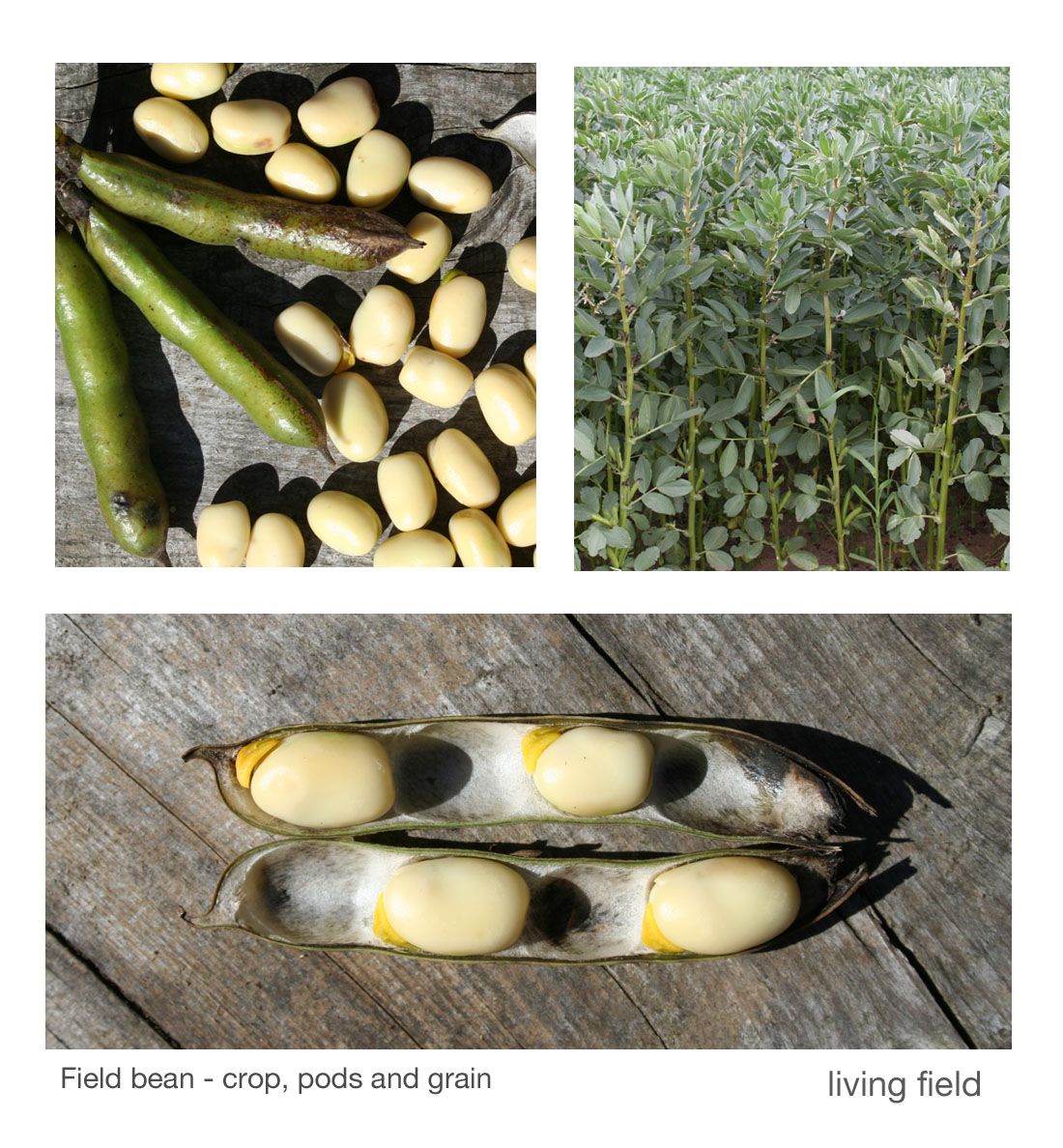

Part of the series on crop diversity. A traditional legume-cereal crop no longer grown in Scotland [*]. Sown as a mixture, grain harvest usually threshed and the mix ground to a flour for food and animal feed. Sometimes harvested green as a fodder. Needs less nitrogen than a cereal alone. Could it be grown economically today as a nutritious, high-value, low-input crop?

[*Update, 26 June 2018: it is still grown in Scotland. See Sources, References below.]

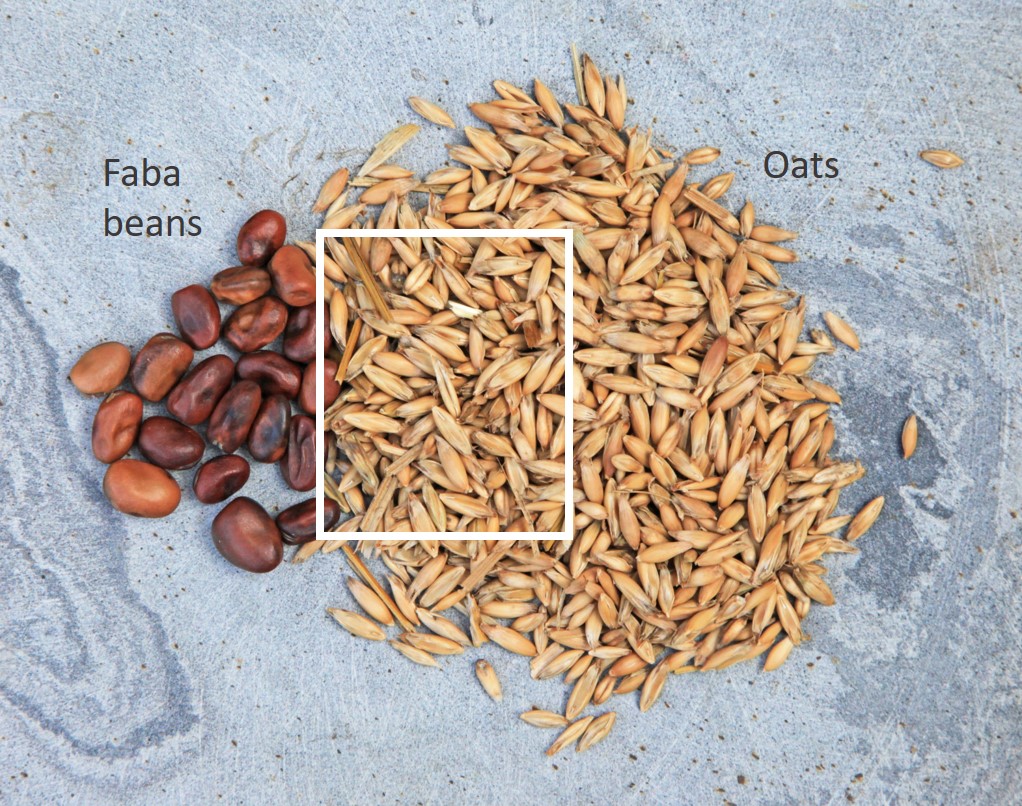

Mashlum is a crop once widely grown, or at least widely known in northern regions. The term has been applied to any kind of crop mixture of cereals and grain legumes (pulses), but was most commonly used in Scotland for a bean-oat or pea-oat mix. The combination is said to provide some stability of yield in bad years, while the meal has a higher protein content than oats alone.

The word, derived from mash (meaning mix), has been reported in Scotland in the form masloche from the 1440s onwards, then from the 1700s as mashlum, and is said to be similar in meaning to the old English meslin and the French mestillon or mesteillon [1, 2, 3].

In most instances, the crop was harvested when both grains were mature, the product then ground into meal. The dry leaf and stem, or straw, was also used for feed, but contained much less protein. It was also grown as a green fodder, the whole crop harvested and again used to feed animals.

Some uses of the word [1] suggest the meal was used to make a type of bread – masloche bread. The Food of the Scots [3] relates that the mixture of oats, barley, rye, peas and beans was cultivated for bread in Dumbartonshire (1794), while several records from diverse parts of the country indicate cultivation of mashlum for the making of pease-bread or bean-bread.

Because of the properties of the cereals used, the bread did not ‘rise’ but remained flat, hence a flatbread. Mashlum flatbread was made by combining the flour of various cereals and pulses then baking it on a hot plate. In one recipe ‘bere meal was mixed with about a third to a quarter of pease or bean meal , and baked with salt and water, but no raising agent, into round cakes about an inch thick’ [3].

Why grow it – the benefits

There are few records of where and how frequently the crop was grown. It existed in various combinations well before the 1700s’ Improvements period and persisted to modern times, still recorded in the census as a distinct crop up to the 1960s. By the later 1800s, it occupied one or two percent of the total area cultivated for grain (see below)

There is little quantitative evidence of its benefits, but they include the following which refer to the bean-oat mix in the later 1800s and early 1900s [2]:

- the bean, a nitrogen-fixing plant, has a higher nitrogen and protein content, providing in many cases a more nutritious food than oats alone;

- the stronger bean plant supports the weaker oat and reduces the chance it will fall over (lodge) in rain and wind;

- the mixture is less prone to reduction in yield or failure in bad years than beans alone;

- while some mineral or organic fertilisers were usually applied early in the crop, the N-fixing ability of the bean means the whole crop needed less added nitrogen fertiliser than oats grown alone;

- it could be used to feed a range of animals – commonly cattle but also horses

- it was an important part of the staple human diet in some regions.

Benefits of the mix as a habitat for farmland plants and animals were unrecorded. Was it high yielding? Again, there are few records, but by the late 1800s and into the 1900s (and converting from yield cited in hundredweight per acre) a good crop was said to yield around 2 tonnes per hectare [2] which is similar to that of cereals at that time. Investigation to date have found no evidence of whether the mix gains an advantage in yield over the two species grown separately.

What were the problems?

Growing two crops in the same area is never straightforward:

- the oats and beans had to be growing in phase, so that one did not dominate or reduce the other, and so that they could be harvested together – the beans were usually slower, so in some places they were sown before the oats, which means two sowing operations in the same field;

- they both had to be of a similar dryness at harvest to be stored for drying together in the field;

- the stronger bean also offered support for birds that fed on the ripening oats.

A highly nutritious crop, therefore, needing less mineral fertiliser – but why was it not a major crop and why did it die out? There are no clear answers, but it probably comes down to the problems in managing two species in the same field and competition from higher-yielding cereals.

After the 1960s, yields of the cereals grown alone began to rise through intensification, which included increasing the dose of mineral nitrogen fertiliser. If the mashlum had been heavily fertilised, the legume would have ceased to fix its own nitrogen.

Mashlum no more!

During the 1940s and up to the 1960s mashlum was important enough to be recorded in the annual agricultural census. In the mid-1940s, it occupied more land than beans alone and than legume forages, but even then, it covered little more than 1.5% of the area of the grain crops combined (oats, barley, wheat, mixed grain and a little rye). By 1960, its area was reduced to 0.2% of that of total cereals. It disappeared from the annual census summaries as an individually reported crop in the 1970s and became part of a general legume-based category of fodder, also including vetches and tares.

The 1980s was a time of great change, notably winter (autumn-sown) crops increasing in area and yield, and during this period, mashlum’s time probably came to an end. It may still be grown in small pockets, like bere barley is in Orkney.

Could it make a comeback?

There is great interest in cereal and legume mixed crops. They need less agrochemical inputs than the same species grown alone. Beans and oats have a higher nutritional value than most common cereals. There would need to be a benefit of growing them together rather than in different strips or parts of the same field and then combining them after harvest.

It might help to plot the future of mashlum if the reasons for its low coverage in the early 1900s and its demise by the 1970s were understood. Simplicity, convenience and economics tend to dictate the shape of farming at any time. Managing two crops, especially if one is faba beans in a variably wet climate, will be problematic until technology overcome issues in harvesting and processing. Public demand for highly nutritious crops relying less on agrochemicals could nevertheless stimulate a revival.

Contact/author: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

Sources, references

[1] Dictionary of the Scots Language. Of the two searchable resources, the word Mashlum appears in the Scottish National Dictionary 1700- at http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/mashlum where it is defined as ‘a mixture of various kinds of grain and legumes such as oats or barley, peas and beans, etc., grown together and ground into meal or flour for baking purposes. In the form mashloche (and related spellings) it appears in the Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue from the 1440s at http://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/mashloche.

[2] O’Brien DG. 1925. The Mashlum Crop. In: Farm Crops, edited by Paterson WM, pages 297-302, published by The Gresham Publishing Company, London.

[3] Fenton A. 2007. The Food of the Scots. Volume 5 in A Compendium of Scottish Ethnology. Edinburgh: John Donald. Mashlum appears in Ch 17 Bread and Ch 14 Field crops.

Additional note: after publishing this article, Douglas Christie from Fife sent a photograph and some notes on his recent and current bean-oat crops. For an update on the story see: Mashlum no more! Not yet.