From mediaeval wall paintings (murals) about 1250 at St Agatha’s, Easby, Yorkshire …. from the Labours of the Months …..

Author: gs

ScoFu: the quest for an indigenous Scottish Tofu

Chantel Davies writes:

As a long-time vegetarian and fan of Asian food, particularly tofu, in recent years I have limited my consumption of soya due to the sustainability issues of soya production and potential negative impacts on health.

Beginnings

My inspiration grew from a Japanese anime series, ‘Yakitate!! Ja-pan’ (i.e ‘Freshly Baked!! Ja-pan’), which follows the adventures of the young protagonist, Kazuma Azuma, as he follows his passion to invent an authentic Japanese bread of which the Japanese people can be proud. In a similar vein, I have embarked on a quest to produce an authentic Scottish tofu, using local ingredients and some gastronomic daring.

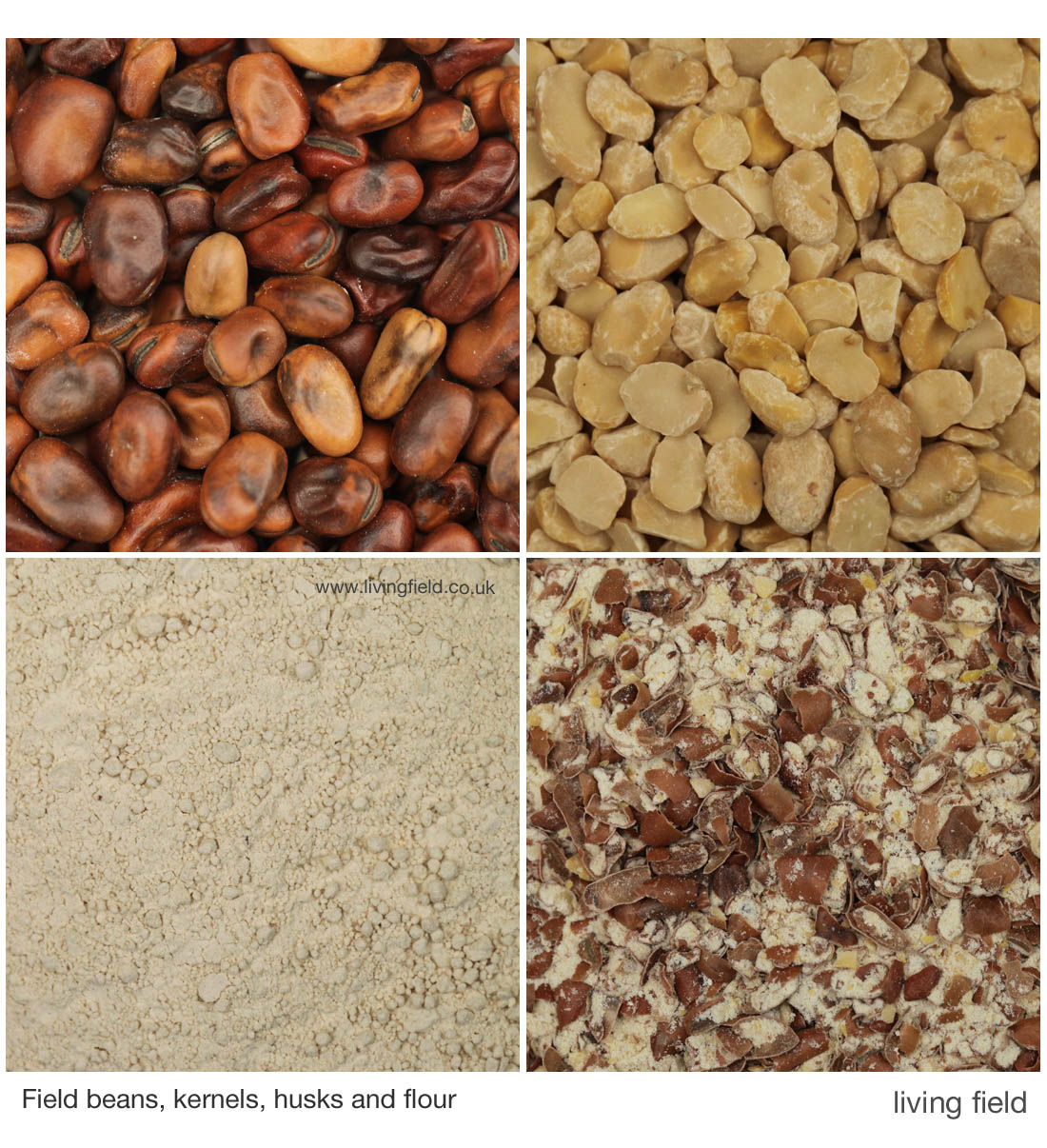

I acquired some faba bean powder (flour) from the Institute’s Pete Iannetta, who is growing beans in experimental fields at the Dundee site (and using them to create new bean-based products including craft beers).

My first experiment, ScoFu No. 1, was to test the production method and make some technical adjustments. It was marginally successful, but the quantity of final product after pressing resembled a crêpe with a lot of left-over okara (bean pulp). Not really what I was aiming for, though the okara could be used for faba bean falafel – an experiment I will save for another time.

ScoFu No. 2

For ScoFu No. 2, I increased the quantity of ingredients and modified the processes. Firstly, I produced the purée. After a bit of culinary alchemy, and a handy little tofu box, I managed to produce a very neat-looking block of tofu (image below).

After a little more magical waving and muttering, the tofu became a delight of pan-fried strips, infused with chilli and garlic, served with spicy rice and a dash of soy sauce. The texture, although soft and crumbly, held together nicely when cutting and cooking.

The flavour was definitely faba bean, with a hint of bitterness due to the preparation method (and maybe the coagulant), but also a touch of umami; beany flavours are often preferred in East Asia. On a firmness scale of 1 to 5, with five being very firm, I would put this at 3.5, or ‘momen-dofu’ as the Japanese would say.

A rather delicious stock was produced in the formation of curds, which could form the base of type of miso soup, or vegetable stock.

Whilst this has been a success, there are so many different variables to consider when making tofu that can influence taste, texture and firmness that I feel my adventure has only just begun. Onward to ScoFu No.3!

Contacts, sources, links

Chantel Davies email: chantel.davies@hutton.ac.uk; c.davies@growing-research.com

The beans used to make the Scofu are locally grown faba beans Vicia faba.

Also on the Living Field web:

Feel the Pulse – our exhibition on beans at Baxter Park with Dundee Science Centre and Legumes in the Living Field garden.

Related: SoScotchBonnet – our search for the truly indigenous crop.

[Published 27 June 2017; updated with new images 21 July]

