The gool or corn marigold, for centuries an injurious weed. Its control by monastic order. Its decline in the 1900s and its rarity today except in wildflower seed mixtures. But will its recent reappearance in fields revive the ancient tradition of gool riding?

The gool, the Corn marigold Chrysanthemum segetum, was a pernicious weed. It ravaged the croplands in the middle ages [1], was tamed to a degree by the monastic improvements after 1200, and was finally brought in check late last century by mechanical cultivation and chemical weedkillers. Was it eradicated – not entirely? It’s still with us, seen emerging in stubble this autumn in a few east Perthshire fields.

Of all the main crop pests In Britain, weeds are now considered the most controllable and least damaging, but for most of history they were the scourge of agriculture.

The problem lay in the uncleanliness of saved seed. Corn crops, mainly barley, oats and wheat, were sown each year using seed saved from a previous harvest. If weed seeds were harvested with the corn, then the weeds were sown with the new crop. Seed would also reside for years in the soil ‘seedbank’, so that even if sown corn was clean of weed seeds, some from the seedbank would germinate and emerge when the soil was cultivated.

Good monastic practice

To avoid major weed problems, seed and soil had to be kept low in weed seed over a run of many years. Franklin [1] reports that gool was one of the most troublesome of the weeds that limited corn yields during the period of agricultural improvement initiated by the new monastic houses, such as Coupar, established in the late 1100s. The monks, and the lay brethren who did the farming, were aware of the need to keep seed and fields clean, and were able to achieve good agricultural yields and self-sufficiency.

Gool had such importance that it was named in leases from Coupar Abbey to agricultural tenants in the 1400s. The tenants were charged with certain tasks – to maintain trees and hedges, to include the soil-improving peas and beans along with corn in the rotation, to ‘labour for the gaining of the marsh’ (probably referring to the draining of the Carse of Gowrie) … and to keep the land free of corn marigold. Not everyone was as mindful as the monastics, but to encourage good practice tenants of Coupar Abbey were fined in the 1470s because they allowed gool on their land.

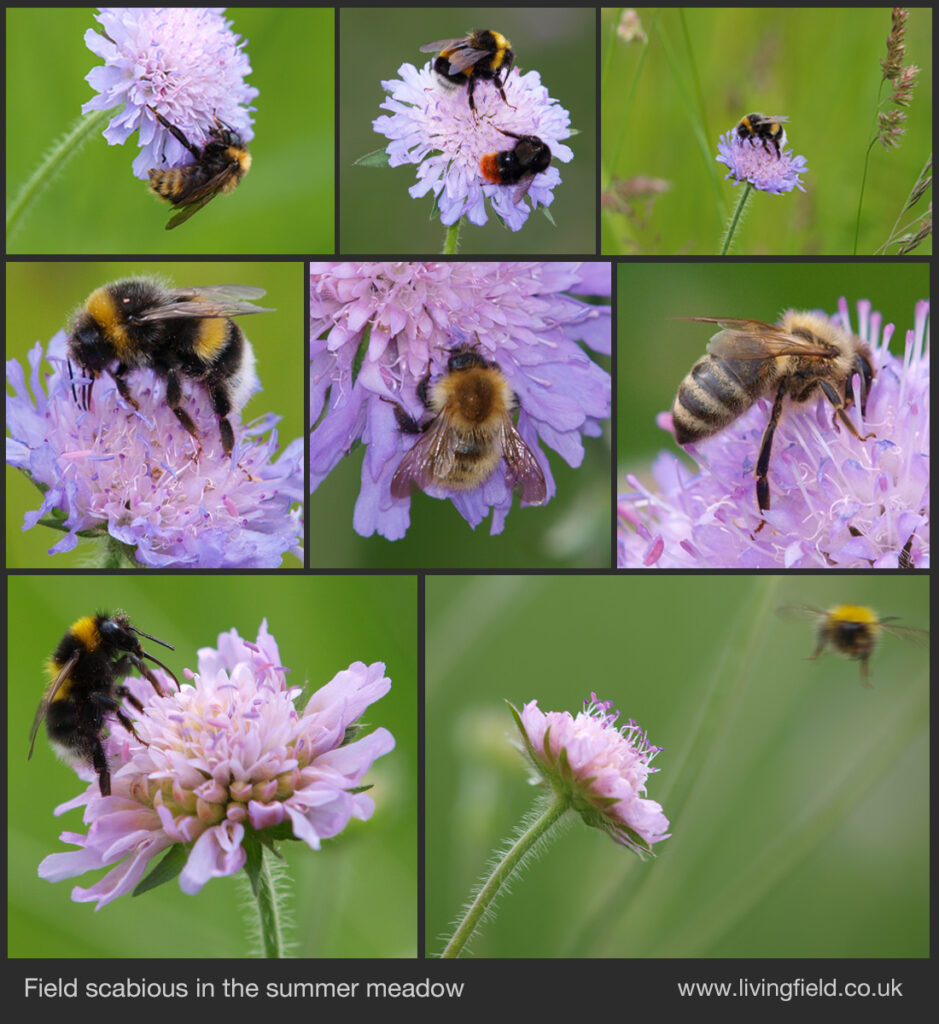

Today, the gool is not a problem. Rather its loss for most fields is seen as a negative. The marigold adds colour to the landscape and offers food for many invertebrates. Crop seed is sourced mainly from specialist seed merchants who ensure that ‘seed’ crops (those grown for seed rather than food or feed) are free of weeds. And even if it were to emerge in fields, modern control measure would remove it.

