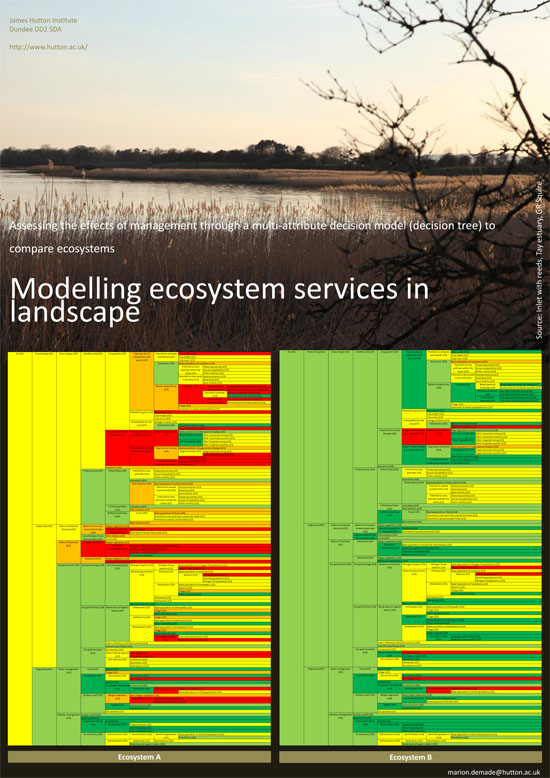

Tay Estuary Forum’s Annual Conference, this year on Sustainable Coasts, is held in Dundee on 23 April 2015. The small poster above draws attention to work showing the way different forms of land management may affect the estuary (Marion Demade, James Hutton Institute)

Author: gs

Feeding the Romans

Thoughts on a visit to the exhibition Roman Empire – Power and People McManus Dundee, on 14 March 2015.

This fine, informative display gave evidence of the Roman presence north of the Antonine Wall (between Forth and Clyde) around 2000 years ago. They set up marching camps and lines of communication, patrolled a long and complicated frontier, built great fortresses, then retreated. Yet few things remain to tell of their everyday life.

One was scale armour, known as lorica squamata [1], fragments found at the site of the fort at Carpow, near the junction of the rivers Tay and Earn in Perthshire. These small samples, linen cloth as backing, sown with 1-2 cm wide sheet-bronze scales, are stated to be the best preserved of this type of army gear in north-west Roman europe. They are rare intact because the linen cloth usually rots and disappears. Someone might have worn this armour to help protect them from a thrown stone or spear or a body blow from wood or metal. It is not known whether the fibre plant flax Linum usitatissimum used to make the linen was grown locally or even whether the cloth was made here [2]. There was a trade in linen throughout the empire.

Another was an amphora (a clay pot), reconstructed from pieces found at Carlungie, Angus, lying in one of the dwellings adjoining an earth-house or souterrain, used as an underground storage chamber. Amphora such as this were used to move wine, oil and other essentials round the empire. A note by the exhibit told the amphora was from Gaul (France) and contained French wine. Who brought it here is not known, but you can imagine the party.

Forts and fortresses along the northern frontier

These exhibits were some of the few fragments remaining in this area from the massive resourcing of the empire’s northern frontier. The Romans made Britain a province in 43 AD and by the 70s AD had established fortified lines and supply routes through (what are now) Perthshire, Angus, Aberdeenshire and Moray. They patrolled well north of the Antonine Wall, which itself is more than an hour’s car-drive north of Hadrian’s Wall in northern England.

They built and manned forts close to transport routes by land and water from the south and east, as at Carpow, and camps and signal towers along the Gask line that ran north of Stirling and continued north east along fertile Strathmore as far as the east coast near Stracathro, and from there, dog-legging north and north west across Aberdeenshire to Moray. A long way to march. A long way from home.

Surprising is the size of some of the garrisons. The one at Carpow, close to the Tay estuary and not far from the North Sea, and thought to be occupied between 180 and 220, was designed to hold 2000-3000 people. The massive base at Inchtuthil – a legionary fortress – by the Tay river west of Meigle (image above), commanded the way north from Perth and was estimated from its dimensions and excavated buildings to house 20,000 to 50,000. A small town! To do its job today, it would need to be sited a few miles farther west to command the A9 and railway from Perth to Inverness.