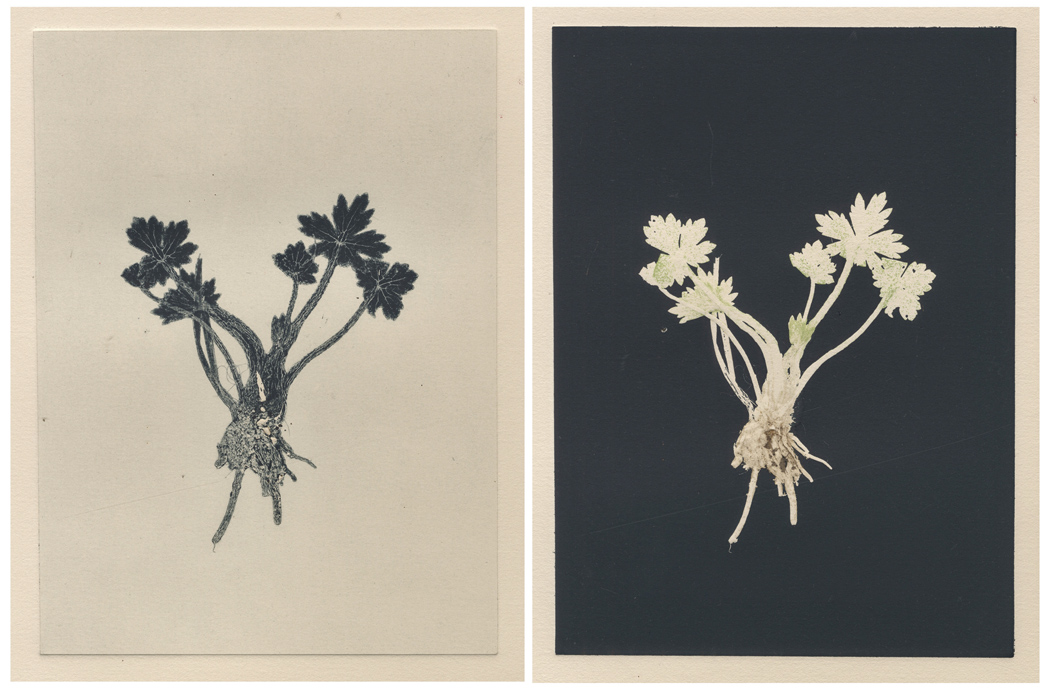

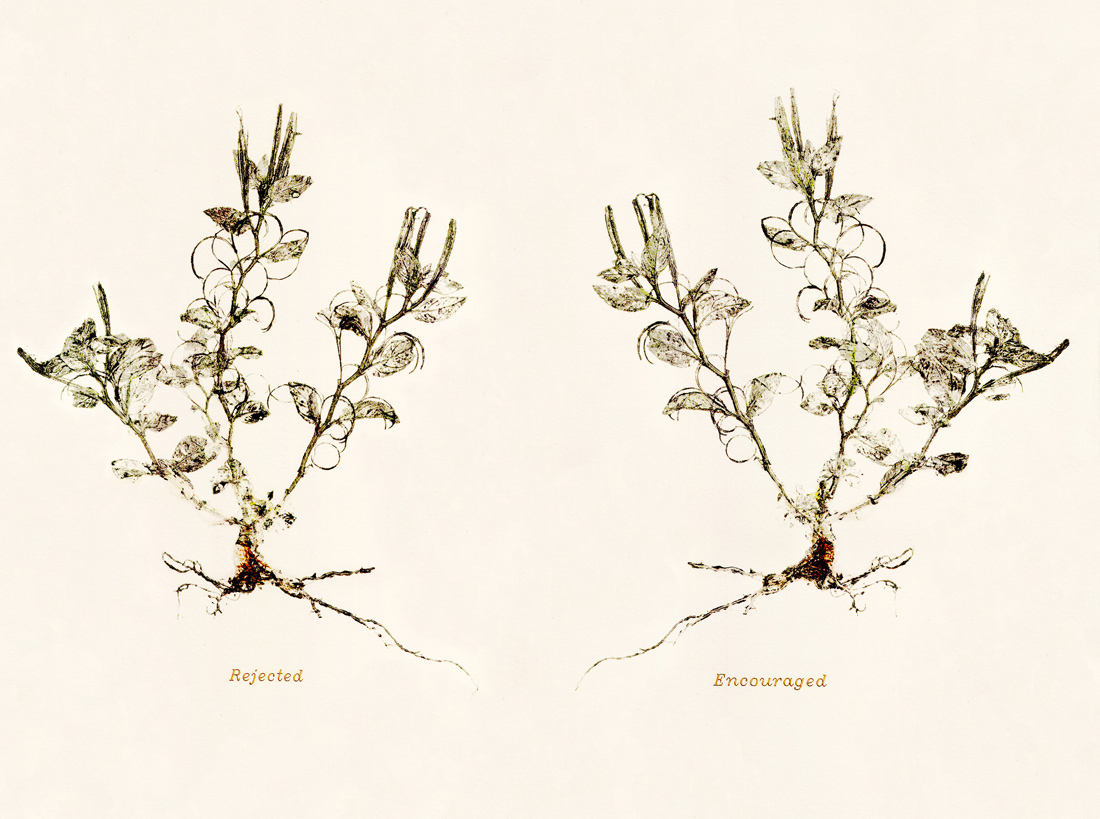

Tina Scopa Edaphic Plant Artist

This year, as a 3rd year Contemporary Art Practice student at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design (Djcad), Dundee and with the support and encouragement of Geoff Squire & Gladys Wright (& Pete Iannetta who pointed me in the right direction) I was introduced to the Living Field at the James Hutton Institute, Invergowrie and ran my plant-printing workshop as part of the Open Farm Sunday event.

My work concerns wild plants (and those often considered to be weeds) and the soil in which they grow. I currently work mostly in printing where I have developed a number of plant printing techniques. I also make ‘earth’ paintings, and work in ceramics, photography, and laser cutting. I would be very interested to hear from any scientists who might be interested in this work, have comments, or who might want to collaborate with me, particularly in context of the blue pigment; in making the prints lightfast; or the possibility of employing these printing techniques as a scientific tool.

Edaphic Plant Art

In my most recent work I coined the term, Edaphic Plant Art. This body of work was concerned with a small patch of grass on campus. I was interested in the variety of wild plants growing on this patch and also in the soil in which they were growing. I focused on 5 plant varieties and attended soil science lectures. I documented these plants by using 3 different plant-printing techniques that I have termed, the Pigment Print; the Graphite Print; and the Ink Print.

These prints were presented on the wall in a grid format together with digital print photographs of the plants. Porcelain tiles were also prepared for each plant. In addition ‘earth paintings’ were made using soil taken from the site and ‘healthier’ soil taken from another site. Besides each painting a soil sample was presented in a hand made porcelain cup.

Weeds

This body of work began with the initial desire to get plants to ‘draw’ themselves. The plants used were those largely considered to be ‘weeds’. The method used to develop this idea has primarily been experimental printing. Experimental photography techniques were also been employed to a lesser extent, as were small sculptural works.

Through the process of experimentation and subsequent development the goal was considered to have been accomplished.

Through the process of experimentation and subsequent development the goal was considered to have been accomplished.

The resulting plant ‘drawings’ were able to convey the inherent beauty of these weed forms and the individual ‘character’ of each plant. In addition, the body of work was presented as a metaphor for our own human condition, commenting on different aspects of ourselves.

The Blue Pigment

Over the course of developing my Pigment Prints I have often noticed a very blue pigment located just where the stem meets the roots in certain grasses. If anyone can shed light on this I would be very grateful and would love to extract this in the lab.

More from Tina to follow ….

