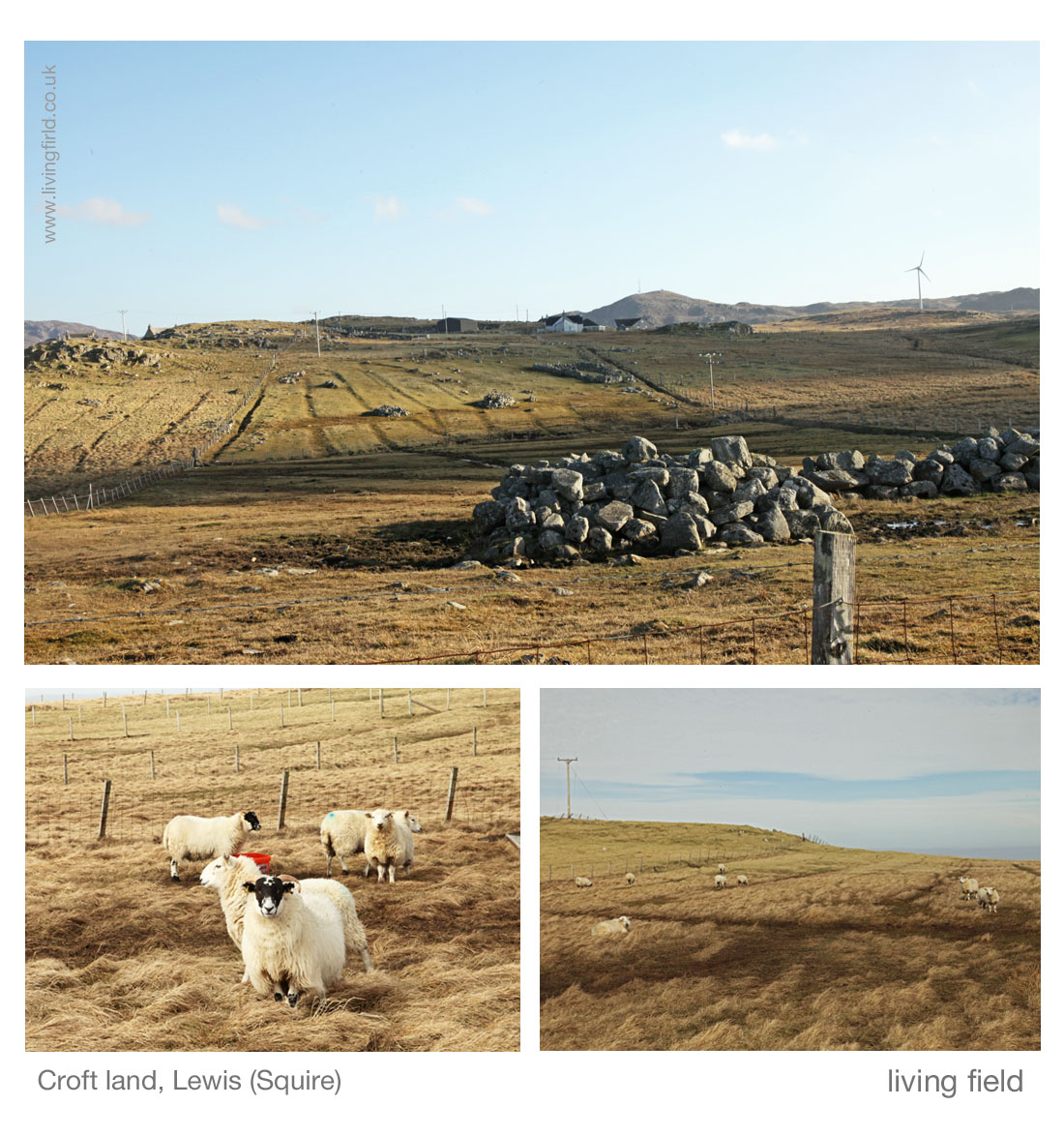

Remote, extensive rig system (lazy beds), north Lewis; historical records of crops from 1690s; bere and barley; subsistence farming on the atlantic edge.

One of the remotest field systems in Europe lies near Eoropaidh (Eoropie) on the north-west coast of the Island of Lewis, facing the Atlantic at 58 N. Continue round that parallel and you’ll cross Quebec in Canada, the Gulf of Alaska and Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula.

The Butt of Lewis lighthouse [1] lies at the northern tip of the Island. As you walk south west from there, the soil and grassy vegetation appear to be slipping towards the cliffs and into the sea.