Roman Inchtuthil existed only for a few years in the AD 80s before it was purposely abandoned. Even if not fully occupied, these garrisons must have held thousands to tens of thousands of people, many of whom were soldiers with big appetites.

How to feed thousands of soldiers

They all had to be fed. They would have brought and tended some of their own livestock and perhaps grown some crops and vegetables nearby, but the staple food would have been grain – wheat, barley or oat. (There was no maize, potato or turnips then.) Just think how many packets of porridge oats would be needed to feed all those men every morning [3], and that grain would have had to be transported over long distances from the south or else stolen or coerced as tribute, or tax, from local people.

The SCRAN entry states: “The Roman army was adept at self-sufficiency. At Inchtuthil the legionaries exploited local resources of wood, stone, gravel, and clay to build their fortress. They manufactured their own lime, bricks, and pottery on the spot. Food and other raw materials such as leather would have been obtained from the natives, probably in the form of tax. The massive granaries at Inchtuthil hint at the scale of such levies.” And these granaries, or grain stores, were big, as shown by the diagrams and aerial images made during archaeological digs (online references below).

The exhibition says that when the Romans came the area was populated by farming communities of native tribes, scattered and based around fortified hill tops. This was the late Iron Age, so agriculture would have been widespread, but even so it would have been very hard pressed to support tens of thousands of soldiers in addition to the existing people. Imagine working hard all year to grow crops and then when they were harvested, you had to give away a lot of the grain for the privilege of having the Romans living nearby. The invaders can’t have been popular and presumably that is why they had to build these lines of communication and massive fortresses.

In conclusion

The Romans did not stay long. They arrived (in what is now Scotland) in the 70s (AD), which is about one thousand nine hundred and fifty years ago, but they were gone in less than 150 years. Their leaving is said to be the result of things happening elsewhere in the empire. Rome was too stretched – but (you have to ask) – was it the midge!

The iron age skills of growing crops and tending stock continued to the present time. So did working hard all year and giving away the harvest to those wealthier or more powerful. The Romans had no monopoly on oppression. It became endemic to northern agriculture.

Notes

[1] Squamata is the scientific name now given to reptiles that have scaly skin, the lizards and snakes.

[2] Flax is one of the oldest fibres plants, grown in Britain for several thousand years, see the Living Field’s page on Fibres.

[3] A packet of porridge oats weighing one kilogram contains 25 servings. To make 1000 servings would take 40 packets, and 10,000 servings 400 packets; and that would be just for one breakfast.

Sources and references

Introduction including material for schools

BBC Primary History http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/primaryhistory/romans/romans_in_scotland/

SCRAN Trust: information on the fortress at Inchtuthil and on grain stores http://www.scran.ac.uk/packs/exhibitions/learning_materials/webs/56/Inch.htm http://www.scran.ac.uk/packs/exhibitions/learning_materials/webs/56/Garrison.htm#granary

See also links to SCRAN for Carpow and Gask Frontier from the above pages.

Books and articles

Jones, RH. 2012. Roman camps in Britain. Amberley Publishing, Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK. Available as ebook via Google Books.

Hoffmann, B. 2013.The Roman invasion of Britain – archaeology versus history. Pen and Sword Archaeology, Barnsley, UK.

Wolliscroft DJ, Hoffman B. 2006. Rome’s first frontier: the Flavian occupation of Northern Scotland. Tempus publishing.

Archaeological investigations and records (RCAHMS)

Carpow: http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/30081/details/carpow/

Inchtuthil: http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/28592/details/inchtuthil/

Contact

geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

Photographs on this page taken early April 2015.

Roman Empire at the McManus Dundee

On at the McManus Gallery & Museum until 10 May 2015, an exhibition of antiquities, from the British Museum and local collections. See the earthenware pot (amphora) found near an Angus earth-house, said to have held French wine, and the linen-backed, bronze scale armour from Carpow where Tay and Earn meet. Web link: Roman Empire: Power and People – a British Museum Tour.

Spring equinox

Descriptions at The Year. For a look at other quarter days and cross quarter days – XQ1, XQ2, summer solstice, XQ3, autumn equinox, XQ4, winter solstice.

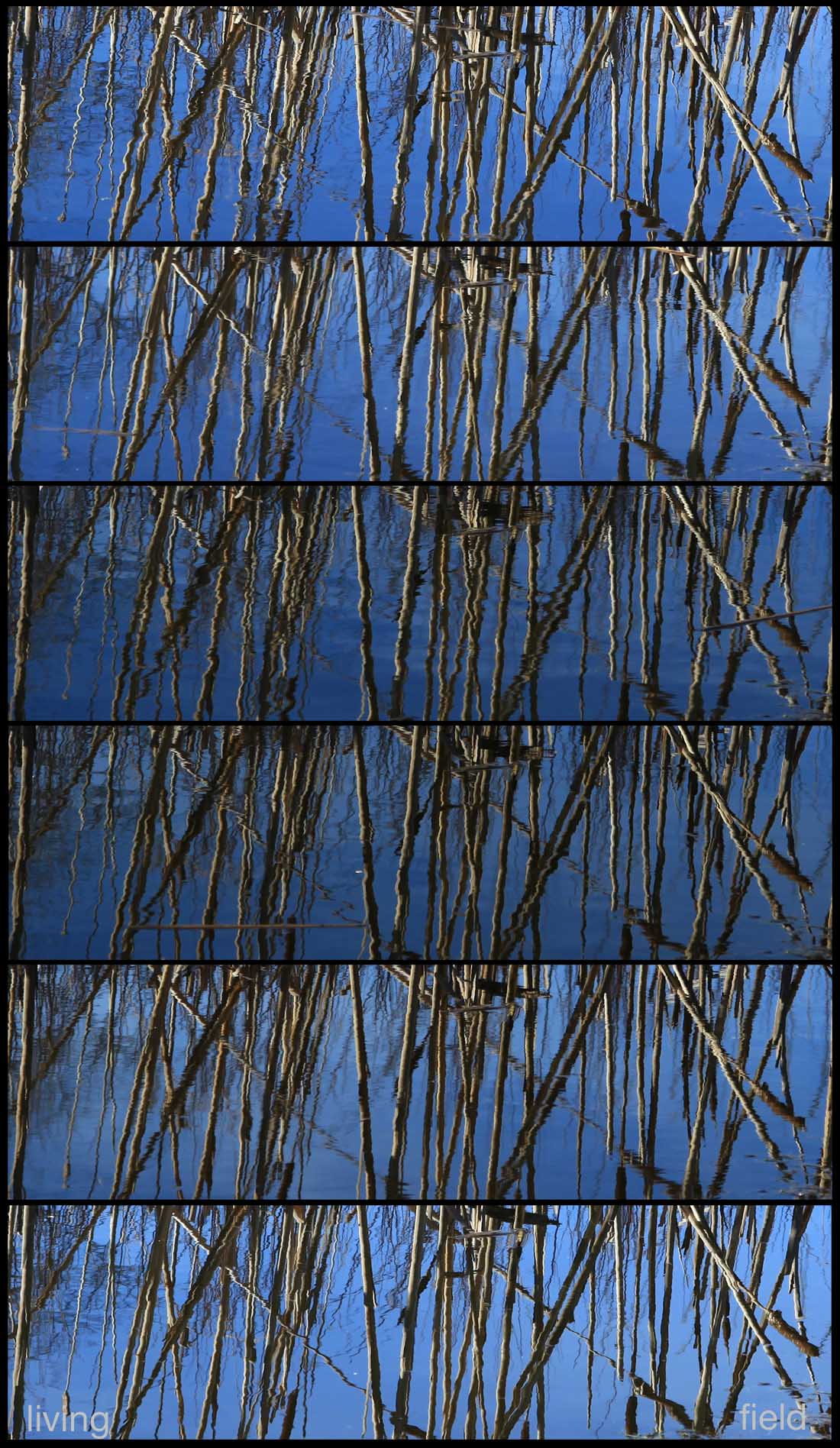

Reflection at the eclipse

How dark did it get at the solar eclipse of 20 March 2015? Not very dark. Here is the effect on bulrush stems reflected in a pond.

A few years ago, the Living Field and The Farm dug out and replanted an old mill pond at Balruddery. A few bulrush sets were planted on an island, where they took and thrived.

A few years later, the bulrush witnessed the solar eclipse on 20 March 2015. Their last year’s stems changed their reflection in the water as the light dimmed. Images above (top down) at 9.27, 9.29, 9.34, 9.35, 9.44, 9.51 (local time). A small effect at the earth’s surface. The birds still went about their business.

Hairy teacake

Of the photos taken at the Commonwealth Games fabulous opening night in 2014, the one icon of note missing from the collection was the Tunnock’s Teacake, the giant red and silver teacake replicas on legs, cavorting around the arena … not a single photo turned out.

That’s why we added the nearest thing – the marsh mallow. This plant was the source of marshmallow, the sticky confection used in cakes and now mostly replaced by other sweet sticky stuff, still called marshmallow. Yet it’s the hairy relatives of the marsh mallow that are more widely cultivated.

The marsh mallow Althea officinalis is a plant that lives in marshes and is one of the mallow family – that is why it came to be known as marsh mallow – but it also be grown in gardens and the Living Field has a few individuals in its Medicinals collection. The name officinalis indicates its use by the apothecary, in this case as a poultice, something to put on wounds. The plant has a darkness about it, the not-quite-white flowers never without a purplish tinge spreading up from the base, but its value to people over the ages is unquestioned.

This mallow family has many other useful plants in it, notably two that are valuable because of their fibres. Cotton and kapok are from warm countries and, unusual among the fibre plants, produce the fibrous material around their seeds, whereas most commercial fibre plants produce it in their stems. Cotton is now grown worldwide, over more area than any other fibre crop. Kapok is less familiar – the fibres used to be stuffed in pillows and furniture – but most kapok now sold is artificial, not made from the plant, but still called kapok.

The flowers of these plants are similar, the parts arranged in ‘fives’. (The specific name of kapok is Ceiba pentandra). But plants of the mallow family differ in many other aspects. Mallows in Britain are small or large perennial herbs, the marsh mallow reaching one and half to two metres; cotton can reach two to three metres; but the kapok is a big tree. An example is shown at the lower left of the images above, the red flowers colouring the outer branches of the tree, this one near Mandalay in Burma.

There is more on cotton and kapok on the living Field’s new Fibres pages, part of the 5000 years project.

Seeded oatcakes with bere meal

A recipe by for oatcakes made with wholemeal flour, rolled oats and bere meal, with a few extras.

Ingredients

90 g bere meal

50 g wholemeal flour

140 g porridge oats

1 teaspoon sugar, 8 twists of black pepper

1 large teaspoon salt

10 g butter or margarine (optional)

75 ml good oil like olive oil or Scottish rapeseed oil

Experiment with seeds like black onion seeds, sesame seeds, pumpkin seeds, golden linseed – just a handful.

Boiling water (variable)

What to do

Heat the oven to 160-170 degrees C and grease a large baking tray.

Add the dry ingredients to a bowl and mix well. Add the chopped butter and mix in by hand, as if you were making pastry. Add the oil and then mix together using a spoon or by hand.

Add boiling water, a small amount at a time until the mix comes together as a round ball. Flour the surface and roll out the dough to about 1 or 2 mm. Using a plastic or metal cutter, cut rounds and place them on a baking tray.

Bake for 20 minutes then turn over and bake for a further 10 minutes.

Cool the oatcakes and then eat with cheese or humous! Delicious! The above recipe makes about 30 oat cakes.

Comment

Beremeal has a distinctive flavour – along with haggis and whiskey, one of the distinctive tastes of northern cornland. You can replace some of the bere meal if you wish with medium pinhead oatmeal and follow the same instructions.

Alternatives

Try adding a handful of chopped fresh herbs like parsley or thyme instead of seeds.

Beremeal sourced from Barony Mills, Orkney.

Recipe by Grannie Kate

For more on bere barley and crop landraces Bere line – rhymes with hairline

Black sand through ice

XQ1 February

Descriptions at The Year. For a quick look at other quarter days and cross quarter days – spring equinox, XQ2, summer solstice, XQ3, autumn equinox, XQ4, winter solstice.

SoScotchBonnet

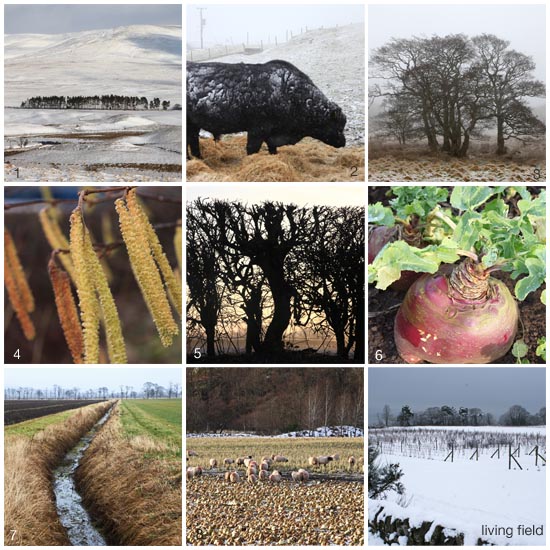

Indigenous crops; Scotch Bonnet; wool, woad and indigo; Tam o’Shanter, Burns supper; staple food of the north Atlantic seaboard; tatties, neeps, oat and barley; the grey cat!

In its undying search for the truly indigenous crop, the Living Field investigated the ‘Scotch Bonnet’, to find it was nothing local at all, but a hot little capsicum, now grown in the West Indies and other tropical places and used to give some spicy heat to food.

Why then is it called the Scotch Bonnet? It seems because it looks like one. Unlike many varieties of the chillies, this one bulges and sometimes flops when it leaves the stem: to some, with imagination, it resembles a Scotch Bonnet, on a head.

The Scotch Bonnet

Now the Living Field is well disposed to the headgear named Scotch Bonnet, originally made of local fibre, usually wool, and dyed blue with woad Isatis tinctoria, which was once grown as a crop in these islands, or with the deeper indigo Indigofera tinctoria, which is imported and replaced woad. Such skill and craft go into making this one little hat: you have to rear the sheep and shear them, then wash, spin and weave the fibre, grow and harvest the woad or indigo, extract the dyestuff, dye the cloth, then form it into a shape that would fit on a head – and it was all done before electricity.

But we see the Scotch Bonnet (headgear) is also called the Tam o’Shanter, and this is, it seems, because Tam in the poem by Burns wears a blue bonnet – it’s mentioned only once, but there it is – ‘Tam’s blue bonnet’.

Tam o’Shanter

Now these three words do not define what sort of bonnet it is, yet those who have depicted the bonnet in drawings and paintings of the epic give it the character and shape of a Scotch Bonnet, and those such as Alexander Goudie (1933-2004) who have painted in colour give it the colour blue – woad-blue or indigo-blue.

In Goudie’s fabulous paintings, the blue bonnet is there in almost every picture. It grows in significance. Even when chased by Cutty Sark and the other infernals, the blue bonnet stays on. Even when, with diminishing sark, she grabs Maggie’s (Tam’s mare’s) tail, pulls it and leaves just a stump of hair … the bonnet stays on. Considering the state of Tam, and the number and aggression of the infernals .. you wonder how the man and mare escaped? Was there something in these blue-bearing plants that somehow made Tam and his mare go faster or the infernals slower. Doesn’t matter, because if they had caught him, there would be no recitations of the poem and much less fun at Burns Night.

Burns Night

The poem Tam o’Shanter is very much associated with the festivities of the Burns Supper, and through the medium of the Supper, visitors can sample some of the great staple food and drink of the north Atlantic seaboard – oat, swede, potato and barley. Together, and with offal, including lungs, and other fleshly stuff from sheep, they make the traditional meal of haggis, neeps and tatties, the barley going not so much into the haggis as into the dram for those who partake (though, on the Night, the dram can sometimes … well … go into the haggis).

Would Burns have known the main crops that now form his Supper – he was a farmer for a few years? Sheep of course he would have known. Of the three main vegetable constituents, only oat has been here for a long time and that for thousands of years. He would have known oat. The neeps, usually swede rather than the (white) turnip, and tatties (potato) are relative newcomers, arriving perhaps a few decades before Burns was born. Burns probably knew about swede and potato but might not have grown them. Barley is older than oat here and he would have known barley and certainly known its products.

So while Burns (1759-1796) is now celebrated around the world, the world reciprocated before he was born by offering the vegetable constituents of his commemorative supper – oat and barley from west Asia, swede from (probably, though it’s not certain) east Europe or west Asia and potato from Central America. What a generous world!

Sources at the bottom of the page give links to his poems and song and to the Scots Dictionary. The image of haggis, neeps and tatties (above) was taken at a Burns ‘lunch’ at the Hutton staff restaurant. For those who want to know more about the crops, below is something more on swede, potato, oat and barley.

The crops

Tatties

The tatties’ tale is well told elsewhere. Briefly, potato Solanum tuberosum arrived in Britain from the other side of the Atlantic in the late 1500s, but gained little interest other than a garden curiosity until …..

“To Thomas Prentice, a common day-labourer, who lived near Kilsyth, is the honour due of bringing this useful esculent into general notice in Scotland [so wrote Lawson and Son in 1836 only 40 years after Burns’ death … and read on … ] He procured, in 1728, some “sets” from Lancashire, and bestowed considerable care in their propagation; and as their value became known, they were eagerly sought after by his immediate neighbours. By continuing the cultivation he, in a few years, saved upwards of £200, with which he purchased a small annuity, on which he lived independently to an old age, dying at Edinburgh in the year 1792.”

So Thomas got his tattie tubers from Lancashire well before Burns was born and he died only a few years before Burns did. Burns was probably familiar with the potato, but only just. His parents’ generation probably did not know it and his grandparents’ would not have known it. Yet what an explosion of genetic resources there was after that, because little over a hundred years later there were 175 recognised types of potato known to Lawson and Son (1836, 1850) and today there are great collections of genetic resources such as the one at the Hutton Institute.

Neeps

In their list of 1852, Lawson and Son, seedsmen from Edinburgh, write “in modern times the turnip seems to have been re-introduced to this country from Flanders about two-hundred years ago” which is the 1650s or thereabouts, but they also state that the time of introduction and the degree of cultivation of the swede or Swedish turnip is less certain though probably later (let’s approximate to around 1700). By Burns’ time the turnip had become a commercial farm crop in some areas of Scotland. Today the turnip has the botanical name Brassica rapa and the swede Brassica napus.

Both types of turnip were used to feed horses and cattle, but also people. The swede, the same species as oilseed rape, has leaf that is less coarse and hairy than the turnip, bluey-green rather than bright green and generally a yellow-orange flesh rather than white, which colour remains when cooked and mashed. So the neeps that are eaten these days with haggis and tatties are mostly swedes. An excellent vegetable, rich, smooth and distinctive to the taste, one of the very finest of the cabbages.

The corn

Oat Avena sativa and barley Hordeum vulgare had been the staple cereals of the north atlantic seaboard for a very long time. Charred grain of barley has been found in the earliest farming settlements. Their relative popularity has risen and fallen but in Burns’ time, oat was by far the most common, and it is the meal ground from oat grains that binds the animal constituents of the haggis. Today it’s the other way round, barley is the commoner crop, though oat is the one still used in haggis. More on oat and barley can be found on this site at Garden/Cereals and in the series of articles on landraces, e.g. The bere line – rhymes with hairline.

The grey cat?

She says “Arrived, invited, for a SoSCOtchBOnnet photoshoot posing in nothing but a Scotch Bonnet – and what a bonnet! Fine wool, indigo-dyed, cost me the earth … credit card maxed out … but the editor says ‘no nudity on the Living Field web site’ and I had to keep my fur on … no fun in that. Name’s Meggie by the way, like Tam’s horse Maggie but with an ‘e’. I do photoshoots. Call me.”

Sources

Burns poetry. Best get a book of it – there are several – and read it by a fireside on a winter’s night or in a field of corn and poppies in midsummer.

Burns is accessible online, e.g. http://www.robertburns.org and http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/robertburns/biography.shtml

Tam o’Shanter, a tale by Robert Burns, illustrated by Alexander Goudie. 2011. Berlinn, Edinburgh. More on the artist at http://www.alexandergoudie.org.uk at which – check under ‘paintings’ and ‘Tam o’Shanter’.

A Scot’s dictionary is handy if you are not familiar, e.g. The Concise Scots Dictionary (The Scots language in one volume from the first records to the present day). Editor in Chief: Mairi Robinson, 1985. Aberdeen University Press.

Online Scots http://www.scots-online.org and http://www.dsl.ac.uk

Lawson and Son’s exhibitions and lists of 1836 and 1852 are described on this site at Bere in Lawsons’ Synopsis 1852