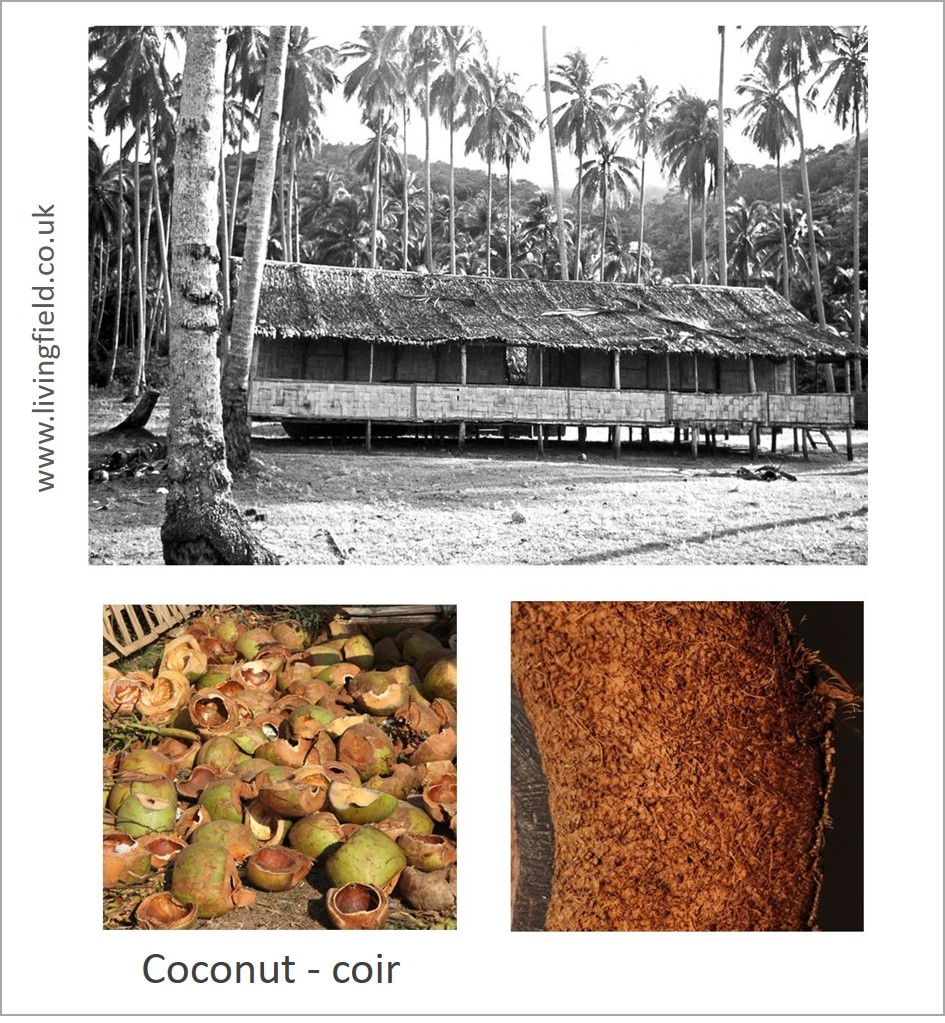

Examples of plant fibre and plant parts used in construction: coir from the husks of the coconut, simmens and sookens from oat straw. The Tang Shipwreck, found in the Java Sea, its hull planks sewn with coir. House roofs in Orkney protected and insulated with oat rope. Traditional uses of unprocessed plant material brought to life through museums in Singapore and Orkney.

Coconut fibre binds 9thC wooden hulled ship

The Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore [1] hosts a major exhibition on the Tang Shipwreck, found in 1998 in the Java sea [2]. The ship carried pottery before it sank, including many porcelain bowls made during the Tang Dynasty of China (618-907), far to the east of its resting place, and intended for export and sale to the middle east. They were decorated with homely designs, trees and flowers, but also fantastic sea creatures and other beasts (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Images of the Tang Shipwreck: a replica of the ship among examples of pottery; (upper right) a silver medallion; (lower right) bowl with fantastic sea monster; (lower left) a large pot in which many individual bowls were packed. From Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore (www.livingfield.co.uk).

