The store-house of Foulis; more from the Andrew Wight on his journey north of the Cromarty Firth in 1781; improvement and innovation in 1700s farming; feeding oxen and horse; ‘a man of enterprising and comprehensive genius’; bere and barley.

In ‘Great quantities of aquavitae‘, the farmer-traveller Andrew Wight commented in 1781 on the denizens of Ferintosh, on the Black Isle, who “utterly neglecting their land, which is in a worse state than for many miles around” preferred to spend their time distilling bere (barley) malt than tending soil and growing crops.

Among places supplying grain to the Ferintosh whisky trade in the 1780s was (he reported) the farmland of Foulis (also spelled Fowlis), on the opposite, northern, side of the Cromarty Firth. Mr Wight rode his horse the long way round, but now Foulis is only a few minutes drive from Ferintosh over the bridge.

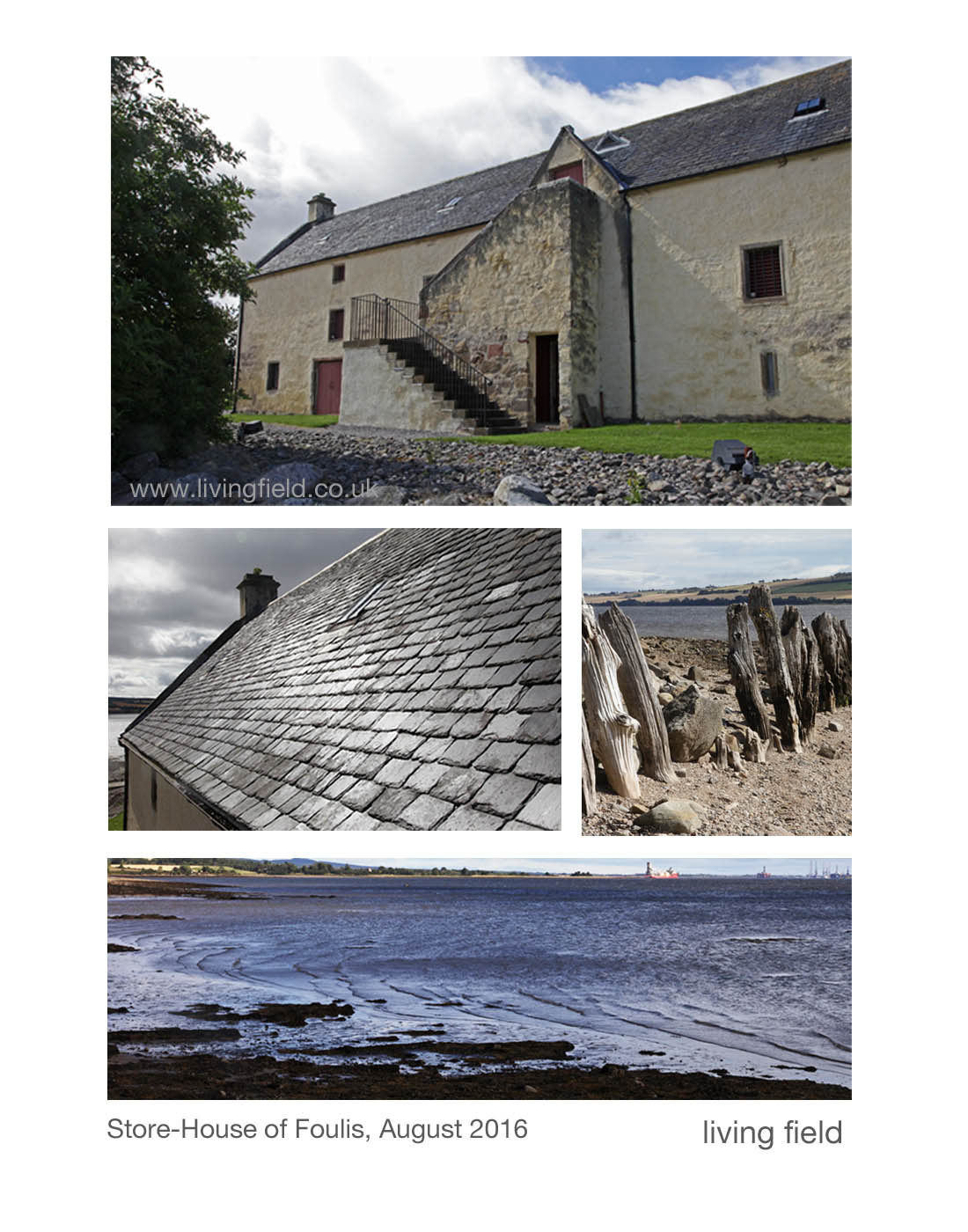

The Store-House of Foulis

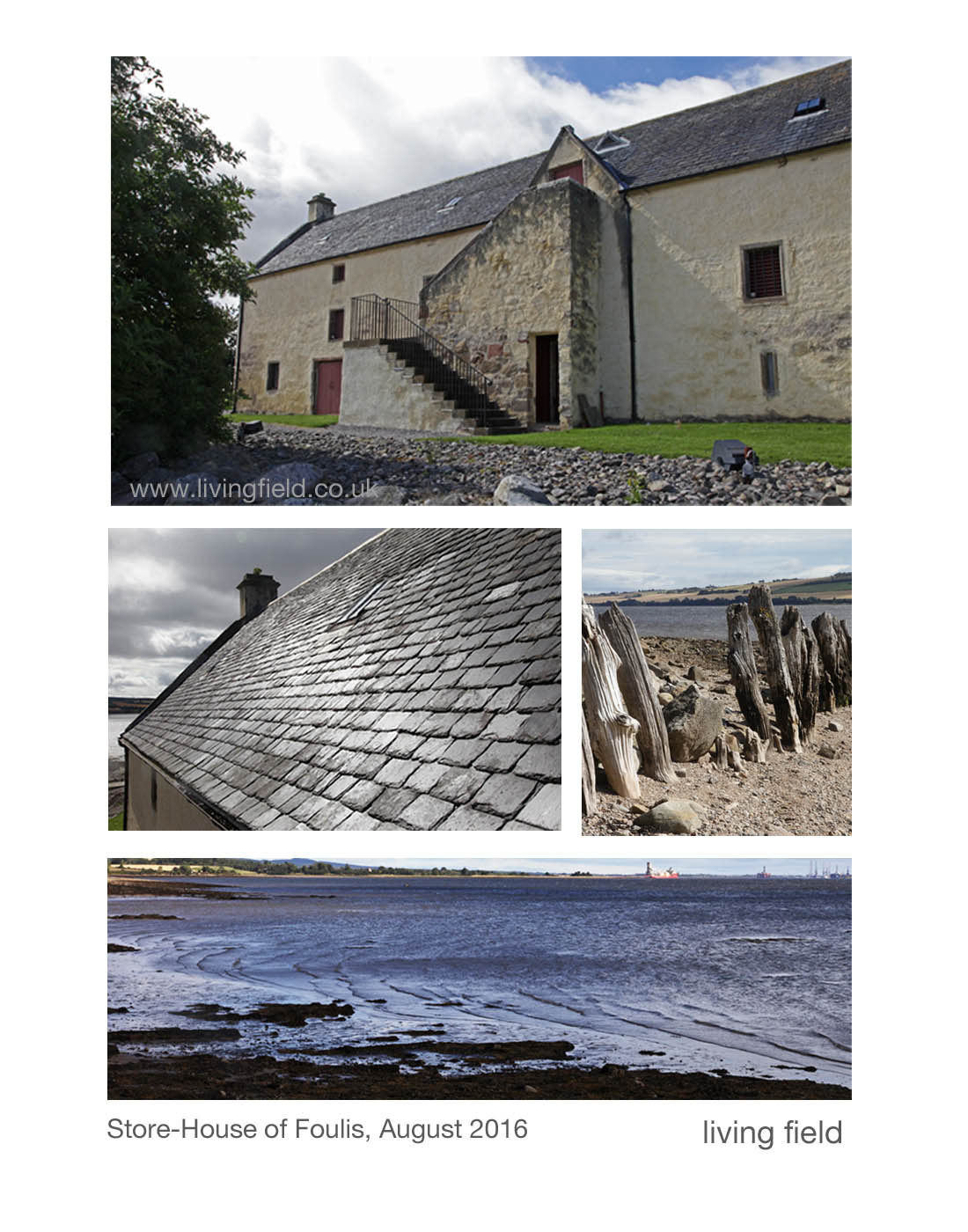

Andrew Wight did not write about the girnal or store-house at Foulis Ferry Point. It was built 1740, that is 40 years before he passed by on his journey north from Inverness (and that’s about 275 years before now). It was built to store grain before it was shipped off to market or paid to people in kind for work or favours.

The grain was grown by the estate or paid as rent by the tenants of the estate. They would grow grain on a farm or allotment and pay some to the landowner. Beaton (1986) reports accounts that the total barley received at the Store-House of Foulis in 1784 came to to 169 bolls two firlots. Example of payments ranged from 98 bolls one firlot from the tenant of Mains of Foulis to two bolls from a slater.