Gool riders approaching

Imagine being there in those mediaeval times and – weeds being weeds – they have this habit of just turning up whatever measures were taken to control them. Or maybe control lapsed and the gool took advantage and spread, wreaking havoc in the cereal crops.

And then in the early hours, distressed cries shatter the peace – “Gool riders approaching”. People scramble to pull on their clothes rush out to beat up any nearby gools and then head for the woods or whatever hiding place they can find to escape the landlord’s wrath.

Fanciful perhaps, but gool riders were a reality: “certain persons, styled gool-riders were appointed to ride through the fields, search for gool, and carry the law into execution when they discovered it” [1]. The riders were appointed (it seems) by major landowners: fines could be severe – a sheep for a gool.

Time out of mind

How widespread was the pursuit? Both Franklin and the Scots Dictionary [2] cite the one report in the Old Statistical Account [3] for Cargill, Perthshire. The Account was published in 1794 and refers to gool riding only as an old custom, so it is unclear when the riding ceased. The threat of the riders and the fines seemed to have worked because the Account reports that once tenants learnt to control the weed, the ‘gool-riders can hardly discover as many growing stocks of gool, the fine for which will afford them a dinner or a drink.’

There’s another mention of it, this one in Andrew Wight’s travels of 1778 [4]. In the barony of Stobhall, at Campsey (not far from Cargill), he tells of ‘a singular practice, which is called riding the guild‘, whereby a committee of tenants ‘on a certain day in August, examine every field, ….. and for each stalk of that weed found at this time among the corns, the committee fine the tenant in one penny or two pence’ and ‘by the observance of this salutary practice, the whole lands ….. are perfectly clean : whereas if we turn our view to the neighbouring lands, many of the fields are covered with more guild than corn.’

Wight enquired when the law was introduced and reported that ‘The people have no tradition relative to the time and manner of its beginning; only that, in time out of mind, such has been the practice’.