Contact

http://tinascopa.wixsite.com/website

The Garden at Open Farm Sunday 2017

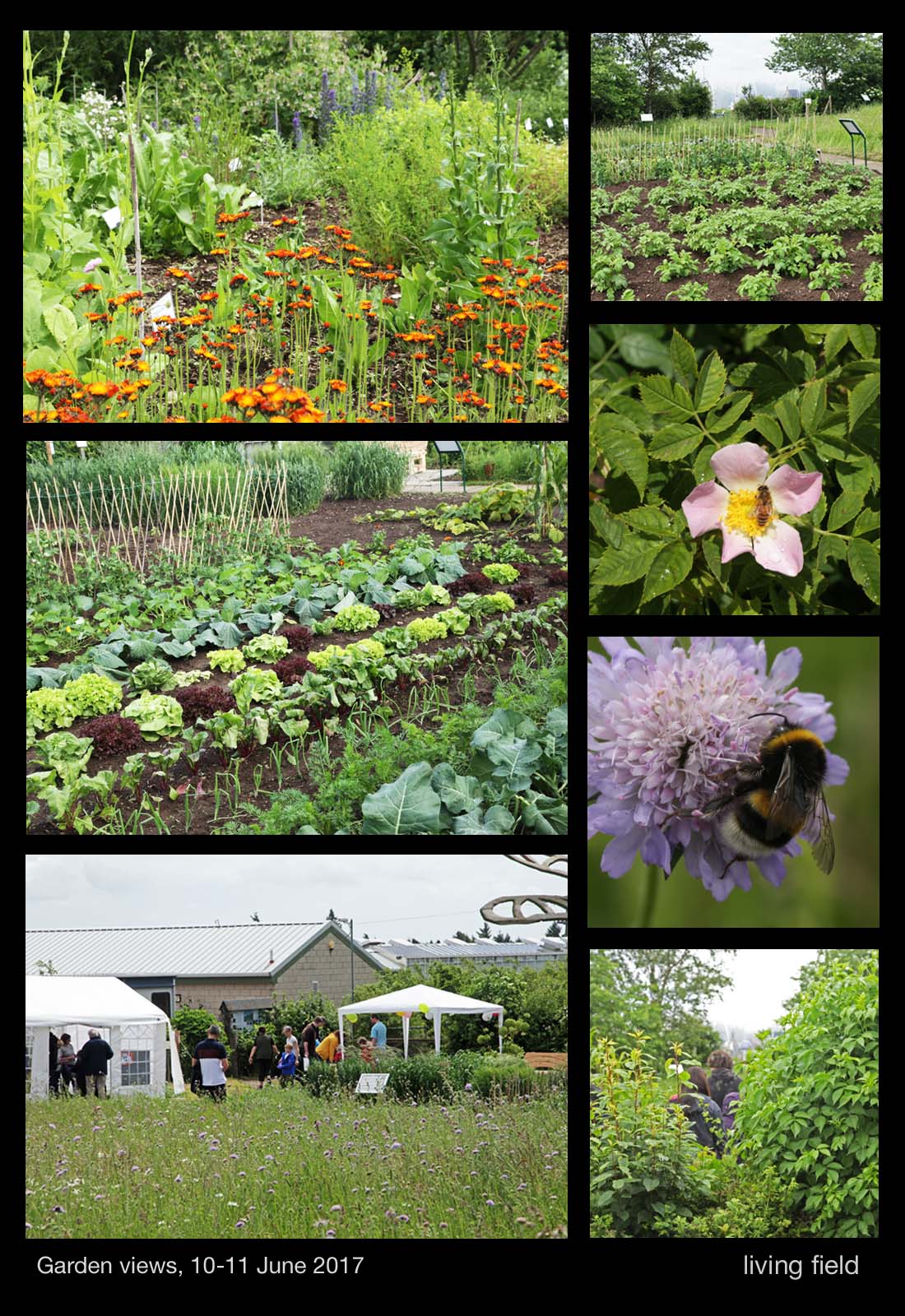

The Living Field Garden was looking good at Open Farm Sunday on 11 June this year. Despite wet weather, we had over 1000 visitors.

More on the Open Farm exhibits appears at the Hutton Institute’s LEAF web pages. Here we look at some of this year’s plants.

The hedges are thick with leaf, the hawthorn now filling its haws, the elder and the wild rose still in full flower. Water forget-me-not and wild iris are flowering in the wet ditch, while field scabious, comfrey and viper’s bugloss are offering plenty for the several species of bumble bees that live in and around the garden.

The east garden’s perennial and arable beds

The three local species in the images above all reside in their own habitats, but are within a few seconds of hoverfly flight to the exotic maize in the arable plot. Maize originated as a crop in the Americas and was unknown in the country before the last few hundred years.

This proximity of the wild and the cultivated is one of the recurring features of the garden. The images above contrast the cropped area of the east garden with the perennial meadow and hedge plants. The field scabious in the meadow will keep the bees well supplied until late September at least.

Raised beds of the west garden

Through the gate, the west garden’s raised beds are filled this year with vegetables and herbs. There are various cabbages and spinaches, parsley, thyme and dill, companion plantings and intercrops, to name a few, and all are intended to show the very different concentrations of minerals that these plants take from the soil and accumulate in their tops.

The background and results of this study, which is based on research at the Institute, will be covered in a future Living Field post.

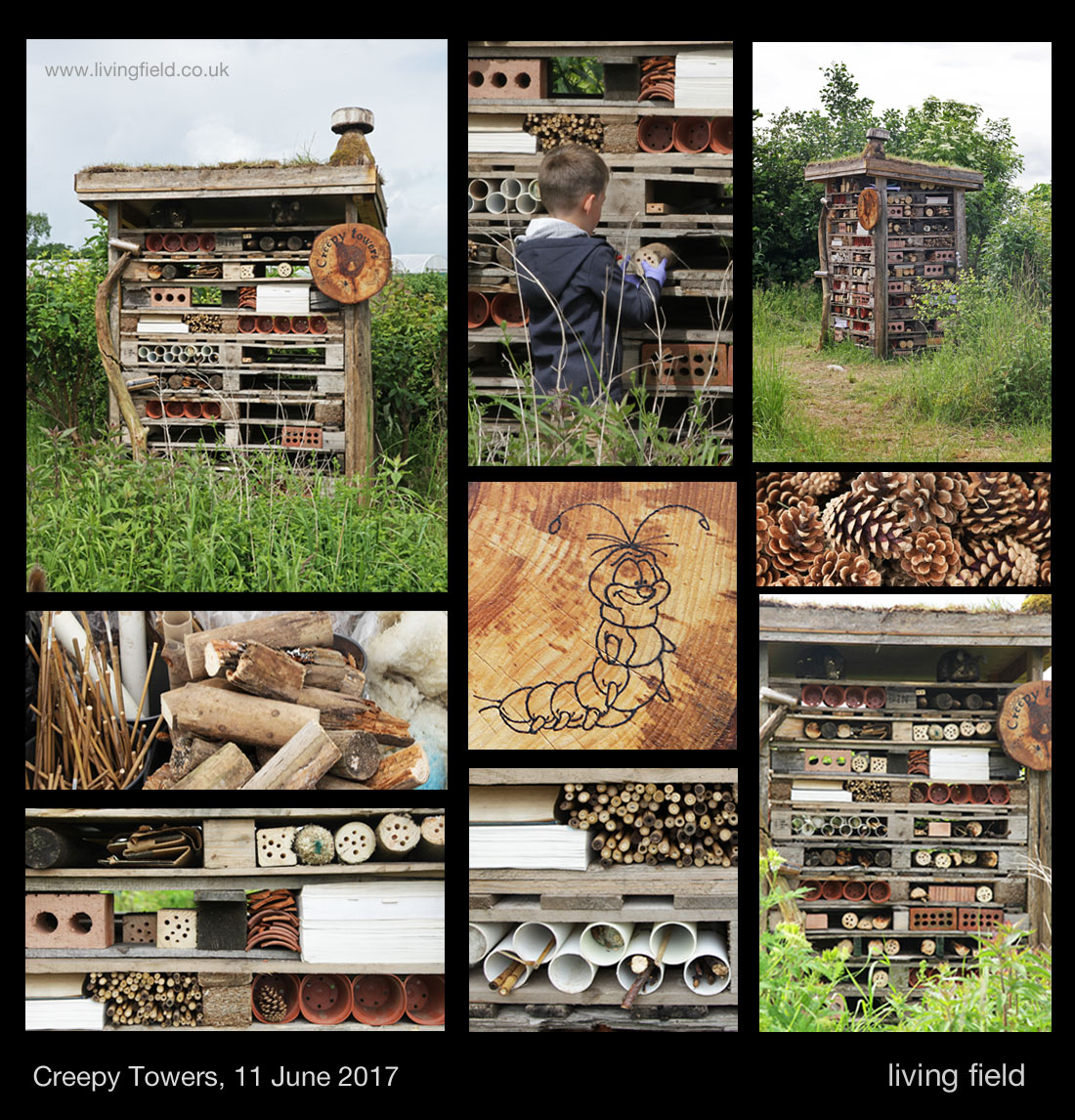

Creepy towers

We’ve been constructing various small places for insects and spiders since the garden began, but this year, the idea of a more permanent residents block was made real just before Open Farm Sunday. First stack your pallets, add a roof of turf and fill the spaces with small bespoke homes for our creepy friends.

Old logs and fence posts, with holes drilled in the ends, pine cones, garden canes, bricks with holes through, tubes, sticks, bits of rotting wood – all make ideal residences.

Exhibits at Open Farm Sunday 11 June 2017

The garden made a return this year as the base for many activities at Open Farm. The cabins hosted exhibits on greenhouse gas emissions and nitrogen fixing legumes. The east garden, as you go in through the gate by the cabins, had a soil pit, cereal-legume intercropping, pest traps and the urban bug house shown above, while the west section displayed heathy vegetables, soil bacteria, our friends from Dundee Astronomical Society and Tina Scopa running a workshop on wild plant ‘pressing’.

The garden was maintained by the usual crew: Gladys Wright and Jackie Thompson on the arable plots and raised beds; Paul Heffel from the farm kept the hedges in trim and cultivated the soil where required; Geoff Squire arranged the medicinals and dyes and kept an eye on various rarities and curiosities.

Gill and Lauren Banks, with help from the farm, constructed Creepy Towers, for which the ‘chimney’ was crafted by Dave Roberts and the plaque by visiting student Camille Rousset.

There is no formal funding for maintaining the garden – it happens through commitment and hard work, often out of hours.

Contact for the garden: gladys.wright@hutton.ac.uk

Burnt whin

The very dry spring of 2017 not only set back crops but prepared moor and rough grazing for fire. These habitats are used to fire. They have evolved with it as a recurrent destroyer, at least since the last ice retreated and people returned in numbers to begin clearing and cultivation.

The problem for those today concerned about natural heritage is that fire does not discriminate, and while the burning of grass and whin (or gorse) Ulex europaeus will not affect their survival in most localities, it can devastate rare and declining, or even newly expanding, populations of other plants growing along with them.

This was the case in pockets of whin-dominated land that were fired during the dry spring. Fire left the whin’s stems and branches like blackened bones. They appear intact, but they disintegrate to powder if you try to pick them up.

The intensity of the fire was so great in places that everything had been burned, but at the edges not all was lost. Flowering branches had been singed in the heat, no longer bright yellow, but perhaps not dead; and some small broadleaf trees such as rowan Sorbus aucuparia had one side singed and the other not.

So what made an ‘edge’ that stopped the fire. In one area, it was a narrow road that the fire did not cross. In another it was wetter ground in a hollow that stopped the advance. (It takes a lot to completely dry out a bog in these parts.)

The images above (top) show a wet hollow or depression, which stopped the fire from consuming the willows in the middle ground but not the rough grass before nor the trees beyond.

The fire also failed to take some small areas. One (lower left above) appears to be nothing other than a small pile of droppings (deer?) which presumably was wet enough to prevent the surrounding grass for being blackened.

Threatened juniper

This small fire, covering just a couple of acres (not quite a hectare) would have destroyed any birds’ nests in its way, but it also destroyed juniper and young pine.

Juniper Juniperus communis is particularly vulnerable in many areas of Scotland because it is declining due to a range of factors including over-grazing and disease [1, 2]. The location shown in the photographs, within 10 miles of Inverness, falls within Zone 1, that of least concern for juniper conservation.

Yet here, even in Zone 1, within an extent of 5 x 5 km (25 square kilometres) juniper exists mainly as isolated mature bushes and some regenerating young plants, not as a complete stand.

It is heartening to see several young plants in this area [3], but not to see that in this one small fire, some young juniper were scorched to death.

There was evidence that the fire was more intense under and around some juniper (top left above), perhaps because the dead plant matter accumulating under the bushes was more flammable than the surrounding grass? Perhaps there were other reasons.

Also young Scots pine Pinus sylvestris were badly affected. The one top right above was 100 metres from the nearest tall mature native pine tree; and though it looks small, it could well be several decades old, checked in growth by the poor conditions. It’s a pioneer spreading from a native remnant, but not likely to survive this fire.

This was a very small bush fire by local standards, and insignificant compared to the fires raging over thousands of square kilometres in some parts of the world, but even so it caused a lot of damage to populations of juniper and Scots pine that are struggling to maintain or expand their range.

It may add to the demise of juniper in this region. The fire was probably started illegally by someone.

Links

[1] Forestry Commission Scotland. Conservation zones for Juniper. The locality shown in the photographs above is in Zone 1 (self-sustaining juniper populations – conservation management beneficial in some places to promote natural regeneration). See also Species action notes which consider juniper along with black grouse, capercaillie, red squirrel, pearl-bordered fritillary and chequered skipper.

[2] Forestry Commission Scotland. Planting juniper in Scotland: reducing the risk from Phytophthera austrocedrae. Link to Online Guidance.

[3] Scotland’s Nature (Scottish Natural Heritage). Good news for Scotland’s juniper.

Contact/author/images: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

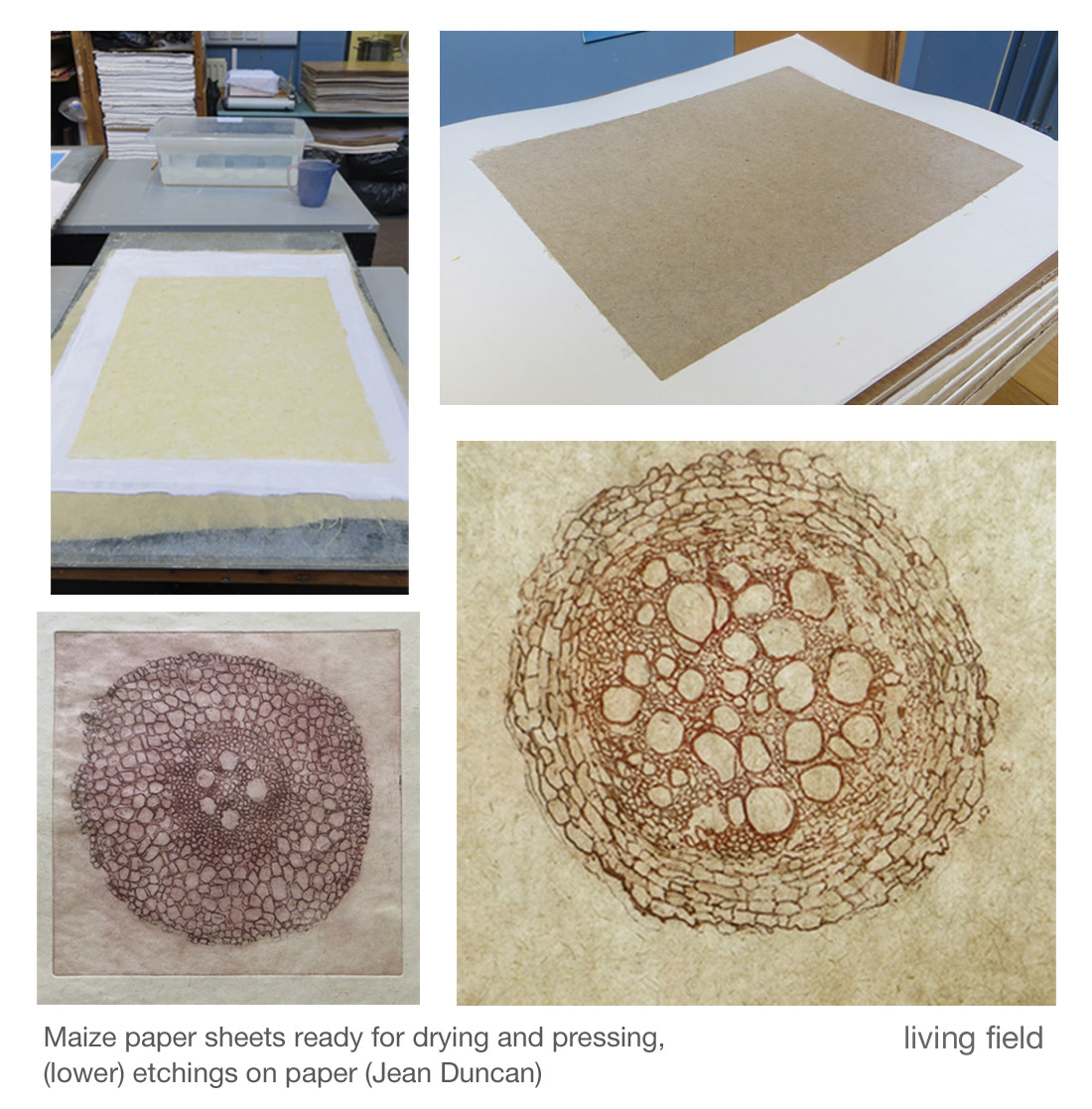

Maize paper

Most of our paper comes from plants, but the process by which leaves and stems are converted to sheets that we can write on or wrap things in is unknown to most of us.

As part of her work with the Living Field, Jean Duncan has been making paper from plants grown in the garden.

She started with some maize, which is a tropical and sub-tropical species originally from the Americas. Some types can now grow in our climate, and it was one of these that was grown in the garden for its cobs (corn on the cob).

Jean used the maize plants to make the paper. Here is a description of what she did.

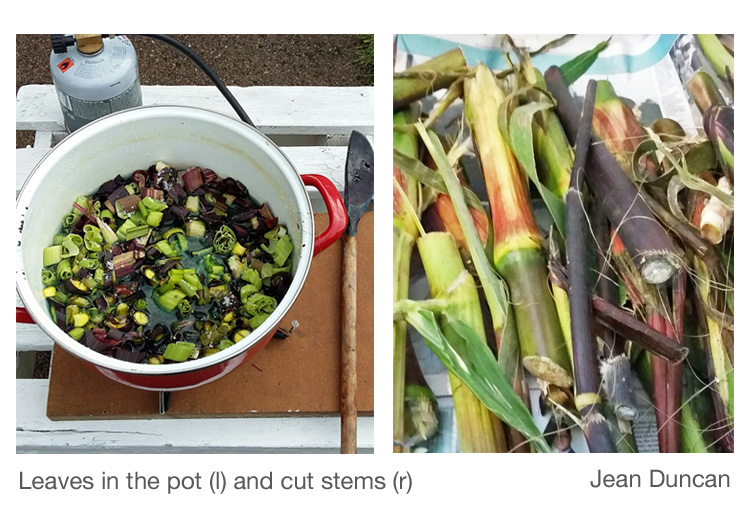

Step 1 is to collect maize leaves and stems when they are in good condition, still green.

Step 2 is to cut the leaves and stems into small pieces. Leaf pieces should be about the size of those in the white bowl. The tough stems were cut into larger pieces (right below).

Step 3 – put the cut material into an enamel bowl or pot (above left). Add soda ash to the material, 1 teaspoon for a 10 litre pot, and mix.

Step 4 – cook the plants for 3 hours, or more if the material is tough. At this point you will need pH indicator strips (litmus paper) to check that the cooking is going according to plan. (Litmus can be bought on-line or at some gardening shops.) The pH of the mixture should be around 8, but if it drops to 7 or 6 then add a little more soda ash. When cooked, the fibre should be soft and easy to tear.

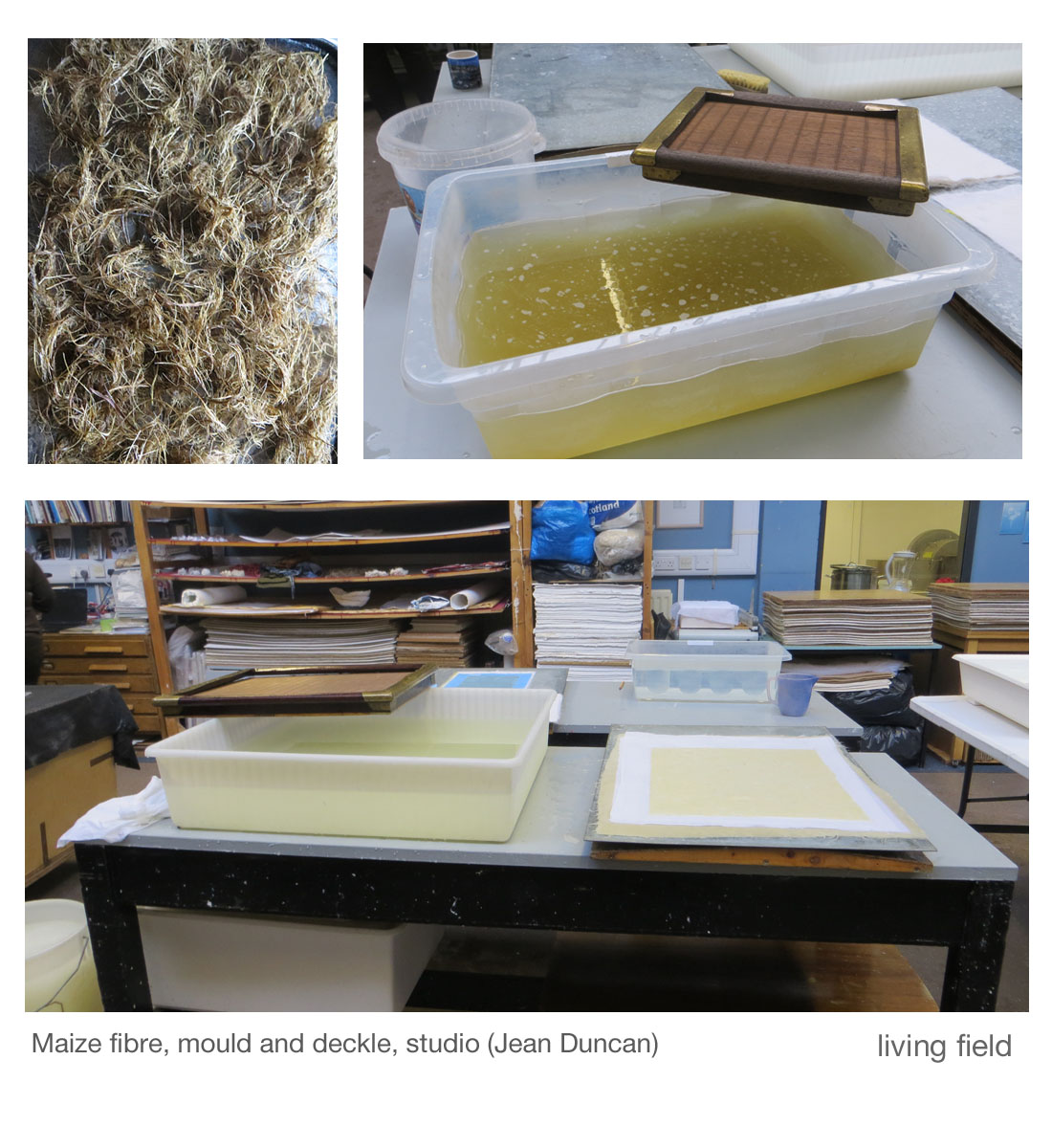

Step 5 – rinse the fibre thoroughly in water; when fully rinsed the pH or the water should be neutral (i.e. about 7).

Step 6 – the fibre now needs to be beaten to a pulp. The traditional way is to beat it with a mallet for a few hours. (Craft-workers in some countries still use this method). An alternative, if you have electricity, is a kitchen blender working in short bursts so as not to burn out the motor. Jean uses a machine called a Hollander beater.

Step 7 – the fibres are now ready to be transformed into sheets of paper. The pulp is suspended in water. A ‘mould and deckle’ is lowered into the water (image above) and brought out slowly with a flat layer of fibre on it, or else the pulp is poured into the mould and deckle until there is a flat layer of the right thickness for the type of pulp (which you work out by trial and error); the water drains out through holes leaving the moist fibre.

Step 8 – the moist sheet of fibre is turned onto an absorbent fabric or board or something similar for drying and pressing, a procedure that takes about 3 days (top right in images below).

And that’s it – a sheet of paper!