It is not so much the surviving pottery and coins that caught the interest of the Living Field‘s roving reporters, but the way the ship’s hull was constructed. It was made of wooden planks, but they were not nailed or bound by iron. Rather they appear to have had holes bored in them through which coir fibre was passed to sew the planks together. The joints were bound with wadding and sealed with lime. The guidebook states ‘these techniques are typical of early ships made in the region of the (Arabian or Persian) Gulf and India’ [2].

The Tang ship was recreated using techniques as in the original and proved seaworthy during trials in 2010.

What of coir?

Coir comes from the husks of the coconut fruit [3]. The durability of coir can be seen in the many coconuts that are washed up on beaches throughout the region. Strands of the fibrous content of the husk appear clearer when the coconut has long exposure to salt water, during which the natural packing material disintegrates, allowing the coarse fibre to fall free.

Fig. 2 Coconut grove and palm-thatched hut typical on shores of the South China Sea (taken 1980s), discarded coconuts after food extracted (lower left), and part of a coconut in cross section showing the band of fibre about 5 cm wide (coir) between the inner kernel and the outer skin (www.curvedflatlands.co.uk).

Coconut Cocos nucifera is one of the most useful plants [3]: as food, drink, oil, medicinal, fermented alcohol, utensil, animal feed, fuel, roofing material, and more. In Europe, its flesh or ‘meat’ is widely used in oriental cooking, but more common is the coir fibre used to make mats and matting . The fibre surrounds the ‘nut’, the whole protected by an outer skin. More recent uses include the fibrous ‘compost’ in which some protected fruit crops are grown.

Orkney Simmens and sookens – oat rope

At that time of the Tang shipwreck, the Picts in Scotland were carving stones and cross-slabs, reaching a high point in European Celtic art. Like the Tang potters, they also depicted fabulous monsters. Little is known of how they built their ships, but there is no equivalent of coir here, nothing quite so strong and durable that grows ready-made on trees, except perhaps the stems of heather and worked willow.

A material moderately strong and durable was however used to make rope, and that was straw from the oat crop. The distant origins of oat-rope are uncertain, but it was still in use until recently in Orkney where it was called simmens, used in roofing and securing hay ricks [4].

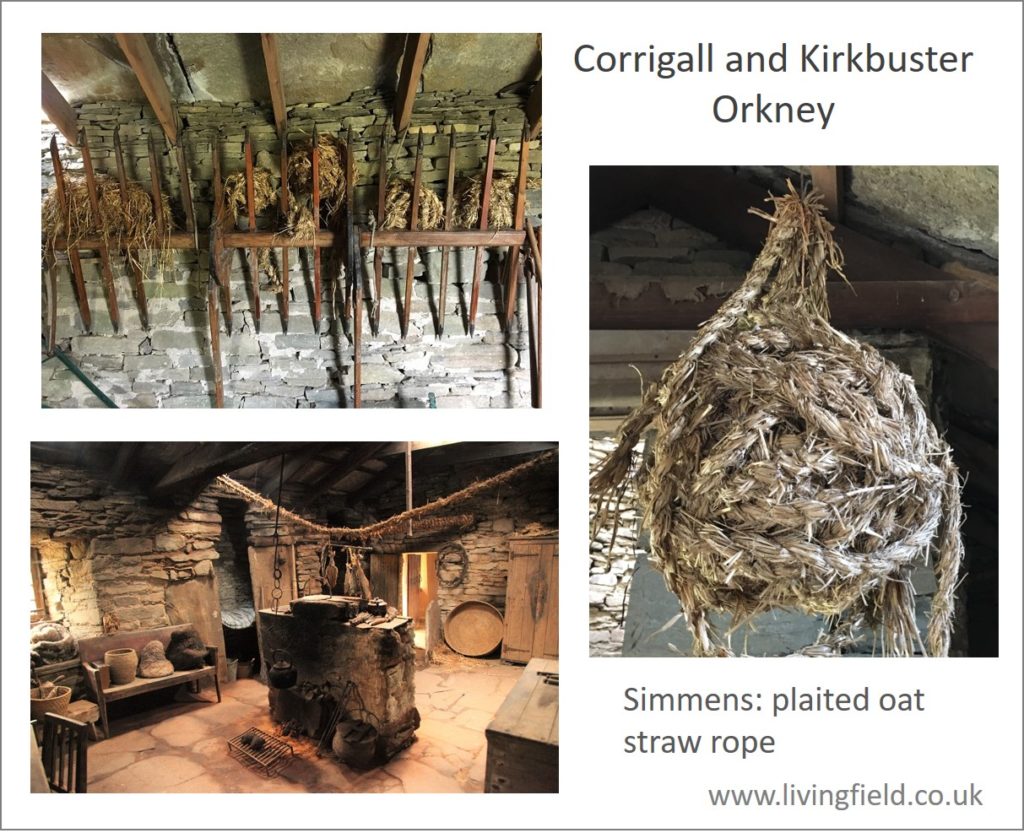

Fig. 3 Inside the Corrigall and Kirkbuster Museums on Orkney Mainland [5], showing plaited oat rope or simmens, balled for storage, and a rope hanging across the room over the fireplace (www.livingfield.co.uk).