A little farther south, and the cliffs descend to a rocky shore where the rigs or lazy beds were cultivated close to the tide. It’s a stunning position – go west and there’s no more land until north America. And what Atlantic storms there must be. Yet corn and other crops were grown here.

As testament, the rigs remain as long, grass-covered mounds 5 to 6 m between the furrows, some at more or less right angles to the coastline, others parallel to it. Earth was dug and piled from both sides into the centre and seaweed carried from the beaches and heaped on as fertiliser. Excess water ran down the furrows.

Extensive field systems

Extensive field systems

The rigs in the images are one of several field systems around Eoropaidh and Butt of Lewis. The Canmore web site [2] describes the field system in the photographs here, which lies south west of the lighthouse and facing west, and several others (round the ‘top’) to the south east of the lighthouse. All are abandoned.

They are considered to be post-mediaeval but period uncertain.

Aerial photographs are given for each location on the Canmore site [2] and other pages on that site tell more of the history of the area [3].

Lazy Hardly. Lazy beds in various parts of Scotland and Ireland were constructed to different designs. They are of various widths and heights. One explanation of the word is that they are made, not by digging up and completely turning sods of earth and grass, but rather cutting the sod on three sides, then flipping it over the uncut side to form a double layer – soil, vegetation, vegetation, soil. The method is shown in some recent videos [4].

But the most likely meaning is indicated by Fenton [4] as ‘from an obsolete sense of the English word (lazy), meaning uncultivated’, and refers to the fact that the raised bed is made on top of a strip of uncultivated ground.

Maintaining fertile rigs of the extent seen today around Eoropaidh was a major undertaking, needing the work of (according to Martin below) probably hundreds of people each year.

The method by which this land was managed is known as runrig, ‘a system of joint landholding by which each tenant had several detached rigs allocated in rotation by lot each year, so that each would have a share in turn of the more fertile land’ [5].

Fenton and Veitch (2011) give explanations and many references to the runrig system in different parts of Scotland.

Historical records

Several accounts of the area were made from the 1690s onwards, but they make no mention of the field systems and give little information on the crops and methods of husbandry.

Why this omission? The extensive rigs must have been there during one or more of these accounts, The landforms look impressive to us today, the result of decades, centuries, of hard work, and continued upkeep.

Martin Martin’s visit in the 1690s

Martin Martin, from Skye, visited Lewis in the 1690s and reported his findings in the Description of the Western Isles of Scotland, published 1703 [7]. On soil cultivation, he reported that the people turned the ground with spades; and with wooden harrows for breaking and smoothing the earth, drawn by a man ‘having a strong rope of horse hair across his breast’.

He writes ‘the island was reputed very fruitful in corn, until the late years of scarcity and bad seasons. The corn sown here is barley, oats and rye; and they have also flax and hemp.’ [8] He continues to relate that the main fertiliser is sea-ware but that soot is also used, reportedly causing jaundice in those who eat bread from corn grown on land so treated.

However, there is no mention in his chapter on Lewis of rigs, lazybeds or any means of land-sharing.

Potato is often associated with rig systems but it was not grown in Scotland until several decades after Martin Martin wrote his journal, so it would not have been on the Island when he visited.

A note of caution is due – Martin is not always credible. What a pity when reliable records from that time are so needed! At various places, he related what we would today consider fabulous or supernatural occurrences, without question, as if they happened.

He was knowledgeable about many things, so was he tempting readers with fake news, or did he not check his sources?

Old Statistical Account, 1797

The Rev Donald Macdonald wrote ‘not a single tree, or even any brushwood, to be seen in the whole parish’. The crops were black oats, bear and potatoes, sown April and May, reaped in September and October. (Ed: black oat is Avena strigosa and bere a landrace of barley, Hordeum vulgare).

He confirms the use of soot as fertiliser as reported by Martin a century earlier. He writes that the roof of each house is thatched with stubble and heather ropes (stubble presumably being cereal stems) which become covered in soot due to the burning of peat within. He writes that in the latter end of May when the barley blade (first leaf) appears, the people take the soot and stubble and strew it over the crops as fertiliser.

Many domestic animals were reported – horses, sheep and black cattle, all small in stature. The region was very isolated, things had to be carried to and from Stornoway.

Potato came to the area between Martin’s visit and this account, but there is no mention of rigs or lazybeds. Just that many crude ploughs are found in the parish, consisting of a small piece of crooked wood, guided by a side handle held by a man walking alongside, and pulled by four small horses.

