The very dry spring of 2017 not only set back crops but prepared moor and rough grazing for fire. These habitats are used to fire. They have evolved with it as a recurrent destroyer, at least since the last ice retreated and people returned in numbers to begin clearing and cultivation.

The problem for those today concerned about natural heritage is that fire does not discriminate, and while the burning of grass and whin (or gorse) Ulex europaeus will not affect their survival in most localities, it can devastate rare and declining, or even newly expanding, populations of other plants growing along with them.

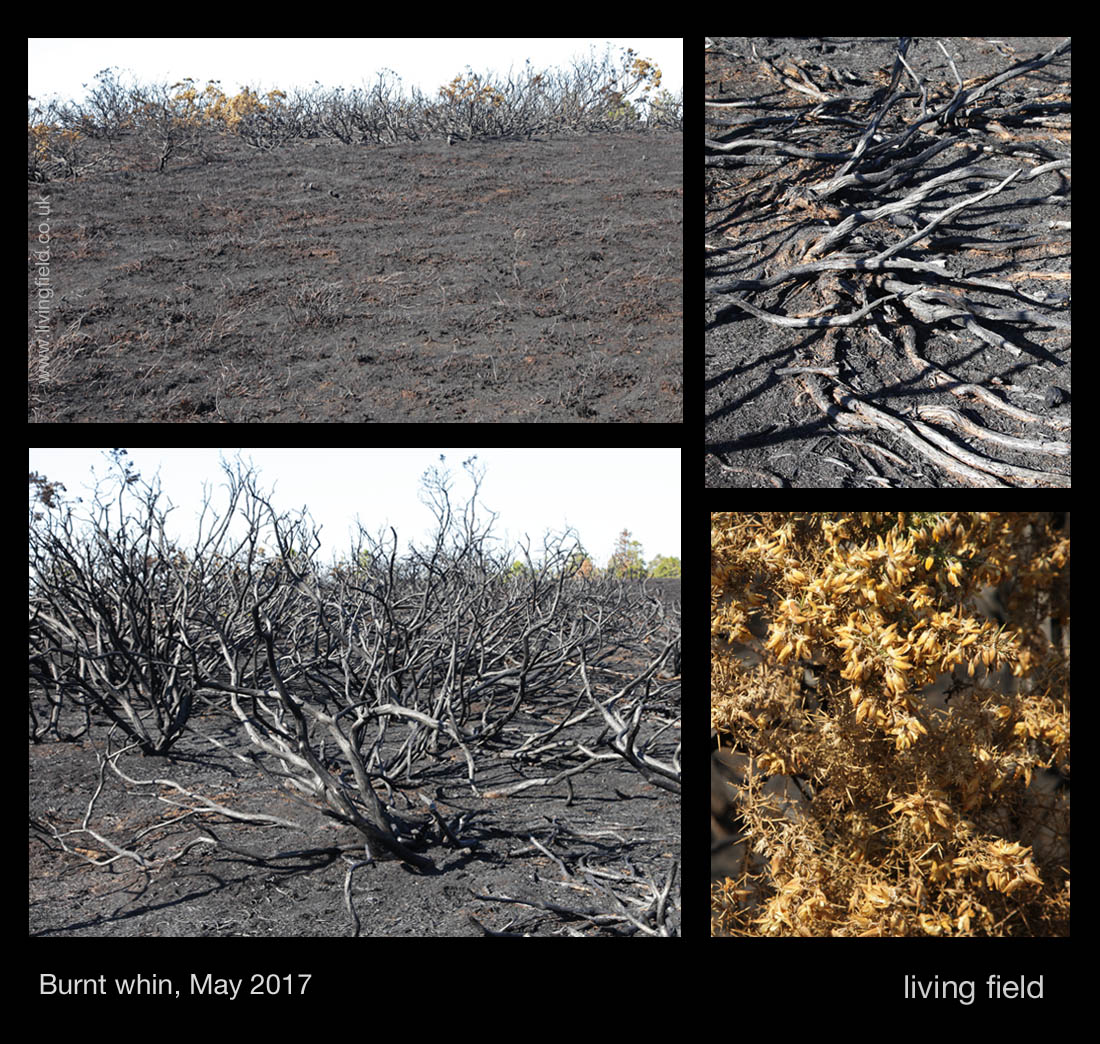

This was the case in pockets of whin-dominated land that were fired during the dry spring. Fire left the whin’s stems and branches like blackened bones. They appear intact, but they disintegrate to powder if you try to pick them up.

The intensity of the fire was so great in places that everything had been burned, but at the edges not all was lost. Flowering branches had been singed in the heat, no longer bright yellow, but perhaps not dead; and some small broadleaf trees such as rowan Sorbus aucuparia had one side singed and the other not.

