Raghnaid Sandilands describes a community growing project in Strathnairn and introduces a new venture with ancient cereal grains.

Fearnag Growers is a communal growing project based in a beautiful old walled garden at Farr estate on South Loch Ness. It has been worked by the community since 2016 and treasured by the allotment holders, a life line through the lockdowns.

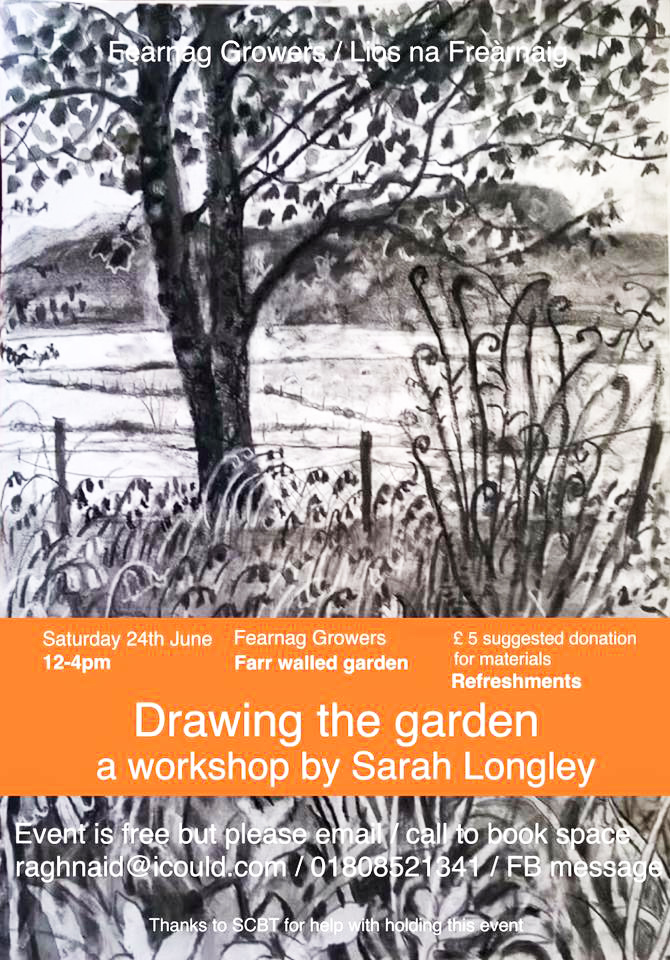

Over the years we have become a small hub for cultural and communal events, hosting a wide variety of events – a Gaelic plant lore walk at midsummer with expert Roddy MacLean, drawing the garden days with artists Sarah Longely and Maureen Shaw, a hut raising day, a woodworking workshop for children and an alfresco traditional music session, are among some of the community building days we’ve had together.

