The blackthorn Prunus spinosa is the first of the wild members of the genus Prunus, the cherries, to flower in the year. Its fruit – the black sloe – is not what we might expect of a cherry, being sour and unfit to eat, yet is used as a flavouring.

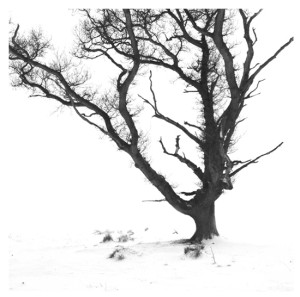

Generally the bush reaches full flower in mid-April while the leaves are still in bud, or just expanding, and where the plants are let to form thickets, they appear from a distance as if a heavy frost had covered the tangle of black branches.

The spectacle of a blackthorn thicket in flower has become uncommon in the croplands – relegated to higher ground on the fringes of rough grazed pasture or in lowland hedges that have been serially uncut. Massed thorn is sometimes seen as plantings around roundabouts and slip roads but seldom impresses.

It is a fine plant of the hedgerow but rarely flowers on branches that are trimmed short.

The flowers are simple and primitive, typical of the Rose family – five green sepals, which previously encased the flower bud, but now showing through the base of the five white petals, and many pollen-bearing (male) anthers ringing a central (female) style and stigma.

The flowers are held close to the woody stems, on stalks about 1 cm long, unlike the gean Prunus avium where the flowers hang in clumps on longer stalks and the bird cherry Prunus padus where they are held away from the stems on short floral branches.

The blue-black fruit, like a small dark plum, is used in drinks, gin and sloe wine, and has a long history as a medicinal and dye. It turns dark blue from green in autumn, and if not removed, remains black and slowly withering throughout the winter when the leaves are gone.

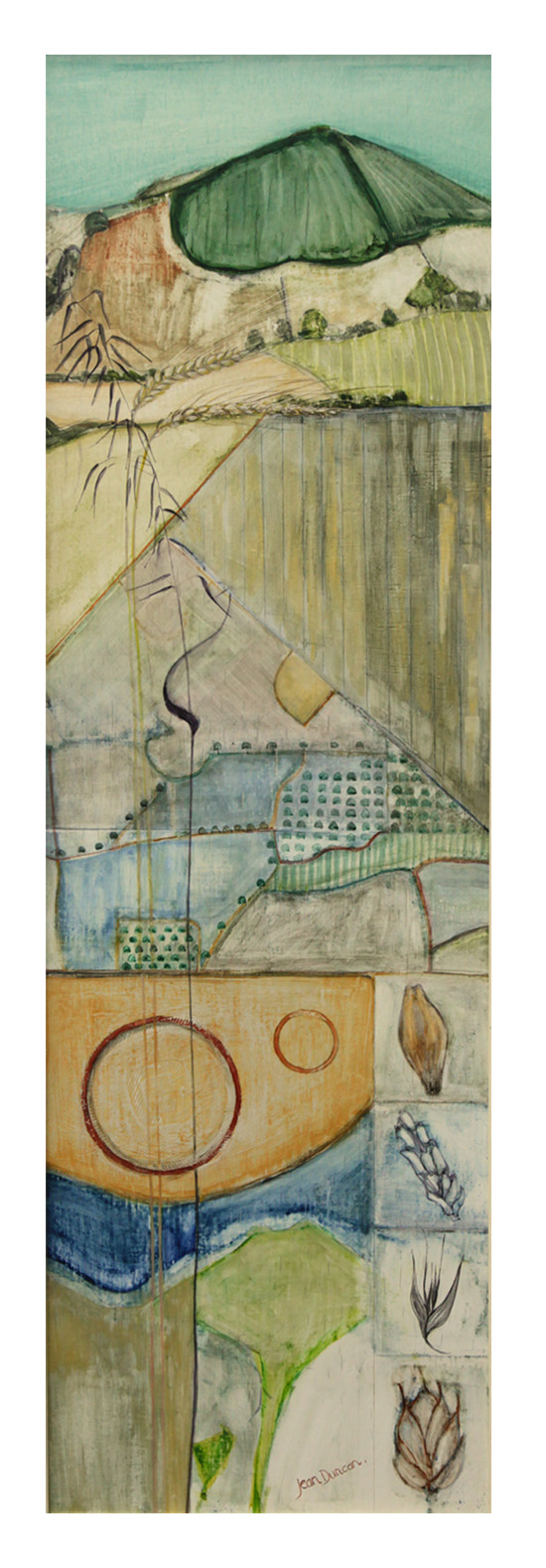

Occasionally the blackthorn grows into a small tree, as the one by a lane in the images below.