Info, links

Khadi papers India. Web site: khadi.com. Youtube: Papermaking at Khadi Papers India

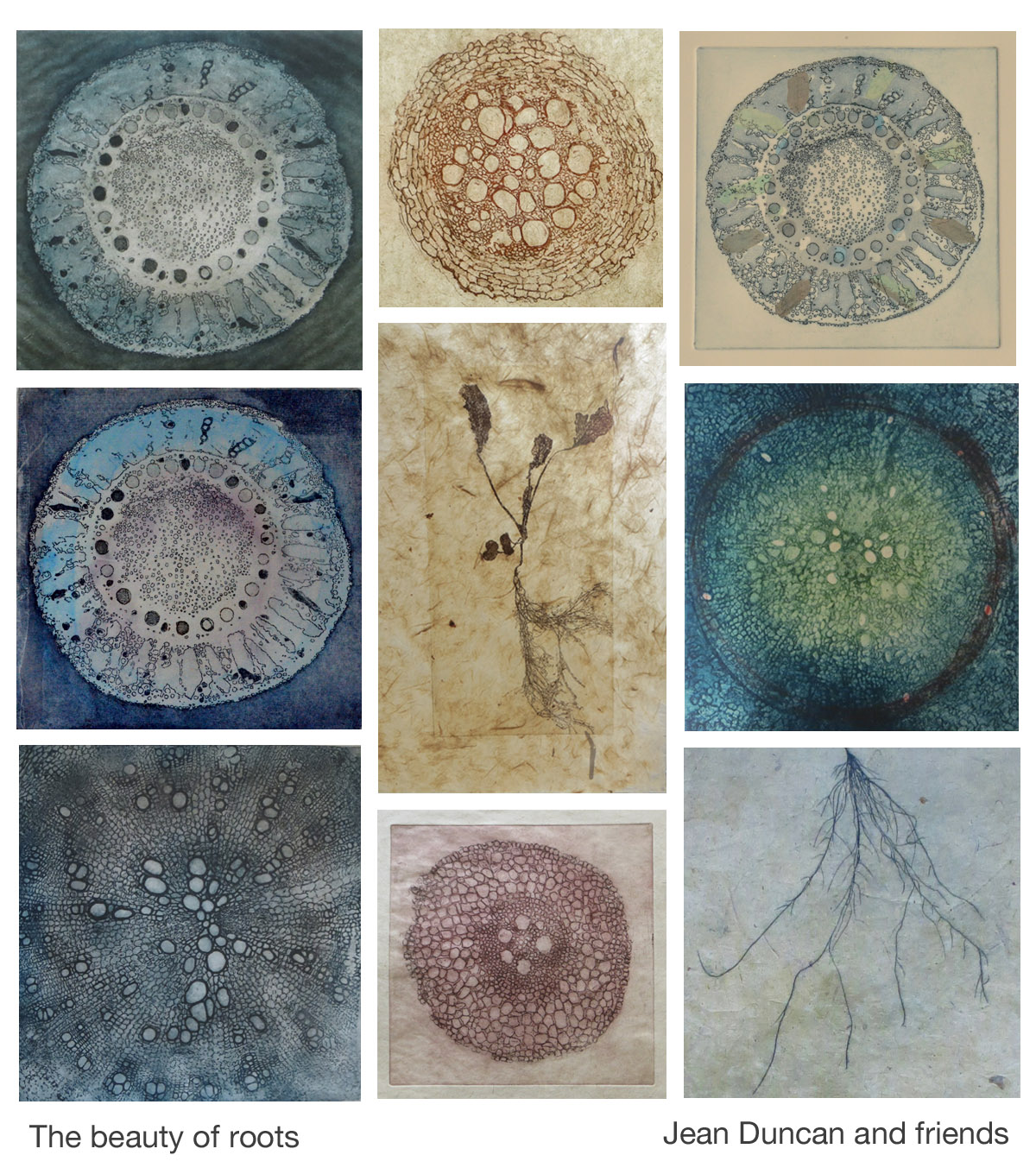

Jean’s recent work on an exhibition of etchings using her own-made paper: The Beauty of Roots and Root art.

[Update with minor amendments 10 June and 27 July 2017]

The Moon in March

With thanks to Ken Kennedy of the Dundee Astronomical Society … more from Ken on Noctilucent Clouds.

The phenomenon of noctilucent clouds

Dundee Astronomical Society has been joining us at various open days for some years and has a small observatory in the Living Field garden. Ken Kennedy kindly sent us this article on noctilucent clouds for the Living Field web site.

We all hope for a fair bit of sunshine during our northerly summer months but the suggestion that clouds may appear in the summer sky will not be a concept too alien to most of us. However, the clouds I am thinking about are not the cumulous or even stratus type clouds you may well expect on many (well, perhaps most) summer days. In fact these clouds will not be making their appearance during any summer day but could appear an hour or so after the Sun has set and disappear about an hour before sunrise.

On June 8, 1885 Thomas Backhouse in Kissingen, Germany became aware of wispy bluish-white clouds low down towards the north and north-west following a beautiful sunset just a bit earlier in the evening. It had become quite a habit for many people to watch the sunsets and sunrises following the eruption of Krakatoa in August 1883. Many of these were quite spectacular with pink and purple colours which were the result of changes to the light of the setting Sun by particles in the upper atmosphere pushed upwards by the violence of the volcanic eruption. What Backhouse saw on the night of the 8th June, however, was rather different. These clouds were a pearly white, tending towards blue in colour, not the garish colours produced by the volcanic sunsets. It is likely to have been the colourful sunsets which allowed the discovery of these still unusual clouds as a number of historians of astronomy have failed to find any realistic reference to them before 1885.

More reports of sightings of these clouds were made and, as they were seen during the late evening and night, were given the name noctilucent clouds (NLC) or night luminous clouds. Reports and frequency of sightings gradually increased into the 20th century by which time they became a serious curiosity and were creating some questions in the scientific world. It was generally agreed that rising warm air cools and moisture carried by that warm air forms water droplets as the air ascends. These form clouds which could extend upwards to around 15km. Beyond this, very little water could be carried, and certainly not sufficient to form these clouds which had been measured to be at the remarkable height of around 83km. The clouds are formed of ice crystals and are illuminated by the Sun which is between 6 and 16 degrees below the observer’s horizon. James Paton, the then Director of the British Astronomical Association’s Aurora Section made an extensive study of NLC from his home in Abernethy until his death in 1974. Dr Mike Gadsden of Aberdeen University continued to make a detailed study of NLC from the Cromwell Tower of Aberdeen University until his death in 2003. I remember well Mike saying to me ‘These clouds shouldn’t exist. There should not be enough water at that height to allow visible ice clouds’. He also was the first person I heard who suggested that NLC may be a barometer of global atmospheric change (he said this before the phrase ‘global warming’ became popular).

[Continued ……. ]

Ken continues to explain how noctilucent clouds form, describes their role in space science, notably via the findings of the AIM (Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere) satellite and points to the importance of the sun’s cyclic activity (sunspots) on their recorded occurrence. His article can be read in full at the DundeeAstro page on this web site Clouds on the summer horizon. With thanks.