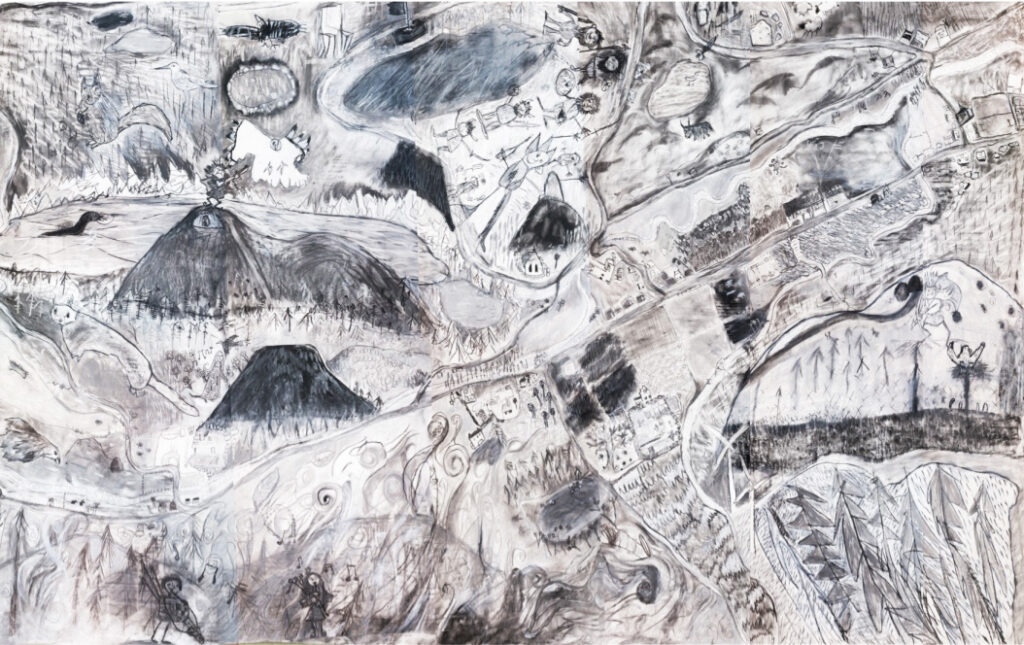

Some of the photographs on this page show the Fèis Farr ‘Mapa Mòr’ – a huge charcoal map showing some characters from local stories and wildlife too, along with places that are important to the children, the allotments among them.

Ancient and unusual grains – April 2021

In late April a gathering of individuals of all ages came together at Fearnag Growers to communally sow and plant a number of different types of ancient and unusual grains. The sun shone and we had a morning to gladden the heart, working together and planting small patches of emmer, eikorn, naked barley and oats, Bere barley, Shetland Aets, and other heritage varieties of wheat and barley. Col Gordon from Easter Ross, grain expert and enthusiast, gave us direction and spoke with conviction about his passion for grains.

Grains are the staples foods of most of our cultures, but the growing of them today as monocrops or monocultures has become something very far removed from most folk.

Our major grains have very long histories. Barley and wheat began to develop in the Fertile Crescent around 10,000 years ago and are directly tied to the spread and development of Eurasian civilization. Rye and oats came later to our lands.

Easy to transport and store and very adaptable, these grains migrated across the globe, developing alongside peoples and their cultures. There are thought to be tens if not hundreds of thousands of cereal landraces globally. Landraces are now critically threatened.

In recent decades, more of the world has abandoned traditional farming and seeds and adopted more industrial systems and modern seed varieties. When this happens, the genetic diversity built up, in some cases for millenia, can disappear very quickly. Today very few grain varieties are commercially available and all have been bred to work alongside high-input chemical farming.

Whereas in the past, every region in the British Isles would have a few locally adapted varieties and landraces and maybe some local customs and traditions that would accompany them, these have practically all disappeared now. Luckily, some folk had the foresight to see this happening and began to gather as much of the world’s genetic material as they were able to preserve in gene banks.

If it wasn’t for these people we truly would have lost most of these varieties. But as John Letts used to say, a mentor for Col Gordon, rather than in these gene banks “the safest places for these seeds are the farmer’s fields.”

Grains in tradition

Farmers and crop scientists are starting to understand that modern varieties, which are bred for yield above all else, are not suited to low input growing or changing climatic conditions, not to mention flavour and nutrition. But we don’t often consider the damage done by disconnecting our grains from their histories, places, peoples or cultures. Each of these older seed varieties belongs to a distinct culture and place. There are likely all sorts of traditions, stories and myths, rituals, songs and festivals that are associated with a lot of them.

Col spoke to us about the need to stop thinking about grains and farming purely in terms of production and instead rediscover and repair once again the cultural aspects that make old agrarian systems beautiful. To do this may require us to question the limits of, for instance, efficiency and try to find a scale where grains are able to be surrounded by song again. While Rachel Carson’s “the silent spring” has made us question our trajectory of progress from an ecological point of view, Col suggests there may be need for a title “The songless harvest” from a cultural point of view.

Looking at all the things that have been lost in the name of speed, yield and efficiency, Col suggested that these are the kind of questions we need to be asking more.

Reconnecting with our farming culture

At Fearnag Growers we hope to play a small part in passing on some of this seed but also try to reconnect with some of the cultural aspects of grain. In September we hope the build another communal event around the harvesting and preparation of the grain. There may be food and songs too.

Col Gordon – hear more from Col and his own story in his recent Farmarama podcast series ‘Landed – the family farm (episode 1)’ He speaks in episode 2 to Raghnaid Sandilands of Fearnag Growers about her creative ethnology work and Gaelic.

Sources | Links

[1] Fearnag Growers Facebook page.

[2] Farmarama: more at https://farmerama.co/

Contact: raghnaid@icloud.com

Editor: The Living Field thanks Raghnaid for telling us about Fearnag Growers. We look forward to hearing more at grain harvest later in the year.

Please note that the photographs taken in the garden pre-date social distancing.