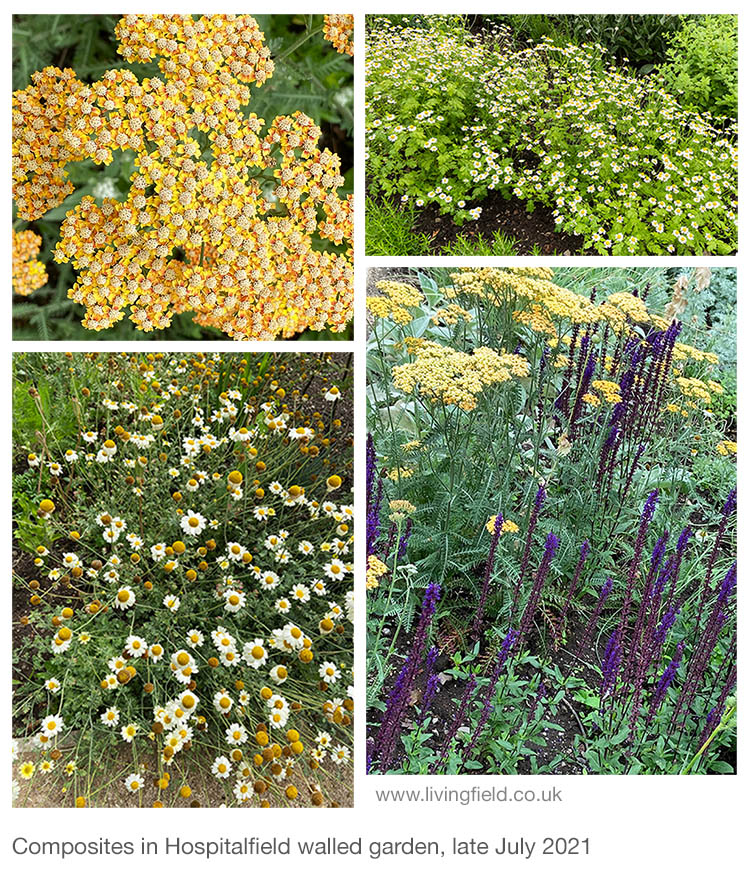

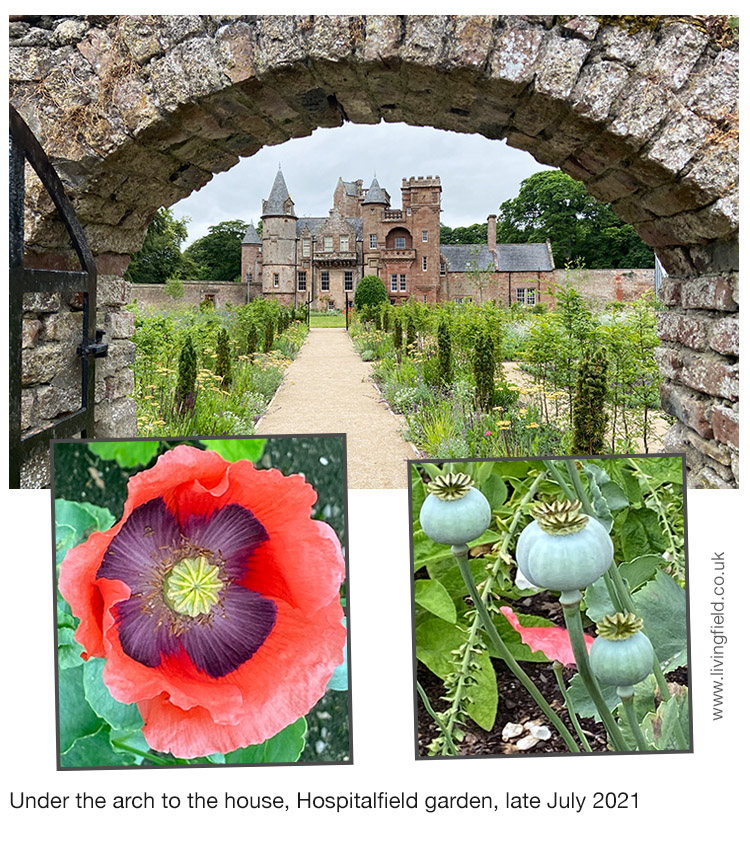

Today the corn marigold is common in sown annual wildflower displays, blending its yellow with the red of poppy and the blue of cornflower. Maybe some escape, the seed falling into people’s wellies and turn-ups, and eventually find their way into fields.

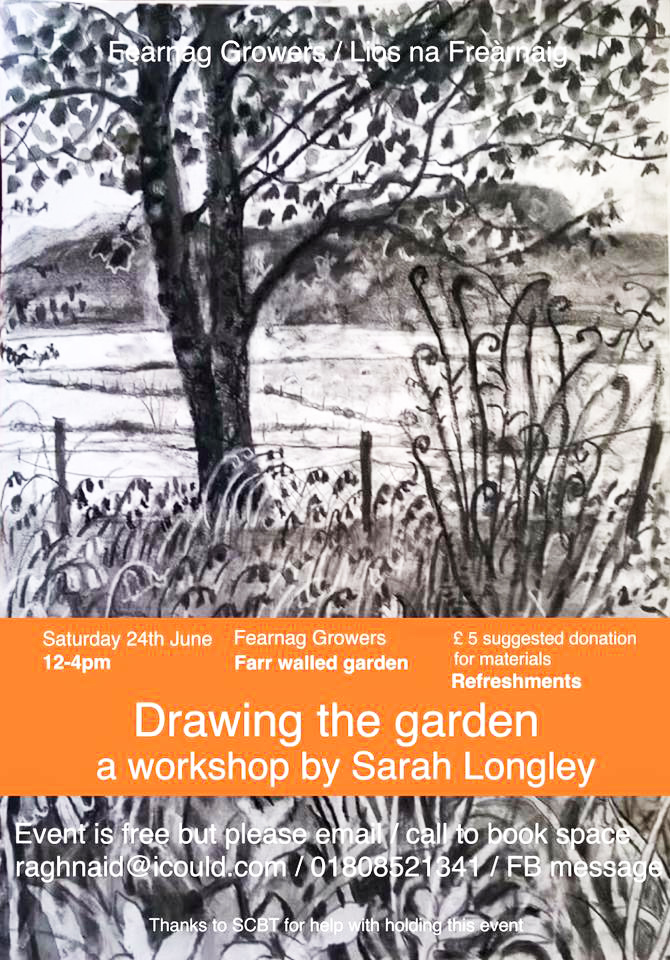

The gool shown in the cereal stubble at the top of this page grew mostly after harvest and flowered late, in October. It might have lain dormant in the seedbank, or came to the field in as a seed impurity or casual immigrant.

In the face of modern competitive crops and weed control, the gool is unlikely to wreak the havoc that it did. Its continued presence and reappearance serve to remind that food security was once threatened by weeds here, as it is now in many other parts of the world, and that there might be opportunity for this attractive plant to coexist with today’s agriculture.

Sources | links

[1] Franklin, T Bedford. 1952. A history of Scottish Farming. Thomas Nelson & Sons Edinburgh.

[2] Old Statistical Account, 1794. Cargill, County of Perth, Volume XIII by Rev Mr J P Bannerman.

[3] The Scottish National Dictionary (1700-) cites many variations including gool, gule, gweel and guild, https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/guil. One entry refers to a guil-sieve as a small mesh sieve in the threshing mill which cleans the corn after it has come through the riddle.

[4] Present State of Husbandry in Scotland 1978, Vol I, page 35. The author Andrew Wight is not credited. Available online, search for the title. More on Andrew Wight’s travels at Great quantities of aquavitae II.

Author/contact for this post: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk ot geoff.squire@outlook.com