By Kathryn Owen

I think it was the great sculptured stone of Nigg that did it…… How could someone have carved a stone of that size, with such intricacy, such imagination and such skill with just a hammer and chisel? And 1200 years ago?

So that was how I became hooked on Pictish sculptured stones. I visited Tarbat Ness in Easter Ross and the beautiful little museum in St Colman’s Church at Portmahomack [1] to find more examples and history retold as a story. Martin Carver of York University began fieldwork on the site in 1994 [2]. The team uncovered extensive monastery grounds near a stone church probably dating from the 8th Century, with evidence of metalworking and vellum making but also many carved stones, all in pieces.

The evidence of vellum making indicates that a scriptorium (place for creating manuscripts and illustrated gospels) was in existence at that time. There is discussion at the moment too, as to whether the ‘Book of Kells’ [3] could possibly have been created, in part perhaps, at the monastery of Portmahomack. If true ……..now there’s a legacy!

From there, I visited the other great Pictish sculptured stones of Tarbat Ness – the Hilton of Cadboll Stone and the Shandwick Stone [4]. There is a replica of the Hilton of Cadboll Stone, carved by Barry Grove [5] and now in its original position. The actual Stone is in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. The Shandwick Stone is covered by glass and is therefore protected from the elements, in place in the village of Shandwick. The Parish Church of Nigg houses the Nigg Stone, without glass, and it is the original – not a replica – and it is amazing!

Once I had seen these huge sculptured stones I began to find out more about both the Picts and their stones. Eastern Scotland is rich in its Pictish Stones, as is Morayshire, and there are so many to see, some in situ and some in museums. Some are well-protected but many are not – they are still in fields without even wooden structures to protect their artistry and their story. They are vulnerable to rain, snow, changing temperatures and the farmer’s plough.

The stone in the photograph below, called St Martin’s Stone, is still in a field at Balluderon, Angus, exposed to the elements, and the sculpted figures and beasts are very faintly seen. This monument, was created 1300 years ago but seems to be no longer respected as significant in 2022. The damaged rusty fence constructed around it may protect it from the plough or tractor, but not the weather. Should we not be doing more to protect these stones?

