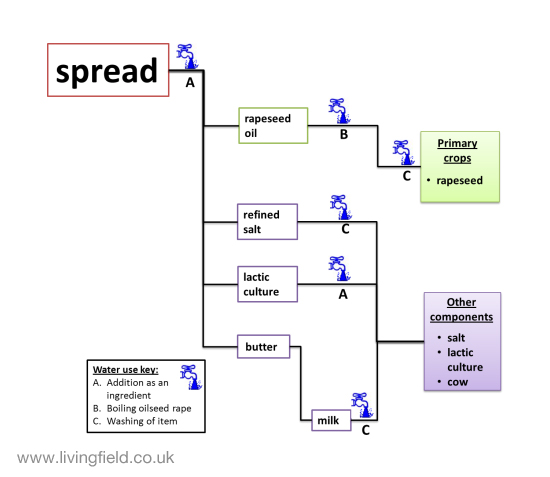

The slither of spread

Some people use pure butter, some have nothing at all. Most people, however use some sort of spread with their beans on toast.

One of the more common brands was used for the ingredients in the diagram below. Although this spread contains butter, there are plenty of spreads that do not contain animal products; these are normally based on a mixture of vegetable oils. The main oil that is in this particular spread is from oilseed rape, used to improve spreadability.

Common oils used for spreads include soybean, oilseed rape (rapeseed or canola), sunflower, olive, cottonseed, and corn oil. Oils tend to be chosen depending on what overall type of spread is wanted: for example, health spreads (low fat, dairy-free, cholesterol lowering, salt-free etc.), cooking spreads, functional spreads (e.g. those with added benefits such as omega-3), or those chosen simply to bring out different tastes.

It is also clear from the diagram that water is used in many processes in converting the raw materials to spread in the container.

In all, the crops that go to make a plate of beans on toast include the legumes haricot bean and soy bean; the cereals and grass crops wheat, maize and sugar cane; the vegetables, tomato and onion; the oils rapeseed and palm oil; the spice paprika; grass for the cows if the spread contains milk; and several other ingredients some of which originate as by-products of other crops.

A global product

Quite a list of crops! And none of them except rapeseed is grown locally, and even the rapeseed probably comes from abroad.

Now that we have looked at what goes into a plate of beans on toast, it is time to examine the water used to grow and make each component. For the page on water content, please go to “Seed to sewer” (Ed. in progress ….. January 2018).

Sources, links

[1] Sarah Doherty worked on her Beans on Toast project while visiting the James Hutton Institute as a student from the University of Durham UK.

[2] CREW Scotland’s Centre of Expertise for Waters funded Sarah during her stay at the Institute.