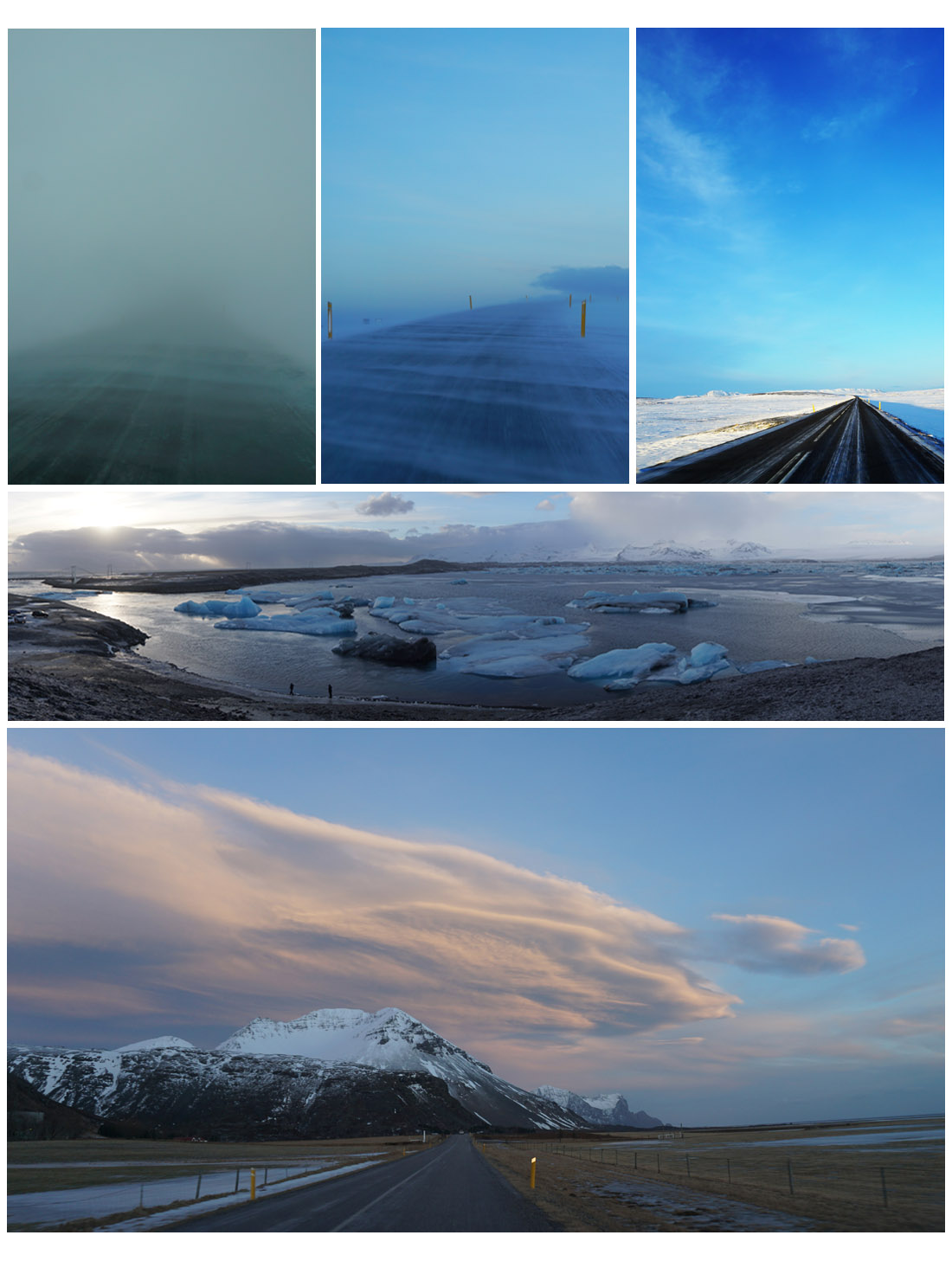

So what made an ‘edge’ that stopped the fire. In one area, it was a narrow road that the fire did not cross. In another it was wetter ground in a hollow that stopped the advance. (It takes a lot to completely dry out a bog in these parts.)

The images above (top) show a wet hollow or depression, which stopped the fire from consuming the willows in the middle ground but not the rough grass before nor the trees beyond.

The fire also failed to take some small areas. One (lower left above) appears to be nothing other than a small pile of droppings (deer?) which presumably was wet enough to prevent the surrounding grass for being blackened.

Threatened juniper

This small fire, covering just a couple of acres (not quite a hectare) would have destroyed any birds’ nests in its way, but it also destroyed juniper and young pine.