The Store-House of Foulis (map reference NH 599636) today has been well restored, with its fine slate roof and well harled walls (images above). Though sometimes called Foulis Ferry Point, the ferry ceased to operate in the 1930s. New buildings have grown around the site housing a visitor centre, restaurant and shops.

There area is rich in these store-houses or girnals as they were called, along the Cromarty Firth and up to Portmahomak. Beaton (1986) gives a map of locations.

Andrew Wight’s comments on the area

Mr Wight (IV.I p 241 onwards) writes about the crops, the farm animals, the owners, the improvers, the tenants and the peasants. Here are some excerpts from his journey along the north side of the Cromarty Firth from Fowlis eastward.

Of Fowlis (Page 233), he regales against the old practices – “having a baulk between every ridge, upon which were heaped the stones removed from the ridges; the soil was taken off every third ridge, in order to ameliorate the two adjacent ridges; and the crops alternately oats and bere; and to this bad practice was added the worst ploughing that can be conceived.” But after the land was improved by the then owner, he reports (page 235) a wheat yield of ten bolls per acre.

And on the same estate, Robert Hall, the farm manager of Fowlis ‘introduced a crop, rare in Scotland and an absolute novelty in the north, which is carrot. (…..) The farm-horses are fed on carrots instead of corn; and they are always in good condition.”

I rejoice to see six yoke of oxen

At Novar he remarks on the poor inherent quality of the soil, which is more than compensated by the desire of the estate to effect improvement to a degree that today would be thought of as ecological engineering.

He notes “Oxen only are employed both in cart and plough. I rejoiced to see six yoke of oxen in six carts, pulling along great loads of stones, perfectly tractable and obedient to the driver. They are all in fine order, and full of spirit. They begin labour at five in the morning, and continue till nine. They are then put upon good pasture, or fed with cut clover, till two; when a bell is wrung, and all are ready in an instant for labouring till six in the afternoon.’

At Invergordon, he comments on seven crops: “wheat on this strong land was very good; barley after turnip excellent; beans and peas are never neglected in the rotation; oats in their turn make a fine crop; the old pasture grass excels.”

Agriculture, manufactures and commerce, the pillars that support the nation

Several pages are devoted to the contribution of George Ross of Cromarty, MP a man of “enterprising and comprehensive genius”. He started a hemp manufacturing company employing many people and exporting coarse cloth to London and then a brewery for strong ale and porter, much of it “exported to Inverness and other places by sea-carriage”.

On Ross’s agriculture: “it is wonderful to see barren heath converted into fertile cornfields; clover and other grasses rising luxuriantly, where formerly not a blade of grass was to be seen; horse-hoed turnip, and potatoes, growing on land lately a bog; ….. hay, not known here formerly, is now the ordinary food of horses and cows”. He also cures and exports pork: “… he carried me to a very large inclosure of red clover, where there were 200 hogs of the great Hampshire kind feeding luxuriously.”

Ross works on a plan for improving the harbour and entertains “sanguine hopes that government will one day establish a dry dock near the harbour for repairing ships of war in their northern expeditions.”

Ed: Writing in 1810 after Ross’s death, Mackenzie (1810) states that the hemp trade was “now in a flourishing state. From (the year beginning) 5 January 1807, there were imported 185 tons of hemp; and about 10,000 piece of bagging were sent to London”. Ross was not so far off in his hopes for ship repair – Mackenzie refers to a ship being built there in 1810, and today there are deep anchorage and rig maintenance.

Eight fields, eight crops in sequence

Later on page 257, Wight comments on Mr Forsyth of Cromarty who manages a small farm divided into eight fields, and cropped as follows: “First potatoes, horse and hand hoed, with dung; second, barley; third, clover; fourth, wheat; fifth, peas; sixth, oats or barley, with grass seeds; seventh, hay; eighth pasture. … in this way ‘kept in excellent order, with the advantage of dung from the village”.

Throughout his journeys, Andrew Wight speaks his mind, always ready to praise good farming and condemn poor practice. (You can sense these journeys are more than a job.) And while he accepts the social divides of the time – he was commissioned by the wealthy – notably between the landed gentry and their peasants, he condemns those of the former who ignore, ill treat or exploit and praises those who support and encourage the people to improve their lot by agriculture, manufactures and commerce.

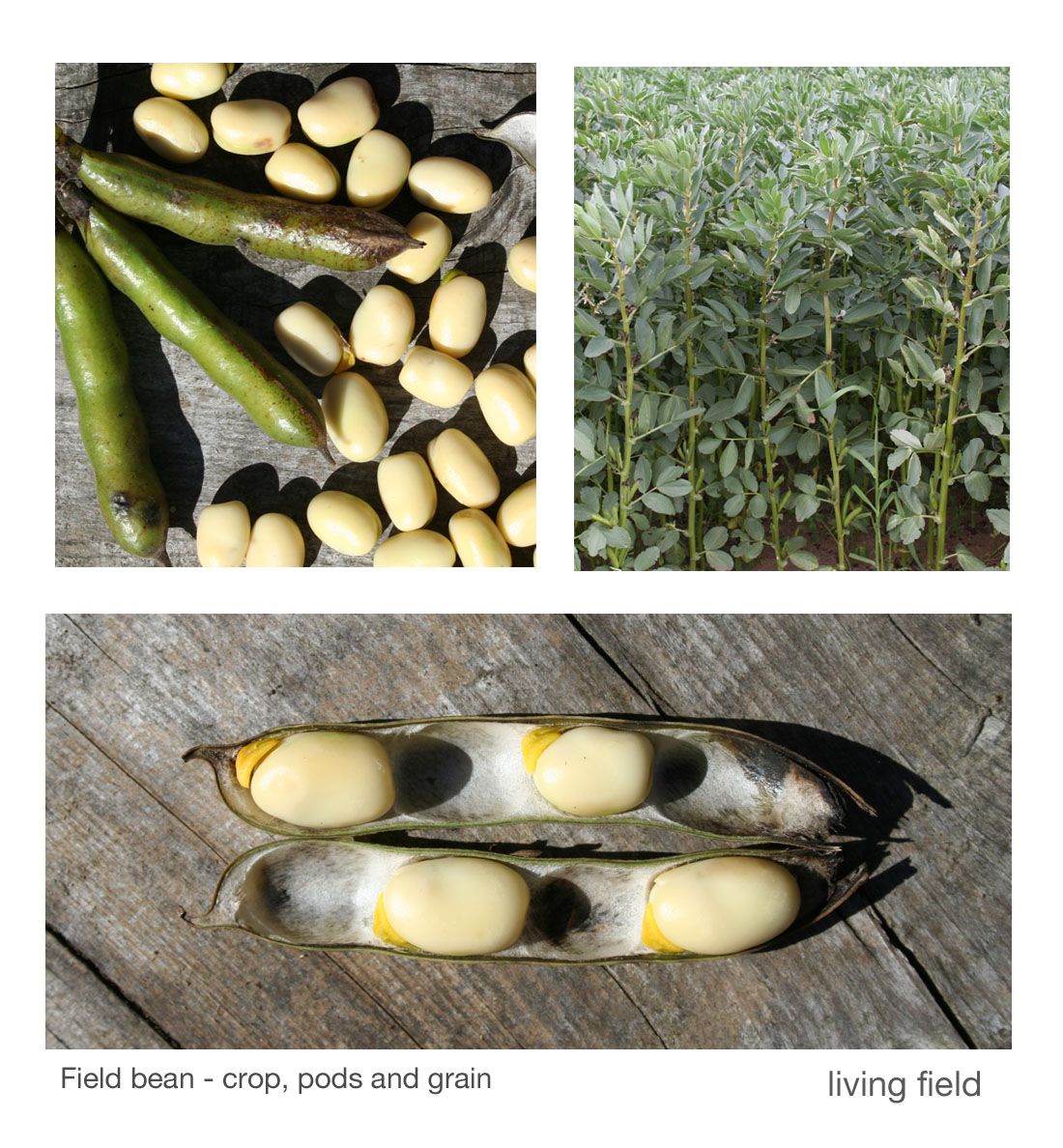

Other points to note are that legume crops (fixing nitrogen from the air) were common in crop rotations and that bere and barley are both mentioned but no clear distinction is made between them (see link to the Bere line below).

Sources

Beaton, E. (1986) Late seventeenth and eighteenth century estate girnals in Easter-Ross and South-east Sutherland’, In: Baldwin, J R, Firthlands of Ross and Sutherland. Edinburgh, pages 133-152. Available online: http://ssns.org.uk/resources/Documents/Books/Ross_1986/09_Beaton_Ross_1986_pp_133-152.pdf

Mackenzie, G S. 1810. General view of agriculture of the counties of Ross and Cromarty. London: Phillips.

Wight, A. 1778-1784. Present State of Husbandry in Scotland. Exracted from Reports made to the Commissioners of the Annexed Estates, and published by their authority. Edinburgh: William Creesh. Vol IV part I. (See Great Quantities of aquavitae for further reference and web links).

More on the Foulis girnal

Canmore web site. Foulis Ferry, Granary. https://canmore.org.uk/site/12905/foulis-ferry-granary Notes on history with references.

Am Baile web site: Foulis Ferry http://www.ambaile.org.uk/detail/en/20423/1/EN20423-foulis-ferry-near-evanton.htm

Images

Those in the upper set were taken of the Foulis Store-house and its surrounds on a visit in August 2016.

There were no ‘yoke of oxen’ around Foulis and Novar in 2016, so the Living Field acknowledges with thanks use of photographs from Burma (Myanmar) by gk-images, taken February 2014 (permission granted by the handler to take the photographs). The quotes below the images come from Wight’s text of 1784, and apply well to this magnificent animal).

Links to posts on this site

More from Andrew Wight on his travels in this region: Great quantities of Aquavitae and Great quantities of Aquavitae II.

The distinction between barley and bere: The bere line – rhymes with hairline and Landrace 1 – bere.

Maps of potato. legumes and vegetables in the region in the twenty-tens (and the relevance of this land over the last 2000 years?): Can we grow more vegetables?

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk