Exploring crop diversity at the Living Field …. new series starting with Crop diversification.

Tag: legume

Lumen print

Lumen print by Kit Martin. See her page on the cyanotype process.

ScoFu: the quest for an indigenous Scottish Tofu

Chantel Davies writes:

As a long-time vegetarian and fan of Asian food, particularly tofu, in recent years I have limited my consumption of soya due to the sustainability issues of soya production and potential negative impacts on health.

Beginnings

My inspiration grew from a Japanese anime series, ‘Yakitate!! Ja-pan’ (i.e ‘Freshly Baked!! Ja-pan’), which follows the adventures of the young protagonist, Kazuma Azuma, as he follows his passion to invent an authentic Japanese bread of which the Japanese people can be proud. In a similar vein, I have embarked on a quest to produce an authentic Scottish tofu, using local ingredients and some gastronomic daring.

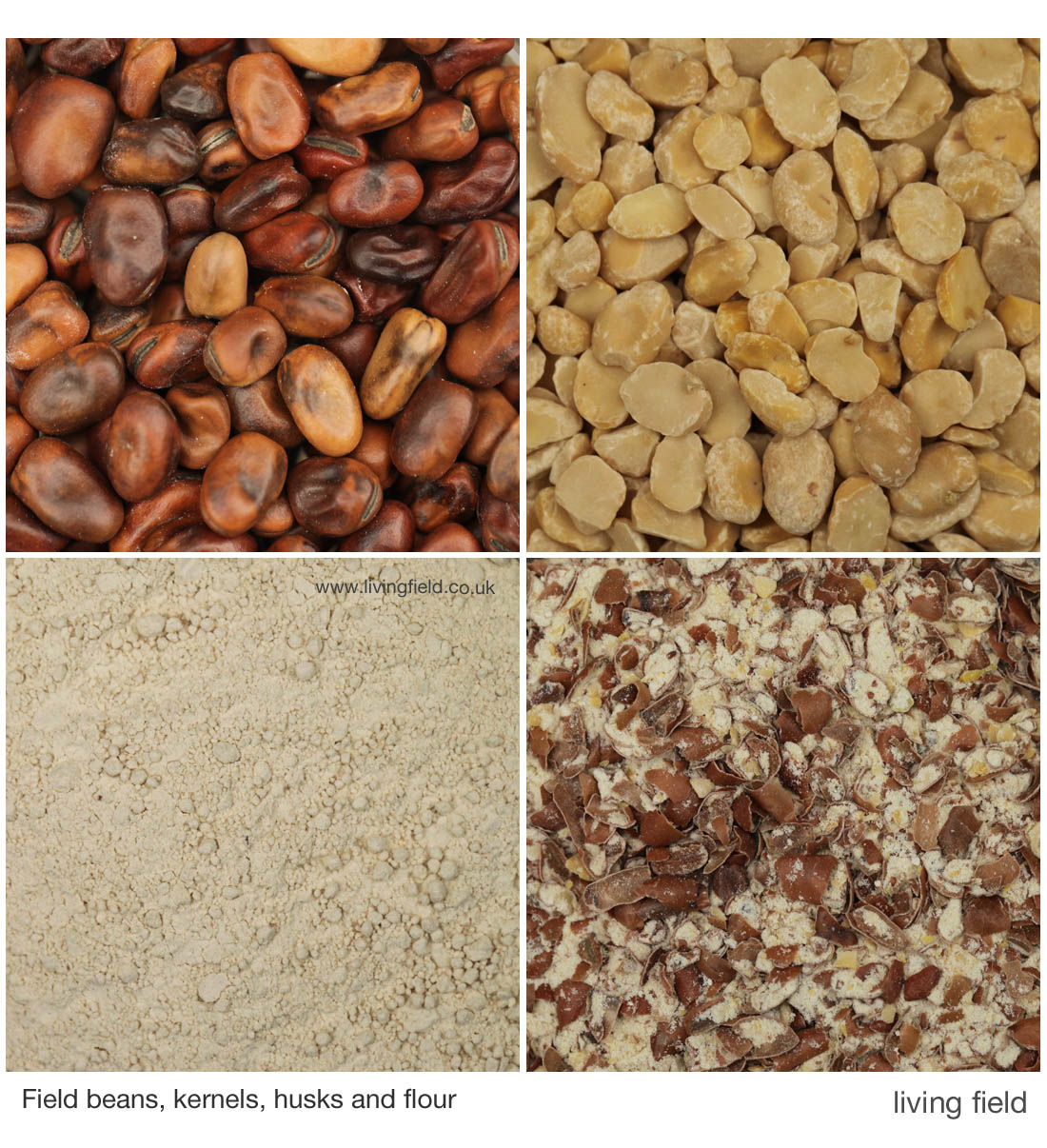

I acquired some faba bean powder (flour) from the Institute’s Pete Iannetta, who is growing beans in experimental fields at the Dundee site (and using them to create new bean-based products including craft beers).