Simmens is plaited from oat straw by hand, then typically stored as balls (Fig. 3). Its most celebrated usage was as a roofing material. It was looped from one of the eaves, over the top of the roof, down the other side, secured there and then looped back again, a procedure called needling.

The simmens rope was packed tightly to form a complete covering. In some places, straw was packed between successive layers of simmens and the roof completed with a final layer weighted down at the eaves by stones.

Where roof-stones were available, it was used as sarking, an inner layer, both as insulation and to secure thatch below the stone roof tiles. Vast quantities of oat straw – probably a few kilometers of it – were needed for a single house [4]. There must have been similarly vast quantities of long-stemmed oat grown to provide the straw.

The last few roofs that used it in Orkney were examined in the 1990s, but no attempt was made to conserve original simmens and it has all but disappeared. Could simmens be recreated today? One obstacle is ‘obtaining regular supplies of uncrushed, long-stemmed straw and the skill and amount of labour required to make and apply the simmens’ [4].

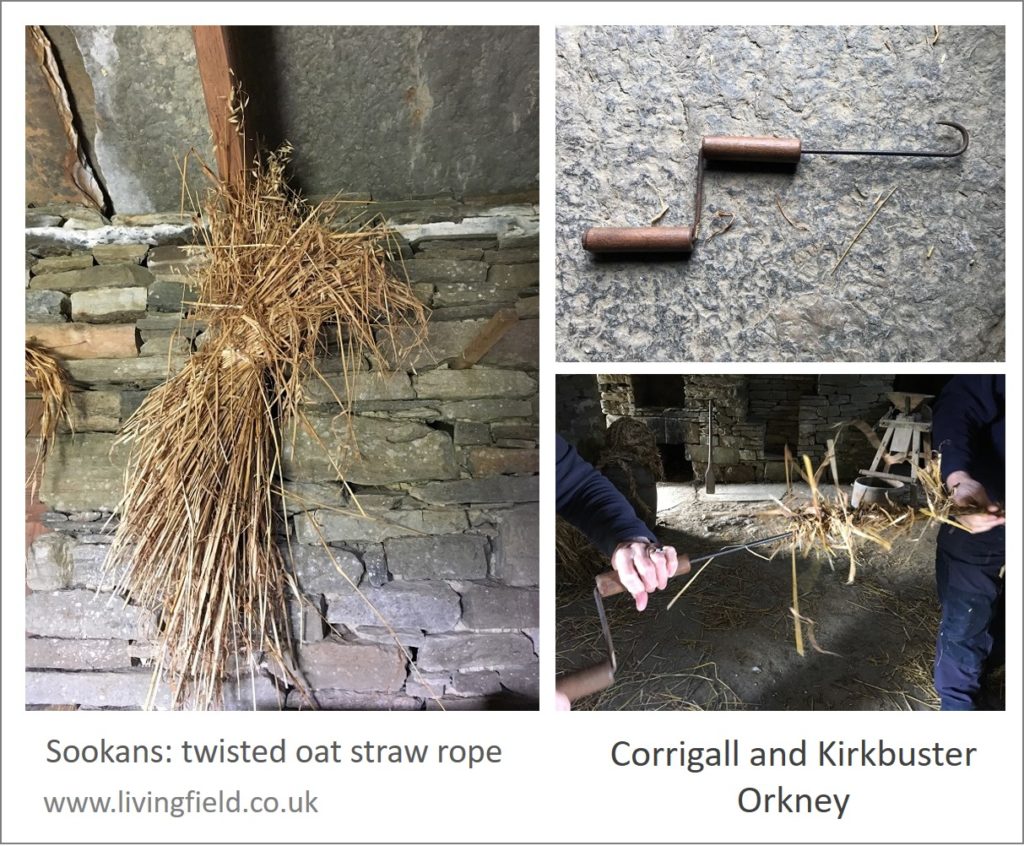

Simmens is on display at the Corrigall Farm Museum and the Kirkbuster Museum in Orkney [5]. Also demonstrated (on request) is a quick method of making temporary ‘rope’ or sookans from straw using a tool shown in Fig. 4. The tool is turned by one person, straw being fed through the hook, and the twisted straw pulled through by another.

