Ad Gefrin museum and distillery in Wooler, opened March 2023. Life in the Northumbrian kingdoms 6th and 7th centuries. The nearby archaeological site of Yeavering. Importance of soil to archaeological insight. Fine example of local heritage and enterprise combined.

One of an occasional series on museums and botanic gardens.

It is always heartening (the editor writes) to find a local museum established and thriving. The Ad Gefrin museum and distillery at Wooler [1] in Northumberland, together with the archaeological site of Yeavering [2] are a fine example of what can be achieved away from the main centres. Yeavering takes its name from the Celtic Gefrin – the Hill of the Goats, so Ad Gefrin is By the Hill of the Goats [3]. The archaeological site lies several miles north of Wooler.

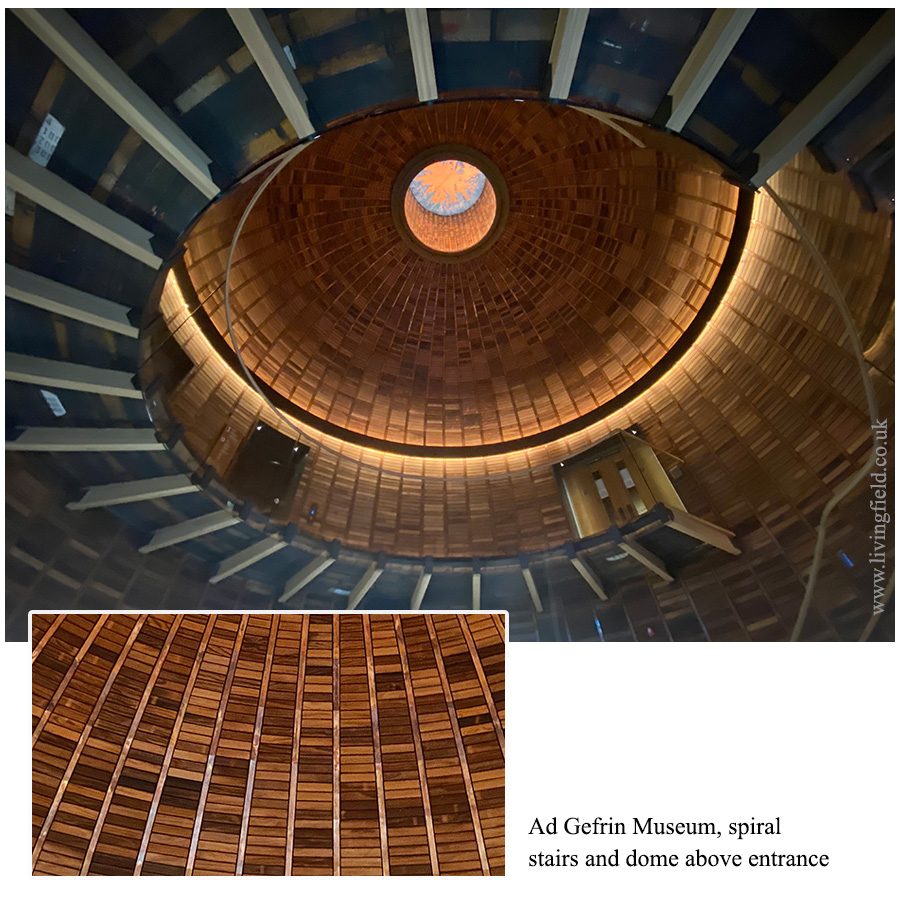

The museum and distillery opened in March 2023. Go through glass doors and immediately the stunning dome of the entrance hall rises above. It was made in the shape of a whisky barrel. The dome is lined by many small, rectangular pieces of pine, sourced from wind-blown timber, each piece prepared and fixed in place by a local craftsman.

The Great Hall

The museum aims to entertain and educate on the Anglo-Saxon, Northumbrian dynasty that governed the region in the 6th and 7th centuries. They established Yeavering from their main base on the coast at Bamburgh. By 700, the site had been deserted, its precise location unknown until rediscovered in the mid-1900s.

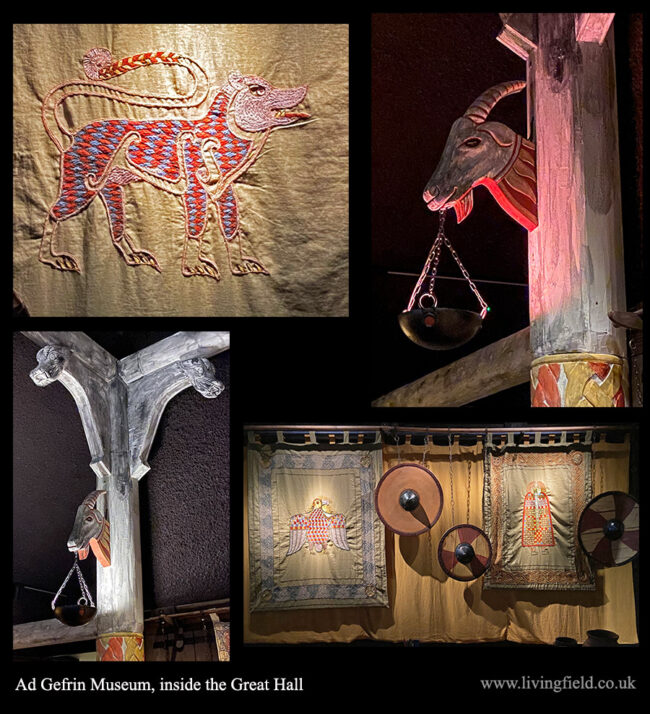

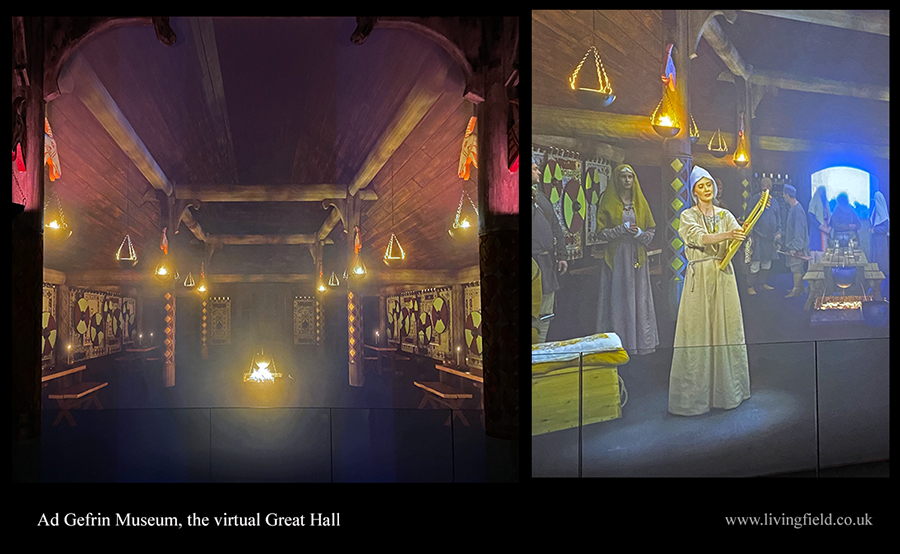

The museum reproduces a central feature of the Yeavering site – a building called the Great Hall. From the museum’s entrance, a spiral stairway (visible in the photograph above) leads to a door into the replica. Visitors can walk around one half of the hall, its walls covered in tapestries and carvings, some shown on this page. The other half is virtual, viewed through a screen and letting the viewer appreciate the full length and interior design of the building.

Linger for a few minutes and the virtual half comes alive as people appear, tell stories and sing of the kings and the life at that time. It’s an ingenious way of drawing peope in, making them feel almost as if they were there.

The museum displays some of the objects found during archaeological digs at Yeavering and models of some of the buildings including the Great Hall and a tiered Grandstand.

Yeavering archaeological site

The site was revealed through examination of crop marks on an aerial survey of the region in the dry summer of 1949. It was first excavated from 1953 to 1962 and the results published 1977 in an authoritative report by Brian Hope-Taylor, available today as a free download [4]. The report and its author have been widely praised [5]. It remains an engaging and impressive read, and not only for archaeologists. Enquirers from any discipline will appreciate the logical approach and the analysis of uncertainty in reaching conclusions from limited data, especially on the structure and functioning of different buildings and enclosures. The report repeatedly stresses the importance of soil to archaeological method (see below).

The site lies on an area of flattish land, known as the whaleback, the northern side descending steeply to the River Glen and the southern rising to the hills of Yeavering Bell. The River Glen joins the River Till which then feeds into the Tweed. Much evidence of occupation and farming since the neolithic have been found in this area. A large Iron Age hill ‘fort’ and many dwellings were built at the top of Yeavering Bell and the lower land around the Rivers Glen, Till and Tweed is dense with pre-historic settlement and signs of farming.

Archaeological studies at the site have continued and were active in summer 2023, but by October the exposed surface had been recovered with soil to protect it over the winter.

Soil – AgriculturE – food

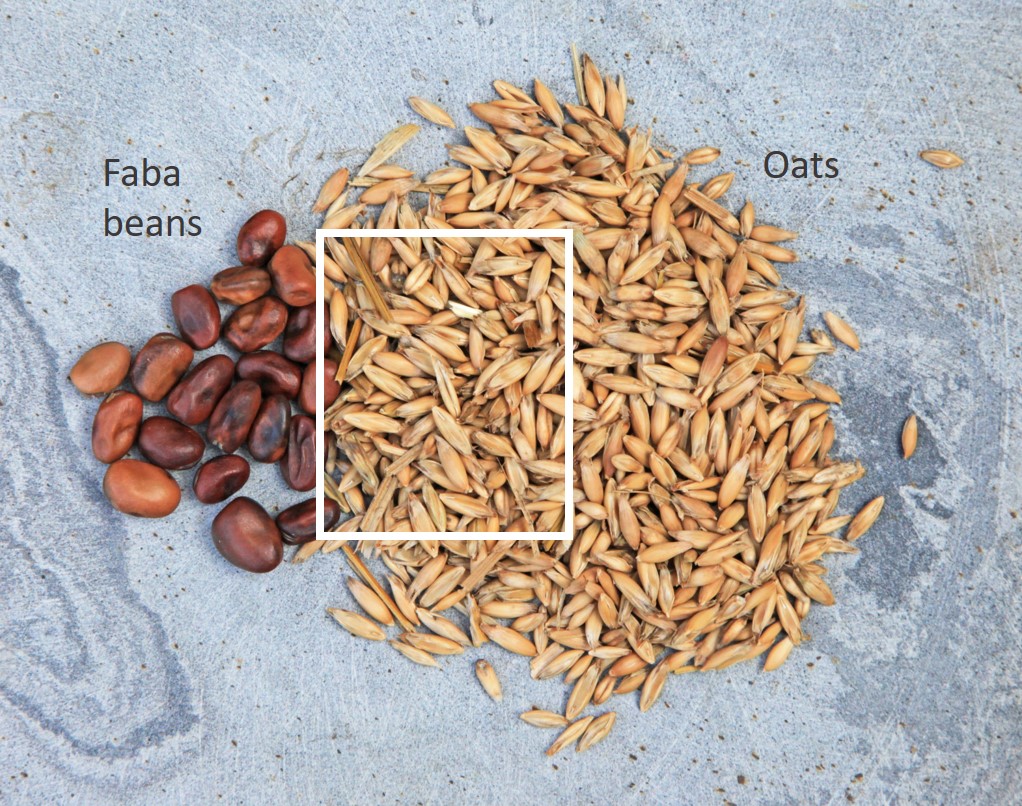

The main agricultural land use around Yeavering today is grazing for livestock, both sheep and cattle. Grain has been grown in this area. One of the boards in the museum states that rye, barley, wheat and oats have always grown well in the Millfield Basin – an extensive area of fertile land to the east of the Yeavering site. And the crop marks that reveaed the outline of the buildings were first seen when oats covered the land in 1949.