My first experiment, ScoFu No. 1, was to test the production method and make some technical adjustments. It was marginally successful, but the quantity of final product after pressing resembled a crêpe with a lot of left-over okara (bean pulp). Not really what I was aiming for, though the okara could be used for faba bean falafel – an experiment I will save for another time.

ScoFu No. 2

For ScoFu No. 2, I increased the quantity of ingredients and modified the processes. Firstly, I produced the purée. After a bit of culinary alchemy, and a handy little tofu box, I managed to produce a very neat-looking block of tofu (image below).

After a little more magical waving and muttering, the tofu became a delight of pan-fried strips, infused with chilli and garlic, served with spicy rice and a dash of soy sauce. The texture, although soft and crumbly, held together nicely when cutting and cooking.

The flavour was definitely faba bean, with a hint of bitterness due to the preparation method (and maybe the coagulant), but also a touch of umami; beany flavours are often preferred in East Asia. On a firmness scale of 1 to 5, with five being very firm, I would put this at 3.5, or ‘momen-dofu’ as the Japanese would say.

A rather delicious stock was produced in the formation of curds, which could form the base of type of miso soup, or vegetable stock.

Whilst this has been a success, there are so many different variables to consider when making tofu that can influence taste, texture and firmness that I feel my adventure has only just begun. Onward to ScoFu No.3!

Contacts, sources, links

Chantel Davies email: chantel.davies@hutton.ac.uk; c.davies@growing-research.com

The beans used to make the Scofu are locally grown faba beans Vicia faba.

Also on the Living Field web:

Feel the Pulse – our exhibition on beans at Baxter Park with Dundee Science Centre and Legumes in the Living Field garden.

Related: SoScotchBonnet – our search for the truly indigenous crop.

[Published 27 June 2017; updated with new images 21 July]

Fixers 3 Crimson clover

Third in a series on nitrogen fixing legume plants.

The crimson clover Trifolium incarnatum ssp incarnatum was once grown widely in the south of Britain and trialled in the north, where it never found favour as a forage ley compared to the white and red clovers. So a small field of mixed legumes in Tarbat, a few miles south of Portmahomack, was unusual.

Crimson clover was the most visible of the plants, in full flower late September, but the patch also contained red clover, two white- flowered clovers and a few other plants. On its margins a stray sainfoin appeared, probably a relic from a previous sowing.

Crimson clover was noted in Lawson & Son’s Vegetable Products of Scotland (1852). They report that, if sown in autumn, it can be cut in June the next year ‘…. and the land fallowed for wheat or spring corn’. They report that is makes a valuable green food for cattle and when cut in full flower ‘it makes a more abundant crop, and a superior hay to that of common clovers, at least it is more readily eaten by horses’.

They also report a comparison of ‘common crimson clover’, a variety of it named ‘late-flowering crimson clover’ sourced from Toulouse in France, and Moliner’s clover which was said to be grown in France and Switzerland. The late flowering variety came out top.

In modern taxonomy, the only one of these native to Britain is now called long-headed clover Trifolium incarnatum ssp molinerii, white-flowered, but that is found at only a few coastal sites in the south of Britain. This is likely to be the same as the Moliner’s clover mentioned by the Lawsons, but their seed was most likely sourced from European seedsmen rather than from the wild in Britain. Crimson clover is now Trifolium incarnatum ssp incarnatum. Moliner’s and crimson are therefore considered sub-species (ssp) of the same species.

So what was it doing here? It was probably sown in a clover mix as a legume contribution to CAP Greening measures (see Sources). As can be seen the mix was luxuriant in foliage and flower well into autumn, when many other wild plants were dying or seeding.

Tarbat is a rich agricultural region, and you can see why the Picts farmed and established their monastery and unique monuments here over 1000 years ago. Today, small fields and patches like the one shown offer refuge and food for insects and birds in a landscape dominated by grazing land, and harvested or ploughed fields.