New Statistical Account, 1836

The Rev William Macrae notes also the absence of wood or tree, but that roots and trunk of fir, oak and hazel (with nuts) are ‘imbedded in a great depth of moss, such that wooded land must ‘at some remote period, have undergone some sweeping and desolating revolution’.

He mentions that people eat oat and barley meal, potatoes and milk, but laments the state of farming: that people have not attempted draining or trenching because they were just too hard up, while short tenancies of 6-12 years did not making it worthwhile. It was a subsistence economy with no exports and in no season was produce more than ‘barely sufficient, and sometimes not adequate, to supply the necessities of the tenantry’.

There is no mention of field systems or rigs, and the comment on the absence of drainage is not consistent with what we see today, but he may have been generalising to the whole of Barvas parish rather than these rig systems.

The Rev Macrae commented on many other aspects of life. His account is entertaining, but you feel his mind sometimes strays: he is patient to note among the statistics of population, produce, and adherence to the faith, that ‘The women are modest, comely and many of them good-looking.’

Modern field strips

Visitors today will see the agricultural land in crofting townships on Lewis divided into long thin strips, usually separated by fences. The OS 1:25,000 maps show these bundles of linear features covering much land near the coast.

One of the stated characteristics of linear farming of the type shown above is that, provided the strips run perpendicular to the main gradient in slope or soil, no one strip gets the best land and no one gets the worst.

This sharing of good and bad appears to be one of the reasons why crops, especially in the tropics, are sometimes mixed in a field, not in clumps but in long straight lines [11].

A note on bere and barley

The Living Field has a biding interest in when bere and barley were noted as being different things, e.g. that bere was a primitive landrace of barley. The story unfolds on this site at Bere line – rhymes with hairline.

There is nothing definitive in any of these historical accounts as to whether bere and barley were considered different. In the Old Statistical Account of Barvas parish [9], as noted above, both names are used for the barley crop but neither is defined.

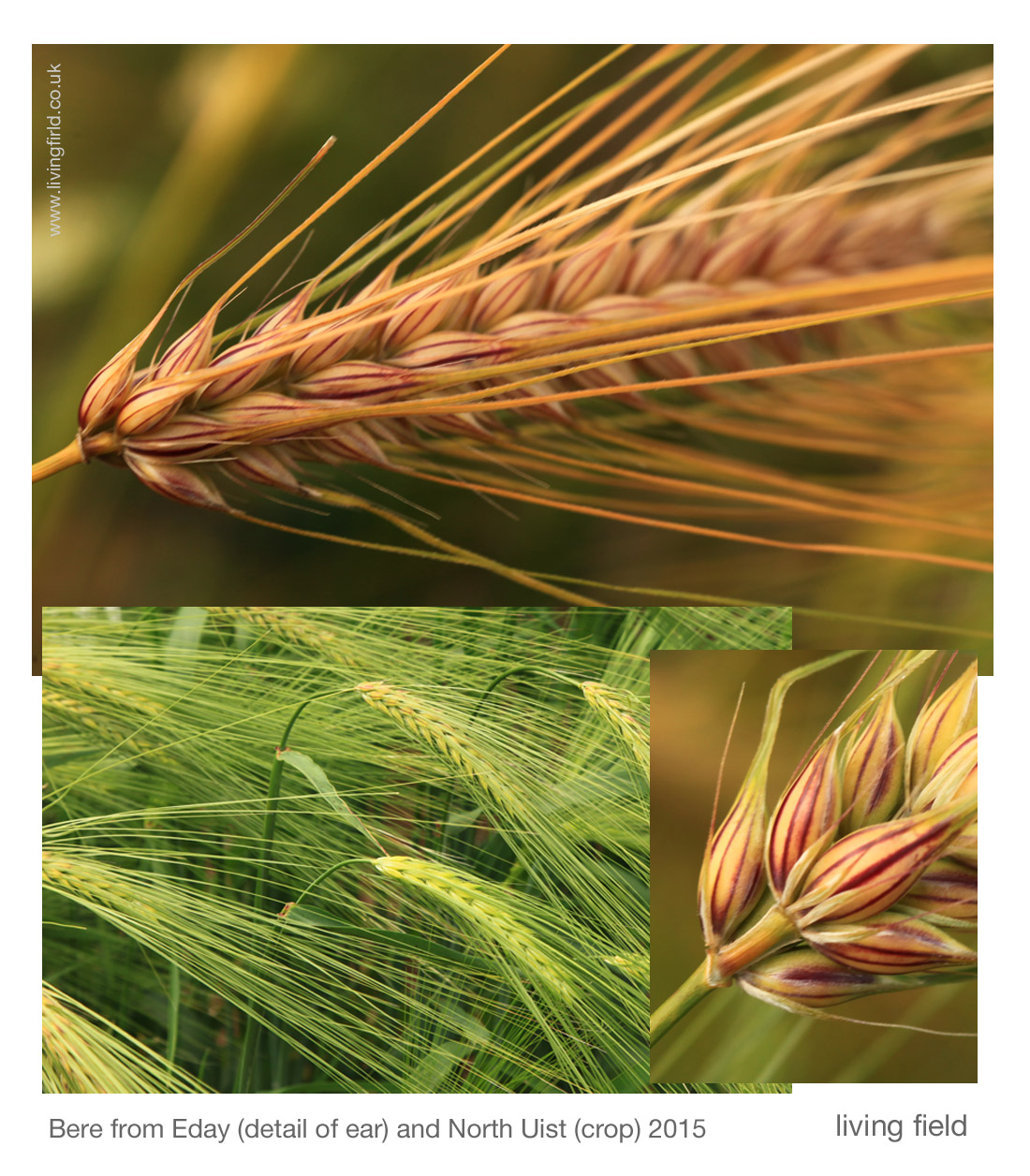

In 2015, the Living Field team grew a range of old barley varieties in the garden, including some bere landraces originating from various parts of the north.

We had none from Lewis, but shown above are bere from North Uist in the Outer Hebrides and from Eday in Orkney. Barley grown in the lazy beds around Eoropie would have looked like this.

An achievement

The land was farmed in this way for centuries, in isolation from much of the rest of the world. Given the location, the rig systems in north Lewis and elsewhere should be seen as a major achievement rather than something to be dismissed as backward (as some travellers did).

Crop production was limited by plant nutrients – nitrogen, phosphate, potash and the many minor elements. Legumes that provided much needed nitrogen by fixation from the air were not mentioned in the historical accounts, and were unlikely to have been planted as crops here as they were during the Improvements era after 1700 in the lowlands.

Apart from seaweed and soot, and probably animal dung, there was no other source of nutrients. To have survived for so long on so little was the achievement.

Author and contact for this article: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk. Thanks to gk-images for allowing us to use some of their photographs.

[Began late March, edited in April and May 2017]

Sources

[1] Northern Lighthouse Board: Butt of Lewis Lighthouse.

[2] Field systems of lazy beds around Eoropie and the Butt of Lewis on the Canmore web site: the one shown in the photographs here is west of Eoropie, Canmore ID 129505. Others include ID 270561, ID 270560 and Dun Eistean ID 4417.

[3] More on the history of the area at the Canmore pages for Eoropie, Teampull Mholuaidh (St Moluag’s).

[3] More on the history of the area at the Canmore pages for Eoropie, Teampull Mholuaidh (St Moluag’s).

[4] Lazy beds: Guthan nan Eilean short video on making lazy beds in Uist (in Gaelic and English versions). A article from Ireland: Lazy beds in the Cooley Mountains. From the Louth Field Names project. The origin of the word lazy, from ‘uncultivated’, is explained by Fenton A, Ch 27, p 673 in Fenton & Veitch 2011 [6].

[5] Definition of runrig in the Concise Scots Dictionary. Ed. Mairi Robinson. 1985. Aberdeen University Press. Also: The runrig system of land tenure, fromThe Angus Macleod Archive via Hebridean Connections.

[6] Fenton A & Veitch K (eds). Farming and the Land. 2011. Publ: John Donald & European Ethnological research Centre. This multi-authored book has many references to runrig and lazybeds, including photograph of lazybeds at Eoropie (p 125); and a note that the runrig system in north Lewis may have been managed by small groups of people, rather than individuals.

[7] Martin Martin, 1703. A description of the Western Islands of Scotland. Printed in London. Available online: search Google Books for the author and title; also the Undiscovered Scotland web site offers the book online (with adverts). Undiscovered Scotland web pages: biography of Martin Martin, died 1719.

[8] Martin is probably referring to the Ill Years, the 1690s when a run of very bad weather caused repeated crop failure and consequently hardship and famine through the north of Britain.

[9] Old Statistical Account of Scotland, 1791-99: Vol XIX dated 1797 for the Parish of Barvas. Online at Old Statistical Account.

[10] New Statistical Account of Scotland, 1834-45: Vol XII for the Parish of Barvas. Online at New Statistical Account and also at Google Books.

[11] As argued in the editor’s account of Mixed cropping in Burma (Myanmar).

And if you are anywhere near latitude 58 N, make a point of visiting the famous –

Information at eoropiedunespark.co.uk