On the edge

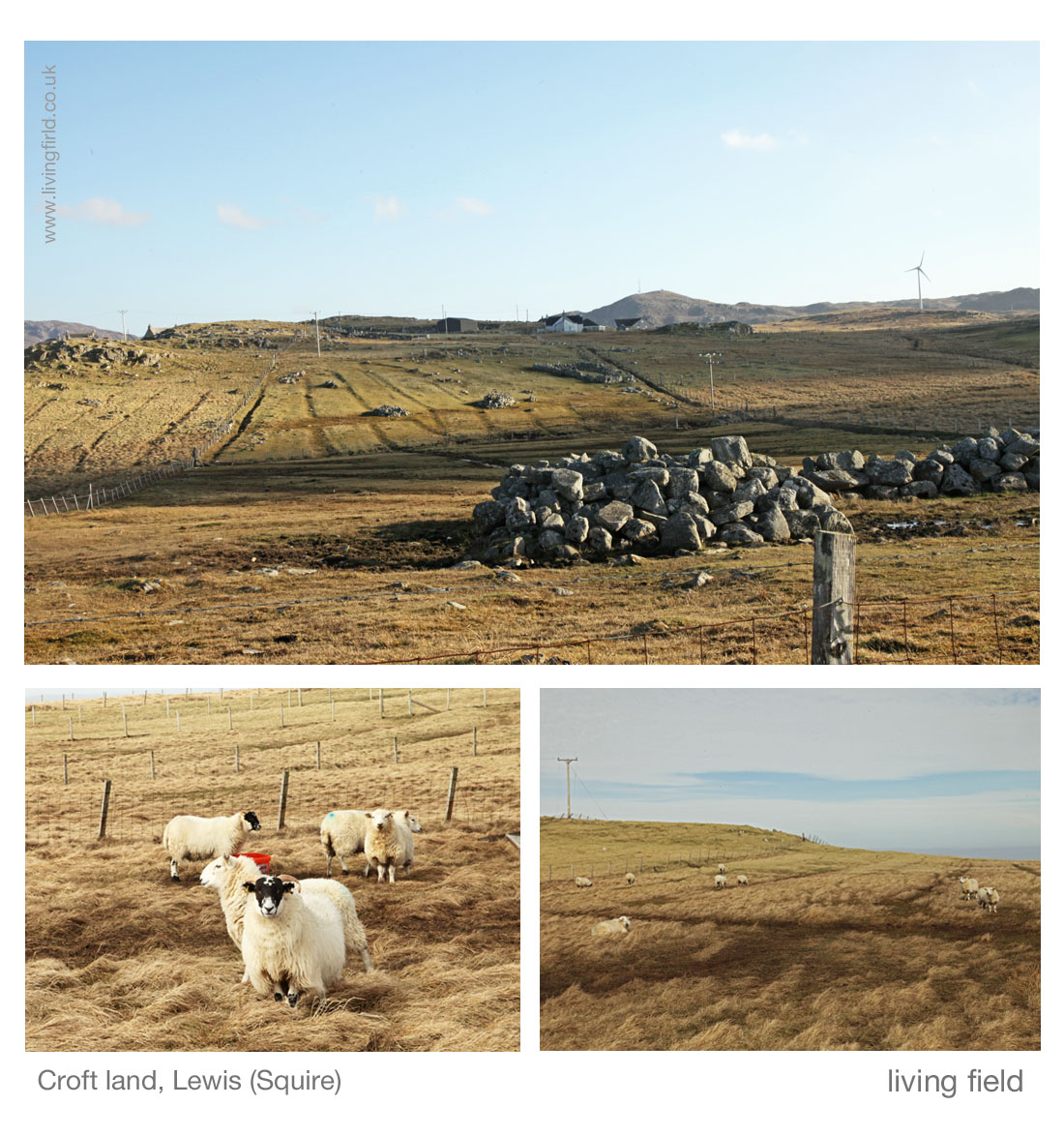

Remote, extensive rig system (lazy beds), north Lewis; historical records of crops from 1690s; bere and barley; subsistence farming on the atlantic edge.

One of the remotest field systems in Europe lies near Eoropaidh (Eoropie) on the north-west coast of the Island of Lewis, facing the Atlantic at 58 N. Continue round that parallel and you’ll cross Quebec in Canada, the Gulf of Alaska and Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula.

The Butt of Lewis lighthouse [1] lies at the northern tip of the Island. As you walk south west from there, the soil and grassy vegetation appear to be slipping towards the cliffs and into the sea.

A little farther south, and the cliffs descend to a rocky shore where the rigs or lazy beds were cultivated close to the tide. It’s a stunning position – go west and there’s no more land until north America. And what Atlantic storms there must be. Yet corn and other crops were grown here.

As testament, the rigs remain as long, grass-covered mounds 5 to 6 m between the furrows, some at more or less right angles to the coastline, others parallel to it. Earth was dug and piled from both sides into the centre and seaweed carried from the beaches and heaped on as fertiliser. Excess water ran down the furrows.

Extensive field systems

Extensive field systems

The rigs in the images are one of several field systems around Eoropaidh and Butt of Lewis. The Canmore web site [2] describes the field system in the photographs here, which lies south west of the lighthouse and facing west, and several others (round the ‘top’) to the south east of the lighthouse. All are abandoned.

They are considered to be post-mediaeval but period uncertain.

Aerial photographs are given for each location on the Canmore site [2] and other pages on that site tell more of the history of the area [3].

Lazy Hardly. Lazy beds in various parts of Scotland and Ireland were constructed to different designs. They are of various widths and heights. One explanation of the word is that they are made, not by digging up and completely turning sods of earth and grass, but rather cutting the sod on three sides, then flipping it over the uncut side to form a double layer – soil, vegetation, vegetation, soil. The method is shown in some recent videos [4].

But the most likely meaning is indicated by Fenton [4] as ‘from an obsolete sense of the English word (lazy), meaning uncultivated’, and refers to the fact that the raised bed is made on top of a strip of uncultivated ground.

Maintaining fertile rigs of the extent seen today around Eoropaidh was a major undertaking, needing the work of (according to Martin below) probably hundreds of people each year.

The method by which this land was managed is known as runrig, ‘a system of joint landholding by which each tenant had several detached rigs allocated in rotation by lot each year, so that each would have a share in turn of the more fertile land’ [5].

Fenton and Veitch (2011) give explanations and many references to the runrig system in different parts of Scotland.

Historical records

Several accounts of the area were made from the 1690s onwards, but they make no mention of the field systems and give little information on the crops and methods of husbandry.

Why this omission? The extensive rigs must have been there during one or more of these accounts, The landforms look impressive to us today, the result of decades, centuries, of hard work, and continued upkeep.

Martin Martin’s visit in the 1690s

Martin Martin, from Skye, visited Lewis in the 1690s and reported his findings in the Description of the Western Isles of Scotland, published 1703 [7]. On soil cultivation, he reported that the people turned the ground with spades; and with wooden harrows for breaking and smoothing the earth, drawn by a man ‘having a strong rope of horse hair across his breast’.

He writes ‘the island was reputed very fruitful in corn, until the late years of scarcity and bad seasons. The corn sown here is barley, oats and rye; and they have also flax and hemp.’ [8] He continues to relate that the main fertiliser is sea-ware but that soot is also used, reportedly causing jaundice in those who eat bread from corn grown on land so treated.

However, there is no mention in his chapter on Lewis of rigs, lazybeds or any means of land-sharing.

Potato is often associated with rig systems but it was not grown in Scotland until several decades after Martin Martin wrote his journal, so it would not have been on the Island when he visited.

A note of caution is due – Martin is not always credible. What a pity when reliable records from that time are so needed! At various places, he related what we would today consider fabulous or supernatural occurrences, without question, as if they happened.

He was knowledgeable about many things, so was he tempting readers with fake news, or did he not check his sources?

Old Statistical Account, 1797

The Rev Donald Macdonald wrote ‘not a single tree, or even any brushwood, to be seen in the whole parish’. The crops were black oats, bear and potatoes, sown April and May, reaped in September and October. (Ed: black oat is Avena strigosa and bere a landrace of barley, Hordeum vulgare).

He confirms the use of soot as fertiliser as reported by Martin a century earlier. He writes that the roof of each house is thatched with stubble and heather ropes (stubble presumably being cereal stems) which become covered in soot due to the burning of peat within. He writes that in the latter end of May when the barley blade (first leaf) appears, the people take the soot and stubble and strew it over the crops as fertiliser.

Many domestic animals were reported – horses, sheep and black cattle, all small in stature. The region was very isolated, things had to be carried to and from Stornoway.

Potato came to the area between Martin’s visit and this account, but there is no mention of rigs or lazybeds. Just that many crude ploughs are found in the parish, consisting of a small piece of crooked wood, guided by a side handle held by a man walking alongside, and pulled by four small horses.

New Statistical Account, 1836

The Rev William Macrae notes also the absence of wood or tree, but that roots and trunk of fir, oak and hazel (with nuts) are ‘imbedded in a great depth of moss, such that wooded land must ‘at some remote period, have undergone some sweeping and desolating revolution’.

He mentions that people eat oat and barley meal, potatoes and milk, but laments the state of farming: that people have not attempted draining or trenching because they were just too hard up, while short tenancies of 6-12 years did not making it worthwhile. It was a subsistence economy with no exports and in no season was produce more than ‘barely sufficient, and sometimes not adequate, to supply the necessities of the tenantry’.

There is no mention of field systems or rigs, and the comment on the absence of drainage is not consistent with what we see today, but he may have been generalising to the whole of Barvas parish rather than these rig systems.

The Rev Macrae commented on many other aspects of life. His account is entertaining, but you feel his mind sometimes strays: he is patient to note among the statistics of population, produce, and adherence to the faith, that ‘The women are modest, comely and many of them good-looking.’

Modern field strips

Visitors today will see the agricultural land in crofting townships on Lewis divided into long thin strips, usually separated by fences. The OS 1:25,000 maps show these bundles of linear features covering much land near the coast.

One of the stated characteristics of linear farming of the type shown above is that, provided the strips run perpendicular to the main gradient in slope or soil, no one strip gets the best land and no one gets the worst.

This sharing of good and bad appears to be one of the reasons why crops, especially in the tropics, are sometimes mixed in a field, not in clumps but in long straight lines [11].

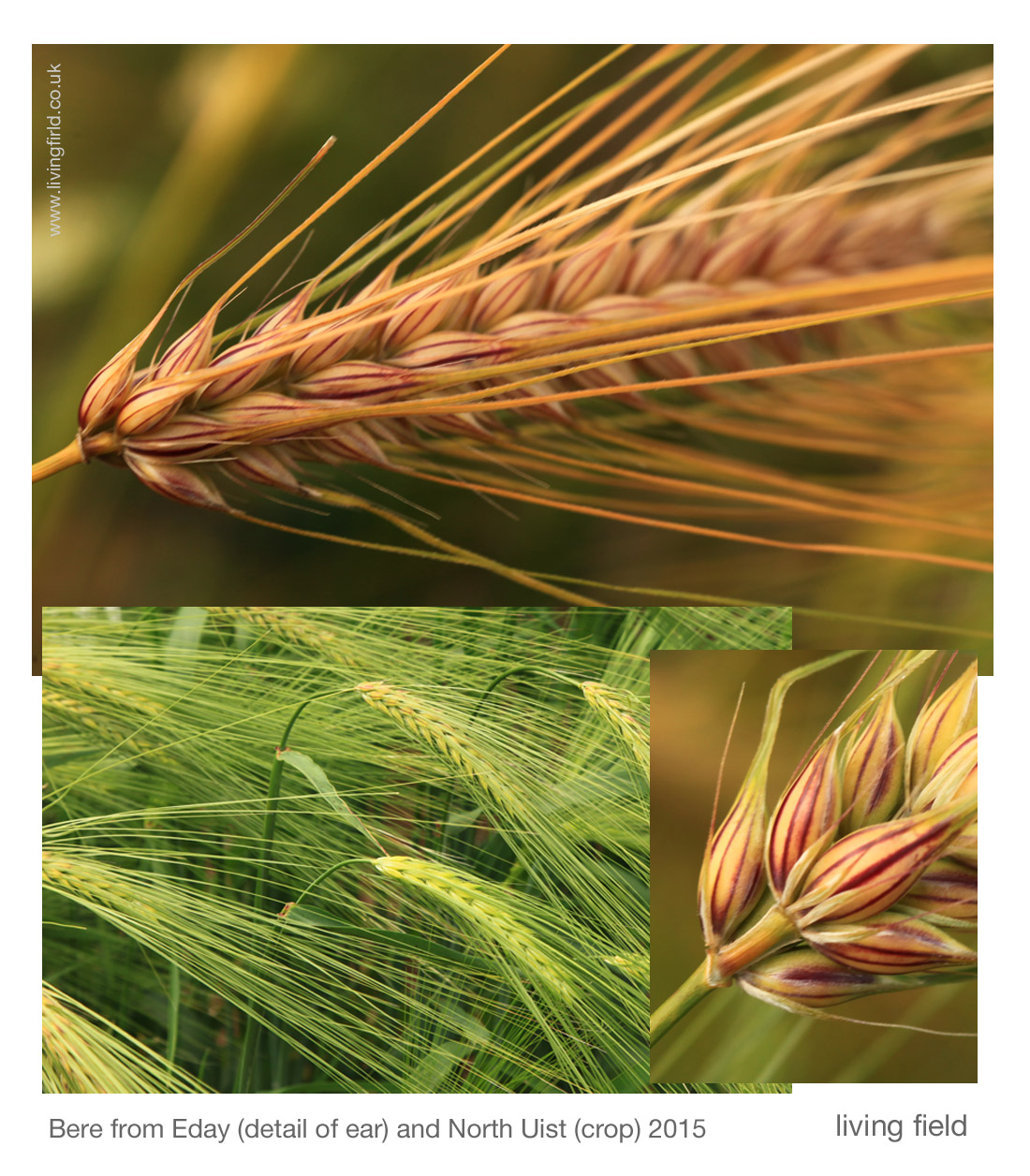

A note on bere and barley

The Living Field has a biding interest in when bere and barley were noted as being different things, e.g. that bere was a primitive landrace of barley. The story unfolds on this site at Bere line – rhymes with hairline.

There is nothing definitive in any of these historical accounts as to whether bere and barley were considered different. In the Old Statistical Account of Barvas parish [9], as noted above, both names are used for the barley crop but neither is defined.

In 2015, the Living Field team grew a range of old barley varieties in the garden, including some bere landraces originating from various parts of the north.

We had none from Lewis, but shown above are bere from North Uist in the Outer Hebrides and from Eday in Orkney. Barley grown in the lazy beds around Eoropie would have looked like this.

An achievement

The land was farmed in this way for centuries, in isolation from much of the rest of the world. Given the location, the rig systems in north Lewis and elsewhere should be seen as a major achievement rather than something to be dismissed as backward (as some travellers did).

Crop production was limited by plant nutrients – nitrogen, phosphate, potash and the many minor elements. Legumes that provided much needed nitrogen by fixation from the air were not mentioned in the historical accounts, and were unlikely to have been planted as crops here as they were during the Improvements era after 1700 in the lowlands.

Apart from seaweed and soot, and probably animal dung, there was no other source of nutrients. To have survived for so long on so little was the achievement.

Author and contact for this article: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk. Thanks to gk-images for allowing us to use some of their photographs.

[Began late March, edited in April and May 2017]

Sources

[1] Northern Lighthouse Board: Butt of Lewis Lighthouse.

[2] Field systems of lazy beds around Eoropie and the Butt of Lewis on the Canmore web site: the one shown in the photographs here is west of Eoropie, Canmore ID 129505. Others include ID 270561, ID 270560 and Dun Eistean ID 4417.

[3] More on the history of the area at the Canmore pages for Eoropie, Teampull Mholuaidh (St Moluag’s).

[3] More on the history of the area at the Canmore pages for Eoropie, Teampull Mholuaidh (St Moluag’s).

[4] Lazy beds: Guthan nan Eilean short video on making lazy beds in Uist (in Gaelic and English versions). A article from Ireland: Lazy beds in the Cooley Mountains. From the Louth Field Names project. The origin of the word lazy, from ‘uncultivated’, is explained by Fenton A, Ch 27, p 673 in Fenton & Veitch 2011 [6].

[5] Definition of runrig in the Concise Scots Dictionary. Ed. Mairi Robinson. 1985. Aberdeen University Press. Also: The runrig system of land tenure, fromThe Angus Macleod Archive via Hebridean Connections.

[6] Fenton A & Veitch K (eds). Farming and the Land. 2011. Publ: John Donald & European Ethnological research Centre. This multi-authored book has many references to runrig and lazybeds, including photograph of lazybeds at Eoropie (p 125); and a note that the runrig system in north Lewis may have been managed by small groups of people, rather than individuals.

[7] Martin Martin, 1703. A description of the Western Islands of Scotland. Printed in London. Available online: search Google Books for the author and title; also the Undiscovered Scotland web site offers the book online (with adverts). Undiscovered Scotland web pages: biography of Martin Martin, died 1719.

[8] Martin is probably referring to the Ill Years, the 1690s when a run of very bad weather caused repeated crop failure and consequently hardship and famine through the north of Britain.

[9] Old Statistical Account of Scotland, 1791-99: Vol XIX dated 1797 for the Parish of Barvas. Online at Old Statistical Account.

[10] New Statistical Account of Scotland, 1834-45: Vol XII for the Parish of Barvas. Online at New Statistical Account and also at Google Books.

[11] As argued in the editor’s account of Mixed cropping in Burma (Myanmar).

And if you are anywhere near latitude 58 N, make a point of visiting the famous –

Information at eoropiedunespark.co.uk

The Beauty of Roots

Exhibition, Dalhousie Building, University of Dundee, 17-30 March 2017. More images here.