Sources

Peter Lawson and Son. 1852. Synopsis of the vegetable products of Scotland. Edinburgh: Private Press of Peter Lawson and Son

Mixtures for CAP Greening and also crimson clover alone: Cotswold Seeds https://www.cotswoldseeds.com/seed-info/greening-and-cap-reform

Taxonomy from: Stace C. 1997. New flora of the British Isles 2nd Edition.

Links to legumes on this web site:

- Fixers 1 – coastal legumes

- Kidney vetch and the small blue

- Fixers 2 – restharrow

- Legumes in the Living Field garden

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk. Images are the property of the Living Field project.

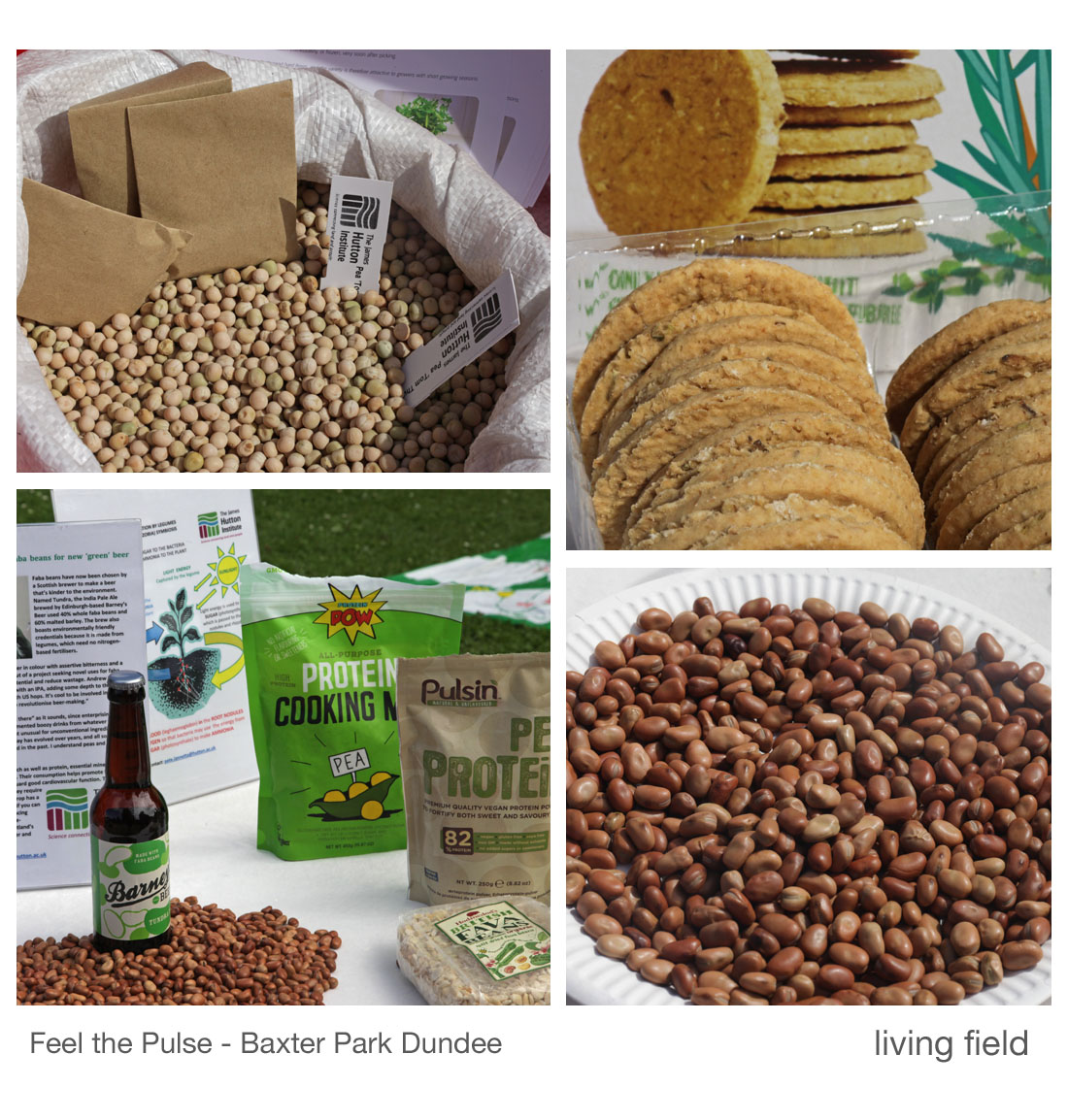

Feel the pulse

With Dundee Science Centre, the James Hutton Institute is contributing to a range of outreach activities in 2016 as part of The Crunch, and initiative headed by the UK-wide Association of Science and Discovery Centres and supported by the Wellcome trust.