Iconography

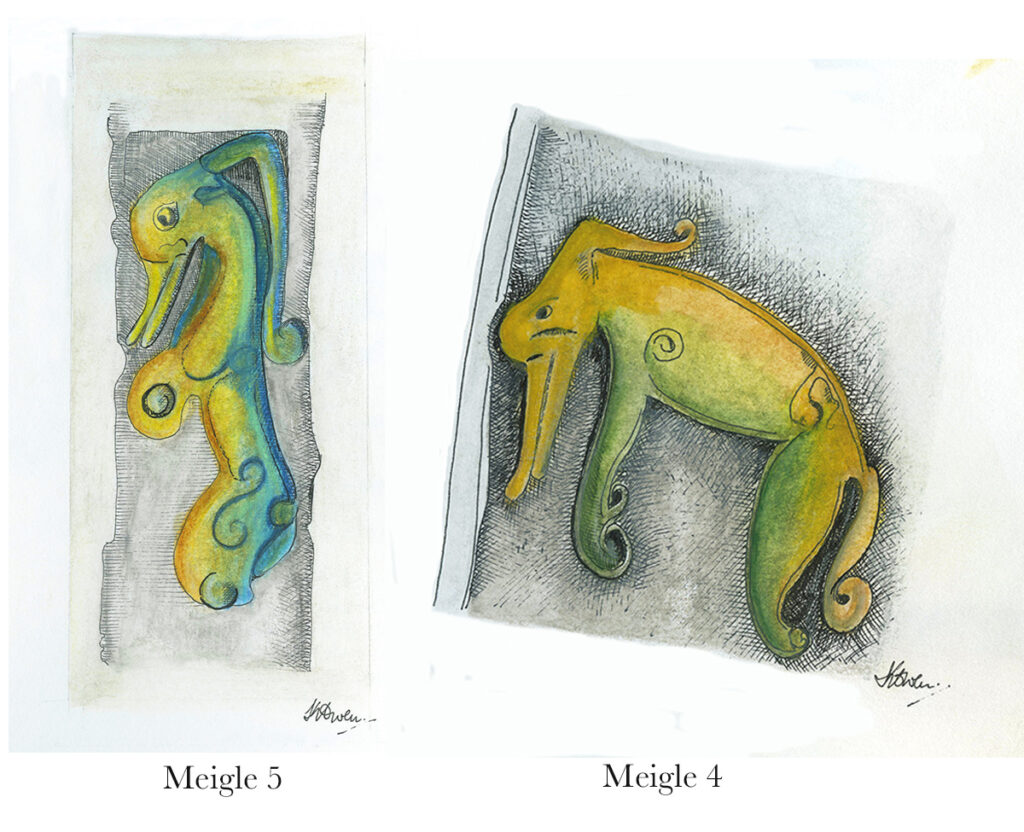

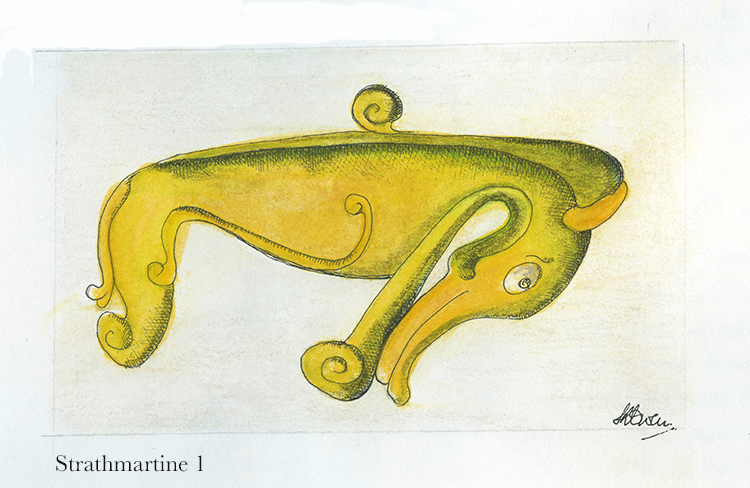

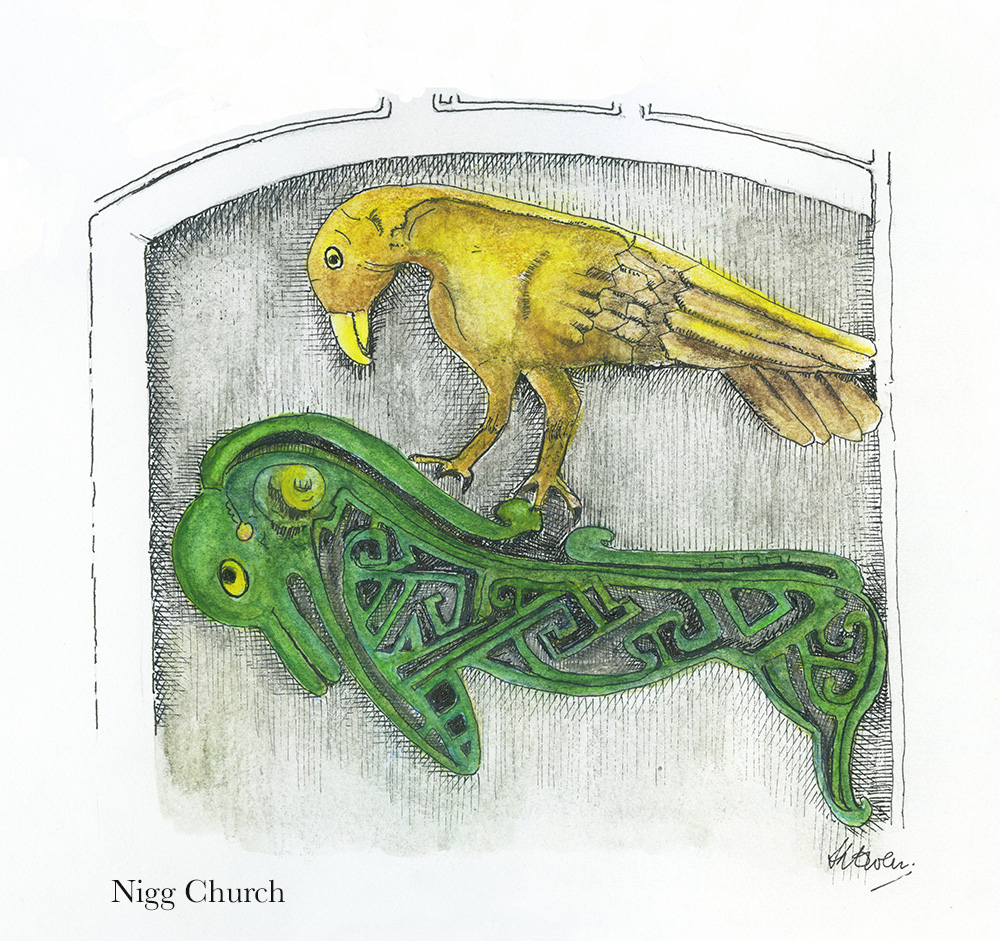

I began seeking out Pictish Stones, taking photographs of the stones and their sites and recording the iconography of the stones. The stones have a wide range of symbols and strange motifs, of key patterns, or interlaced knotwork, of figures – many on horses, some clerical, some warriors, some musicians, and then there are the beasts! There are entwined sea horses, strange dragon-like animals, birds like eagles or ravens, angry limb-eating monsters and also the ‘Pictish Beast’. This beast is strange – it has a snout like a dolphin, a crest or mane like a horse, four weird appendages which could not really be called legs or fins and then a tail! It has sometimes been called the ‘elephant beast’, maybe because of its large trunk-like head.

One of my projects was to find as many Pictish Beasts as I could, photograph and draw and paint them. There is evidence that the stones had been painted after they had been sculpted. The colours of the paint would have been the basic dyes available to the sculptors at the time (e.g. woad, madder etc.). I like to think of my pictish beasts as being somehow toned with the blues, greens and yellows that remind me of sea reflections. I suppose I do see the pictish beast as a water animal but this is just an intuitive feeling about it! I have drawn about 10 beasts so far and there are about 50 odd altogether – so I have a long way to go.

