The Living Field is pleased to see Tracey Dixon’s image of the Garden’s emmer wheat Triticum dicoccum take prominence on CECHR’s poster.

Author: gs

Kidney Vetch and the small blue

The kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria was noted in a recent post about nitrogen-fixers living by the shore on the east coast of Angus. But the kidney vetch has wider acclaim as host of the rare Small Blue butterfly Cupido minimus.

The small blue lays its eggs in the flowering heads of kidney vetch. The hatched larvae then eat the flowers and the developing seed.

However, the range of the butterfly in the north east has decreased in recent years and attempts are being made to record its occurrence. For more on the small blue and current surveys in Scotland –

- Butterfly conservation – small blue

- North East Biodiversity – small blue butterfly project

- East Scotland butterflies – small blue survey

In the latter can be found people to contact if you want to take part in surveys or to report sight of the butterfly.

Kidney vetch

The kidney vetch is one of the nitrogen-fixing legumes that occur in nitrogen-poor, dry and unshaded environments around the coast of eastern Scotland.

Yet it was once considered as a sown forage – a constituent of vegetation managed for stock-feeding. Lawson and Son (1852) write that it ‘does not yield much produce, but is eaten with avidity by horses, sheep and cattle, and also by hares and rabbits, and might therefore be introduced into mixtures for very dry soils’.

In the Garden

The Living Field garden grows kidney vetch in its medicinals collection and in the raised beds that have housed a legume collection over the past few years (images below). It grows well, forming luxuriant clumps up to 30 cm in height, taller than on the coast. The flowers are usually more yellow, less red than on the wild plants.

It flowers and seeds profusely in the garden. Some plants die in the winter, but in the last two years it has regenerated freely from its own dropped seed.

The flower heads

The round ‘wooly’ heads may be confusing at first sight, but each ball consists of usually three separate heads each holding many individual flowers. The three heads do not all flower at the same time.

In the image at the top of the page, the head to the lower right is the latest to flower – some flowers are still in bud while others have the fresh yellow petals emerging from the red calyx tube (which previously enclosed the bud). The head to the left has a mix of new and withered flowers. The largest one, at the top middle and right, has finished flowering: all petals are withered orange, the calyx tubes have turned purple and the hairs have expanded into a whitish mass, protecting the seeds that will form deep in the tubes.

Reference

Lawson and Son. 1852. Synopsis of the vegetable products of Scotland. Authors’ private press, Edinburgh.

Fixers 1 Coastal legumes

First in a series on nitrogen fixing legume plants.

Legumes are a group of plants that ‘fix’ nitrogen gas from the air to make proteins that are essential for growth and survival. When legume tissue dies, the nitrogen (N) is returned to the soil.

Legumes have many uses to people as food, medicinals and dyes. They also support insects that in turn carry out ecological functions such as scavenging and pollination.

Here we begin a short series on wild N-fixers. First are those that live by the eastern shores of Angus.

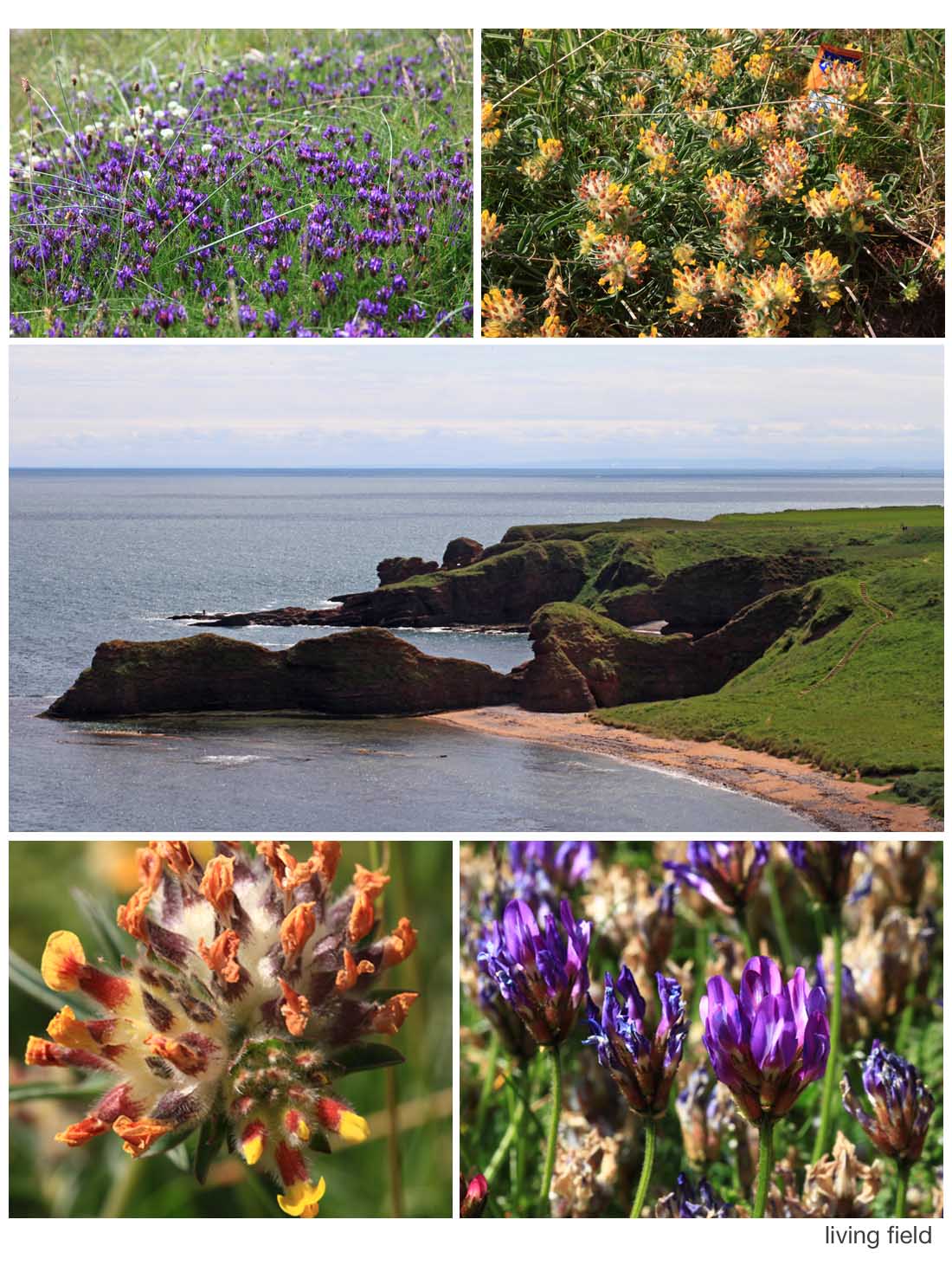

The east coast of Angus (middle image) is rich in wild legumes. Those shown here live just above the beach or on top of the cliffs, where the vegetation is short and there are no bigger plants to out-shade them. Top left is a patch of purple milk-vetch Astragalus danicus and white clover Trifolium repens behind, top right kidney vetch Anthyllis vulneraria with litter, and ( bottom) flowering heads of kidney vetch (left) and purple milk vetch.

Nearby were patches of meadow vetchling Lathyrus pratensis, bird’s-foot-trefoils Lotus species, and on the cliff-tops bush vetch Vicia septum, gorse or whin Ulex europaeus, broom Cytisus scoparius and the introduced laburnum Laburnum anagyroides.

One reason for the presence of legumes here is an unfarmed habitat, low in nitrogen. Fixation by the legumes is one of the main routes by which the plants and soils get their essential nitrogen.

Most of these wild legumes have been tried over the last few thousand years as crops or forages. Some such as kidney vetch have been well-know medicinals (a vulnerary is a herb for treating wounds). Few have remained useful to agriculture, perhaps the best known being white clover, still cultivated today to enrich grass fields with fixed nitrogen.

Legumes are of the pea family Fabaceae, previous known as Leguminosae.

Related on this site:

- Kidney vetch and the small blue

- Fixers 2 – restharrow

- Fixers 3 – crimson clover

Contact: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk

Bere bannocks

This recipe is an adaptation from the booklet ‘Barony Mills – Bere Meal Recipes’ from Birsay, Orkney.

Ingredients

60 g self-raising flour

40 g rolled oats

2 teaspoons bicarbonate of soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

250 ml milk

What to do

Mix all the dry ingredients together then add enough milk to make a soft dough. Turn out onto a board coated with beremeal/oat. Flatten by hand until about 1 cm thick, then make rounds using a pastry cutter (7 cm). Bake in the centre of the oven at 170/180 degrees C for about 10 minutes, then turn the bannocks and bake for 5 minutes. Alternatively, bake on a dry griddle or pan on the top of the cooker for about 5 minutes each side. This makes a batch of about 8 bannocks. Alternatively, shape into a large round, mark out 8 segments and bake for about the same time.

Notes

The original recipe was used by the Creel Restaurant, St Margaret’s Hope. In addition to the beremeal, it used 100 g plain flour and no rolled oats. I have substituted this with 60 g self raising flour which gives a bit more ‘lift’ to the product. The rolled oats also seems to make the bannocks lighter, almost a cross between bread and a scone!

The crucial thing in baking bannocks is to get the proportions right – proportions of the dry constituents with the right amount of raising agent, in this case baking powder.

Barony Mills is Orkney’s only remaining working mill – and a water-powered one at that. It produces traditional Orcadian beremeal, a speciality flour with a nutty brown colour and a distinctive flavour, which has been used in this recipe.

Recipe by Granny Kate

Links on this site

Seeded oatcakes with bere meal

The bere line – further links and pages on the history and uses of bere barley

Landrace 1 – bere – for information on the Orkney bere landrace

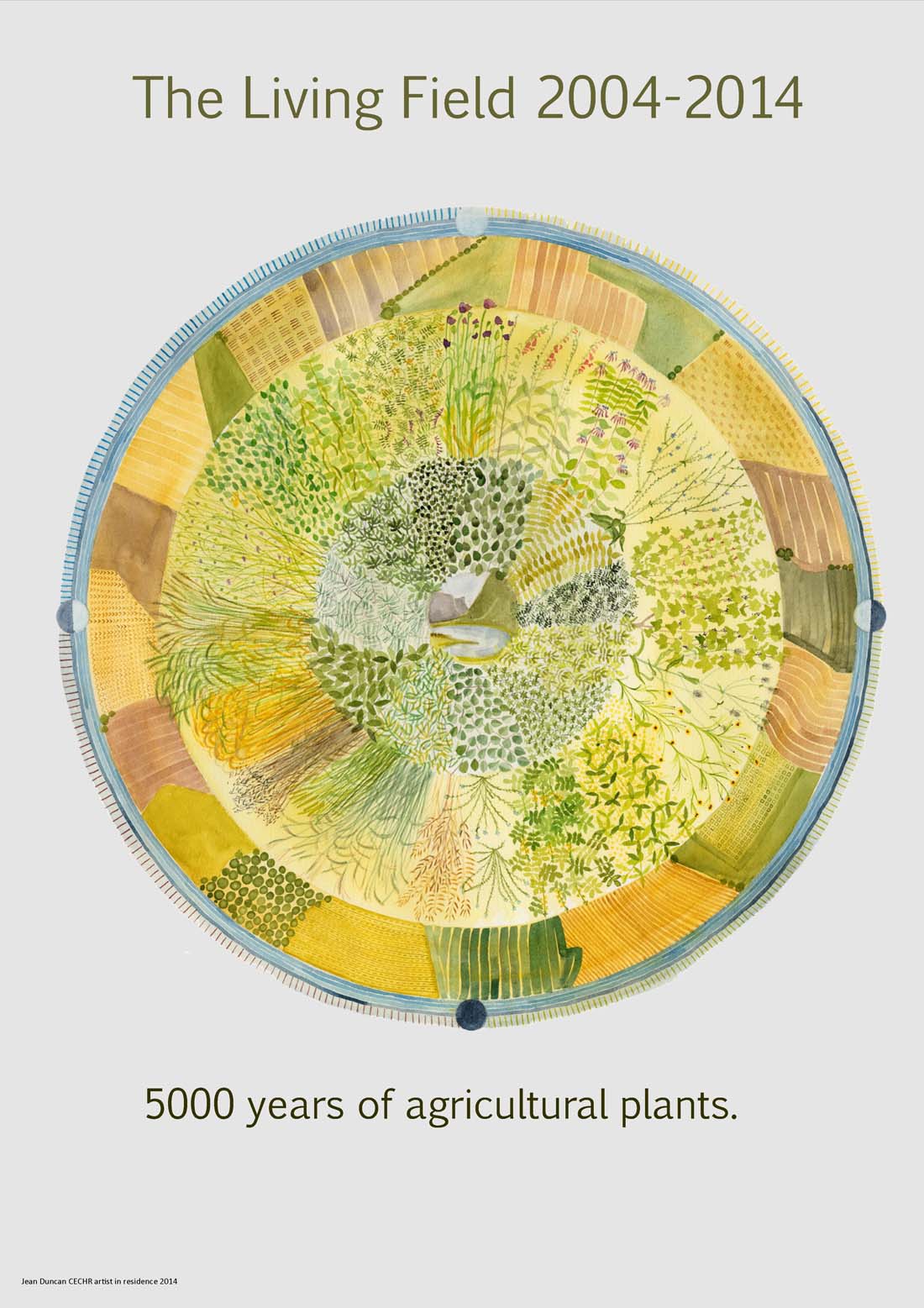

5000 years

New wood sculpture

Dave Roberts very kindly donated to the Garden this chain saw sculpture of a dragonfly. The sculpture was carefully installed in the meadow on 28 May 2015.

Images above were taken late evening on 28 May, looking north. And then squally showers … and a rainbow.

His Facebook page at Dervish Carving shows some photographs of the work in progress.

Images by Squire / Living Field

Corn grain bread bannocks

A Living Field exhibit at Open Farm Sunday this year on 7 June 2015 10 am to 4 pm at the James Hutton Institute, Invergowrie, Dundee.

Plant to plate: see and touch corn (cereal) plants, ancient and modern; have a go at threshing; try hand-grinding grain; see bread, biscuits and bannocks made from bere (an old Scottish barley landrace), rye, spelt and oat.

Images above show (top) ripening ‘ears’ of emmer wheat grown in the Living Field garden, a bag of oat grain and the Living Field’s rotary quern for grinding grain into meal

Contact: gillian.banks@hutton.ac.uk.

175 years ago today

As if to presage our various web-entries on natural fibres, oils, medicinals and culinary spices, the notes below, from the Advertiser, of 1 May 1840, reproduced in the book ‘The Trade and Shipping of Dundee 1780-1850 by Jackson & Kinnear [1], confirm Dundee’s desire to trade globally in natural products in the mid-1800s.

[Images to be added]

Arrival of the Selma at Dundee

The time (1840) was transitional for Dundee and its hinterland. It was at the beginning of a phase of international trade that gave the area status as a port and manufacturing centre. Jackson & Kinnear relate that the barque Selma arrived on that day from Calcutta … the first with cargo directly for Dundee.

Selma contained, among other things, over 1000 bales of jute, many sacks of unseed [2] and linseed, 300 bags of sugar, more than 1100 bags of rice, coir fibre from coconut and almost 2000 whole coconuts, and teak planks and bamboo; also buffalo horns; spices and condiments – preserved and dry ginger, canisters of arrowroot, tea, black pepper, cloves, nutmegs, mustard seed, castor oil, chillies and cubebs [3]; hogsheads of wine; and then borax and camphor; samples of hemp Cannabis sativa, presumably for fibre. This is an amazingly varied cargo of plant, animal and mineral goods coming into Dundee, on one ship, 175 years ago.

Half-forgotten plants and natural products

Many items in the Selma’s cargo are still in common usage today, but others may be less familiar. Are you kitchen-cupboard-ready?

Arrowroot a starch from tuberous parts of the roots of some tropical species, e.g. cassava Manihot esculenta, used as a thickening agent in cooking and to make arrowroot biscuits – biscuits your granny gave you, proper, decent, thin, no chocolate, no sugar, could be dunked in tea without falling to bits and dropping in – just biscuits.

Castor oil (beavers love it) from the castor-oil plant Ricinus communis, among other things, used as a laxative: pinch the nose, open the mouth and in with the spoon! Castor oil has many legitimate medicinal and industrial uses, but its laxative, and thereby dehydrative, properties have been used as a means of systematic punishment and torture [4]. The seed-oil is extracted by complex methods; the seeds also contain the highly poisonous ricin.

Borax (not a superhero but) a white crystalline substance made from a salty deposit when lakes in some parts of the world such as Tibet evaporate. Borax is used as a mild disinfectant and cleaner. It was put on children and other humans to cure infections like athlete’s foot and dabbed on mouth ulcers (it stings!).

Camphor. A strongly aromatic extract from some tropical trees, also found in the plant rosemary. Went into mothballs, made old drawers smell funny. Camphorated oil got rubbed onto childrens’ skin to do it good.

Cubebs from Piper cubeba a bit like black pepper corns but with a short stalk (‘pepper with a tail’), mainly grown in Indonesia, and traded for many centuries in that region; employed as an aphrodisiac in Goa as reported by the traveller Linschoten in the 1580s (Q: how did these explorers and ethnobotanists get to know such things – did they experiment?), stimulant and antiseptic, and a tonic for ‘every disease that flesh is heir to’ [3] ….. and much more.

What were they like!

The question you have to ask is what Dundee folk were up to in those days 175 years ago, at least those few that could afford all these exotic imports. Hemp, cubebs, cloves, hogsheads of wine … the ingredients of wild days and nights, and then they came down to earth with borax, camphor, castor oil and coir shirts. And what about the buffalo horns – what were they used for?

Sources and notes

- Jackson G, Kinnear K. 1991 The trade and shipping of Dundee 1780-1850. Publication 31, Abertay Historical Society, Dundee. Scanned 2010 and available online http://www.abertay.org.uk. The list of commodities carried on the Selma is given at page 20 and Ch 3 note 32.

- Unseed – this had the Living Field in a stir. Even Burkhill’s 2400 pages did not list it [see note 3]. But thanks to an online note found from an internet entity named ‘cyberpedant’, we are reassured that the original was likely ‘Linseed’ and that when documents are scanned, the shape ‘Li’ is commonly read as ‘U’. Relief! Otherwise we’d be scanning the world for unseed seed and never finding it.

- Cubebs. Notes above taken from Burkhill IH, 1966, A Dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsular. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Malaysia (2400+ pages). On the aforesaid properties, Burkhill cites Jan Huyghen van Linschoten’s Historical Voyages, published in English 1610.

- Castor oil. The author Umberto Eco, in the Mysterious Flame of Queen Loanna (2004), relates in Ch 12 a story of a journalist in fascist Italy being forced to swallow a bottle of castor oil as punishment. But after the first two purgings, he regained enough presence of body and mind to bottle and seal the next expulsion of oil and faeces. The bottled contents, sealed from the atmosphere, were kept in hope that the fascist tide would turn, and when it did, the means were found to trace the original perpetrator and pour the 21-year-old vintage down his throat. A delicious passage!

Iceland

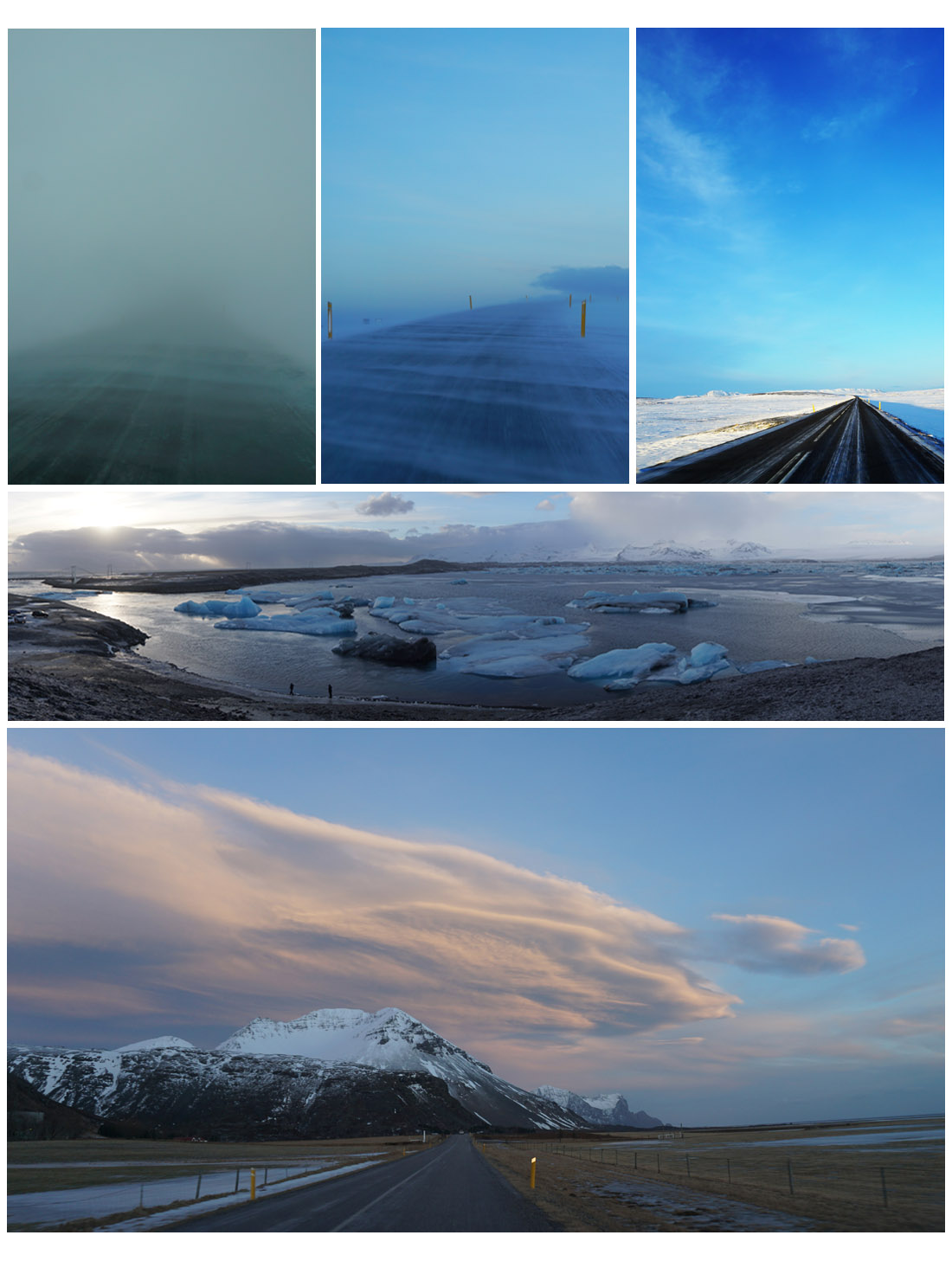

Kirstin Buchholz & Michael Munson (photographer) visited Iceland in February 2015. Here are some of their impressions and images of the places on the route.

Their visit took place during the Holuhraun volcanic eruption (click link for events in February 2015) which began on 31 August 2014. to the north of Vatnajökull glacier.

Kirsten writes: “When we started off in Reykjavik, it was chilly with 4°C and clear sky. When we reached the Golden Circle, it got colder, windier and we even had snow. Down south, it was about 0°C, windier and lots of broken icebergs from the glacier Vatnajökull in Jokulsarlon. The south and east coast of Iceland reminded us about Scotland’s west coast. The rocks, the maritime climate, the wind, the rain, the seagulls and the snow covered hills, apart from the black sand beach in Vik! …….. “

“The canyon Jokulsargljufur on our way north to Iceland was impressive – also the weather changed dramatically. The temperature dropped down to -10°C with snow, sleet, hail and rain and very high wind – sometimes all simultaneously! The cloud cover changed by the minute so the chances of seeing the Northern Lights were slim. There were loads of farms, cattle and horses around the south, east and north of Iceland. There are also reindeer, mostly on the east coast.”