Our exhibit at a community-run event in Baxter Park Dundee on 28 July 2016 was called – Feel the Pulse – a display of beans and peas, which along with lentils are known as ‘pulses’ (images below).

Why pulses? They yield a highly nutritious, plant protein that can be grown without nitrogen fertiliser because the plants themselves fix nitrogen gas from the air into their own bodies. Nitrogen is essential for plant growth, but in its mineral form (from bags of fertiliser) can be a serious pollutant, contaminating streams and drinking water.

Once, peas and beans were widely grown and eaten, but the arrival of industrially made nitrogen fertiliser about 100 years ago and the ready import of plant protein from other countries caused pulses to decline as crops.

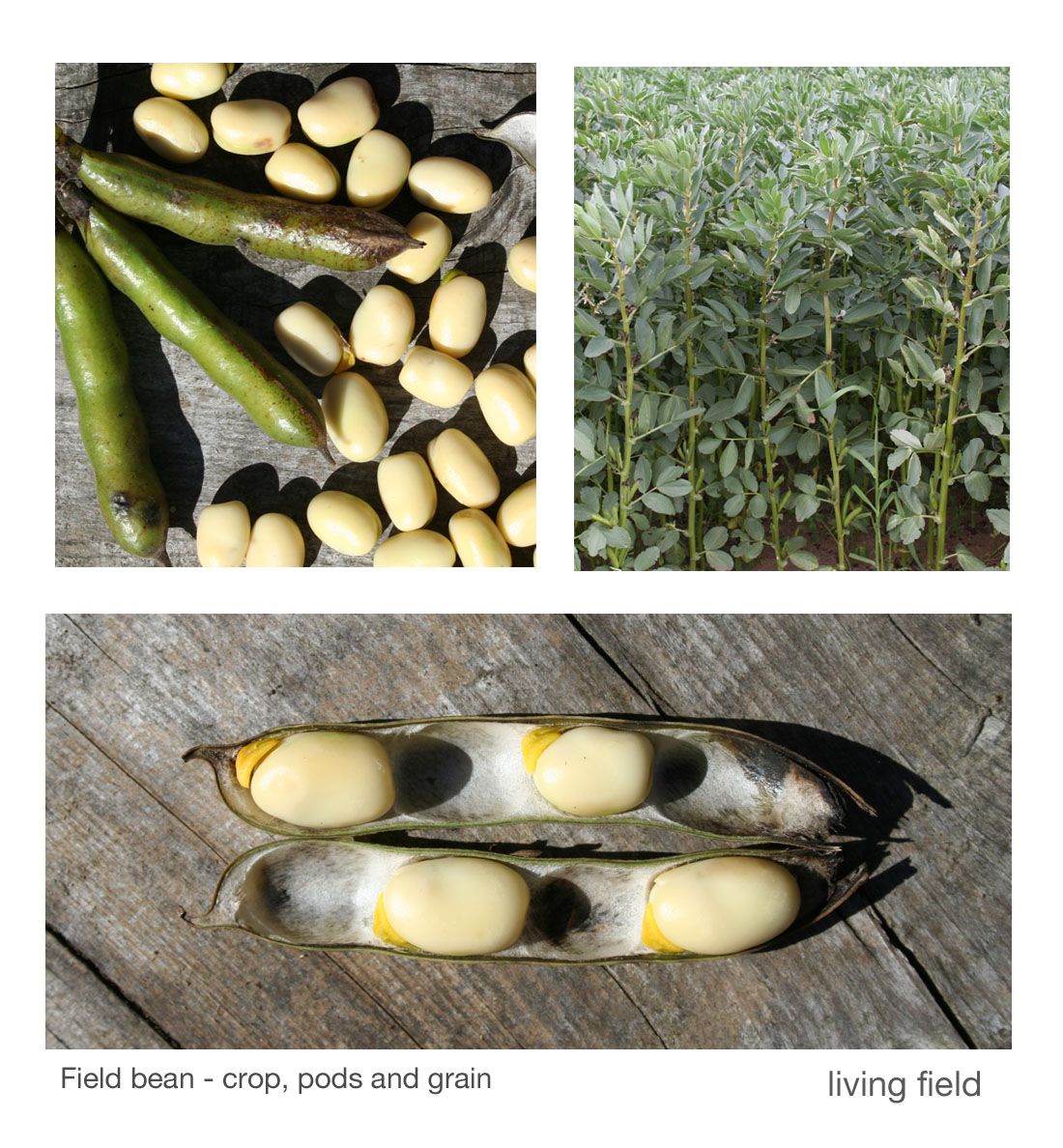

Yet today, pulses are widely acclaimed for their benefits to health and the environment. The field bean Vicia faba crops above were grown locally without nitrogen fertiliser. They also offered a habitat and refuge for insects and small animals.