Here are some of the ones I have completed so far, with details of the stones, where they can be found and any interesting points about them.

Rodney’s Stone – Brodie Castle in Morayshire

Rodney’s stone is a 2 m high cross slab located on the approach to Brodie Castle, originally found in the grounds of the old church of Dyke and Moy nearby. There is also an inscription in ogham alphabet [6] on the stone and this contains the name ‘Ethernan’ who was a Pictish Saint.

Note that the Pictish beast has ornate interlacing on its body, not that usual.

Meigle, Perthshire

There is a great museum in Meigle in the former Parish School built in 1844 [7]. There is archeological evidence of an early church or monastery from 9th century. There are 27 Pictish stones and about a third of them are magnificent cross slabs and the stones are each numbered [4]. This Pictish beast (left below) is found on the side panel of Meigle 5 and looks fairly amused. The other – the grumpy one – is found on the reverse of the stone called Meigle 4.

Local Stones – McManus Museum, Dundee

There have been a number of Pictish Stones found around Dundee and in Angus. I visited the local McManus Museum and also the Meffan Institute in Forfar [8] and was delighted to see the large number of stones on display. Strathmartine is an area of Dundee to the north west of the city where stones have been found on farmland. A pictish beast is found on Strathmartine 1, 3 and 6 [4]. This one is Strathmartine 1 and was found in a field between Strathmartine Castle and Gallow Hill.

Aberlemno, Angus

This stone of a pictish beast with a horse shoe above it was found in Aberlemno in the 1960s, again in a field. Aberlemno has a collection of outstanding Pictish stones, simply standing at the side of the road and in the grounds of the parish church. Another stone has recently been found in a nearby field during an archeological dig by Aberdeen University. A visit to Aberlemno really is inspiring to see these stones in situ, along the roadside and in the graveyard of Aberlemno Kirk [9].

Rossie Priory, Perthshire

The Rossie Priory Stone in Perthshire is protected in a family mausoleum. It is another highly carved, ornate and artistic stone and this beast is part of it. The heads below the beast are of a two-headed dog.

The Nigg Stone, Easter Ross

The Nigg Stone was broken in the 1800s when it was being moved and later repaired with a steel frame and an insert. The missing part on the reverse side of the stone had a Pictish beast and bird sculpted upon it. We know this from a drawing by Charles Petley in 1811/12.

I attempted to recreate this image of the beast from faint sketches found on Canmore [4] and in the Tarbet Ness Discovery Centre at Portmahomack [1], but also added in the interlacing that was in the original. I have found, so far, only two pictish beasts that contain interlacing and these are Rodney’s Stone and Nigg Stone. My drawing (below) shows an eagle above the beast and there are other stones where an eagle is below a pictish beast. There seems to be a relationship between these two – the eagle and the beast – but what?

More to be found

There are more pictish stones being discovered by various enthusiasts and professional archeologists as we move through 2022 into 2023. Recent finds include those at Aberlemno in 2021 [9] and Kilmadock in September 2022 [10].

Pictish Hill Forts are being futher excavated such as those at Burghead in Moray [11] to reveal great fortifications and more Pictish artifacts.

I hope more pictish beasts will be revealed but I have a long way to go to photograph, draw and paint all of them. Maybe I will not finish the task, but it’s a fascinating project so far!

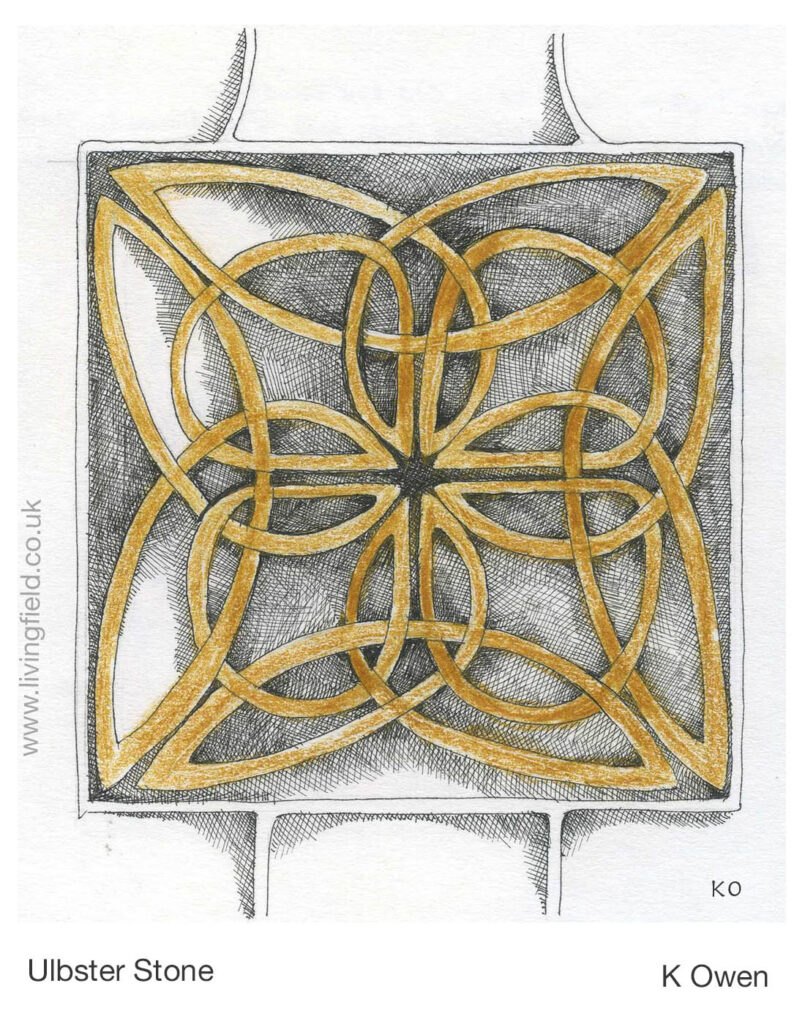

Finally, details of the various beasts, the beautiful interlacing and key patterns can be found in the book by George Bain [12]. Bain describes and draws detail from Hilton of Cadboll, Shandwick and Nigg Stones but also instructs and guides readers into the art of Celtic design and construction. This is a great book for anyone wanting to learn more about the art of celtic drawing.

Sources | links

[1] St Colman’s Church is now the site of the Tarbat Discovery Centre, Portmahomack, Easter Ross, which gives history of the site and wider area, and displays stones found locally.

[2] Portmahomack Monastery of the Picts, 2nd edition 2016, by Martin Carver. Edinburgh University Press.

[3] Book of Kells: see Trinity College Dublin at Shine a light on Irish history and the National trust for Scotland at The Book of Kells. The possibility that the Book could have been produced at an eastern Scottish monastery is considered by Victoria Whitworth (link to the Tarbat Discovery Centre).

[4] Photographs, drawings and information on Pictish Stones can be found by searching the Canmore web site (National Record of the Historic Environment) and in books, for example: Allan, J. Romilly and Anderson, J. 1903. The early Christian Monuments of Scotland, Vols 1 and 2. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Numbering of the stones, useful where several are found or exhibited at the same site, usually follows that set by Romilly Allan.

[5] Barry Grove, sculptor: see the Halfmoon.tripod web site at The modern Pictish Stones of Barry Grove (Ed: link broken when checked 2 Oct 2022; same 29 Nov 2022) and the ARCH web site for an article by Susan Kruse Carving Pictish Stones.

[6] Ogham – an early mediaeval alphabet from Ireland. See the web sites: OG(H)AM for a current research project; articles by David Stifter, Maynooth University, e.g. Language and epigraphic culture ‘OGAM’; and ogham.co for history, symbols and translations.

[7] Meigle Sculptured Stone Museum at Historic Environment Scotland.

[8] McManus Art Gallery and Museum, Dundee and the Meffan Institute, Forfar (link to Angus Alive)).

[9] Aberlemno – Historic Environment Scotland web at Aberlemno Sculptured Stones. More at the web pages of Aberlemno Kirk – the Stones. YouTube video Rare Pictish symbol stone found near site of ancient battle.

[10] Kilmadock – stone found by ROOK Rescuers of Old Kilmadock (link to their facebook page).

[11] Burghead excavation, Moray – University of Aberdeen web at Scotland’s largest Pictish Fort and the Burghead Visitor Centre.

[12] Celtic Art The Methods of Construction, by George Bain, Constable and company first impression 1951.

Editor: many thanks to Kathryn Owen for sharing her experiences and drawings of Pictish Beasts. Pictish art is a legacy of global significance, originating in our croplands but appreciated far beyond.

For more art and craft at the Living Field – Ancient and modern – techniques with wool in textile art by Ruth Black, Repurposing grass pea as an embroidered textile and hand made paper by Caroline Hyde-Brown, Owlbirds by Kit Martin, and pages on this site by Jean Duncan and Tina Scopa.