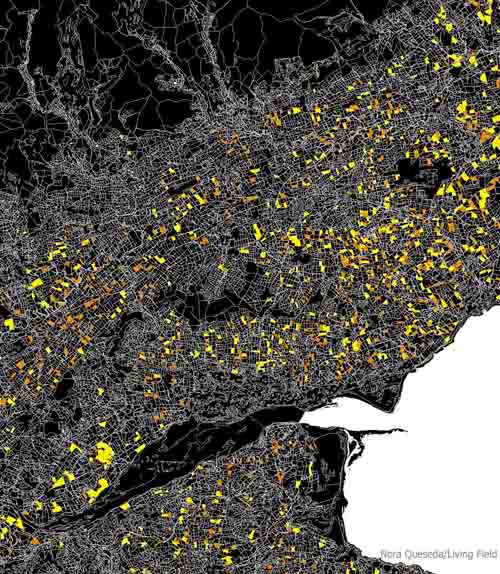

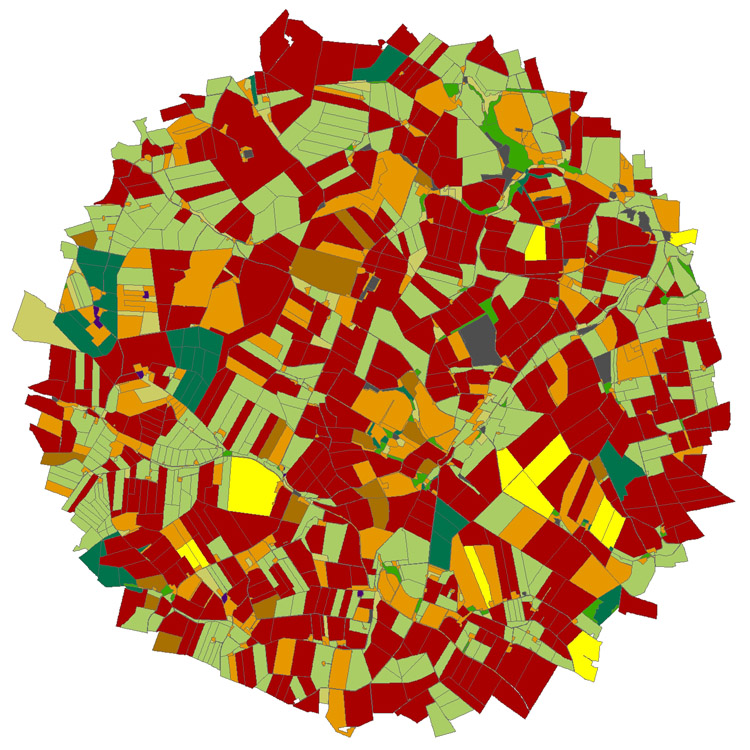

Juniper Juniperus communis is particularly vulnerable in many areas of Scotland because it is declining due to a range of factors including over-grazing and disease [1, 2]. The location shown in the photographs, within 10 miles of Inverness, falls within Zone 1, that of least concern for juniper conservation.

Yet here, even in Zone 1, within an extent of 5 x 5 km (25 square kilometres) juniper exists mainly as isolated mature bushes and some regenerating young plants, not as a complete stand.

It is heartening to see several young plants in this area [3], but not to see that in this one small fire, some young juniper were scorched to death.

There was evidence that the fire was more intense under and around some juniper (top left above), perhaps because the dead plant matter accumulating under the bushes was more flammable than the surrounding grass? Perhaps there were other reasons.

Also young Scots pine Pinus sylvestris were badly affected. The one top right above was 100 metres from the nearest tall mature native pine tree; and though it looks small, it could well be several decades old, checked in growth by the poor conditions. It’s a pioneer spreading from a native remnant, but not likely to survive this fire.

This was a very small bush fire by local standards, and insignificant compared to the fires raging over thousands of square kilometres in some parts of the world, but even so it caused a lot of damage to populations of juniper and Scots pine that are struggling to maintain or expand their range.

It may add to the demise of juniper in this region. The fire was probably started illegally by someone.

Links

[1] Forestry Commission Scotland. Conservation zones for Juniper. The locality shown in the photographs above is in Zone 1 (self-sustaining juniper populations – conservation management beneficial in some places to promote natural regeneration). See also Species action notes which consider juniper along with black grouse, capercaillie, red squirrel, pearl-bordered fritillary and chequered skipper.

[2] Forestry Commission Scotland. Planting juniper in Scotland: reducing the risk from Phytophthera austrocedrae. Link to Online Guidance.

[3] Scotland’s Nature (Scottish Natural Heritage). Good news for Scotland’s juniper.

Contact/author/images: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk