The historic watermill at Blair Atholl. Absence of corn growing in the surrounding area today. Extensive field systems and enclosed land in the mid 1700s. Andrew Wights 1780s descriptions of innovation, enterprise and crop diversification. Part of a Living Field series on old corn mills.

The watermill at Atholl [1] offers a welcoming break to journeys along the A9 road, offering – in addition to the working mill – coffee and freshly baked bread from a variety of grains. In 2017, the mill and its bakers gained some deserved exposure on a BBC2 television programme, Nadiya’s British Food Adventure, presented by Nadiya Hussain [1].

The remaining corn mills in the north of Britain tell much about the phasing in and out of local corn production over the last few centuries. The Living Field’s interest in this case lies in the mill’s history and location, being a substantial building but presently in an area that has no local corn production. In this, it differs from Barony Mills in Orkney which lies within an area of barley cultivation that still supplies the mill [2].

The images above show the water wheel fed by a lode that runs from the river Tilt to the north, the main grinding wheel (covered, top l), hoppers feeding the wheel and an old mill wheel. The watermill’s web site [1] and the explanation boards in the mill itself describe the history of the building and workings of the machinery.

The images above show the water wheel fed by a lode that runs from the river Tilt to the north, the main grinding wheel (covered, top l), hoppers feeding the wheel and an old mill wheel. The watermill’s web site [1] and the explanation boards in the mill itself describe the history of the building and workings of the machinery.

The Atholl watermill was a substantial investment, but what strikes today is the absence of corn-growing (arable) land in the area. When visited in 2017, very few fields were cultivated.

What do the historical maps tell us?

