Following the Nourish Scotland conference in November 2019, the Living Field began thinking about how it might best support those working towards a sustainable future for food and agriculture [1]. Then early in 2020 the pandemic hit, raising searching questions as to whether the food system could cope.

In March 2020, Pete Ritchie from Nourish Scotland, wrote a blog [2] putting the case that once the initial panic has receded, the international food system would adapt, the empty shelves would be re-stocked and no one in this country ought to go hungry. Nourish, through their blogs, web sites and conferences are at pains to point out that no one should go hungry in the UK because of shortage of food. Where they are hungry or malnourished, it would be due to other factors, such as social inequality, not the amount of food available.

Nourish were correct, but they were not giving the thumbs up to the current state. The blog writes that the food system – “ … generates massive environmental damage, monumental food waste, exploitative work practices and a disastrous mismatch between what we need to eat for health and what we are being sold.”

Dysfunction and mismatch are not simply other people’s problems. The blog continues – “ …..it would be good if Scotland were to produce more of what it eats, and eat more of what it produces.”

The argument raises the greater issue of the choices that can be made – whether to create a more equitable food system or stay with the current dysfunctional mix of hunger and plenty. Analysis by the Food Foundation [3] indicates the pandemic is driving more people into malnutrition and hunger: the food is there, but unaffordable or out of reach.

Yet on the continuity of supply during the pandemic, the food system has adapted. Would the same be true following any global emergency?

The food-feed system is resilient ….. but it could fail catastrophically

The food system supplying Scotland and the UK was able to recover because of particular features of this pandemic. Farming and food stocks in most parts of the world have been little affected so far. With some exceptions, channels for imported food have remained open. It is too soon to say whether more will be restricted if lockdown and social distancing continue, but the chances are they will not be. However, other global crises could have far greater consequences.

Imagine if imports had been shut off. The Food Atlas [4] produced by Nourish Scotland in 2018 shows the country’s reliance on imports. While some food supply chains can be satisfied by local produce, those supplying the staple carbohydrates, plant protein and vegetables are particularly vulnerable.

- Scotland almost entirely relies on imports for staple, healthy carbohydrates. (The UK is less reliant but still has a major deficit.) The main local crops providing carbs are oats and potato, but on current areas they could not ensure sufficiency. Bread in particular – almost none of the bread we eat in Scotland is grown here. Nearly all other cereal carbohydrates are grown outside the UK (pasta, rice). Yet the country’s arable land could grow all the staple carbs needed.

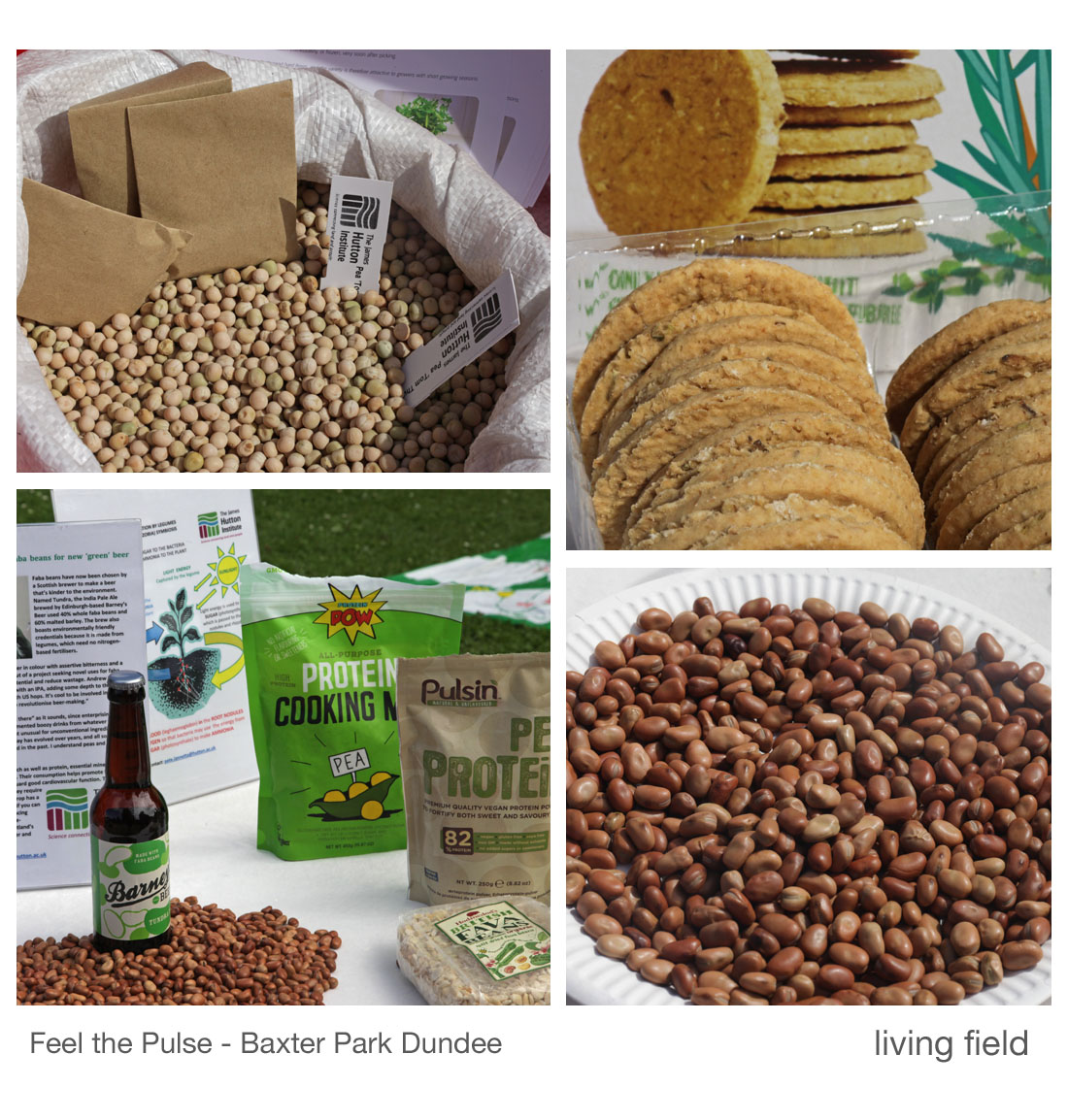

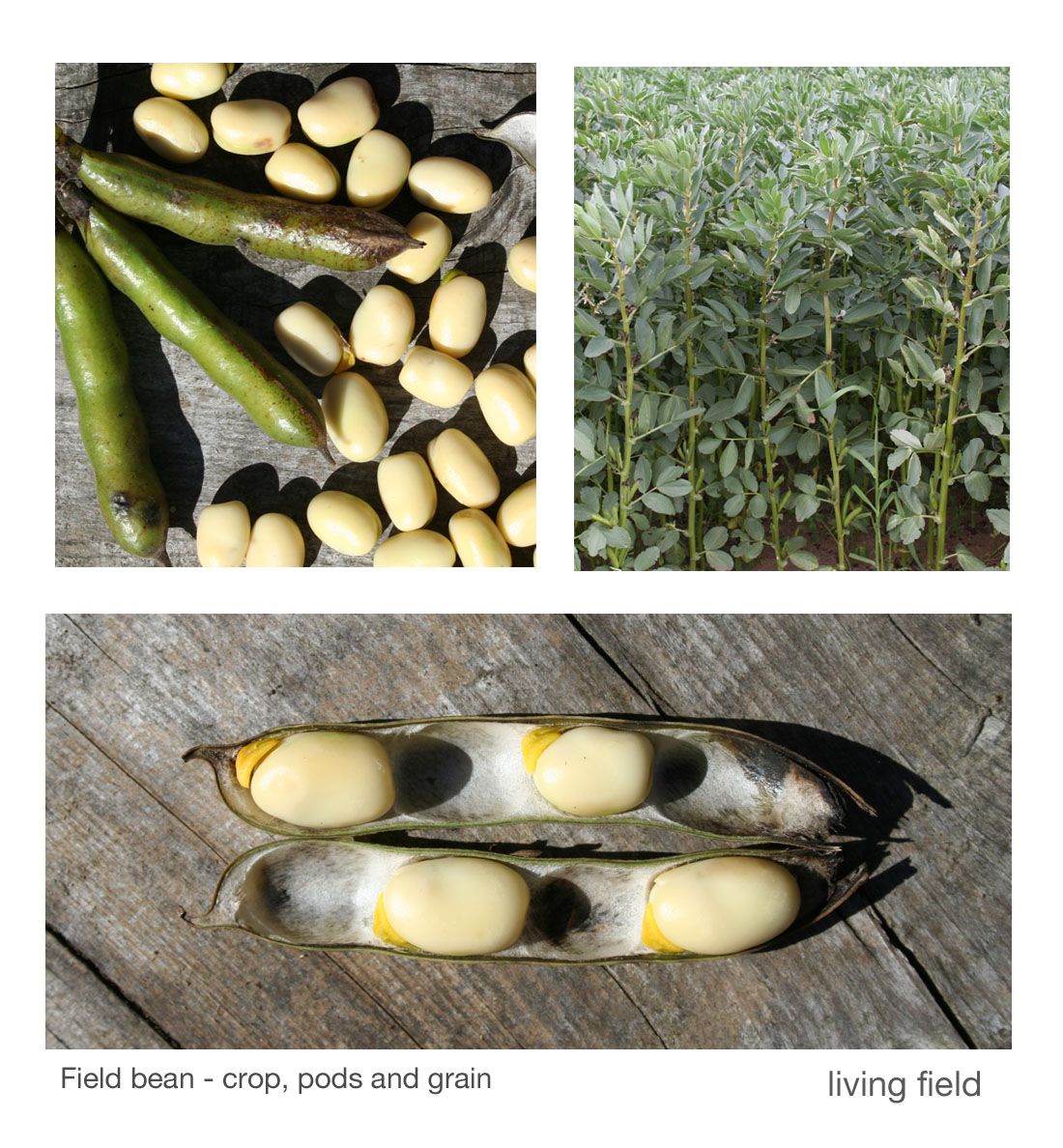

- Pulses – peas and beans – are, with cereal carbohydrate, the staple food of all settled civilisations. As for cereals, most pulse food is imported (e.g. canned baked beans) as is most pulse feed for livestock and farmed fish (e.g. soy bean from the Americas).

- Vegetables – about half the vegetables eaten in Scotland are produced in the UK, most of the rest being grown in the EU or elsewhere.

If imports had been closed down, the country would be in trouble. Could this happen? There are two main possible causes: the food is there but imports are stopped, for example, by blockade due to international hostilities; or the food is not there to buy, because the countries producing it keep it themselves or have suffered a catastrophe in their producing regions (e.g. ash from volcanic eruption). Both have happened in the past. They will happen again.

It’s the balance that preserves

After the food insecurities the 1940s, a post-war Agricultural Expansion Programme was initiated to raise production and shift the balance more towards grain than grass. The programme worked, aided by technological advances in machinery, agronomy and crop yield potential. Yet within a few decades, the country came to export much of its agricultural production and was again dependent on imports for food.

In an uncertain world, a country needs to keep its borders open for trade, both ways. But it also needs to ensure it can feed itself if it has to. The balance needs to be redrawn: local production raised, more food grown than feedstocks for alcohol and livestock, with a shift in emphasis to ‘building’ rather than degrading the agro-ecosystem. All this is possible.

An extended version of this article is published at Food security in the pandemic. More on the food system is available online [7, 8].

Sources, links

[1] Nourish Conference 2019 – Lessons for the Living Field.

[2] Nourish Scotland. Making the food supply chain work for everyone. By Pete Ritchie, 24 March 2020.

[3] The Food Foundation published some recent statistics on 22 May 2020: Food insecurity and debt are the new reality under lockdown.

[4] Nourish Scotland’s Food Atlas: http://www.nourishscotland.org/resources/food-atlas/

[5] To find out more about local food systems, search these organisations:

- Scottish Food Coalition at http://www.foodcoalition.scot/ and their Campaign for a Good Food Nation.

- Food Foundation https://foodfoundation.org.uk/.

- Scotland the Bread at https://scotlandthebread.org/

- City University London, Food Policy: Parsons K, Hawkes C, Wells R. 2019. Brief 2: What is the food system? A Food Policy perspective. In: Rethinking Food Policy: a fresh approach to policy and practice. London: Centre for Food Policy. PDF file available through this link.

[6] Examples of relevant articles on the Living Field web site: City University’s food systems diagram: Five spheres around the food chain. Ten crops from three continents make this simple meal: Beans on Toast revisited. Barley, oats and wheat: Three-grain resilience in Atlantic zone agriculture.

Author/contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook.com