Vatnajökull

The Vatnajökull glacier and its surrounds is a National Park, the largest in Europe, notable for its sub-glacial lakes and volcanos concealed under the ice cap. The last eruption was in 1996. It broke through the surface of the ice, emitting an ash cloud 10 km high. The subsequent spectacular release of meltwater caused great damage but increased the land area of the country by 7 square kilometres. There’s more on Vatnajökull at Iceland on the Web.

Mývatn

… the name of a lake in northern Iceland, which like Scotland was covered in ice during the last glaciation. The region experienced several major volcanic eruptions in recent millennia. One that happened 2300 years ago – that’s the middle of the Iron Age in Britain and the founding of Ancient Messene in Greece – led to the formation of the lake.

The area around the lake is still geothermally active, the images below showing smoke and fumes rising from small craters and holes in the ground.

Skógafoss and the southern agricultural plain

The farmland of Iceland experiences a form of the ‘northern cool summer’ effect in which the solar income is spread over the long days, encouraging crops and grass to produce a high output. The main farming activity is stock raising.

The waterfall, Skógafoss, is a major attraction of the southern region of Iceland. The fall is seen to the lower right of the top right image above. Note the red roofs in the left centre of that image – they are seen again at the right centre of the image to the left, which then shows the river flowing from the waterfall through pasture continuing down to the sea in the distance. The lower image taken from Skógafoss shows the strip of coastal grazing land, between hills and sea.

Þingvellir

And we end with this scene in fading light from Þingvellir. The Þingvellir (or Thingvellir) National Park was designated by law in 1928 and protected as a national shrine.

A general assembly (parliament?) began here about 930 and continued until 1798.

Thingvellir is one of the partner sites in the Thing Project – a move to coordinate the documentation and history of viking or norse ‘assembly’ sites – Thing sites – in North West Europe. Partners in Britain include organisations and sites in Shetland, Orkney and Highland Region at Dingwall.

Notes, credits

All images copyright of Michael Munson and Kirsten Buchholz. Additional material by GS.

The Icelandic Met Office give a month-by-month account of the Holuhraun eruption at en.vedur.is. The eruption was declared to have ended in early March 2015.

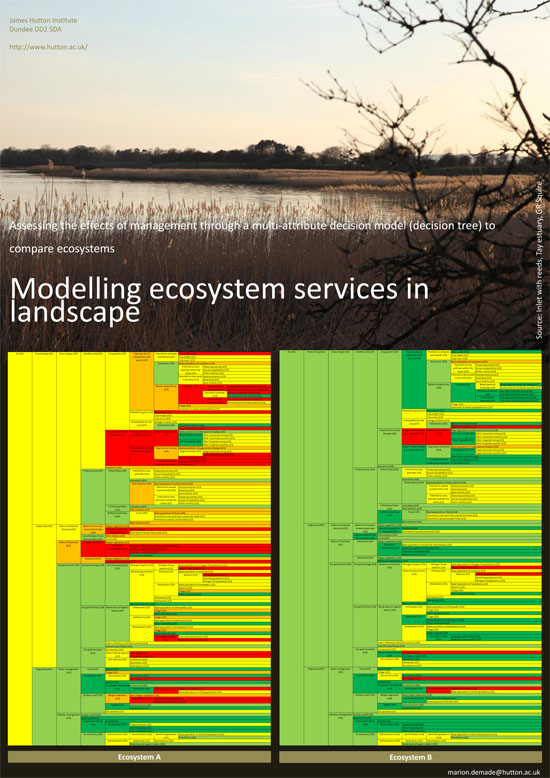

Sustainable coasts

Tay Estuary Forum’s Annual Conference, this year on Sustainable Coasts, is held in Dundee on 23 April 2015. The small poster above draws attention to work showing the way different forms of land management may affect the estuary (Marion Demade, James Hutton Institute)