Is there a way to turn the tide – to farm more locally-grown cereal and legume produce, use less mineral N and support a cleaner environment.

We believe there is but one of the first things to do is to increase awareness of the benefits of peas and beans and similar products.

Our exhibit – Feel the Pulse – shows some of the things that are being done, such as finding types of peas and beans suited to the local conditions, comparing the nutritional value of different pulses and finding new pulse-based products for the market, for example bean bread and bean beer, both made from field bean flour.

Sources, links

Feel the pulse at Picnic in the Park, Baxter Park Dundee, 28 July 2016. Part of The Crunch at Dundee Science Centre.

Contact for pulses: pete.iannetta@hutton.ac.uk

At the event: Pete Iannetta, Philip White, Geoff Squire and Stephanie Frischie, a doctoral student visiting from the NASSTEC (Native Seeds) programme: www.nasstec.eu/home

See also: Bere and cricket

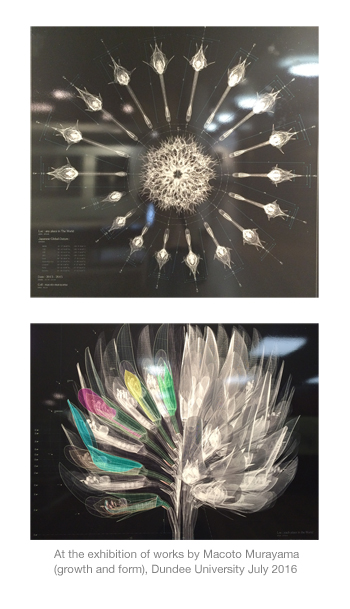

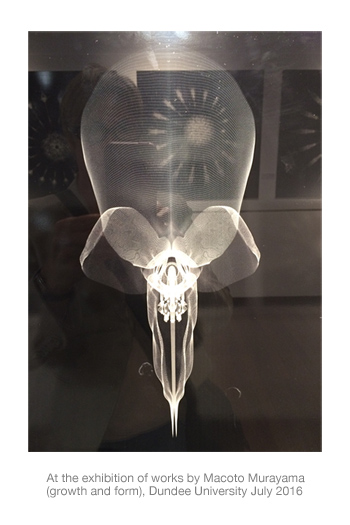

Macoto Murayama and T rep

T rep. The short form given by our field survey teams to white clover Trifolium repens. Still a common plant of pasture and waysides, so common that the intricacies of its structure and  function generally go unnoticed.

function generally go unnoticed.

Yet the mathematical artworks by Macoto Murayama shown in July at Dundee University reveal these intricacies in astonishing detail (image right).

The exhibition was held by courtesy of Frantic Gallery, Tokyo.

The Living Field’s correspondent gk-images sent some cellphone snaps from the exhibition.

The introduction gives some detail of the artist and how he transfers the complex flowering heads and flowers of his botanical subjects to two-dimentional images.

“Macoto Murayama is a Japanese artist who cultivates ‘inorganic flora’. His extraordinary images are created after minutely dissecting real flowers and studying [them] under a microscope. His  drawings are then modelled in 3D imaging software then rendered into 2D compositions on photoshop before being printed on a large scale.”

drawings are then modelled in 3D imaging software then rendered into 2D compositions on photoshop before being printed on a large scale.”

Born in Kanagawa, Japan in 1984 he is now a researcher at Institute of Advanced Media and Art and Sciences, Tokyo.

The photographs, with reflections of lights and the opposite wall are of white clover (top) and spanish broom (lower).

Sources, links

Dundee University – Macoto Murayama: Growth and Form Exhibition. 14 May to 20 August 2016. Lamb Gallery, Tower Building, Dundee. Click the link for opening times.

Macoto Murayama at Frantic gallery: http://frantic.jp/en/artist/artist-murayama.html

Frantic Gallery Tokyo. Looks like some great exhibitions, for example the Universe and other Oddities by Zen Tainaka.

On Growth and form, a classic treatise by D’Arcy Thompson. Web site http://www.darcythompson.org/about.html

Images Thanks to gk-images for the photographs shown here.

Ps Back to T. rep. There would be, in the 1940s, five or six legumes growing as ‘weeds’ in cornfields but they have since been ousted by nitrogen fertiliser and chemical herbicide. Trifolium repens is one of the the last remaining of these nitrogen fixers still found, but then rarely, in arable fields.

Food for small flying and crawling things this wet year

Unremitting wet since solstice-time in late June. The field scabious Knautia arvensis offers bee-food en masse for months in most years, and in June the mauve flowers promised a fine show, already thick with bumble bees.

Since then they have been thrashed by the heavy rain and wind and grasses now dominate the meadow. Yet on the rare sunny afternoon, the insects take their feast on the Garden’s wild plants.

Chief among them are the nitrogen fixing legumes, offering high-nitrogen, high-protein take-away. The images (above, top left clockwise) show white melilot, the blue-flowered tufted vetch, sainfoin, alsike and lucern.

Only the tufted vetch is common in the margins and lanes here. The others have been tried as forages in the past but are now rarely found. Other legumes flowering (not shown) include red and white clover, the yellow-flowering melilot and greater bird’s-foot-trefoil, all well attended by bees.

The other plants that most years offer months of rich flower-food fare no better.The striking, blue viper’s bugloss in the medicinals bed is almost finished bar a few, one of which is shown above right. And the remaining field scabious, bottom left above, will continue to put out their sumptuous floral parts for bees to drain and trash.

Yet again, the benefits of growing in this small space a diversity of native and medicinal plants pays, because teasel, knapweed and greater knapweed, and a set of annual composites including cornflower and corn marigold are all offering their wares in return for chance pollen.

Teasel will now flower along its bristly head for some weeks – the ladybird in the image top left above just slotting in between the spikes, jostling several aphids that may not be visible at this magnification.

What’s to come – the deadnettle family – the labiates – will sustain the insects through to the autumn equinox. Many are only just in flower – betony, wild marjoram, some field mints, hemp-nettles, a calamint, sage, lemon balm and hyssop.

Fixers 2 Restharrow

The restharrow Ononis repens is a tough plant, growing as it does at the very limits of dry, salty land around the coast. There it will fix nitrogen from the air, which finds its way through decomposition of roots and leaves into the sand and then perhaps to other plants and to soil microbes. It was also once a serious weed of cropland, as its name suggests, but a weed no longer, tamed by heavy ploughs and pesticide.

It grows well around the coasts of Angus and Moray. In Montrose bay, it grows in abundance, the main legume of the dunes. It is prolific near the south end, particularly around the car parks, binding the sand as it once slowed the harrow. To the north over the several miles of beach, it lives at the base of the collapsed dunes (images above), leaf and flower blasted by salt and sand grains.

In the images above, the line of stakes leading seaward from the dunes reaches out into the North Sea at its widest and after 650 km of rough water, meets the coast of Denmark. The restharrow is the first line of defence.

Restharrow as a weed

Grigson gives the mediaeval names of the plant, one of which resta bovis translates as ox-stop, and cites a treatise of 1578: ‘the roote is long and limmer, spreading his branches both large and long under the earth, and doth ofttimes let, hinder and staye, both the plough and oxen in toyling the ground’.

In her 1920 book, Winifred Brenchley classed restharrow Ononis repens among ‘coarse growing plants that deteriorate the quality of pasture or meadow’. And in the last century it seems to have been a problem in grass rather than in land that was repeatedly tilled.

Its decline from the community of common weeds is now so great that it is hardly found in farmland. Yet as recently as 1938, H. L. Long wrote “If this weed is plentiful it must be attacked by thorough and regular cutting, liming, complete manuring, and close depasturing with stock. In rare instances it may be desirable to plough up the pasture, give a thorough cleaning and manuring, and again lay down to grass.”

Long placed it in the top 30+ weeds of pasture, but did not always distinguish the spiny Ononis spinosa, which has a more southerly distribution in Britain, from Ononis repens which is the one shown here in the photographs and which was described by Long as having runners, usually spineless and with a strong disagreeable scent.

Grigson relates its presence in pasture as tainting milk, butter and cheese and children chewing its root, which gives it the name wild liquorice.

Restharrow in the Living Field garden

A few patches of restharrow remain in a remote corner of one of the Institute’s farms near Dundee.

To see what it looks like and how it grows, the Living Field garden keeps a small patch of it, originating from seed. Its luxuriant foliage and flowers grow to well over 0.5 m in height and attract a range of insect feeders. It is cut back to 10-20 cm above soil level in autumn, but is otherwise left to itself.

Its leaves and stems are softer in the garden, less wiry than at the edge of the North Sea (comparison above). There are also small variations in geometry of the leaves and sepals.

References and links

Brenchley WE. 1920. Weeds of farm land. Longmans, Green and Co, London. Grigson G. 1958. The Englishman’s flora. (Paladin, 1975). Long HC. 1938. Weeds of grass land. HMSO.

Note: on sampling the coastal plants, Euan James reports nodulation, indicating they are fixing nitrogen.

Contact/date: GS 30 July 2015.

Also on the web site:

- Fixers 1 – coastal legumes, purple milk-vetch, kidney vetch

- Kidney vetch and the small blue

- Fixers 3 – crimson clover

Kidney Vetch and the small blue

The kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria was noted in a recent post about nitrogen-fixers living by the shore on the east coast of Angus. But the kidney vetch has wider acclaim as host of the rare Small Blue butterfly Cupido minimus.

The small blue lays its eggs in the flowering heads of kidney vetch. The hatched larvae then eat the flowers and the developing seed.

However, the range of the butterfly in the north east has decreased in recent years and attempts are being made to record its occurrence. For more on the small blue and current surveys in Scotland –

- Butterfly conservation – small blue

- North East Biodiversity – small blue butterfly project

- East Scotland butterflies – small blue survey

In the latter can be found people to contact if you want to take part in surveys or to report sight of the butterfly.

Kidney vetch

The kidney vetch is one of the nitrogen-fixing legumes that occur in nitrogen-poor, dry and unshaded environments around the coast of eastern Scotland.

Yet it was once considered as a sown forage – a constituent of vegetation managed for stock-feeding. Lawson and Son (1852) write that it ‘does not yield much produce, but is eaten with avidity by horses, sheep and cattle, and also by hares and rabbits, and might therefore be introduced into mixtures for very dry soils’.

In the Garden

The Living Field garden grows kidney vetch in its medicinals collection and in the raised beds that have housed a legume collection over the past few years (images below). It grows well, forming luxuriant clumps up to 30 cm in height, taller than on the coast. The flowers are usually more yellow, less red than on the wild plants.

It flowers and seeds profusely in the garden. Some plants die in the winter, but in the last two years it has regenerated freely from its own dropped seed.

The flower heads

The round ‘wooly’ heads may be confusing at first sight, but each ball consists of usually three separate heads each holding many individual flowers. The three heads do not all flower at the same time.

In the image at the top of the page, the head to the lower right is the latest to flower – some flowers are still in bud while others have the fresh yellow petals emerging from the red calyx tube (which previously enclosed the bud). The head to the left has a mix of new and withered flowers. The largest one, at the top middle and right, has finished flowering: all petals are withered orange, the calyx tubes have turned purple and the hairs have expanded into a whitish mass, protecting the seeds that will form deep in the tubes.

Reference

Lawson and Son. 1852. Synopsis of the vegetable products of Scotland. Authors’ private press, Edinburgh.