Of interest to Living Field readers may be the importance of soil condition, both in locating the structures initially and then photographing their exposed outlines. Cropmarks are ‘negative structures’ differing from the surrounding soil in the the type of soil that filled the space when the original structures rotted or were removed [4]. If topsoil fell into the spaces, it would probably have contained more organic matter than the surrounding subsoil, and hence have a greater capacity to hold water.

Plants growing in this deeper, more organic material may absorb and reflect a different amount or a different quality of incoming solar radiation. Especially in a dry year, plants here remain greener and unwithered for longer into the summer.

The excavations also reveal the extent to which human habitation and farming influence the erodability of soil, its movement across and out of the area, leading to variation in depth. ‘Centuries of ploughing’ had eroded topsoil from the crest of the site and repositioned it towards the edges. The archaeologists could even tell whether a sub-soil had been previously cultivated or not by its feel and sound when turned with a trowel [4].

LIVESTOCK

Many animal bones and bone-fragments were found at the site. Analysis by ES Higgs and M Jarman [4, 6] showed cattle were by far the predominant livestock rather than sheep, pig or goat. Yet it’s the age when the catttle were killed that tells us something of the pressures on livestock farming at that time, pressures not much different from what they are today.

Livestock need to be fed through the winter to keep them alive. Living grass may prove insufficient, so the herd is sustained with stored hay or grain. Breeding cows that perpetuate the herd have to be prioritised to ensure they survive. But what of the general cattle if feed is likely to run out.

Higgs and Jarman propose that cattle were killed early in their growth cycle, well before they reached full size. The collection of bones indicate age at death had two peaks – 6-11 months and 24-30 months. The first group, born in late spring and early summer, were killed over the following winter, presumably to leave enough feed for the rest of the herd. The second group were fed through the first winter, then a second, before being killed. The relatively short life-span of the cattle points to the pressure on farming to balance size of the herd, winter feed and the need for food.

Today, overwintering cattle, whether kept indoors or on grass, have their food supplemented by grain or silage, possible with concentrates, sourceable from a range of local and international supply chains. At Yeavering, they had only what they could produce and save from local fields.

The future

The Yeavering / Ad Gefrin site is now managed by the Gefrin Trust [2]. The following is extracted from their web site – “In 2002 Ad Gefrin, the physical site and the ongoing story, passed into the hands of The Gefrin Trust. Our aim is to preserve, investigate and recount the history and impact of this important site in the north Cheviot hills, from prehistory right up to the latest investigations and finds.” The Trust’s web offers several free downloadable publications on the region’s history and archaeology.

Archaeological studies continue at the site [8].

Sources | Links

[1] Ad Gefrin Museum and distillery, Wooler: https://adgefrin.co.uk/

[2] Yeavering archaeological site: The Gefrin Trust describes the continuing excavations and offers several free downloadable publications on the history and archaeology of the region. See also Canmore – Excavations at Yeavering Bell.

[3] The goats in the name have been around for millenia. They were once farmed, then went feral and now form a wild landrace of the British Primitive Goat. They are declining and under threat of extinction: Northumberland National Park; British Primitive Goat Research Group.

[4] Hope-Taylor, B (1977) Yeavering – an Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage. Report with many figures and plates downloadable at the Archaeology Data Service; and the Gefrin Trust.

[5] More on Hope-Taylor at: Thomas, S (2013) Public Archaeology 12, 101-116; Bamburgh Research Project 2011 The legacy of Dr Brian Hope Taylor.

[6] ES Higgs and M Jarman: the report [4] gives no information on the people who analysed the animal bones from Yeavering. Higgs and Jarman were well-known archaeological pioneers and scholars who made major contributions to studies of the past e.g., Higgs, E. S. and Jarman, M. (1975) Palaeoeconomy. In E. S. Higgs and M. Jarman (eds.) Palaeoeconomy, 1-7. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

[7] For more on the analysis and meaning of animal bones in archaeology, see this online publication: Baker P, Worley F (2019) Animal Bones and Archaeology – Recovery to Archive. Historic England Handbooks for Archaeology.

[8] Durham University: Yeavering | A palace in its landscape | Research Agenda 2020.