Fig. 4 Oat plants, probably bristle oat Avena strigosa, a tool used for twisting the oat straw into sookans and twisting in progress, Corrigall and Kirkbuster Museums Orkney (www.livingfield.co.uk).

Fibre unprocessed

These two plants, coconut and oat, are two of a number from which structural fibres can be extracted and used without the need for any highly technical processing (though coir extraction takes much effort and skill). They and others like them, including sisal and heather, would likely have been used from well before settled farming.

The two museums visited in 2019 are both excellent in their own way, each displaying ancient crafts and allowing people to see, and in Orkney touch, the exhibits. We have to admire how the peoples from mediaeval times back through Iron, Bronze and Stone ages built their ships, strong enough to cross some of the most dangerous seas around the Northern Isles.

Sources, links

[1] Asian Civilisations Museum is by the river in Singapore. Web site: https://www.acm.org.sg

[2] The Tang Shipwreck exhibition is on permanent display at ACM – superb layout and information. The museum offers a free guide book from which the information given here was taken, but much more detail can be found in a book sold there with the title The Tang Shipwreck and on Wikipedia at the Belitung Shipwreck (another name for it) which covers construction and contents and also the controversy surrounding excavation.

[3] Coconut fibre or coir is a protective coating between the inner ‘shell’ that shields the ‘flesh’ and milk and the outer tough skin. The fibre has become a substitute for peat in some horticultural uses, but its transport to Europe from the tropics is hardly sustainable as is sometimes claimed. The Wikipedia entry is useful: Coir. The Living Field relies for information on Burkhill’s massive treatise on the uses of plants (A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsular, 1935, 1966) which describes the long process by which coir is extracted and made ready for use.

[4] Simmens (but also simmans and simmons in various modern sources) is made by plaiting oat straw. A photograph of simmens being used to thatch a roof is reproduced on the Living Field site at 5000/Fibres. The Scottish National Dictionary under Simmen gives examples of usage over the past few hundred years and indicates a Norse origin. Its use in roofing is described in the booklet:

Newman, P, Newman A. 1991. Simmens and strae: thatched roofs in Orkney. Extracted from ‘Vernacular building’ published by the Scottish Vernacular Buildings Group. Herald Printshop, Kirkwall.

[5] Orkney museums provide authoritative and very helpful and practical guidance to natural products and past farming. The main site is in Kirkwall – The Orkney Museum. The Corrigall Farm Museum at Harray and the Kirkbuster Museum Birsay are both in restored farm buildings.

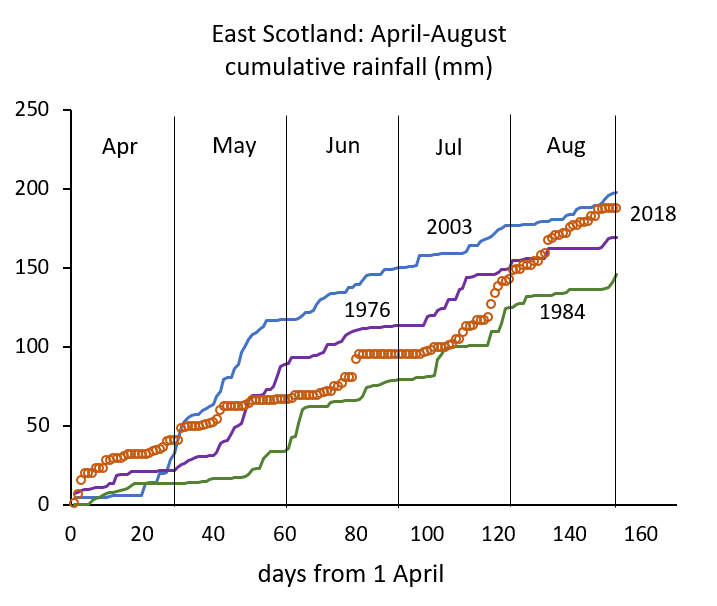

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@outlook .com.