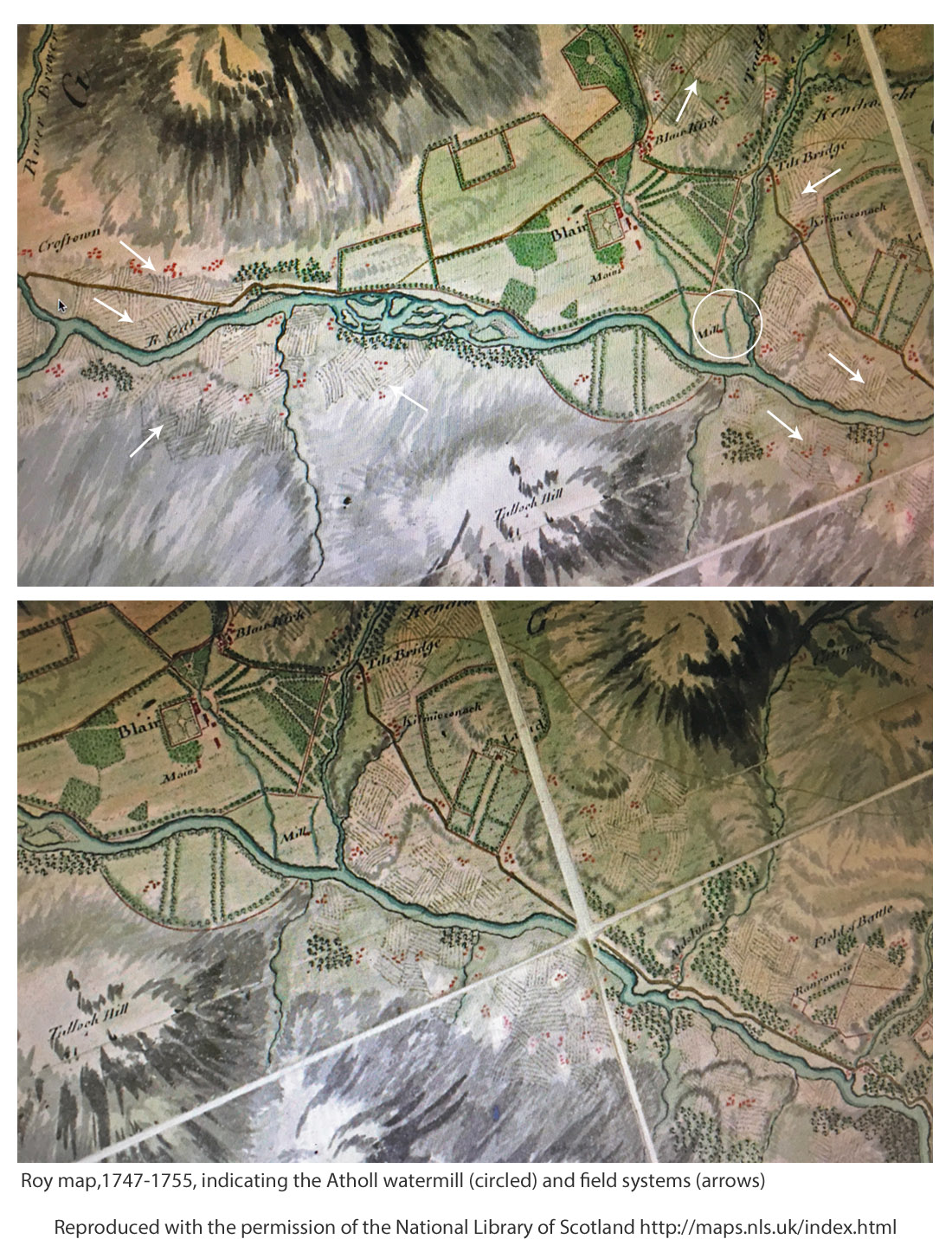

The information inside the mill states that it was present at the time of Timothy Pont’s map of the 1590s [3]. It is there on his map, just south of ‘Blair Castel’. But Roy’s Military Survey [4] of the mid-1700s gives the best indication of the possible extent of cropped land in the area. Features on the Roy map (copied below) include ‘Blair Kirk’ (church) which still stands at what is now known as Old Blair and ‘Tilt Bridge’ on the road that ran north of the Garry; then areas of enclosed land or parkland, bounded by tree lines; and the Mill, shown within the white circle in the upper map, with its lode clearly leaving the River Tilt to the north and flowing past the mill to enter the River Garry upstream of where the Tilt joins it.

The Roy Map shows what appear be clusters of field systems on both sides of the Garry, depicted by short parallel lines suggesting rigs, some indicated by white arrows on the upper map. The lower map has been displaced to show more field systems around Aldclune.

Later, on the first edition of the Ordnance Survey 1843-1882, the village of ‘Blair Athole’ has started to take shape, the corn mill is marked being fed by a Mill Lead originating at a sluice off the River Tilt. Later still, the Land Utilisation Survey 1931-1935 shows arable land remaining, consistent with the location of many of the field systems on Roy’s map.

Therefore crops, and they must have included corn, whether oat or barley, were grown in the region and presumably fed the mill, but more information on what was grown was reported by Andrew Wight, travelling 30 years or so after Roy.

Andrew Wight’s survey of 1784

Mr Wight’s surveys of agriculture in Scotland in the 1770s and 1780s again provide rare and sometimes surprising insights. He meets and reports on mainly the improvers, the landowners and their major tenants, less so the householder and small grower. Yet he was there at a crucial time in the development of food production and able to present a unique and consistent account throughout mainland Scotland.

Part way through his fourth survey [6], he spent the night in Dalwhinnie, then on travelling south towards lowland Perthshire, he stopped at Dalnacardoch, commenting that the innkeeper was a ‘spirited and enterprising’ farmer. There he reports a “clover field, dressed to perfection; an extraordinary sight in this barren country” and also “turnips in drills in perfect good order, pease broadcast, bear and oats with grass-seeds”, and notes ‘great crops of potato are raised here’. [Ed: bere is a landrace of barley.]

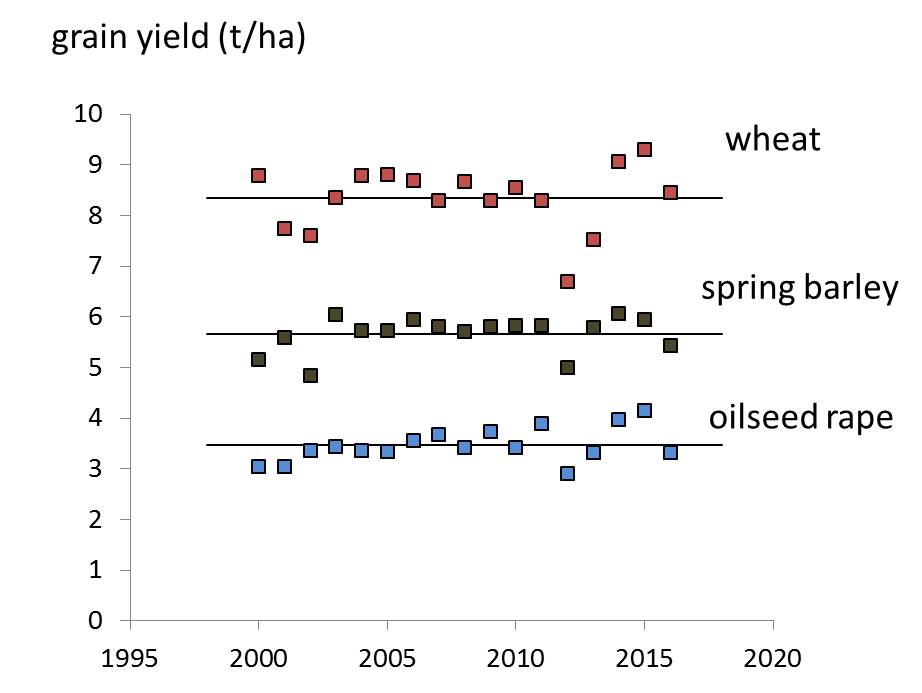

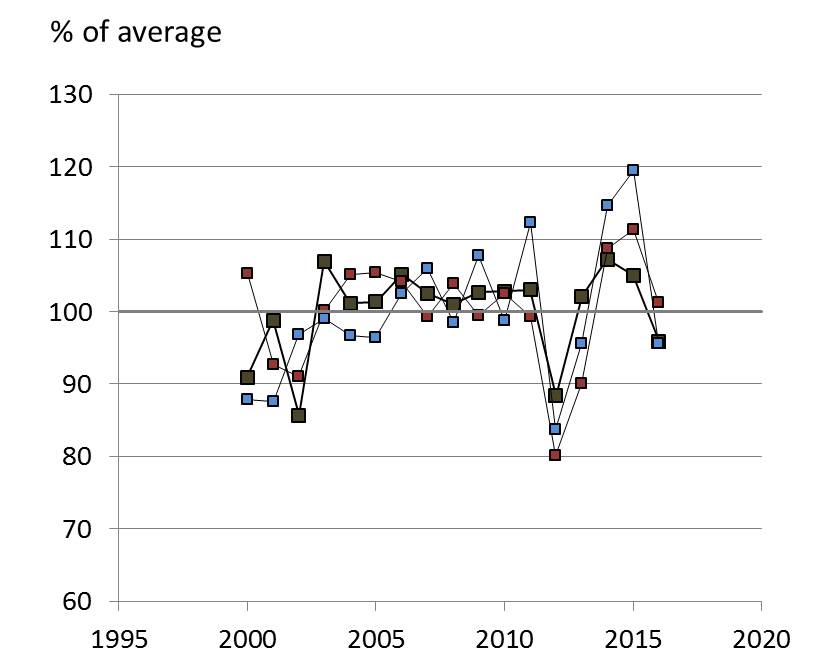

On ‘Athol House’ (near the mill) he concentrates on the animals, various breeds and hybrids of cattle, and also sheep; but on the tilled land, he writes the “Duke’s farm is about 700 acres arable; of which not more than 120 are in tillage, the rest being hay or pasture.” The rotation is “turnip broadcast, barley, oats and turnip again”. So corn crops – barley and oats – occupied 2/3 of the 120 acres, equivalent to 80 acres or 32 hectares (abbreviated to ha, 1 acre = 0.405 ha). It is uncertain what this land yielded at that time, but assuming it was 1 t/ha or one-fifth of todays typical spring cereal harvest, then that’s 30 tonnes of corn annually. By itself it does not seem enough for such a big mill.

Again, it is unclear whether tenants and crofters are included in the stated area, but they were probably not. For example, later he mentions tenants, including the innkeeper and farmer at ‘Blair of Athol’ who grew corn for his own local consumption. The extent of other corn land cultivated by small tenants, for example, on the field systems shown in the maps above, is not mentioned.

Mr Wight continues in his appreciation of the standards as he moves south, finding after Killicrankie and towards Faskally, an enchantment of orderly farmland. On the road south to Dunkeld, he writes ‘hills on every side, some covered with flocks, some with trees and small plantations, mixed with spots of corn scattered here and there; and beautiful haughs variegated with flax, corn and grass.’

Driving along the A9 road today, the land flanking the Garry seems impoverished and the climate inhospitable for crops, but Wight presents an entirely different view: innovation, improvement, and diversity of plant and animal husbandry. As in many upland areas, the land reverted to poor pasture, in some instances as recently as the 1980s. Why? Higher costs of growing crops, low profit margins, easier alternatives based on better transport connections and ready imports of cereal carbs.

Sources, links

[1] Blair Atholl Watermill and tearoom. Location shown on map, right. http://blairathollwatermill.co.uk (check web site for opening). The mill and its bakers were featured in 2017 on BBC2’s Nadiya’s British Food Adventure.

[1] Blair Atholl Watermill and tearoom. Location shown on map, right. http://blairathollwatermill.co.uk (check web site for opening). The mill and its bakers were featured in 2017 on BBC2’s Nadiya’s British Food Adventure.

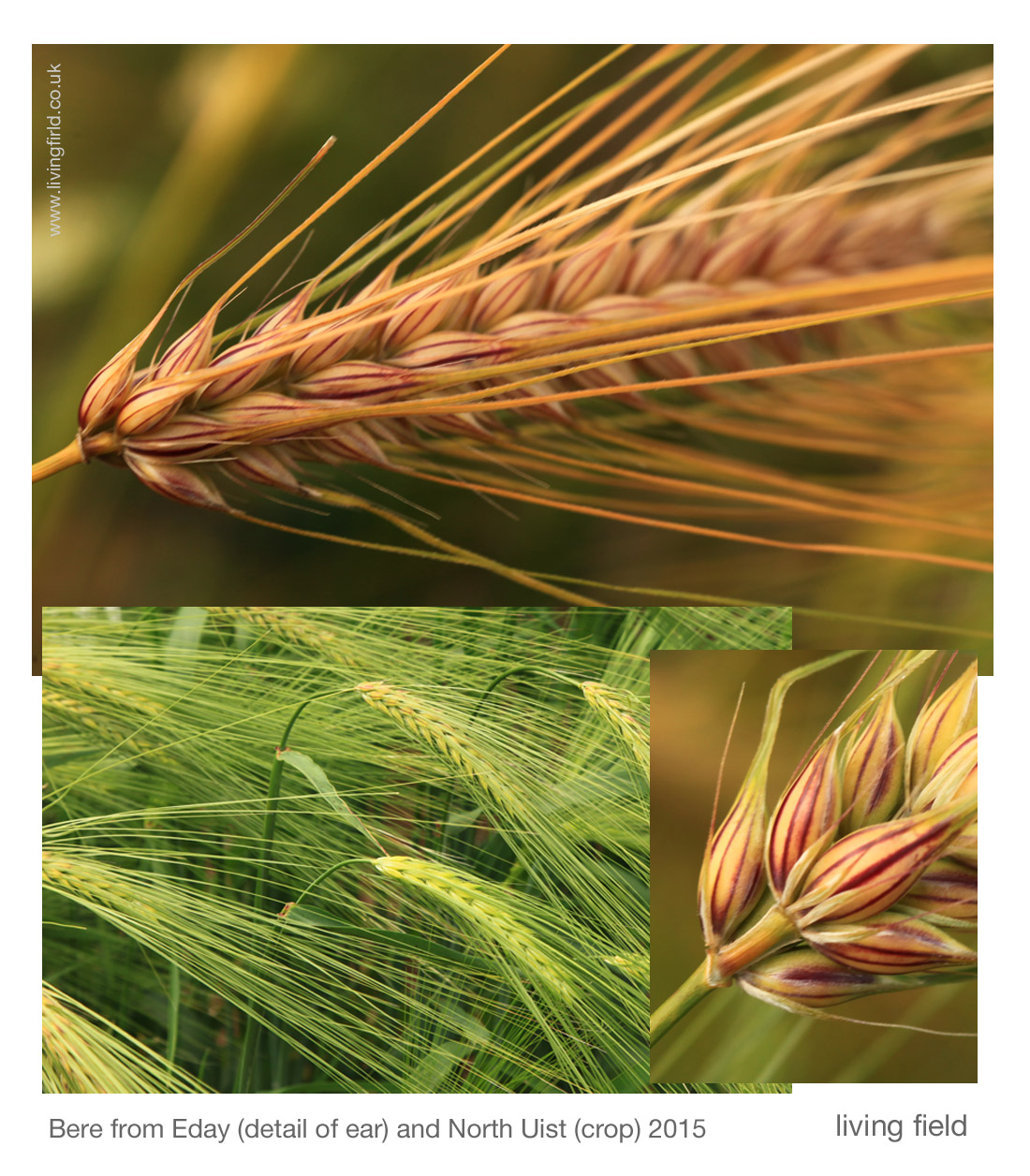

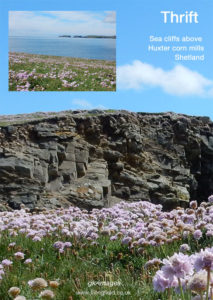

[2] Living Field articles on water-driven corn mills: 1) Shetland’s horizontal water mills and 2) Landrace 1 – bere (Barony Mills, Orkney).

[3] Pont maps of Scotland ca. 1583-1614, by Timothy Pont http://maps.nls.uk/pont/index.html

[4] Roy Military Survey of Scotland 1747-1755 http://maps.nls.uk/roy/ The web site of the National Library of Scotland (NLS) allows educational and not-for-profit use: acknowledgement given on the map legend.

[5] Land Utilisation Survey Scotland 1931-1935. “The first systematic and comprehensive depiction of the land cover and use in Scotland under the supervision of L. Dudley Stamp” http://maps.nls.uk/series/land-utilisation-survey/ See also

https://digimap.edina.ac.uk/webhelp/environment/data_information/dudleystamp.htm

[6] Wight, Andrew. 1784. Present state of husbandry in Scotland Volume IV, part I. Edinburgh: William Creech. The sights noted above, between Dalwinnie and Dunkeld, are described at pages154-165. [Available online, search for author and title.] Other reports of Mr Wight’s journeys are given on this site at Great quantities of Aquavitae and Great quantities of Aquavitae II.