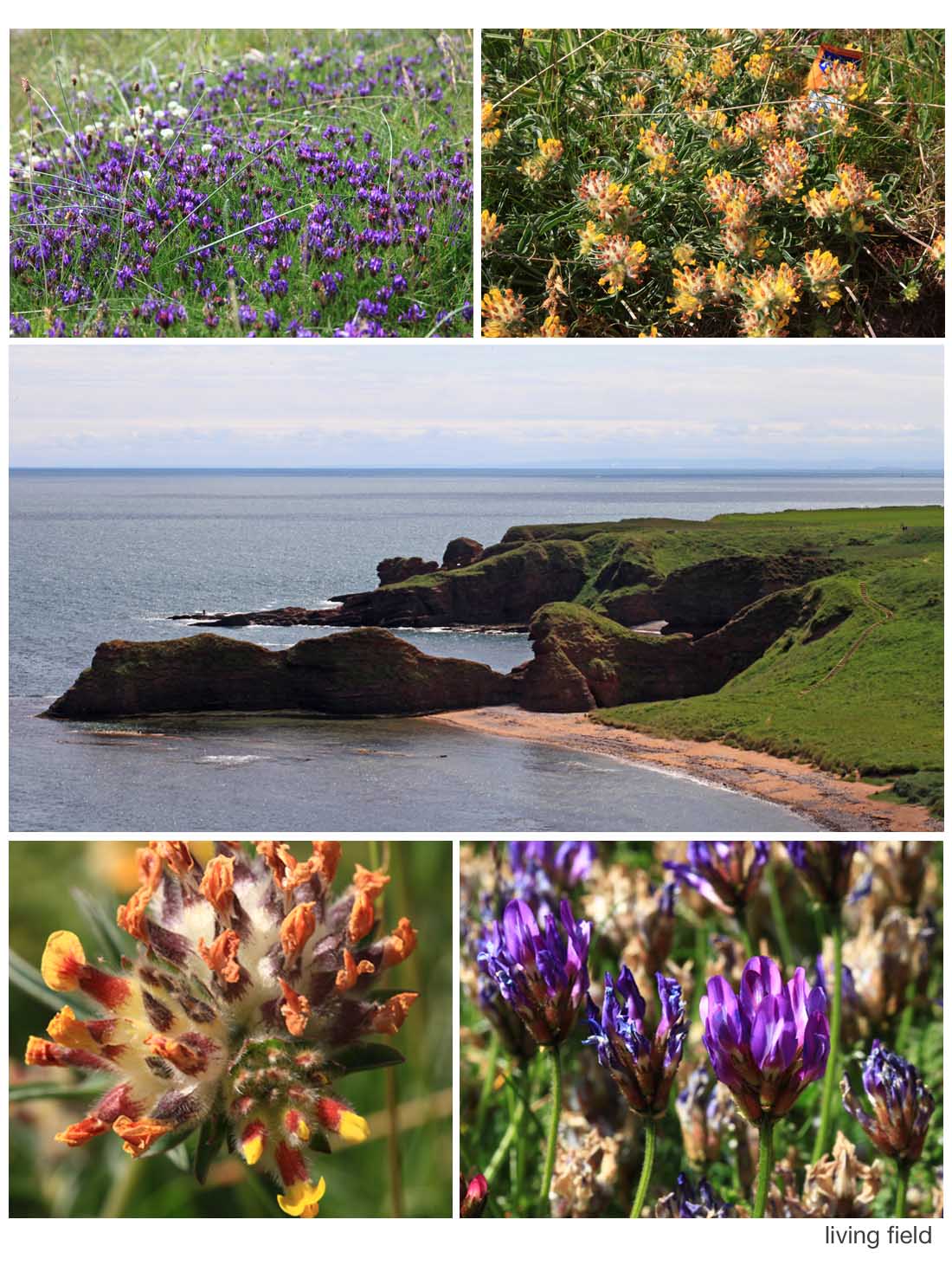

Fixers 1 Coastal legumes

First in a series on nitrogen fixing legume plants.

Legumes are a group of plants that ‘fix’ nitrogen gas from the air to make proteins that are essential for growth and survival. When legume tissue dies, the nitrogen (N) is returned to the soil.

Legumes have many uses to people as food, medicinals and dyes. They also support insects that in turn carry out ecological functions such as scavenging and pollination.

Here we begin a short series on wild N-fixers. First are those that live by the eastern shores of Angus.

The east coast of Angus (middle image) is rich in wild legumes. Those shown here live just above the beach or on top of the cliffs, where the vegetation is short and there are no bigger plants to out-shade them. Top left is a patch of purple milk-vetch Astragalus danicus and white clover Trifolium repens behind, top right kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria with litter, and ( bottom) flowering heads of kidney vetch (left) and purple milk vetch.

Nearby were patches of meadow vetchling Lathyrus pratensis, bird’s-foot-trefoils Lotus species, and on the cliff-tops bush vetch Vicia septum, gorse or whin Ulex europaeus, broom Cytisus scoparius and the introduced laburnum Laburnum anagyroides.

One reason for the presence of legumes here is an unfarmed habitat, low in nitrogen. Fixation by the legumes is one of the main routes by which the plants and soils get their essential nitrogen.

Most of these wild legumes have been tried over the last few thousand years as crops or forages. Some such as kidney vetch have been well-know medicinals (a vulnerary is a herb for treating wounds). Few have remained useful to agriculture, perhaps the best known being white clover, still cultivated today to enrich grass fields with fixed nitrogen.

Legumes are of the pea family Fabaceae, previous known as Leguminosae.

Related on this site:

- Kidney vetch and the small blue

- Fixers 2 – restharrow

- Fixers 3 – crimson clover

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk